The Folger Shakespeare Library

The Folgers’ love of the bard led them to acquire Shakespeareana at a breakneck pace, eventually building the world’s premiere collection.

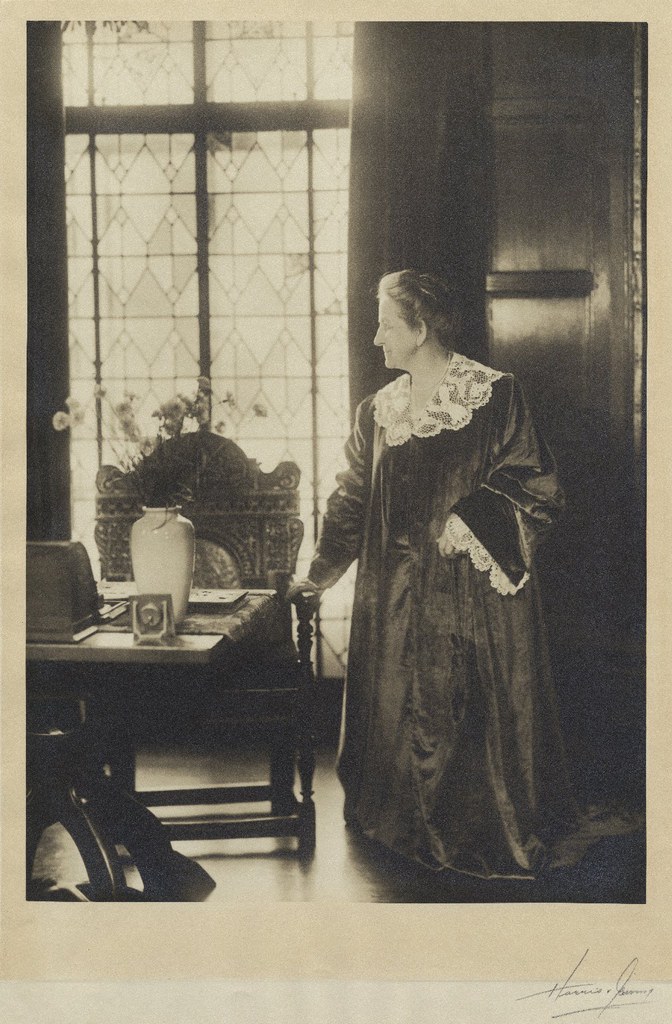

Henry and Emily Folger loved each other, but had no children. They channeled their energies into their love of Shakespeare instead.

