James N. Carder

Passion is rare; but it is convincing when it does appear. The man who has a passion cannot live without working to attain the object that inspires it.

Royall Tyler, 1909

The correspondence of the period 1909–1919 coincides with Robert Woods Bliss’s foreign postings in Brussels, Buenos Aires, and Paris. It also covers the entirety of World War I. The correspondence from this period is relatively meager due, in part, to the war and to the close proximity of Royall Tyler and his wife, Elisina, to the Blisses, all of whom lived in Paris. During the decade covered by this correspondence, Royall Tyler grew significantly as an art connoisseur and scholar, and his letters document how thoroughly he imparted to the Blisses his passion for art and how he advised them as collectors. The artworks that the Blisses acquired during this period—French Gothic sculptures, western medieval tapestries, Islamic ceramics, Pre-Columbian objects, and a French Impressionist painting—are as much a record of Royall Tyler's interests and erudition as they are a record of the embryonic stage of the great collection of the Blisses.During this period, the Blisses purchased English antique household furnishings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, important but small-scale western medieval tapestries (HC.T.1908.01.[T], HC.T.1912.03.[T], HC.T.1913.04.[T], and HC.T.1915.01.[T]), French Gothic sculptures (BZ.1912.2 and HC.S.1919.001.[S]), a seventeenth-century Chinese portrait scroll (HC.P.1919.03.[WC]), and Persian Islamic glazed bowls (BZ.1916.1, Ex.Coll.HC.C.1912.04.[TC], Ex.Coll.HC.C.1913.02.[EW], and Ex.Coll.HC.C.1918.01.[TC]). Robert Woods Bliss acquired at least twelve Pre-Columbian objects in 1913 and 1914, including the Olmec jadeite figurine (PC.B.014) that planted the “collector’s microbe” in Bliss (Ex.Coll.PC.B.467, PC.B.042, PC.B.444, PC.B.445, PC.B.469, PC.B.474, PC.B.475, PC.B.479, PC.B.480, PC.B.482, and PC.B.483). Mildred Barnes Bliss continued to acquire Old Master prints (e.g., The Nativity (HC.PR.1910.10.[En]) by Albrecht Dürer), and the Blisses famously acquired an Edgar Degas canvas (HC.PR.1918.02.[O]) from the 1918 Vente Degas. Of interest is the fact that the Blisses acquired no Byzantine artworks during this period, although they began to acquire a few objects from ancient cultures such as a Caucasian or Crimean (?) bronze quadruped animal (BZ.1913.1) and a sixteenth-century silver bowl from Dalmatia (BZ.1913.3), which they believed to be Sassanian.

Begin reading letters | Search all letters

Foreign Postings

After their wedding on April 14, 1908, the Blisses spent a brief honeymoon at Mildred Barnes Bliss’s house in Sharon, Connecticut. Within a few days of the wedding, Mildred Barnes Bliss’s mother, Anna Barnes Bliss, established a trust fund for Robert Woods Bliss,Anna Barnes Bliss to Mildred Barnes Bliss, April 16, 1908, Blissiana files, Anna Barnes Bliss correspondence. and Mildred wrote to her stepfather: “My head & heart were never clearer than at the altar Tuesday. I was conscious of everything my vision has yet reached—of achievement & failures of regrets & partings & the affection & fore-thought & satisfaction of all the years I have known you & Mother & Sister. But all of me was ready for that hour & through & through I was glad for life & love & youth. I believe in Robert & have confidence in myself & am supremely content.”Mildred Barnes Bliss to William Henry Bliss, April 17, 1908, Blissiana files, William Henry Bliss correspondence. Later, Robert Woods Bliss offered similar sentiments to his father: “The perfect understanding between Mildred and me, our full confidence in and love for one another has not left anything wanting in the fulfillment of our hopes and beliefs. . . . Ah! Dad I am happy,—fully, completely, utterly; Mildred has brought all beauty and joy into my life.”Robert Woods Bliss to William Henry Bliss, April 23, 1909, Blissiana files, William Henry Bliss correspondence.

A little over a week after the wedding, the Blisses sailed for England on the SS Cedric, and after a day of shopping and visiting museums in London,Robert Woods Bliss to William Henry Bliss, April 23, 1909, Blissiana files, William Henry Bliss correspondence. they continued on to Brussels so that Robert Woods Bliss could resume his work as secretary of the U.S. legation. In Paris, they made their first art acquisition as a married couple, selecting an important small Flemish tapestry.HC.T.1908.01.[T]. The piece was purchased as a wedding gift from Anna Barnes Bliss, and was offered on long-term loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In Brussels, Mildred Barnes Bliss began a self-directed study of Belgian medieval architecture,See correspondence with Clement Heaton, Bliss Papers, HUGFP 76.8, box 20. Heaton also appears in Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, undated letter [2] (after April 7, 1912); and Elisina Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, April 1, 1913. and frequently visited the city's museums and libraries. After one visit to the Bibliothèque Royale, she wrote in her diary: “Heavenly hour at Bibliothèque. . . . I wonder which lends itself most to pictorial expression, the emotional religion of the latins or the intellectual religion of the Flemish? One would say off hand the latter, but the Italian primitives had a naïf sense of correlative & appropriate detail which gave great beauty to their borders and backgrounds. Of course XVI cent. realism cost them their aesthetic charm—& in this respect the north suffered as well. There is in the Bibliothèque a livre d’heurs more pure in its conceptions & colours than anything I know. Fra Angelico alone excepted.”Mildred Barnes Bliss, diary, March 3, 1909, Bliss Papers, HUGFP 76.8, box 45. The manuscript referred to is Brussels, Bibliothèque Royale, MS 11060-61 (Très Belles Heures, Franco-Flemish, fifteenth century). Despite Mildred Barnes Bliss's hope that Royall Tyler would come to Brussels to “plunge into Flemish things,” the Blisses saw little of him except during a visit to Paris in July 1908. He told them that he could not come to Brussels until the next spring, as he was preoccupied with work on a book, Spain, a Study of her Life and Arts, that would be published in July 1909. In Brussels, Robert Woods Bliss began corresponding with his father about his diplomatic career. He wanted to be advanced to a secretary posting at an embassy, but only if the promotion came in recognition of his abilities and not as a political favor. But he also advised his father that he did not want his career advancement to be too rapid, recognizing that he acquired “matters and experience slowly, but surely.”Robert Woods Bliss to William Henry Bliss, November 2, 1908, Blissiana files, William Henry Bliss correspondence.

