When Chris Donnan first set out to photograph Moche vessels in the 1960s, he met with a problem. The art, often a continuous scene around a vessel, lost more than just a touch of its beauty when converted to two static dimensions. It lost coherence, and, to the extent that it became more difficult to study, it lost some of its scholarly value.

It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that Donnan perfected his technique for photographing the vessels that captured all their iconographic detail. Moving around the vessels, he took several shots of each from a set focal point; once printed, he cut the photographs up and spread them out. The resulting flattened scenes made iconographical research faster and less arduous. Donnan’s research partner, Donna McClelland, then drew the newly arranged images on half-matte acetate, further “unwrapping” the scene and creating a final fluid depiction.

![]()

The Moche Archive, created by Donnan and McClelland and now housed at Dumbarton Oaks, has recently undergone another conversion aimed at enhancing its scholarly use: we are launching an online portal in English and Spanish to access nearly eight hundred of McClelland’s “rollout” drawings.

The physical archive, comprising over 100,000 photographs, slides, negatives, and drawings, has long been a significant scholarly resource, offering insight into aspects of the Moche world as diverse as flora and fauna, rituals and mythologies, and communication pathways. For nearly three decades, Donnan photographed painted vessels from more than two hundred public and private collections, resulting in a remarkable, and remarkably accessible, compilation of images.

The online portal provides access to high-resolution scans of fineline drawings made by McClelland. The rendering of a Moche vessel’s iconography presents an obvious set of challenges, similar in some ways to the production of a two-dimensional map of the world. Simply flattening the image is not enough; the original interplay of compositional elements has to be considered and attempts made to preserve it. “That’s one of these techniques McClelland was able to master,” says Ari Caramanica, a Tyler fellow who worked on the portal, explaining that it’s not easy to take a globular work and turn it into something easily legible, especially for scholars working from print or digital resources.

McClelland did, and she managed to create more than just a highly valuable scholarly resource. Her fineline drawings—precise, fluid, composed in stark black and white—are art objects in their own right. “She typically traced the imagery with a drafting pen in order to unwrap it, but then she did a lot of her work freehand too,” explains Pre-Columbian Studies Librarian Bridget Gazzo. “And the drawings are so beautiful, so llamativa—so attention-grabbing.”

![]()

McClelland’s drawings, which make the thematic content of the vessels’ decoration more apparent, were thoroughly categorized by Donnan and McClelland according to content and recognized figures in the images. Keeping this original categorization intact, Dumbarton Oaks has added terms and identifications from other well-known publications. As part of her institutional project, Caramanica created descriptive cataloguing and access terms for the nearly eight hundred digitized fineline drawings, a process that often relied heavily on Donnan and McClelland’s own published scholarship on Moche iconography.

Because Caramanica’s dissertation research, on agricultural landscapes of pre-Hispanic Peru, partly involves the Moche period (AD 200–900), the project allowed her to study the Moche’s unique environmental perspective. “The Moche are constantly depicting their natural environment and their daily life,” Caramanica explains. “And because it’s related to my research, I’m particularly interested in seeing how they depict the desert—how they conceive of it, what kind of activities take place there, and so on.”

![]()

One reason the fineline drawings—and Moche iconographical studies more broadly—are so significant is that we don’t have any systems of writing for the Andean region. In this absence, the art and iconography of Andean cultures take on a higher function, illuminating aspects of life that might otherwise have gone in a written record. Moche iconography, thanks to its stylistic choices, offers a particularly profitable set of images.

The vessels and their corresponding fineline drawings show an astonishing variety of figures and scenes. Animals, humans, and supernatural entities abound, as do scenes of ceremonies and quotidian tasks: deer hunting motifs, one-on-one battles, humans dressed for their everyday activities or garbed in highly stylized ritual attire, golden goblets being passed, and blood being let, spraying black droplets across the background.

![]()

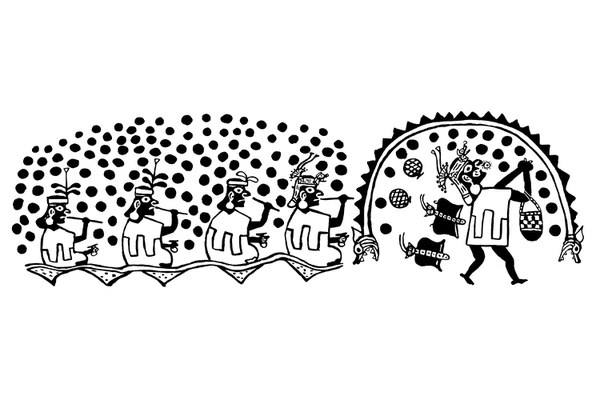

Perhaps one of the most intriguing motifs centers around beans. In one scene, ritual runners, carrying bags in their hands, move through a field of vegetation. The scene is stippled with black-and-white amoeboid shapes: the beans. “We know at the time of Spanish arrival that the Inca had this system of runners to transmit messages or to deliver goods, and we think that’s what this represents,” Caramanica explains. Similar bags containing bicolored beans have cropped up during excavations. The ratio of black to white in the beans, likely connected to climatological factors, might have been used as a way of recording information; “the theory is that these beans may be some sort of counting device, or at least some sort of signaling device.”

Other scenes develop the bean motif further. Anthropomorphized bean warriors with delicate, dancer-like legs do battle with deer-headed figures. In running scenes, the runners themselves gradually morph into beans, or, as in a classic example of a spiraling scene, beans set off, slowly gathering human features as the images ascend.

![]()

“Most of the forms of iconography or expression ante- and postdating the Moche are either very geometric and abstract, or so supernatural and mythical that it’s difficult to interpret how the depicted figures might relate to the real world,” Caramanica explains. “The Moche are not only extremely realistic in their image-making, they also tend to repeat those images in different scenes, which makes it easier to identify, for instance, a husk of corn, or a particular character who reappears in scene after scene.”

These features—a lower level of abstraction than other Andean iconographical programs and a firm representational connection to the real world—are a large part of the style of Moche iconography. Prisoners are depicted with ropes around their necks, facial hair, and tattoos—descriptions that match up with mummies excavated at Moche sites. As Caramanica explains, with the Moche, “the archaeological record is so complete and well preserved that oftentimes we can excavate a tomb or architectural site and pull out objects we’ve seen in the fineline images, or even bodies that are depicted in some of these images.”

![]()