Stephen H. Grant

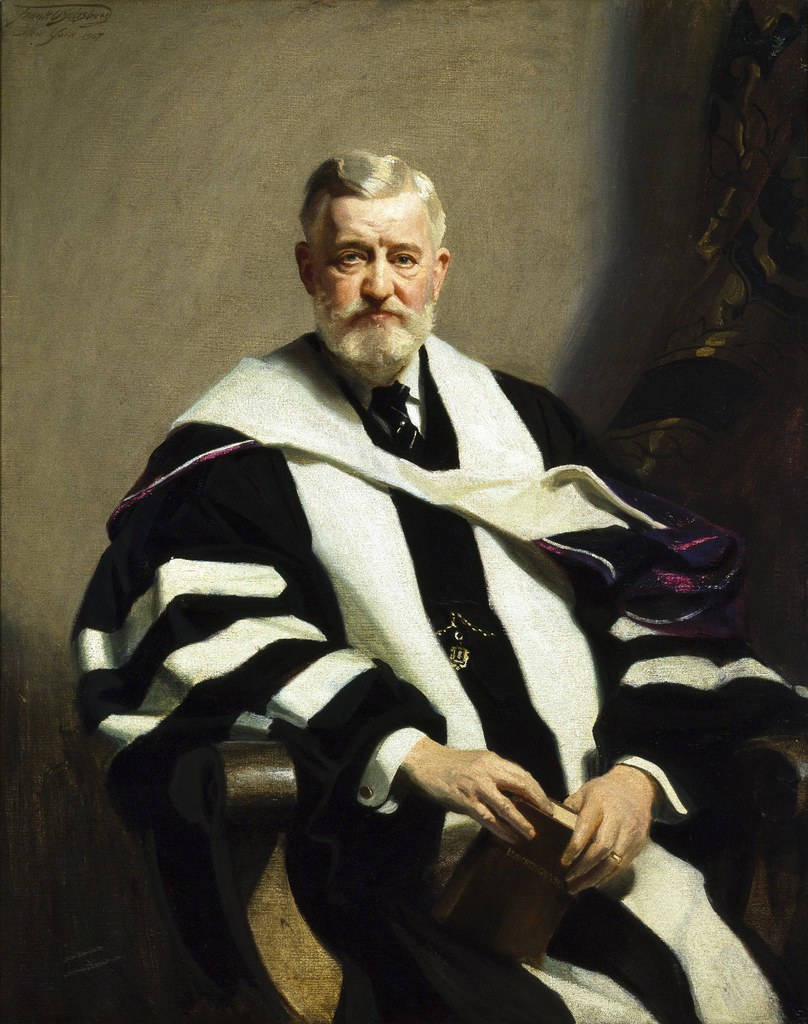

Henry Clay Folger Jr. (1857–1930) was born to upper-middle-class parents in New York and attended Amherst College, where he developed his love for Shakespeare’s plays. Emily Jordan Folger (1858–1936), who hailed from Ironton, Ohio, studied languages and literature at Vassar College.Dorothy E. Mason, Elaine Fowler, and Philip Knachel, “The Folger Shakespeare Library and Washington, D.C.: A Brief History,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 69–70 (1969): 346–70 and Stephen H. Grant, Collecting Shakespeare: The Story of Henry and Emily Folger (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014), 10. Find out more about the Folger Shakespeare Library on its website, http://www.folger.edu/, and discover their collections at http://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/FOLGERCM1~6~6. Three years after graduation, Henry's roommate, Charles Pratt, introduced Henry and Emily at an Irving Literary Circle of Brooklyn picnic on Sands Point, Long Island Sound on June 7, 1882.Stephen H. Grant, “A Most Interesting and Attractive Problem: Creating Washington’s Folger Shakespeare Library,” Washington History 24, no. 1 (2012): 2. That year also marked the first time Henry began his “commonplace books,” notebooks in which he jotted down the English and American literature passages, quotations, and references that he found striking.Grant, Collecting Shakespeare, 30. Three years later, on October 6, 1885, Emily and Henry married in the Westminster Presbyterian Church in Elizabeth, New Jersey.

Emily earned a master’s degree in English from Vassar in 1896. Leading Shakespeare scholar Horace Howard Furness advised her senior thesis on Shakespeare.Andrea Mays, The Millionaire and the Bard (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015): 95–96. During these years, Henry worked for prominent oil companies, including Standard Oil and Pratt Oil, rising through the ranks from chairman of the manufacturing committee to assistant manager, ultimately becoming president of the incorporated Standard Oil Company of New York.

Amassing the Collection

The Folgers followed their passion for Shakespeare and developed a meticulous, compulsive process for acquiring folios, books, and other pieces. Henry and Emily proved an unstoppable pair: he would locate the item he desired, and she would “hunt up bibliographical details and investigate difficult allusions, and . . . advise him to purchase a book or manuscript when he was wavering and undecided.”A. S. W. Rosenbach, Henry C. Folger as a Collector (New Haven, Conn., 1931), 31.