With his father’s influential help, on August 4, 1909, Robert Woods Bliss was appointed first secretary of the U.S. legation in Buenos Aires. Pleased with the prospect of being in Argentina, the Blisses returned to New York in October so that Robert could undergo a minor medical procedure; then, they undertook an overland crossing of the Isthmus of Panama, traveling down the west coast of the continent, visiting Lima and Santiago, crossing the Andes on the Transalpine Railroad (and, at times, on muleback), and arriving in Buenos Aires in November. Mildred Barnes Bliss wrote her stepfather that “the trip will be wonderful & I fancy we may even like the place itself.”Mildred Barnes Bliss to William Henry Bliss, August 24, 1909, Blissiana files, William Henry Bliss correspondence. Argentina, however, soon came to feel isolated and remote, and Mildred Barnes Bliss characterized their life in Buenos Aires to Elisina Tyler as “bustling stagnation and crowded solitude of the intolerably superficial existence our ‘career’ obliges us to lead in this babylonish midst. It takes all our will to keep our lantern trimmed each day and I pray constantly for the strength to hold my inner self intact, until another year shall end this severe schooling. We watch one another with hawk’s eyes to pluck out any signs of incipient deterioration and thus far we are clean.”Mildred Barnes Bliss to Elisina Tyler, September 17, 1910. Toward the end of their posting in Argentina, she wrote to a friend, “we both feel deplorably stale intellectually and crave a new mental cord. We went en grève [“on strike”] one evening last week and read Keats and Shelly aloud, but that way lies discontent, so we returned to the practical!”Mildred Barnes Bliss to Mrs. Sherrill, October 25, 1910, Blissiana files, Sherrill correspondence.

This all changed when Robert Woods Bliss was appointed secretary of the U.S. embassy in Paris, a position he eagerly took up in March 1912. He was later promoted to counselor of the embassy on July 17, 1916. In Paris, the Blisses first resided at the Hôtel Bristol, Place Vendôme, until they found an apartment on the Avenue Henri Moissan in March 1913. Paris offered the Blisses sophistication and culture. Mildred Barnes Bliss excitedly wrote her stepfather: “We have heard Kreisler Friedrich “Fritz” Kreisler (1875–1962), an Austrian violinist who was one of the most famous violin virtuosos of his day and who is regarded as one of the greatest violinists of all time. play, and play divinely, the Viotti and Vivaldi concertos. He never seemed to me in better form; it was superb, and a great pleasure to me to see how Robert delighted in it and discriminated.”Mildred Barnes Bliss to William Henry Bliss, February 11, 1913, Blissiana files, William Henry Bliss correspondence. In Paris, the Blisses would mature into serious, life-long art collectors, and Royall Tyler would become their principal adviser and confidante.

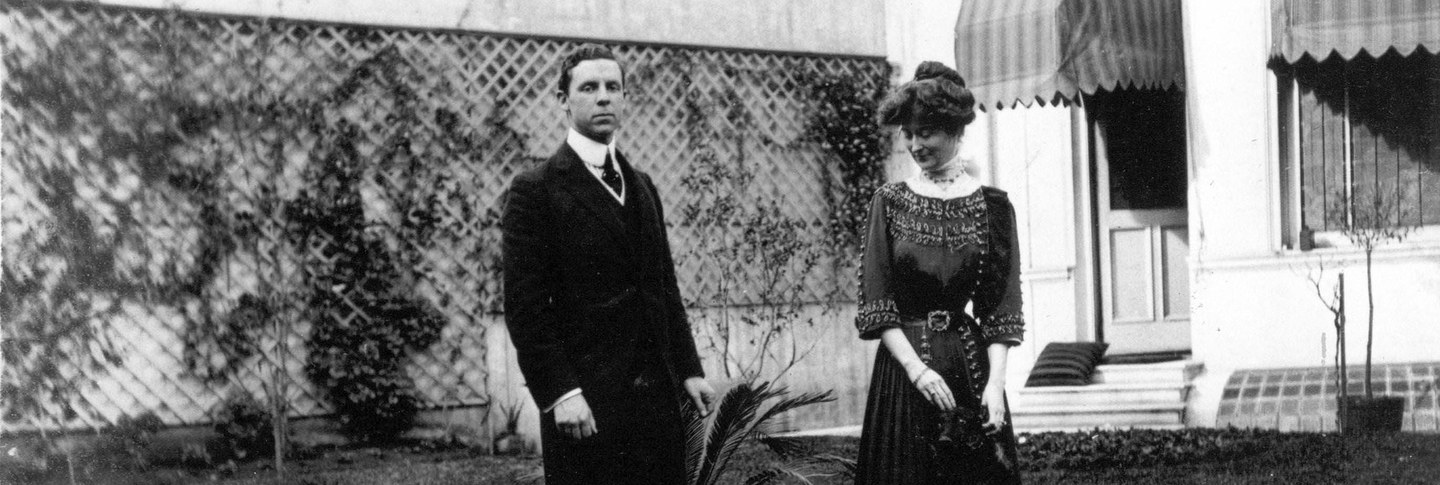

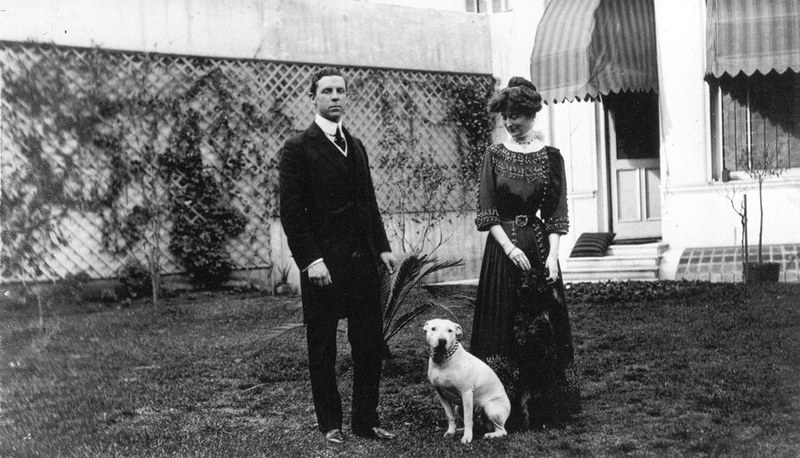

Royall Tyler and Elisina Grant Richards

Royall Tyler's work on his Spanish art book brought him to London in March 1909, where he met with his publisher, Grant Richards. Franklin Thomas Grant Richards (1872–1948) opened his London publishing house in 1897, and established his reputation when he published George Bernard Shaw's Plays Pleasant and Unpleasant and A. E. Housman's A Shropshire Lad in 1898. That same year, Richards married the Florentine Elisina Palamidessi de Castelvecchio, the daughter of Francesco Palamidessi and Contessa Joséphine de Castelvecchio; they had four children: Gioia Vivian Mary Elisina (1900–1969), Gerard Franklin (1901–1916), Charles Geoffrey (“Carlos”) (1902–1959), and Geoffrey Herbert (1906–1983). In 1902, Grant Richards moved his business into larger London offices, which led to bankruptcy in April 1905 and required that he reorganize the firm with his wife’s backing and add her initial to his imprint (E. Grant Richards). Richards was also a novelist and published eight novels, beginning with Caviare in 1912. In the last decades of his life, he wrote and published what amounted to a three-volume memoir: Memories of a Misspent Youth, 1872–1896 (1932), Author Hunting by an Old Literary Sportsman: Memories of Years Spent Mainly in Publishing, 1897–1925 (1934), and Housman, 1897–1936 (1942).For Grant Richards’s biography, see William S. Brockman, “Richards, (Franklin Thomas) Grant (1872–1948),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

