Transcript

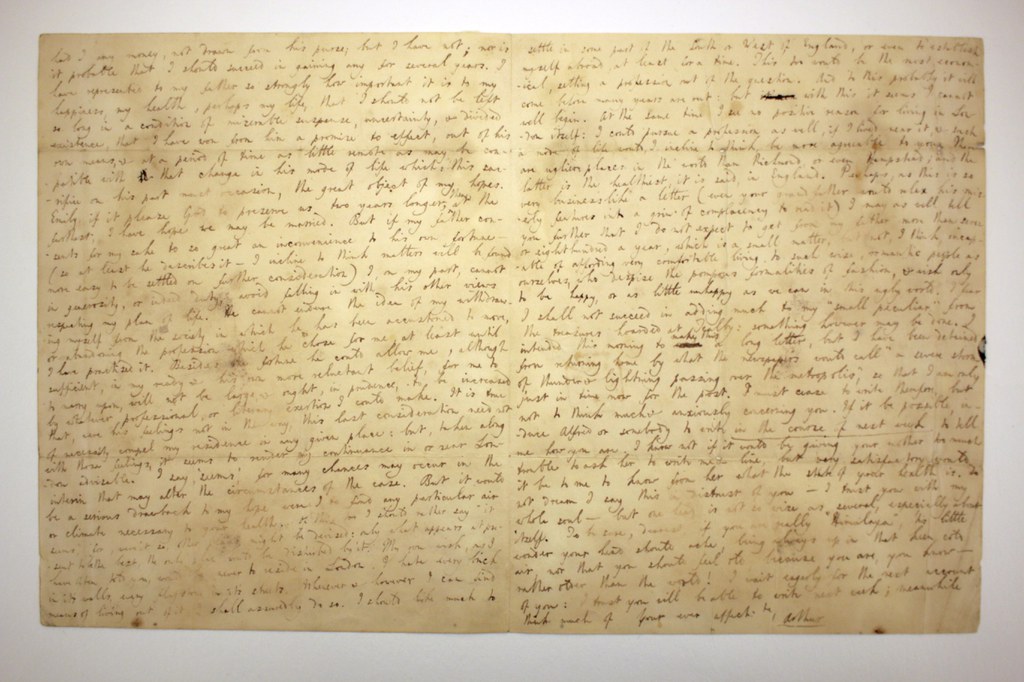

[Sat. June 9, 1832]

Miss Emily Tennyson

Somersby Rectory

Spilsby

Lincolnshire

My own dearest creature, I fear you have been much more seriously unwell than I allowed myself to think you were, or even than you now confess. I would I knew what to say or do for you. For God’s sake do not leave me in ignorance of any change that occurs in your health: I cannot make out from what you now say what kind of illness you have had, whether an aggravation of your constant annoyances, or something quite new & distinct. Charles spoke of “epidemic cold”, but a word of that sort means anything. Tell me truly, have you only suffered what others in the family have suffered, or is your former complaint made worse? I am sure I do not want to torment you by frequent questioning, nor have I done it lately: but I cannot read your mournful words, “I am still very weak and unwell”, without great anxiety, & a desire to know more about you. Have you been under Dr. Bonstulo’s care? What does he tell you? I am determined, when next I come to Somersby, to see him, & learn from him his real opinion. I am particularly anxious to ascertain whether climate & air affect your general health. You told me, I think, yourself, that you had no reason to suppose it did, except that you were always better in warm weather. Now I will tell you why I am anxious on this point. You are well aware, dearest Emily, that my prospect of attaining the only earthly happiness possible for me, my union with yourself, depends entirely on my father’s will. It would not depend at all on his will had I any money, not drawn from his purse; but I have not; nor is it probable that I should succeed in gaining any for several years. I have represented to my father so strongly how important it is to my happiness, my health, perhaps my life, that I should not be left so long in a condition of miserable suspense, uncertainty, & divided existence, that I have won from him a promise to effect, out of his own means, & at a period of time as little remote as may be compatible with his“his” is stricken out. that change in his mode of life which this sacrifice on his part must occasion, the great object of my hopes. Emily, if it please God to preserve us two years longer, then at the furthest, I have hope we may be married. But if my father consents for my sake to so great an inconvenience to his own fortune—(so at least he describes it—I incline to think matters will be found more easy to be settled on further consideration) I, for my part, cannot in generosity, or indeed duty, avoid falling in with his other views respecting my plan of life. He cannot endure the idea of my withdrawing myself from the society in which he has been accustomed to move, or abandoning the profession which he chose for me, at least until I have practiced it. Besides, the fortune he could allow me, although sufficient, in my ready & his own more reluctant belief, for me to marry upon, will not be large, & ought, in prudence, to be increased by whatever professional, or literary exertion I could make. It is true that, were his feelings not in the way, this last consideration need not of necessity compel my residence in any given place: but taken along with these feelings, it seems to render my continuance in or near London advisable. I say, “seems”, for many chances may occur in the interim that may alter the circumstances of the case. But it would be a serious drawback to my hope were I to find any particular air or climate necessary to your health. Of this too I should rather say “it seems”, for, were it so, other plans might be devised: only what appears at present to be the best, the only plan, would be disturbed by it. My own wish, as I have often told you, would be never to reside in London. I hate every brick in its walls, every flagstone in it’s [sic] streets. Whenever & however I can find means of living out of it, I shall assuredly do so. I should like much to settle in some part of the South or West of England, or even to establish myself abroad, at least for a time. This too would be the most economical, setting a profession out of the question. And to this probably it will come before many years are out: but it se“it se” is stricken out. with this it seems I cannot well begin. At the same time I see no positive reason for living in London itself: I could pursue a profession as well, if I lived near it, & such a mode of life would, I incline to think, be more agreeable to you. There are uglier places in the world than Richmond, or even Hampstead; and the latter is the healthiest, it is said, in England. Perhaps, as this is so very businesslike a letter (even your grandfather would relax his miserly features into a grin of complacency to read it) I may as well tell you further that I do not expect to get from my father more than seven or eight hundred a year, which is a small matter, but not, I think, incapable of affording very comfortable living to such wise, romantic people as ourselves, who despise the pompous formalities of fashion, & wish only to be happy, or as little unhappy as we can in this ugly world. I fear I shall not succeed in adding much to my “small peculiar” from the treasures hoarded at Tealby: something however may be done. I intended this morning to write“write” is stricken out. make this a long letter, but I have been detained from returning home by what the newspapers would call “a severe storm of thunder & lightning passing over the metropolis”, so that I am only just in time now for the post. I must cease to write therefore, but not to think much & anxiously concerning you. If it be possible, induce Alfred or somebody to write in the course of the next week to tell me how you are. I know not if it would be giving your mother too much trouble to ask her to write me a line, but very satisfactory would it be to me to know from her what the state of your health is. Do not dream I say this in distrust of you—I trust you with my whole soul—but one head is not as wise as several, especially about itself. To be sure, dearest, if you are really “Himalaya”, ‘tis little wonder your head should ache, being always up in that keen, cold air, nor that you should feel old, because you are, you know—rather older than the world! I wait eagerly for the next account of you: I trust you will be able to write next week; meantime think much of Your ever affectionate