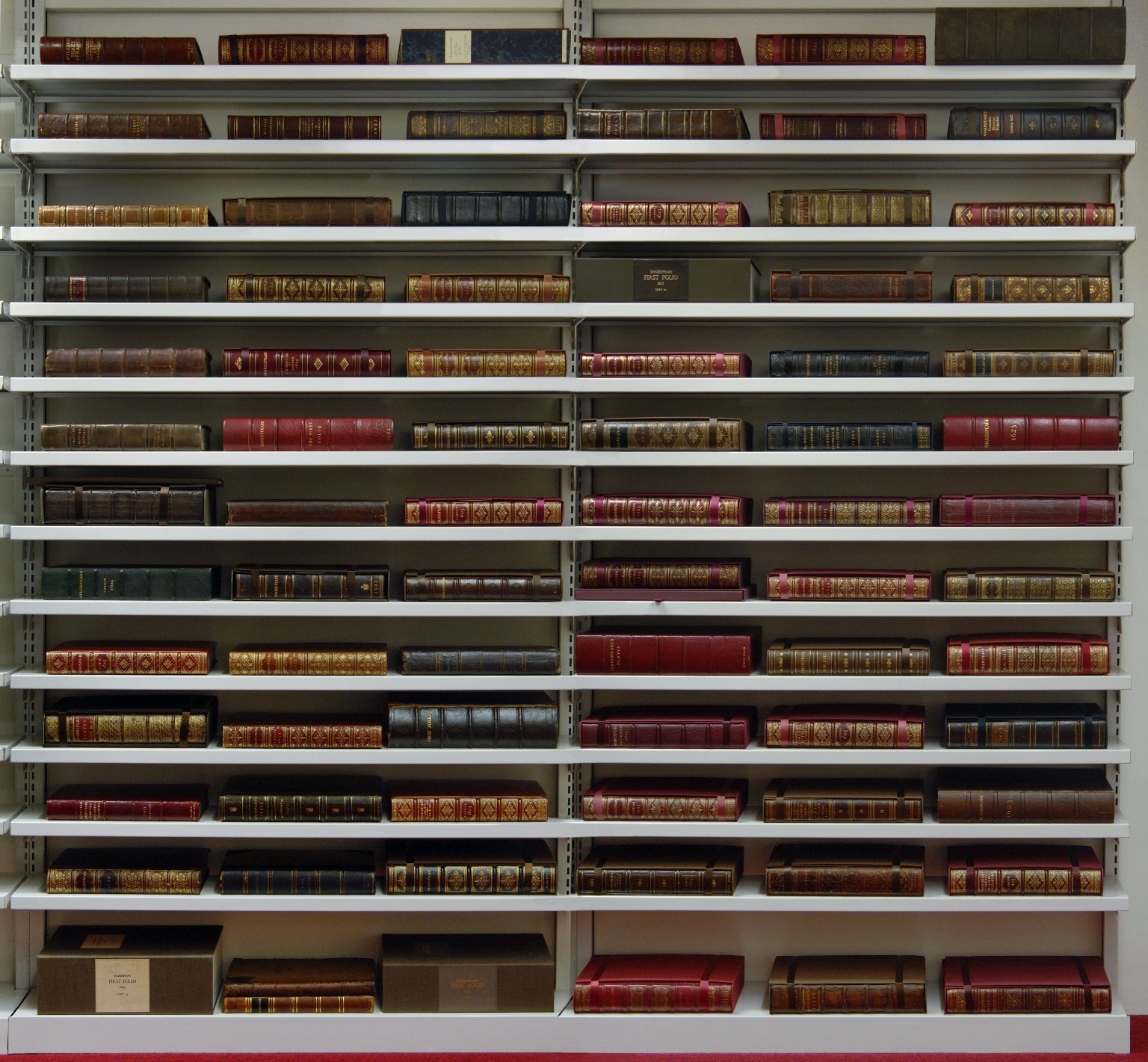

Over decades, the Folgers amassed an extensive collection of Shakespeareana, including “books, manuscripts, pamphlets, newspapers, playbills, scrapbooks, public documents, diaries, phonographic records, engravings, oil paintings, drawings, carvings, building models, ceramics, and much more.” The Folgers acquired, on average, six books a day for a period of over forty years, and the library included over ninety thousand volumes when it opened in 1932.Grant, “A Most Interesting and Attractive Problem,” 7. “It was monotonous, doubtless, to the staid collectors and booksellers who were used to the game, but to young Folger it was the most exciting moment of his life,” art dealer A. S. W. Rosenbach wrote about the relentless pace of collecting.Rosenbach, Folger as a Collector, 2.