It is likely that Royall Tyler first met Elisina Grant Richards in 1908 when he entered into discussions with Grant Richards concerning the publication of Spain, a Study of her Life and Arts. This is corroborated and amplified in letters that Royall Tyler and Elisina Grant Richards separately wrote to Mildred Barnes Bliss.Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, April 12, 1910; and Elisina Grant Richards to Mildred Barnes Bliss, August 20, 1910. On April 12, 1910, Royall Tyler wrote that he met and immediately fell in love with Elisina Grant Richards about a year and a half before. Indeed, when the Blisses came to London in May 1909, Royall Tyler could not meet them as he was staying at Elisina's cottage in Cornwall.Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, June 22, 1909. Royall Tyler's affair with Elisina Grant Richards resulted in her leaving her family that August and starting a new life with Royall Tyler, events that are chronicled in large part in the Bliss–Tyler correspondence of this period. The couple spent the winter of 1909–1910 together in southern Italy, and by the fall of 1910 were living together in Paris at 8, rue de la Barouillère.The rue de la Barouillère is today the rue Saint-Jean-Baptiste de la Salle in the sixth arrondissement of Paris. The building at 8, rue de la Barouillère, now demolished, was constructed in 1879. See “Lettre ‘L’ (de ‘rue de La Barouillière’ à ‘rue La Vrillière’),” Paris 1876–1939: Les permis de construire (blog), February 7, 2010. On October 17, 1910, the Tylers’ son, William Royall Tyler, was born, and Mildred Barnes Bliss was made his godmother.

Before her departure from England, Elisina Grant Richards had been editor of The Englishwoman, a progressive art and sociopolitical periodical created for her by Grant Richards, which published its first number in February 1909. The seventh issue (August 1909) published her reviews of Cicely Hamilton’s Marriage as a Trade and Royall Tyler's Spain, a Study of her Life and Arts. “The Silent Company of Books,” The Englishwoman 3, no. 7 (August 1909): 112–22. Elisina Grant Richards tellingly welcomed Marriage as a Trade as “an eloquent, impassioned plea for the mere recognition of an accomplished fact—the existence of woman as an individual, and not as a being complementary to man: Our laws concerning women are undoubtedly those which represent with least fidelity the customs and opinions of our day. The spirit of them is broken by daily practice. The spirit of the law with regard to women is to consider them as complementary to man—the man is the head of the family. Our laws do not take into consideration women as social units. This arbitrary condition cannot endure much longer, for public opinion, based on a common-sense recognition of facts, is against it. But it is strange how long the husk will hold together before it finally decays and breaks.”

Elisina Grant Richards also praised Spain, a Study of her Life and Arts as an ideal guide book, one that was unromantic due to Royall Tyler’s knowing his subject well enough to discard conventional ideas about it. Indeed, Bernard Berenson, the Italian Renaissance art connoisseur, would later use the book as a guide for a trip to Spain and was “touchingly grateful for indications” in the book.Royall Tyler to Elisina Tyler, August 26, 1919: “I had much talked with Berenson who really saw Spain well and was touchingly grateful for indications in my book. He spent some time with Utrillo and Unamuno and enjoyed them immensely, it seems. He is very attractive when like that.” From a transcription of tape-recorded excerpts of correspondence made by William Royall Tyler at Antigny-le-Château in 1972, see Wharton mss., box 11, The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Mildred Barnes Bliss's acceptance of the relationship between Royall Tyler and Elisina Richards—although the particular circumstances gave her pain—and the Blisses’ decision to lend financial aid to Grant Richards's business in order to better provide for Elisina Richards's children are poignantly detailed in the Bliss–Tyler correspondence. Elisina Richards had explained to Mildred Barnes Bliss in a letter of August 20, 1910, that “[m]ost women in my position would have given you a different reason [for why they did not leave their husbands earlier]: the children. But I have known in my heart for a few years past that I was being so hemmed in and badgered that in a short time I would have been no use to them—no use as myself, though outwardly still a kind of tutelary presence to which their eyes were accustomed. As it is I shall be there when they need me, quite strong and ready to help them.” Of interest in understanding Mildred Barnes Bliss's acceptance of this situation is her nearly contemporary appraisal of a Buenos Aires woman in an adulterous relationship, which she wrote on October 25, 1910, to Mrs. Sherrill, the wife of the U.S. minister to Argentina: “The city is showing a callous cynicism utterly contemptible. No one stands by Mme. De G[ainza] and Mme. R. L[arreta] has become a matter of great curiosity. I have not seen her out for a fortnight. It is the story of Hedda, and I fear the same solution. With a bad inheritance, faulty upbringing, intolerant husband, dull surroundings and an erotic nature craving emotion at crises, the poor woman is headed straight for disaster. She told a friend her only salvation would have been the stage; and a pistol is by her constantly. All this leads to many reflections: among others, the lack of independence inculcated by Roman Catholicism, and the incapacity to cut clear and work. Why not have left R. L. long ago? ‘The children’ is really no answer. It is worse to bring them up to scent hypocrisy and temper and misery and deceit, than it is to give them less material advantages and a decent atmosphere, and the fibre that would come of some obstacles. It’s a bad business, all this, and I very much fear that some day B[uenos] A[ires] will awaken to a grim denouement.”Mildred Barnes Bliss to Mrs. Sherrill, October 25, 1910, Blissiana files, Sherrill correspondence.

