Bliss Symposium Award

Juan David Grisales, Master of Landscape Architecture candidate, 2019, Harvard Graduate School of Design; Master of Design Studies (Urbanism, Landscape, and Ecology) candidate, 2020, Harvard Graduate School of Design

Attending the “Military Landscapes” Garden and Landscape Studies Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks was an amazing opportunity that contributed both to my formation as a landscape architect, and my current goal of examining how the discipline might serve as a medium to generate physical and social integrations at multiple scales in places troubled by conflict and contested or fragmented territories where landscape architecture is not yet established as a profession.

The symposium’s great variety of topics and presenters exposed how war and conflict have always been present in society, producing tensions that manifest in the landscape in different forms. During my time at the conference, I was able to relate to many of the conditions discussed, which hearkened back to my life and practice in Colombia, a country where people have often lived in fear of the landscape because of a dark recent past of war and political conflict, so much so that being outside and being in nature have sometimes been synonymous with being vulnerable and in danger.

The symposium was also a good opportunity to connect with great scholars, professors, and students from different parts of the world. Furthermore, being able to visit the gardens, the museum, the library, and other facilities at Dumbarton Oaks was very enjoyable. I would like to thank Dumbarton Oaks for granting me the Bliss Symposium Award, allowing me to attend the “Military Landscapes” symposium, and I look forward to the possibility of coming back soon.

Ann H. Lynch, Master of Landscape Architecture candidate, 2019, Harvard Graduate School of Design

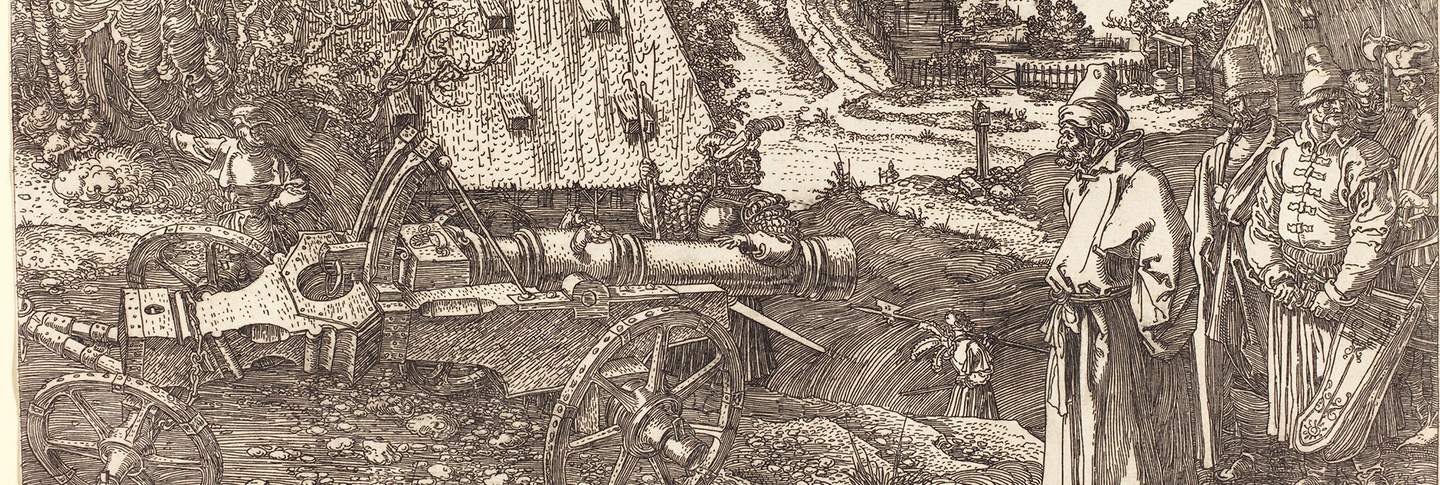

The questions foremost in my mind leading up to the Garden and Landscape Studies Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks centered largely around the role of the landscape architect in the monumentalization and memorialization of military conflict. After a stimulating two days, however, my very understanding of what defines a “military landscape” was critically (and necessarily) destabilized. Each speaker illustrated the ways in which military conflicts produce their own geographies, and the speakers’ examinations of military conflict from the middle ages to the present also collectively proved that there is scarcely a place on earth untouched by military conflict.