Each of the Folgers’ acquisitions had a backstory. In 1899, for example, Henry set out to purchase the Augustine Vincent First Folio from its owner, Coningsby Sibthorp. After four years of back-and-forth bargaining and miscommunication, the Folgers, in 1903, successfully purchased the text for £10,000, the highest price ever paid for a book at the time.Mays, Millionaire, 140. The Folgers were very secretive about their collection, and the Vincent First Folio was the only work about which Henry Folger ever wrote, publishing an essay in The Outlook in November 1907.

Building the Library

In 1910, Henry decided he wanted to curate his collection for Shakespeare scholars. He envisioned a space—unlike a public library or museum—for a couple of true Shakespeare lovers to use at a time, and he shifted his collecting efforts to match this mission. The Folgers slowed their pursuit of the most expensive volumes in order to redirect their resources to purchasing land and paying for construction.Mays, Millionaire, 250.

The Folgers considered several locations for the library before ultimately choosing Washington, D.C. “I finally concluded I would give it to Washington; for I am an American," Henry said, emphasizing his patriotism and desire for a “national” collection.Grant, “A Most Interesting and Attractive Problem,” 7, 9.

For nine years, the Folgers eyed a string of properties on a block of land around the Capitol, 760 East Capitol Street between 2nd and 3rd Streets SE. When they found out that the Library of Congress had made plans to expand there, the Folgers worked with Congress to secure the rights to the land in 1928, using personal connections with the Library of Congress to exempt their parcel of land.