The Bliss Inheritance

On September 30, 1911, the date of her fifty-third birthday, the Blisses’ stepsister, Cora Fanny Barnes, was instantly killed when she fell from her fourth-floor townhouse window at 6 East Sixty-Fifth Street in New York City. The event was reported by the police as a suicide, although the coroner later determined the death to be accidental. “Miss Barnes Killed by Fall on Birthday; Suicide the Police Say, but Coroner Feinberg Says 70-Foot Drop Was Accidental; Member of Colony Club; Recently Recovered from a Nervous Breakdown, and Just Returned from an Auto Tour of New England,” New York Times, September 30, 1911. Barnes had suffered from a nervous breakdown in 1909, and the Blisses had been told in 1910 that “the doctors think the illness will be of long duration and that there are occasional attempts at personal violence.”Robert Woods Bliss to William Henry Bliss, January 21, 1910, Blissiana files, William Henry Bliss correspondence. Somewhat surprisingly, her will left almost the entirety of her five-million-dollar estate to Mildred Barnes Bliss, “Miss C. F. Barnes Left $4,952,195; Mrs. Robert W. Bliss, Her Half Sister, Inherits Nearly All of the Estate; Fortune Built on $25,000; Testatrix, Who Was Killed by Fall from Window, Was Daughter of Castoria Maker,” New York Times, August 8, 1914. according to the probate record, which wasn’t made public until August 1914. At the time of the disbursement, the estate value was $5,196,596, of which Mildred Barnes Bliss received $4,536,487 as well as an emerald and diamond ring and necklace valued at $8,400. Anna Barnes Bliss was paid $42,823 and received an interest in realty valued at $223,823; William Henry Bliss received a Whistler painting, A Woman Carrying a Jug; and Robert Woods Bliss received Whistler etchings valued at $700. “Miss Barnes Left $5,196,596 Estate; Stepsister of Woman Killed in Fall from Window Receives $4,536,487; Stepmother Gets $42,823; New York School of Applied Design for Women and Kindergarten Association Are Beneficiaries,” New York Times, February 4, 1915. This inheritance and the 1923 sale of Mildred Barnes Bliss's holdings of Centaur Company stock propelled the Blisses into a category of wealth that would allow them to begin, albeit cautiously, to collect art seriously. The correspondence of this period is a chronicle of the beginnings of the Bliss collection.

Connoisseurship and Collecting

Royall Tyler's influence on the Blisses’ taste in art and on their collecting preferences in this period is nothing less than remarkable, and he was instrumental in formulating the Blisses’ collecting interests for the remainder of their lives. As the correspondence demonstrates, he introduced them not only to his first love, Byzantine art, but also to art from the Pre-Islamic Near Eastern, Islamic, ancient Chinese, and Pre-Columbian cultures, as well as to contemporary (Post-Impressionist) French art. All of these lay somewhat outside the mainstream of collecting of the time, and all offered the collector an affordable marketplace and the adventure of discovering less-studied traditions in which to hone their erudition and connoisseurship. In an article published in the first volume of The Englishwoman (February 1909), Royall Tyler offered his views on the modern collector and the newly opened avenues of collecting: “Passion is rare; but it is convincing when it does appear. The man who has a passion cannot live without working to attain the object that inspires it. The man who has a passion for painting—and I am now speaking of the public not the producers—cannot live without pictures. By hook or by crook he will possess and handle and see pictures; and he will have some true knowledge of them. . . . Art is much wider and more complicated than it was half a century ago. Modern foreign schools, the once despised periods of the art of the past, the arts of all the ages and all the nations, are biting and scratching in the space which was once reserved for the best-behaved Italians and Netherlanders, a few Frenchmen, Englishmen and Spaniards. The old rules can no longer be applied. No one is content to observe them.” “Essays on Masterpieces—I,” The Englishwoman 1, no. 1 (February 1909): 76–77.

In 1910, Royall Tyler traveled to Munich to see an exhibition of Islamic art, Meisterwerke muhammedanischer Kunst, Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde München, 1910. and he wrote about it in the Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science, and Art, revealing his delight in discovering little-known art traditions as well as his preference for non-realistic art, a preference similar to the one articulated by Mildred Barnes Bliss in her diary entry describing her Bibliothèque Royale visit. He wrote: “The early pottery . . . has not been known long enough for its importance to be realised widely yet. . . . The potters of Rhages, Sultanabad and Veramin could draw and model indeed! They could interpret every living being’s every movement, from the elephant’s heavy tread to the frightened rush of little fish in shallow water. . . . Their art has nothing to do with exact representation; not many years ago Europe would have been unprepared for it, unable to understand its supreme inventive genius. But now a few bold spirits have shaken off the ‘true-to-life’ superstition* and are strong in their new faith that if an artist does not copy slavishly what is before him it is not necessarily because he can’t. In this temper of mind alone is it possible to approach the pottery of the nearer East.” At the asterix, the editor felt obliged to interject: “This is, of course, a purely private opinion.—Ed. S.R.” Royall Tyler, “Mohammedan Art at Munich,” Saturday Review, July 23, 1910.

Tyler returned to the subject in another volume of the Saturday Review: “These Persian draughtsmen were extremely sophisticated; they simplified and cut down lines to the very essentials; they studied the fat, soft curve of a woman’s wrist, the round, almost featureless moon-face of the maiden of blushing fifteen, and rendered them with a sense of character and a malicious delight in the roly-poly chubbiness of the little harem beauties that borders on caricature. . . . Islam itself could not change Persians and dwellers in Mesopotamia from what they have always been: artists, poets and inquirers into the secrets of nature.” Royall Tyler, “Primitive Persian Art,” Saturday Review, November 19, 1910.

Indeed, by 1911, Royall Tyler had conscientiously refined his artistic interests. When Mildred Barnes Bliss asked him to come to Buenos Aires to advise her on, presumably, Renaissance paintings, he responded that he could not do this; that he had worked to obtain a knowledge of “two things—Persian pottery and French medieval sculpture.” He professed to be incompetent on most other subjects: “I have studied Near-Eastern and Spanish pottery, and medieval sculpture and architecture—outside Italy—too hard to have much energy left for other schools, and for the rest my preferences have taken me to primitive or quite modern painting, and to textiles, so that of all the schools I might conceivably know something about, those you want my advice on are my very weakest points. For years I have hardly looked at any but a few of the greatest men of the Renaissance. Rubens for me is a god, so is El Greco and Rembrandt. . . . But when it comes to the rest of Renaissance painting, I really know nothing about it at all, nor do I care at present.”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, June 26, 1911. By January 1912, he had enlarged his areas of study: “I never let slip a chance of seeing Gothic sculpture or Persian pottery, or as far as I can, early Chinese things. I never have cared very much for Japanese art, and Chinese porcelain also leaves me cold.” In early Chinese ceramics he found “[t]he greatest refinement and delicacy in shapes, and a nobility of matter in body and glaze unknown to Persia.”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, January 22, 1912.

In Royall Tyler, the Blisses recognized a true connoisseur, and they came to rely on his erudition regarding both the quality and authenticity of artworks. In 1908, the Blisses had quite successfully acquired, on their own initiative, an important Flemish tapestry.HC.T.1908.01.[T]. When they showed Royall Tyler a photograph, he exclaimed: “I know the original! Unless I am very much mistaken indeed it was at a dealer’s in Paris a year or two ago. It is a magnificent piece and I am delighted that you have it.”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, March 20, 1909, But in 1908 the Blisses also acquired on their own a Gothic Virgin that proved to be a forgery. Mildred Barnes Bliss wrote her stepfather: “the little Gothic Virgin we bought five years ago has come on from Brussels and we have decided to our dismay that she is [an] unadulterated fake: the final judgment has yet to be passed, but I have a shrewd suspicion that she spells the price of our initiation.”Mildred Barnes Bliss to William Henry Bliss, February 11, 1913, Blissiana files, William Henry Bliss correspondence. The final judgment against the piece almost certainly came from Royall Tyler. From this date forward, the Blisses sought his advice and opinion on most of the artworks that they were considering.