With this knowledge, the discipline of landscape architecture must reposition itself in relation to history. Today, the practice of landscape architecture presupposes a neutrality of spaces and sites of intervention. However, as poignantly elucidated by the symposium’s speakers, any site is inevitably endowed with a history of conflict or contestation. Knowledge of a landscape’s history necessitates re-situating the status of designer, from an operator over the inert object of land, to a more ambiguous, troubled identity, borne of a historic self-awareness.

I look forward to incorporating this awareness into my design process by asking a series of questions: What is a site’s inherited legacy? And to what extent do we expose or elucidate the histories embedded within space? In grappling with these questions, the land itself emerges as a figure the designer collaborates with for only a moment in its long history. In this relationship, we acknowledge the sovereignty of a land. I am deeply grateful to the symposium’s speakers for inspiring this critical dialogue, and for shaping the future of my engagement with landscape.

Estello Raganit, Master of Landscape Architecture candidate, 2019, Harvard Graduate School of Design

Landscapes of war are marked by the tactical manipulation of ground conditions, including the construction of military infrastructure, as well as literal lacerations, destructive formations, and chemical traces left behind on the earth’s surface. This year’s symposium expanded this field of thought, including under the label “landscapes of war” spaces inscribed into memory or produced as a consequence of conflict.

I was particularly interested in Pamela McElwee’s presentation, “An Environmental History of the Ho Chi Minh Trail,” and the ways in which the narratives and fictions surrounding the Vietnam War produced a mythologized understanding of the Ho Chi Minh Trail as a singularity, as opposed to an entire network of formal and informal trails of diverse ecologies. Landscapes of war are consequently reproduced in a cognitive space, just as they are produced in a physical one.

I also appreciated how the final presentation by Patrick Jennings, “Smashed to the Earth: Documenting, Remembering & Returning to the 9/11 World Trade Center Attack Site,” made way for conversations about landscapes of war as spaces of both shared and personal exploration. These particular landscapes are inherently subjective, and exclusive. After the lecture I spoke with Finola O’Kane Crimmins and Henk Wildschut about how spaces like the 9/11 memorial can actually prevent a transnational dialogue about landscapes produced as a result of deep trauma. These emotions can be shared to a certain extent. Thus, the landscape of war is more than the actual sites of contestation; it also comprises the networks and metabolisms that produce and perpetuate the collective memory, and in some cases trauma, of warfare. The landscape of war is not merely a place—it is, more importantly, a lens through which we can understand and give meaning to our surroundings.

Mellon Symposium Award

Sara Jacobs, PhD Candidate in History, Theory, and Representation of the Built Environment, 2019, University of Washington

The theme of military landscapes actively producing new forms of nature emerged over the two-day Military Landscapes symposium. As a landscape architect and historian, the focus on environmental expansion in the context of war raised a series of questions about how and what is valued as nature from a historical and design perspective.

Because war is generally framed as act of destruction resulting in environmental degradation and change, the idea that military landscapes could produce new forms of nature expanded my assumptions about what constituted a military landscape. Pamela McElwee spoke of the Ho Chi Min Trail as both a dynamic landscape with its own agency and as a bio-physical space produced through techno-military histories and local environmental knowledge. Kenneth Helphand’s narrative and Henk Wildschut’s photographs of gardens planted in refugee camps illustrated how nature is produced both as a connection to home and as a way of grounding oneself in the context of traumatic relocations. Their co-presentation of stories matched with images was particularly effective in this regard. Likewise, Astrid M. Eckert used the example of the now greenbelt border between former East and West Germany to explain how nature erases military histories through commodification.

Finally, Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn and Gert Gröning presented perhaps the most compelling story of nature produced in the context of war. Their historic analysis of plans for vegetation to be deployed as a nationalist strategy in Nazi Germany highlighted the ways nature is culturally manipulated towards national and ideological ends. Together, the speakers illustrated the ways landscape is always the result of the co-constitution of social natures. As I move forward in my studies, I am left with new ethical questions of how environmental change is measured, understood, and valued in the historic context of military landscapes.

