You pass by the same park every day. It seems unmoving, unchanging, as if it has been there forever. How do you learn to see not what it is—what you know it has always been—but what it was in the past and what it might be? How do you teach others to appreciate its history and to imagine it in a more ambitious, innovative, and creative way?

Over the past two years, Jeanne Haffner, Mellon postdoctoral fellow in urban landscape studies at Dumbarton Oaks, has been building collaborative initiatives that foster humanistically grounded design skills in teenagers from Washington, D.C. Haffner’s programs connect Dumbarton Oaks’ resources in Garden and Landscape Studies (GLS) to two other educational institutions in the District: Phelps Architecture, Construction and Engineering High School and the National Building Museum’s Design Apprenticeship Program. Phelps High School is a public magnet school with strengths in math and science education; Dumbarton Oaks works with its architecture and landscape classes on a set of design challenges and field trips over the year. The National Building Museum’s apprentice program teaches thirty teenagers design fundamentals and tool skills while developing real-world projects over the course of nine five-hour Saturday sessions per semester; Haffner participates in select sessions as a teacher, mentor, and design critic.

She explains that the students in both programs often have strong technical abilities and practical intuitions, but thinking about design as a humanistic and artistic activity breaks new ground with them. For example, in late September 2016, Phelps High School students visited Dumbarton Oaks to learn about hydrology in its gardens, culminating with an activity: how would you redesign the irrigation in the Ellipse, with its double-ring of thirsty hornbeam trees? Haffner and the students discussed how climate change has caused problems with the irrigation system: because storms have grown heavier, rains don’t permeate the soil as much as they used to. “They had great questions—very logical questions about the trees, their needs, the pipes,” she recalls. “But they tend to think more like engineers than like landscape designers.” To point out the wide range of ways the space has been imagined over the decades, she showed them Farrand’s very different original design for the Ellipse, which led to a discussion about design history and how the use of different types of trees and other vegetation can give an area a completely different feeling.

Dumbarton Oaks, as a research center in the humanities, has the ability to complement the school’s curriculum by teaching the students how to see beyond the expectations and assumptions that the present time and culture have imparted. Haffner wants to help them see that “landscape design has an aesthetic component and is informed by ideas and techniques that have histories. They obviously have a strong science background. So I try to balance this important perspective with other, more humanistic, concerns. My aim is to make them aware that their own designs, like all designs, are subjective and tied to values. Far from being objective and scientific, their designs reflect cultural expectations about how humans should interact with nature, and these ideas about naturalness are historically rooted.”

In the 2015–16 school year, Haffner launched programming with a number of one-time workshops; in 2016–17, she is steering the initiative toward a more sustained, yearlong curriculum built around multiple workshops and field trips. In addition to Phelps High School’s workshop at Dumbarton Oaks, GLS facilitated a tour of the National Zoo with its landscape architect, Jennifer Daniels, and is working with the students on a monthly basis from February to May to redesign a community garden in northeast D.C.’s Kingman Park. Haffner explains that the project is an ambitious conceptual challenge: “How do you include a toolshed, stormwater management, plantings—on a hillside? The soil at the site is also toxic, meaning you need to use raised plant beds.” Haffner, along with John Beardsley, director of GLS, and Jane Padelford, GLS program coordinator, are participating in midterm and final design reviews with the school, lending professional expertise to the school’s curriculum.

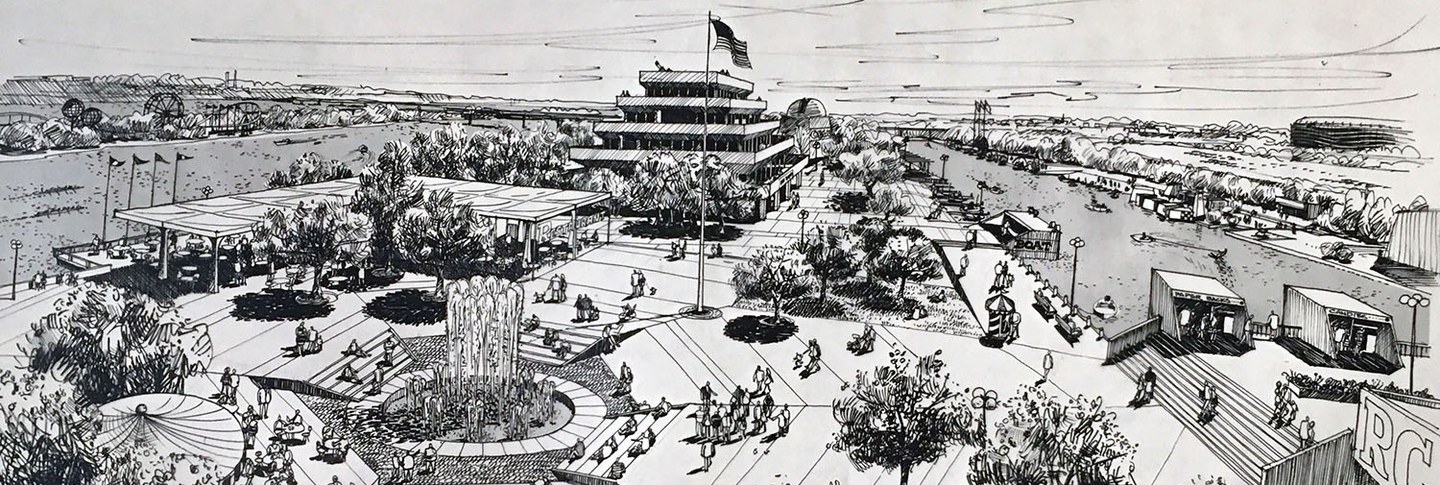

At the National Building Museum, GLS is also helping highlight the historical and cultural facets of landscape design by focusing on the city the students know best—Washington itself—and showing not just what it is, but also what it might have been. As a complement to a current exhibition on the landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, Haffner created a tour of the show that highlighted the contrast between Halprin’s unrealized plan for the Anacostia riverfront in the 1960s, the current reality of the riverfront, and plans for how modern architects would like to transform the area in years to come. “The Anacostia riverfront worked well as an example because many of the students reside there. It made Halprin’s work feel closer to home.”

Haffner hopes that the Dumbarton Oaks and Mellon Foundation initiatives will help change students’ sense of what architecture and design aim to do as disciplines, and broaden their conceptions of what they’re doing from the very beginning. “It’s difficult to teach both the technical and social aspects of design simultaneously. They’re beginners. So they need a simple model,” she acknowledges. “But I think the social, cultural, and historical aspects of landscape can and should be integrated into design pedagogy from the start, right up front—not added in at the end.”