Royall Tyler strongly encouraged the Blisses to collect, often recommending artworks that he had discovered on the market, and he therefore became their adviser on the majority of collecting opportunities that they encountered. For example, Robert Woods Bliss famously recalled his introduction through Royall Tyler to Pre-Columbian art: “Soon after reaching Paris in the spring of 1912, my friend Royall Tyler took me to a small shop in the Boulevard Raspail to see a group of Pre-Columbian objects from Peru. I had just come from the Argentine Republic, where I had never seen anything like these objects, the temptations offered there having been in the form of colonial silver. Within a year, the antiquaire of the Boulevard Raspail, Joseph Brummer, According to William Royall Tyler, Royall Tyler had known and helped Joseph Brummer when he was a young and struggling dealer selling Japanese prints from a wheelbarrow in Paris. Typescript, 205. See also Elizabeth P. Benson, “The Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art: A Memoir,” in Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past: A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 6th and 7th October, ed. Elizabeth Hill Boone (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1993), 18. showed me an Olmec jadeite figure. That day the collector’s microbe took root in—it must be confessed—very fertile soil. Thus, in 1912, were sown the seeds of an incurable malady!” Robert Woods Bliss, Preface to Robert Woods Bliss Collection, Pre-Columbian Art: Text and Critical Analyses by S. K. Lothrop, W. F. Forshag [and] Joy Mahler, with a Preface by Robert Woods Bliss (London: Inaidon Press, 1957), 7–8.

During their years together in Paris, Royall Tyler admonished the Blisses to acquire a French Gothic Virgin and Child sculpture:BZ.1912.2. “[Y]ou and Mildred must not on any account omit to look at it. There is nothing so fine in the Louvre; and the Keeper of the Sculpture at S. Kensington, whom I took to see it, says it is finer even than Mr. Morgan’s famous and rather similar one.”Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, May 27, 1912. He enticed them to collect early Chinese art: “What I really enjoyed was the white Sung jar. A most beautiful thing that, which I would like to have myself, I hope you will get it.”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, undated letter [2] (after April 7, 1912). On several occasions he alerted them to exhibitions of modern French paintings: “I beseech you to go to the show at the rue de La Ville l’Evèque—and go back if you like it—; for among the Renoirs and Cezannes there are things out of collections that are very hard to see, and that I believe to be the greatest painting produced for a long time, and able to hold up its head in any company."Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, undated letter [2] (after April 7, 1912). His enthusiasms became a litany for the types of art that the Blisses would collect: “[S]ee the four great tapestries of hunting scenes ca. 1440, belonging to the Duke of Devonshire, now lent to S. Kensington. And Benson has some very lovely Chinese pots—clair-de-lune etc. And I was absolutely swept off my feet by the Astec [sic] masks in the British Museum, the most marvelous things ever existed; there is a limestone one which might just as well come from S. Denis ca. 1150. And Kelekian’s Persian pottery; and the Assur-Bani-Pal reliefs; and the English 11th cent. ivories."Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, February 7, 1913.

Historical and Artistic Networks

In 1911, the Public Record Office of the British Home Office appointed Royall Tyler editor of The Spanish Calendar of State Papers, a role that he assumed on the death of the previous editor, Martin Hume. The Spanish state papers contained the correspondence that the English monarchs received from Spain, and the Tylers spent considerable time in 1911 and 1912 transcribing and translating documents that were archived in Simancas, Vienna, and Paris. In 1914, Royall Tyler published volume nine (begun by Martin Hume), which contained the correspondence to Edward VI between 1547 and 1549, and volume ten, which completed the correspondence of the reign of Edward VI. In 1916, he published volume eleven, with the correspondence to Queen Mary in 1553. Apparently, Mildred Barnes Bliss read the first manuscript in draft and offered her opinion that historical documents had the ability to serve as a permanent guide to conduct.Elisina Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, August 18, 1913 [2]. This sentiment is reminiscent of the inscription the Blisses would install in 1940 at the entrance to the Byzantine Collection at Dumbarton Oaks: That the Continuity of Scholarship in the Byzantine and Medieval Humanities May Remain Unbroken to Clarify an Everchanging Present and to Inform the Future with Wisdom.

Royall Tyler's constant investigation of art brought him into contact not only with important dealers but also with influential museum curators. By 1912, he was on friendly terms with Sir Eric Maclagan, then keeper of sculpture and architecture at the South Kensington Museum (later the Victoria and Albert Museum) in London. Maclagan entered the South Kensington Museum in 1905, first in the textile department and later in the department of architecture and sculpture. He served as director from 1924 until his retirement in 1945. In 1912, Maclagan and the Tylers traveled together in Italy, visiting Udine, Civadale, and Venice, where they sought out important Byzantine artworks.Elisina Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, October 2, 1912. Royall Tyler wrote Mildred Barnes Bliss that “by travelling and seeing things with [Sir Eric Maclagan] I have been convinced that he is thoroughly competent.”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, January 4, 1913. By 1913, Royall Tyler knew Louis Metman, director of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, well enough to have him to lunch. Louis Metman had been instrumental in the creation of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. He became an assistant curator in 1892 and then head curator (conservateur) in 1899. Metman would be instrumental in providing the venue for Royall Tyler's ground-breaking exhibition on Byzantine art in 1931. And, by 1913, Tyler was friends with Matthew Stewart Prichard, “the only man alive who really knows and feels Byzantine art,”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, March 11, 1913. as Royall Tyler characterized him. Prichard had lived at Lewes, Sussex, with Edward Perry Warren (1850–1928), a Bostonian expatriate who was a collector of classical art and who secured many classical artworks for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.Edward Perry Warren (1860–1928), known as Ned Warren, was an American art collector and author. He received his bachelor of arts degree from Harvard College in 1883 and later studied at New College, Oxford, earning his master's degree in classics with a specific interest in classical archaeology. It was at New College that Warren met Matthew Stewart Prichard. Warren spent much of his time in Europe collecting art works, many of which he donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In 1902, he joined the museum as secretary to the director and was almost immediately promoted to assistant director. Although he played a major role in planning the present museum building, he was fired in July 1906. See Robert S. Nelson, Hagia Sophia, 1850–1950, Holy Wisdom Modern Movement (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 159–61. It was the Blisses, however, who may have introduced the Tylers to Gustave Schlumberger (1844–1929), a French historian and numismatist who specialized in the Crusades and the Byzantine Empire.Elisina Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, May 4, 1913.