Andrew Op't Hof, PhD Candidate in Geography, Rutgers University, Landscape Architecture

As someone trained in landscape architecture but currently attempting a PhD in geography, I often find myself betwixt and between academic disciplines and ways of knowing, and it was heartening to see such a distinguished array of scholars grappling with similar concerns at the Military Landscapes symposium. Though each presentation was fascinating, I found “Displaced Persons’ Gardens” by Kenneth Helphand and Henk Wildschut to be the one that most made me rethink my own work. I’ve previously written about the adaptive reuse of an abandoned military base in California. The residents I wrote about engaged in very much the same type of gardening, but often didn’t describe themselves as “displaced.” I must consider that part of the reason they do not is because of the gardens they’ve made.

In general, military landscapes might best be thought of as “landscapes of events,” as Antoine Picon so nimbly argued, yet these landscapes seem to ripple far and wide in both space and time, making it difficult, for me at least, to draw the line between causal conflict and landscape effect. As so many of these presentations illustrated, the practice of landscape itself is often a direct act of war. In my current work on the role of landscape in processes of gentrification, I must be diligent in considering landscape as a form of violence.

Simon Rabyniuk, Master of Architecture candidate, 2018, University of Toronto

I am thankful for the support of the Mellon Travel Award, which allowed me to attend the 2018 Garden and Landscape Studies Symposium on military landscapes.

The symposium’s presenters addressed diverse historical periods, geographies, and cultures. Taken as a whole, the symposium allowed me to develop an understanding of military landscapes that includes, but also exceeds, the products of military engineering, battlefields, and commemorative monuments. Many presenters extended the discussion of the symposium’s theme, and in doing so addressed military landscapes as larger territorial networks. Several examples of this include: Christine Ruane’s argument, which understood World War I Russian cities as military landscapes, even though they were physically far from any active fronts. Her analysis demonstrated how land-use policy changed based on war-time scarcity of food, transforming urban open spaces into allotment gardens.

Gert Gröning and Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn’s paper also extended the definition of what constitutes a military landscape. They documented National Socialist conceptions of “defensive landscapes” in the 1940s and how they were used as techniques for instrumentalizing landscape in the long-term occupation of other territories. Additionally, Pamela McElwee, in offering an environmental history of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, presented a complex ecology of human and non-human actors in which the forest’s triple canopy played a mediating role between air and ground. Lastly, Antoine Picon’s proposition, in which he considered landscapes as events, must be remembered. Because they consist of both planned and unforeseen circumstances, understanding landscapes as events suggests that circumstances constitute a landscape, rather than it having a preexisting status.

My research focuses on the integration of Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) into urban airspace. Numerous papers addressed military landscapes as large-scale, time-based systems, and as the products of social or political conflict facilitated by an application of technical knowledge. These ideas presented helpful theoretical and methodological approaches for framing systems that span large territories. This experience has been helpful in thinking through UAS as social, technical and political nodes within large scale networks that engage land, air, and low earth orbit.

Krista Reimer, Master of Landscape Architecture candidate, 2019, University of Pennsylvania

It was a great opportunity to attend this year’s Garden and Landscape Studies Symposium on military landscapes with the support of a Mellon Travel Award. Following a year which included both my own research into the effects of war on Westover plantation, in Virginia, as well as discussions with classmates regarding their study of war memorial design and militarized borders, my attendance at the symposium brought fresh ideas not only to my work, but also to these classmates, who I returned to after the symposium. Certain talks related clearly to these projects, providing either context or useful comparable case studies.

Altogether, the breadth of approaches to the topic of “military landscapes” provided a stimulating sample of the various ways war affects, and is affected by, landscape. I appreciated how this careful curation of range, with voices from various disciplines, forced a nuanced conception of the relationship between war and landscape. As a professional landscape architecture master student interested in pursuing research that looks at political aspects of landscape architecture, I am very much in the middle of trying to begin to articulate specific questions and research topics of interest to me. Each talk, as well as the symposium as a whole, was a helpful example of a possible way to address complex and/or contested issues. In terms of framing and representation, I have taken many lessons from it. My attendance at this symposium has been a wonderful first chance to visit Dumbarton Oaks. I hope to have the chance to visit again in the future.