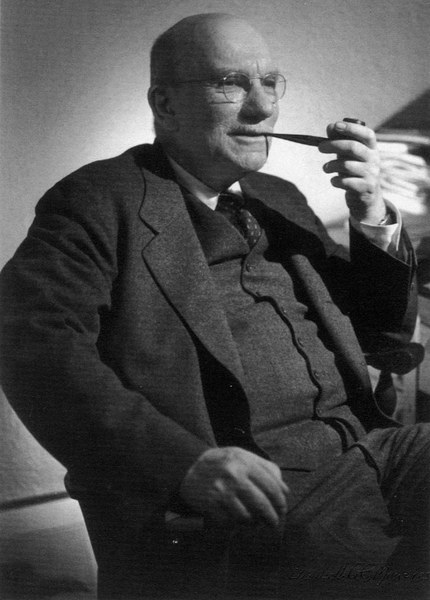

Albert Mathias Friend, Jr. (1894-1956).

Although the medieval art historian Albert “Bert” Mathias Friend Jr. was a Princeton University professor, he was also a significant presence and influence on Dumbarton Oaks in its early years. Friend was both an undergraduate student, beginning in 1911, and graduate, beginning in 1915, at Princeton, but because of the First World War he did not complete his doctoral work. After the war, beginning in 1921, he became an instructor and, in 1946, a professor at Princeton, succeeding Charles Rufus Morey as Marquand Professor of Art and Archaeology. In 1943, he was appointed a member of the Board of Scholars at Dumbarton Oaks. He became a resident scholar from 1944 to 1946 and Henri Focillon Scholar in Charge of Research in 1947–48. He was then named director of Byzantine Studies in 1948, a position he held through 1954. During his appointments at Dumbarton Oaks, Friend retained Princeton faculty status, typically spending one of the academic terms in Princeton and one in Washington. Despite his split responsibilities, Friend often is credited with developing Dumbarton Oaks into a premier Byzantine studies center.

Arriving at Dumbarton Oaks just before the end of the Second World War, Friend recognized the opportunity to restructure the institute in anticipation of the return of Byzantine scholars who had served abroad during Dumbarton Oaks’ first years as a research institute. He simultaneously worked to better unite Dumbarton Oaks with Harvard’s academic center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Friend reorganized the fellowship structure: junior fellowships were to be awarded to younger scholars for a period of one or two years, while senior scholars would be granted both academic rank at Dumbarton Oaks and membership in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. In this capacity, senior Dumbarton Oaks scholars could be invited to offer courses related to their work in Cambridge and would be given more incentive to publish their work.

However, according to his colleague, the Byzantinist art historian Kurt Weitzmann, it was the symposia organized by Friend which established Dumbarton Oaks as one of the leading institutions in Byzantine studies. During Friend’s tenure, Dumbarton Oaks hosted symposia on such diverse topics as “Portraits and Biographies in Byzantine Manuscripts” (1944), “The Decorations in the Synagogues of Dura-Europos” (1945); “Hagia Sophia” (1946), “Byzantine Art and Scholarship” (1947); and “The Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople” (1948). For these symposia, Weitzmann noted that Friend attracted the “very best scholars from all over the world” and often got them to come not only as speakers, but also to stay for a term or a year as Visiting Scholars in order to collaborate on the symposia with their colleagues. These scholars included Milton Anastos, Sirarpie Der Nersessian, Glanville Downey, André Grabar, Carl Kraeling, Paul Underwood, and Alexander Vasiliev.

Believing that a narrow academic focus restricted intellectual progress, Friend devoted much of his time at Dumbarton Oaks to encouraging the study of interests outside of art history. Not wishing for Dumbarton Oaks to fall into the myopic trap of limited academic specialization, Friend worked diligently to expand the scope of the institution’s studies to include history, theology, law, liturgy, philosophy, and music. It was with this goal in mind that Friend encouraged collaborative and multi-disciplinary research on the symposia that he organized and administered. This broad-palette approach to scholarship provided Dumbarton Oaks with an interdisciplinary intellectual edge that was meant to be superior to the university’s isolated academic department approach to scholarship.

After three years of illness, Friend died in 1956. His friend and colleague, Milton Anastos, remembered him years later:

Friend was an unusually gifted Byzantinist and had a genius for stimulating research both at Dumbarton Oaks and at Princeton. He himself never published more than about five articles, but he inspired a large number of projects, primarily in the field of Byzantine art and archaeology. Although he never completed any part of the great work he had planned, he gave the impetus to others who carried out the schemes he had adumbrated. He had an encyclopaedic and unexcelled knowledge about all of the relevant monuments. But his skills lay in imparting ideas and providing trenchant criticism. He spent a great deal of time, at the expense of his own projects, in encouraging others.

Albert Friend wrote two insightful letters, of November 7, 1945, and November 2, 1946, to Paul Sachs, chairman of the Dumbarton Oaks Administrative Committee, describing Dumbarton Oaks and outlining its aims for the future.