In March 1913, the Tylers made an important art acquisition—a sixth-century Byzantine silver chalice,BZ.1955.18. which they obtained from the dealer Joseph Brummer in Paris.Elisina Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, May 4, 1913. According to Royall Tyler, “the joy of having the thing [left] no room for care.”Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, March 11, 1913. The Blisses lent the Tylers part or all of the purchase price of 28,000 francs, and the Tylers were grateful as they knew “nobody else who would have trusted [them] with so much money, or who possesse[d] so much, or who even believe[d] that so much money [might] exist together in one place.”Elisina Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, April 1, 1913. The acquisition of the chalice was followed at the end of the year by a joint purchase by the Blisses, who were at the time in the United States, and the Tylers of a treasure of Inca gold and silver objects from Joseph Brummer—“who but Brummer?,” as Royall Tyler remarked when he alerted the Blisses to this find. He continued in his announcement: “there is no shadow of doubt as to their authenticity. They are of a grand, sombre beauty that defies description, and of the utmost rarity—the British Museum itself cannot parallel them. Their cumulative effect—the colour of the gold—is uprooting. I hate advising anyone to buy without seeing, God knows, but I think it would be an ill turn not to advise you to buy now.”Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, December 3, 1913. At the bottom of this letter, in Mildred Barnes Bliss's hand, is the notation for a cablegram: “Yes blessings Dec 20 / Milrob,” the cable name of the Blisses. See PC.B.014, Ex.Coll.PC.B.467, PC.B.042, PC.B.444, PC.B.445, PC.B.469, PC.B.474, PC.B.475, PC.B.479, PC.B.480, PC.B.482, and PC.B.483. The price was also approximately 28,000 francs. The long-term effect of these two acquisitions was to redirect both the Tylers’ and the Blisses’ interests back to Byzantine art and, eventually, to Pre-Columbian art. In an important sense, the year 1913 should be seen as the inaugural date of the Blisses as serious art collectors.

War and Charity

The second half of the period covered by this correspondence coincides with World War I, which began with Germany’s declaration of war on France and Belgium in August 1914. When war broke out, the Tylers were at the Château de la Berchère near Nuits-Saint-Georges in Burgundy, which they had rented for the summer. They would leave in late October for London, where Royall Tyler had been engaged to catalogue a collection of historical documents.Elisina Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, September 30, 1914. Elisina Tyler had divorced Grant Richards in London on April 24, 1914, and the Tylers married in London on November 26, 1914. While they were in London, the expatriot American author Edith Wharton wrote Elisina Tyler: “[S]hortly after the war broke out, I rushed back here to plunge up to the chin in the managing of a work-room, which keeps me busy from dawn to dinner every day. . . . So you see we shall meet here instead of in England, after all—& I shall look forward to seeing you when you get back.”Edith Wharton to Elisina Tyler, October 11, 1914, Wharton mss., box 3, The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington. The Tylers returned to Paris in early 1915, and Elisina soon began working for Edith Wharton's charities.

At the beginning of the war, Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss, like many Americans living in France, became involved in private war relief charities. They were instrumental in the establishment of the American Distributing Service (Service de distribution américaine), the first American organization for hospital aid in France, which supplied hospitals with whatever they needed free of cost. See Ida Clyde Gallagher Clarke, American Women and the World War (New York and London: D. Appleton and Company, 1918), 477; and Dorothy McCardle, “A Red Rosette Emblems the Past For Mrs. Bliss,” Washington Post and Times Herald, January 30, 1966. Auxiliary to the American Distributing Service, the Blisses anonymously funded the purchase of an entire fleet of twenty-six ambulances for the Ambulance Field Service, later known as the American Field Service. Each ambulance had a plaque that read either “Aux Soldats de France, Deux Américains Reconnaissants” or “Offert aux défenseurs de la France par Deux Reconnaissants.”Bliss Papers, HUGFP 76.12, box 1. See also James W. D. Seymour, History of the American Field Service in France, “Friends of France”, 1914–1917 (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1920), 18 and 486. The Blisses also anonymously funded ambulances during World War II. See George Rock, The History of the American Field Service, 1920–1955 (New York: American Field Service, 1956). The Blisses would remain actively involved in the American Field Service even after it became an organization for foreign exchange students in 1947. Dorothy McCardle, “A Red Rosette Emblems the Past For Mrs. Bliss,” Washington Post and Times Herald, January 30, 1966.

Edith Wharton’s charity work initially involved founding a workroom (ouvroir) for out-of-work seamstresses and secretaries and eventually enlarging on that model to establish the American Hostels for Refugees (Accueil franco-américain aux réfugiés belges et français) in collaboration with the Foyer franco-belge, another private organization, in November 1914. The hostels grew in number and responsibility, and Edith Wharton asked Elisina Tyler to serve as the organization’s vice president in 1915. Together, they established lodging houses throughout France that cared for French, Belgian, and Alsatian women and children left destitute by the war. The American Hostels for Refugees maintained three large lodging houses, two restaurants that served over six hundred meals a day, an employment agency, a large workroom for women, a day nursery, a free clinic with a dispensary, and depots for donations of clothing, coal, and groceries. An outgrowth of the hostels was the establishment of two hospitals with one hundred beds each at Groslay (near Paris), another lodging house in Paris, and a hospital for anemic and tubercular children at Arromanches in Normandy. Mildred Barnes Bliss was an active supporter of the American Hostels for Refugees. See Alan Price, The End of the Age of Innocence: Edith Wharton and the First World War (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 29–30.