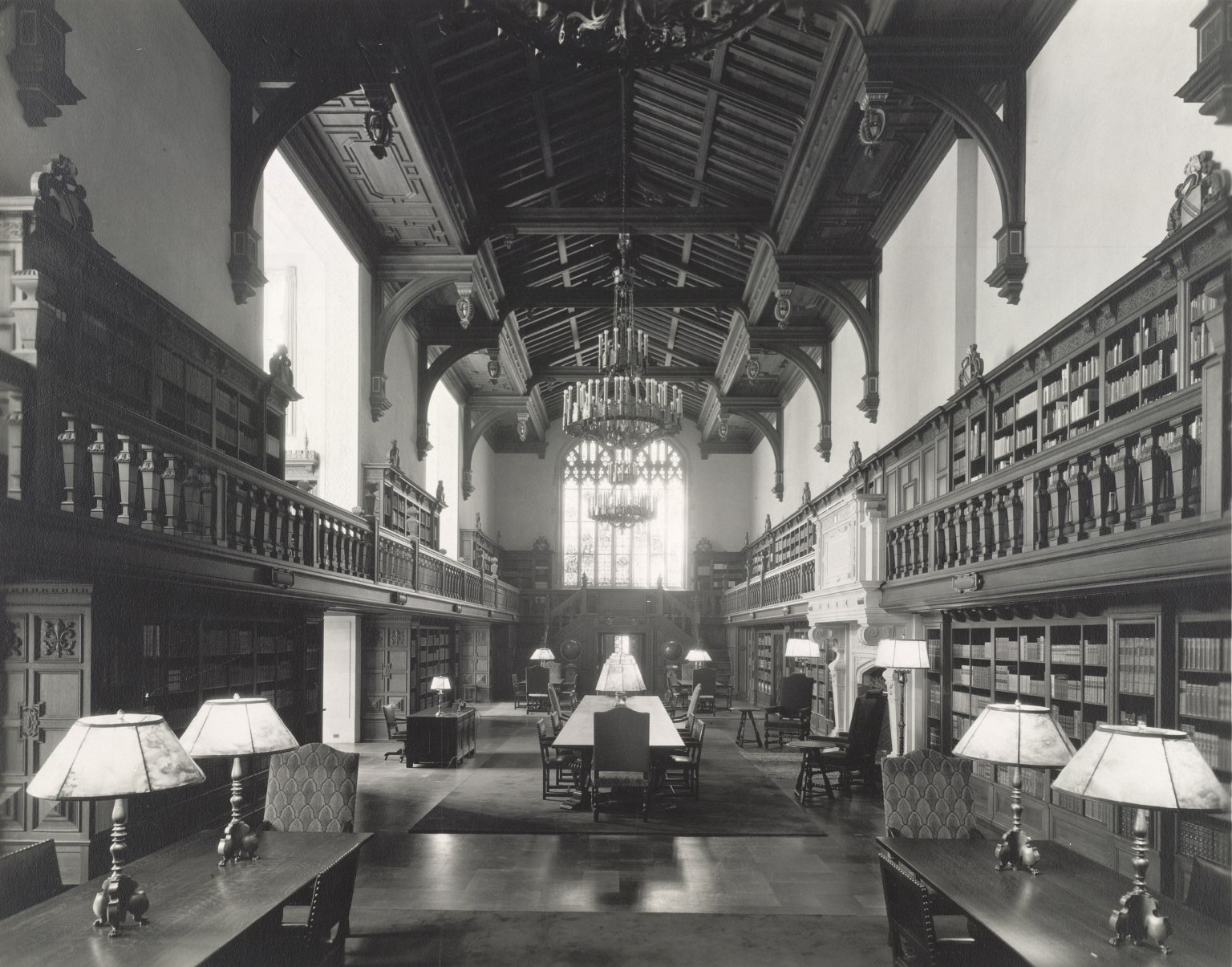

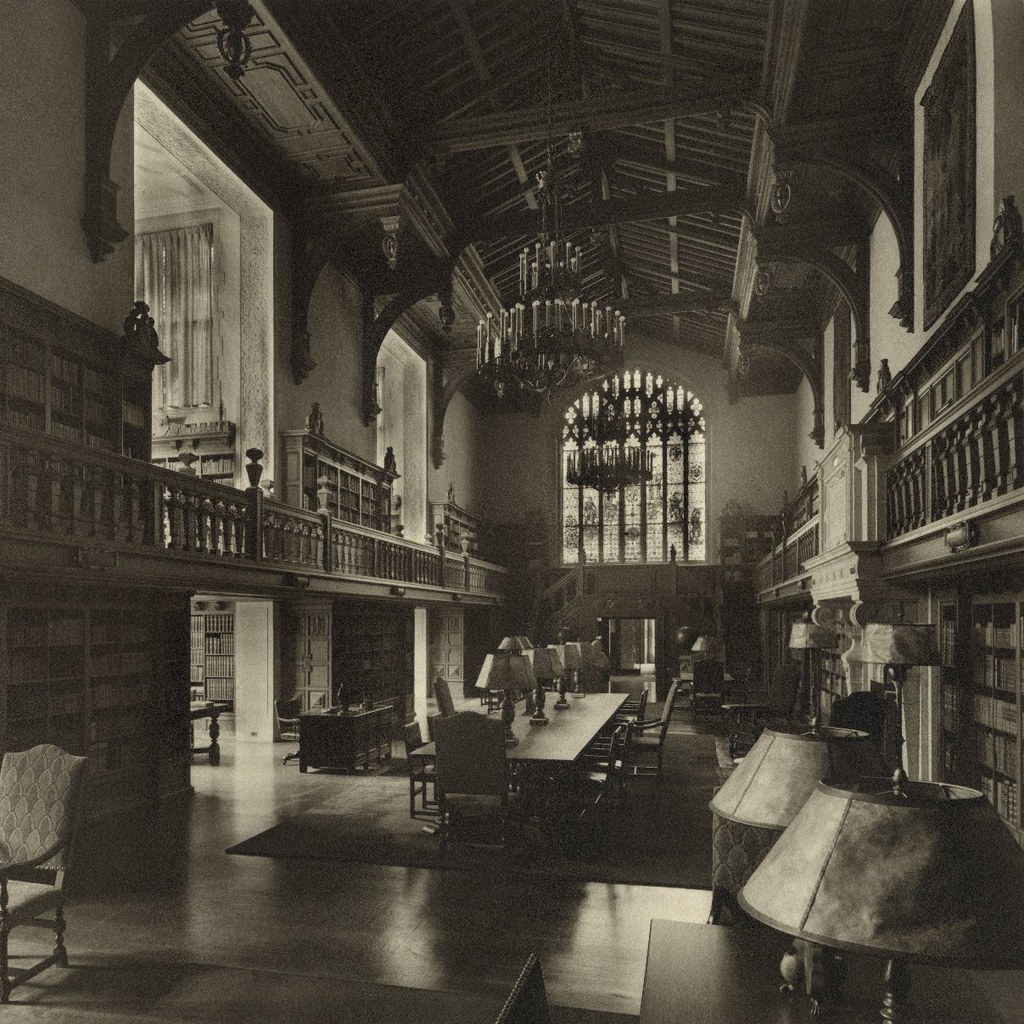

Often touted “the world's greatest monument to Shakespeare,” the marble building featured depictions of scenes from Shakespeare’s plays and a Tudor-style interior, complete with high ceilings, wooden beams, stained glass windows, and, of course, over twenty thousand books and eighteen thousand manuscripts.Wanda Reif, “Shakespeare's Home on Capitol Hill,” The Lancet 360, no. 9337 (2002).

Expansion

Henry Folger did not survive to see his dream come to fruition: he died suddenly from a pulmonary embolism on June 11, 1930, two years before the library’s formal dedication, in April 1932. Emily died soon thereafter, in 1936. The Folger Library’s future was in the hands of its directors and patrons.

The Folger Shakespeare Library continued to grow and expand, under new directors and their initiatives. In 1935, the library’s board of trustees established annual fellowships for Shakespeare scholars. Two years later, in 1937, the library acquired the library of Sir Leicester Harmsworth, an English antiquarian. Composed of more than nine thousand volumes published between 1475 and 1640, the Harmsworth collection transformed the Folger Shakespeare Library into one the largest collections of its kind in the world, rivaled only by the Huntington Library in Los Angeles, California, the Bodleian at Oxford University, and the British Museum.

The library continued to operate during the Second World War, but administrators relocated thirty thousand of the museum’s rarest and most valuable volumes to Amherst College for safekeeping.Stanley King, Recollections of the Folger Shakespeare Library (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1950), 39.

Institutional Governance

In line with his exacting collection practices, Henry laid precise groundwork for the governance of his institution. A board of trustees, under the auspices of Amherst College, and museum directors would determine who could study in the Reading Room, which volumes to purchase, and which exhibitions to launch.

Henry, however, kept his plan a secret from everyone but his wife, and the trustees of Amherst College, who were to administer the collection, learned of this only after the terms of Folger’s will were published in newspapers.Mason, Fowler, and Knachel, “Folger Shakespeare Library,” 350. The Massachusetts Legislature had to amend the Amherst College charter in order to meet Henry’s requests.King, Recollections, 13.

For the first decade of its existence, the Folger Shakespeare Library operated under the direction of two, effectively equal, codirectors: Joseph Quincy Adams, previously an English professor at Cornell, and William A. Slade, who had worked for the Library of Congress. Adams supervised scholarship at the library, and Slade focused on the administrative aspects of its day-to-day operations. (Stanley King, president of Amherst College from 1932 to 1946, recalled that Emily advocated for a third director, who would “devote his time when he joined the staff of the Folger Library to the improvement of the speech of the people of the United States,” but that the trustees ultimately did not create this position.)King, Recollections, 10. Adams sought to expand and catalogue the Folgers’ personal collection and to prevent duplication between the Folger and the Library of Congress.Mason, Fowler, and Knachel, “Folger Shakespeare Library,” 356 and King, Recollections, 42.

Profile by Melda Gurakar, Melissa Rodman, Joy Wang, and Leah Yared, 2016 summer interns.