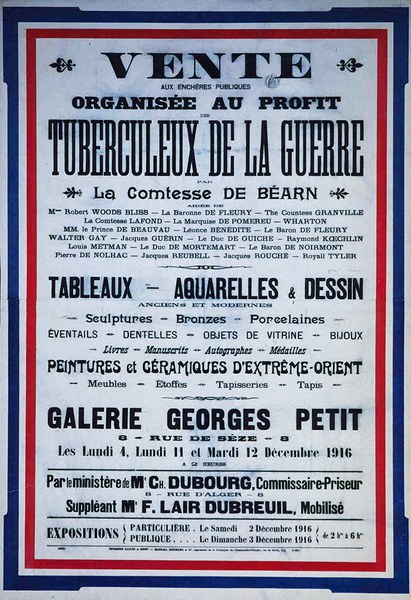

Enlarging again on the ouvroir model at the request of the Belgian government, Edith Wharton founded the Children of Flanders Rescue Committee (Oeuvre des enfants des Flandres), with Elisina Tyler as its director, in April 1915. The committee cared for the children of the bombarded towns of western Flanders and, in particular, created schools where lacemaking was taught to the older girls according to the methods of the École Normale of Bruges. In 1916, Edith Wharton and Elisina Tyler helped in the formation of the Comité d’oeuvre d'assistance aux tuberculeux de la guerre, one of the earliest organizations to undertake the fight against tuberculosis in France, offering a cure program for soldiers, women, and children. Mildred Barnes Bliss undertook similar responsibilities as vice president of the Comité franco-américain pour la protection des enfants de la frontière (French-American Committee for the Protection of Frontier Children), an organization founded by Frederic R. Coudert in August 1914 to rescue refugee children from the invaded region in the north of France and bring them to Paris. The Comité franco-américain eventually established over twenty-five colonies throughout France. See Ida Clyde Gallagher Clarke, American Women and the World War (New York and London: D. Appleton and Company, 1918), 473–74; and “Rescuing Children from War-Torn Alsace; Frederic R. Coudert and Other Americans Aid in Caring for Little Ones Separated from Parents in Territory Invaded by Germans,” New York Times, February 7, 1915. See also Edith Wharton, “My Work Among the Women Workers of Paris; Noted American Novelist Tells How Her Ouvroir Gave Support to an Army of Women Left Without Employment by the War,” New York Times, November 28, 1915. Mildred Barnes Bliss also served on the Polish University Grants Committee of the Polish Victims’ Relief Fund, an organization begun in the spring of 1916 by Jane Arctowska to aid Polish refugee intellectuals who lacked a means of livelihood due to the war. See Ida Clyde Gallagher Clarke, American Women and the World War (New York and London: D. Appleton and Company, 1918), 501–2. Similarly, Robert Woods Bliss was an anonymous sponsor of the Fund for Russian Refugees in Paris.Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, February 26, 1916. In 1918, Mildred Barnes Bliss served on the Committee for Men Blinded in Battle, which sought funds to support blinded soldiers. See “Pershing to Help Blind; General Will Serve on Committee with Miss Winifred Holt,” New York Times, June 16, 1918.

In a letter to her parents, Mildred Barnes Bliss recounted the efforts underway in December 1916 to provide Christmas celebrations for the various charities that she supported: “I am shaking down again and frantically Christmasing . . . for the fifty Frontier kiddies and the personnel; the Distributing Service and personnel; the Franco-American colleagues and personnel; our Ambulance Section of 22 Americans and 9 French; the Hospital at Nevers and 2500 Zouaves! The latter I am halving with Carolyn and we send 250 geese and puddings. Every child in the oeuvre (Fr. Am. Frontier Children) is to receive 2 francs worth of surprise, but we have pooled the contributions and I’m doing no work.”Mildred Barnes Bliss to Anna Barnes Bliss and William Henry Bliss, December 8, 1916, Blissiana files, William Henry Bliss correspondence. But the frenzy and stress of relief work occasionally led to friction, and this was especially true between Mildred Barnes Bliss and Edith Wharton. Wharton had long believed that Mildred Barnes Bliss was determined to keep American funding from going to her charities. In a letter to Elisina Tyler, Wharton wrote: “I am not given to supposing that people dislike me, or that any one wd take the trouble to ‘me faire un tort’ for the pleasure of it; but long before you were willing to admit it I knew that Mildred was at work doing her utmost to undermine my credit with the Rockefeller Commission. I have found out that every one of their successive wise-acres went home with the recommendation ‘not to get mixed up with any of Mrs. Wharton’s work,’ & that Dr. Biggs told the Commission that they had better not be associated with us in any way, as we were a ‘party organisation' & 'in opposition to the French government.’”Edith Wharton to Elisina Tyler, August 5, 1916, Wharton mss., box 3, The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Aware of the problems between Mildred Barnes Bliss and Edith Wharton, Elisina Tyler wrote three revealing letters to Royall Tyler hinting at the rift. In the first, she stated: “Also, I confess I have had corroborative tales of Edith's incredible ruthlessness and lack of consideration for Mildred and Robert.”Elisina Tyler to Royall Tyler, March 29, 1917, Wharton mss., box 3, The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington. In a second, she observed: “Edith . . . is again most awfully cross with Mildred about something which it would be too long to explain.” According to Elisina, Wharton had said, “I seem to poison her after I’ve been with her half an hour and she gets perfectly horrid.”Elisina Tyler to Royall Tyler, July 22, 1917, Wharton mss., box 3, The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington. In a third, she reported: “Mildred said to me that Edith was ruthless and autocratic, never worked with her committees and only let people slave away for her, and then was quite ready to give the credit for the work to any new person who seemed to tickle her fancy. No one would ever work long for anything with which she was connected, she said, except me, because of what she called my splendid loyalty, because Edith succeeded in disgusting people, even the best.”Elisina Tyler to Royall Tyler, July 31, 1917, Wharton mss., William Royall Tyler files, folder 9, The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Casa Dorinda, Antigny-le-Château, and the Pavillon Colombe

In April 1916, the Blisses’ parents began planning a new house that they would build in Montecito, California, near Santa Barbara. They would name the house Casa Dorinda, using Anna Barnes Bliss's middle name. William Henry Bliss enthusiastically wrote Robert Woods Bliss: “[W]e bought yesterday a 16 acre lot here, between the sea and mountains, covered with live oaks, lemon, and countless other trees and shrubs, and roses galore, and we’re going to build this summer either a bungalow or Spanish house, big enough to house you and M[ildred] when you come over next year, (Charles and A[nnie] L[ou] too) in luxurious space and comfort, while you are building, and planting your own vine and fig leaf, which you will surely begin doing after you have been here a week. Your quarters are to be embowered in yellow rose trees, A[nnie] L[ou]’s in pink.”William Henry Bliss to Robert Woods Bliss, April 29, 1916, Blissiana files, William Henry Bliss correspondence. By February 1917, the Spanish-style house was nearing completion, and the Los Angeles Times remarked: “Probably the finest residence in the Spanish style that has been built in California for some years is now under construction at Montecito, Santa Barbara county, for Mr. and Mrs. William H. Bliss.” “Spanish Architecture Glorified in Mansion; New Gem Among Homes in California,” Los Angeles Times, February 5, 1917. The house was designed by Carleton Winslow, who had designed buildings for the 1915 Exposition in San Francisco. Designed in Spanish Mission style, the house had more than eighty rooms that surrounded a central patio. The house was completed in 1918.

On September 12, 1916, Elisina Tyler's son, Gerard Richards, was accidentally killed by the collapse of a tunnel of sand in which he was playing on a beach in Cornwall. See Alan Price, The End of the Age of Innocence: Edith Wharton and the First World War (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 98–99. After Elisina Tyler returned from the funeral in England, the Blisses visited the Tylers in Burgundy at the Château de Genay, a property that the Tylers frequently rented during the war years. During the week they spent there, the Blisses and Tylers traveled through Burgundy to break “the dreary routine for her, just after Gerard was killed,” as Mildred Barnes Bliss explained to her stepfather. She reported that they “ambled about to see every ‘rotting tower’ and reveled in the wines,” and that they were struck by the “architectural beauty of the past in mellowed Burgundy, untouched by the horror of the present,” the “finest Cistercian abbeys . . . mediaeval castles used as farms, and the fine churches,” as well as “the flavor of Burgundian hospitality.”Mildred Barnes Bliss to William Henry Bliss, December 8, 1916, Blissiana files, William Henry Bliss correspondence. One outcome of the trip was their visit to the medieval Antigny-le-Château, which the Tylers later acquired as their primary residence in 1923. See Elisina Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, December 1, 1913; and Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, October 22, 1916. The Tylers’ son, William Royall Tyler, who was six at the time, later recalled the Blisses’ visit: “In 1916, Mr. and Mrs. Bliss came to stay, and I was awed by her: a vision of elegance and mystery, with furs, a large hat, long gloves and exotic perfume, who swooped down on me and asked me if I would like to see her do a fox trot. Confused by this abracadabra, I merely hung my head, whereupon the vision turned on its heels and started taking short jerky steps with little turns around the room, holding its arms half extended before it. I suffered extreme discomfort and embarrassment from all this, but the present of a silver pen-knife, my first, restored my composure.”Typescript, 199. See also Elisina Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, October 23, 1916.

Perhaps as a consequence of her son’s death, Elisina Tyler began to suffer from a nervous condition in 1917. That winter, Mildred Barnes Bliss arranged for her to stay at a resort at Beauvallon sur Mer, known for having one of the warmest winter climates in France.Elisina Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, April 9, 1917. During her convalescence at Beauvallon, Royall Tyler and Edith Wharton traveled to Fontainebleau, and “[o]n the way back we saw a little Louis XVI which is perfectly lovely, with the most charming park and every sort of charm. Edith very wisely is not going to speak of it to anyone until she has either bought it or announced, and she is seriously thinking about it. There are fine and very valuable tapestries in the house.”Royall Tyler to Elisina Tyler, March 19, 1917, Wharton mss., William Royall Tyler files, folder 9, The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington. This was the Pavillon Colombe, then named the Villa Jean-Marie, which Edith Wharton would acquire in 1919. In September 1917, Elisina's doctors recommended that she undertake a complete rest cure in Aix-en-Provence.

America at War and the Peace Treaty

When America entered the war in 1917, Royall Tyler joined the army and was commissioned as a lieutenant and assigned to the G-2 section for German prisoner of war interrogation. He rose to the rank of major by the end of the war.See essay the military service of Royall Tyler. During this period, he met Hayford Peirce, his future collaborator on Byzantine art publications, who had been assigned to his office headquarters at the Hôtel Crillon. America’s involvement in the war also meant that most of the work of the American-established private charities was taken over by the American Red Cross, much to the dismay of Edith Wharton among others.Mildred Barnes Bliss, as a diplomat’s wife, was naturally supportive of the American Red Cross in France while Edith Wharton, having labored to build up private refugee relief and medical care institutions, felt understandably disenfranchised. Wharton believed that Mildred Barnes Bliss had sided with the Red Cross, and Elisina Tyler wrote to Royall, “I told her all I knew of the report working against her with the Red Cross and assured her that I was morally certain it had not originated with Mildred alone.” Elisina Tyler to Royall Tyler, August 2, 1917, Wharton mss., William Royall Tyler files, folder 9, The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington. Since the American embassy would now play a greater role in the war relief efforts, the Red Cross established the Woman's War Relief Corps in France in the fall of 1917. The corps was placed under the direction of Mrs. William P. Sharp, the wife of the American ambassador, and was managed by an executive board chaired by Mildred Barnes Bliss and on which Edith Wharton served. The responsibilities of the corps were organized into fourteen divisions: Blind; Canteens; Diet Kitchens; Equipment; General Information and Reclamation Bureau; Hospital Auxiliary Service; Nurses (Auxiliary); Nurses (Trained); Propaganda and Records; Refugees (Adults, Children); Registration; Social Service; Surgical Dressings; and Workrooms and Ouvroirs.

In 1918, Robert Woods Bliss was temporarily assigned to serve as chargé d’affaires at the U.S. legation in The Hague. For their services during the war, the Blisses, the Tylers, and Edith Wharton were all given various honors, including being made chevaliers in the French Légion d’honneur. Mildred Barnes Bliss received the Medaille d’honneur en Or in 1915, and in September 1918, the Belgian government awarded Edith Wharton and Elisina Tyler the Medal of Queen Elisabeth for their refugee work. After the war, the Belgian government named Edith Wharton a chevalier of the Order of Leopold, the Belgian equivalent of the French Légion d’honneur. And on November 25, 1920, at a public session of the French Academy, Raymond Poincaré awarded Edith Wharton and Elisina Tyler jointly a gold medal of the Prix de Vertu. In her autobiography, Edith Wharton recalled Elisina Tyler's service: “Never once did she fail me for an hour, never did we disagree, never did her energy flag or her discernment and promptness of action grow less through those weary years.” Edith Wharton, A Backward Glance, An Autobiography (New York and London: D. Appleton-Century, 1934), 348–49. Much of that energy had been spent in fundraising to support the charities, and this also continued after the armistice. In April 1919, Elisina Tyler traveled to New York City in order to attempt to keep American support from waning now that the war had ended. “Edith Wharton’s Work in France; Her Representative Comes to America and Tells of Saving Tuberculous Women and Children,” New York Times, April 13, 1919. In 1919, Royall Tyler and Hayford Peirce became members of the U.S. delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, and in 1920, Tyler was appointed to a four-year term on the U.S. delegation of the Reparation Commission (Commission des réparations des obligations de l’Allemagne).

In September 1919, the Blisses left Paris to move to Washington, D.C. Robert Woods Bliss was to become chief of the Division of Western European Affairs at the Department of State. In that capacity, he would be in charge of protocol and ceremonies during the 1921 Washington Conference on the Limitation of Armaments. Simultaneously, he served as chairman of the diplomatic service board of examiners. After arriving in New York City in October, Mildred Barnes Bliss wrote her social secretary, May Amboul, in Paris: “[Robert Woods Bliss] has been given a new and most interesting job, which he will not take over until February, and which will not be made public until his successor in Paris can be appointed. . . . We have taken a flat in Washington, funnily enough in the same building where my parents lived one year, and as my mother has kindly loaned us a good deal of her furniture, and has been an angel of kindness in moving it into the flat for us, we shan’t have to bring out much from Paris.”Bliss Papers, HUGFP 76.8, box 21. The apartment was at 1786 Massachusetts Avenue, now the headquarters of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.