Arthur

Commentary

Arthur Henry Hallam would be obscure to us today if his death at the age of twenty-two had not been immortalized in the grief-stricken words of Alfred Tennyson, his closest friend. Emily Tennyson, the poet’s sister, was Hallam’s fiancée; this letter captures a relatively late stage in their relationship. Hallam and Tennyson had become friends at Trinity College, Cambridge, where the former matriculated in 1828; in spring 1830, between the Lent and Easter terms of his second year, Tennyson invited his friend to his family home in Spilsby, Lincolnshire, for three weeks. Hallam quickly fell in love with Emily Tennyson, and by early 1831 was referring to her in verse as “my promised wife.” Both fathers of the young couple disapproved of the early connection and forbade further visits to Somersby until Hallam came of age in February 1832. He took his degree early that year and, immediately after entering the Inner Temple in accordance with his father’s wishes, decamped for Somersby at the end of the month for a five-week stay.

This letter comes from about three months after the end of that visit. Hallam’s biographer, Martin Blocksidge, writes that the couple established a rhythm in which Emily would write one letter a week for arrival on Saturday; Hallam would then reply by return post. Hallam’s worrying about Emily here—the better part of his twelve-hundred-word letter is spent asking after her health—may seem excessive and badgering, but the entire Tennyson family had a tendency toward hypochondria, and Emily had a habit of being vague about her health. In some sense, the letter shows Hallam at his worst: needy, gushing, and a little overbearing. After spending a page worrying about her health, explaining how marrying her is “the only earthly happiness possible for me,” he adds nonchalantly, “but it would be a serious drawback to my hope were I to find any particular air or climate necessary to your health.” Other letters show them in better moods and happier spirits; this letter unfortunately catches Hallam on a bad day.

It offers a fascinating look into its author’s prospects, however, and the barriers that might stand in front of marriage for a couple of equal age and little independent income. Hallam realizes that his marriageability is dependent on how large an allowance his father is willing to give him. Henry Hallam disapproved of the relationship and worried that his son was ruining his chances by rushing into marriage with Emily; there was also a note of snobbery in his treatment of the Tennysons, children of an irate provincial clergyman. Blocksidge speculates that Henry was more than sufficiently well-funded to provide his son with an adequate living, and refused to do so largely out of spite. Still, it is somewhat surprising to read Hallam deprecating an income of “seven or eight hundred a year”: in Middlemarch, set around the same time period, Dorothea and Celia Brooke each receive £700 per annum from their parents’ estate, and Lydgate buys an entire medical practice assessed at £800.

At the time that the letters in the collection were first cataloged, this letter had not yet been published; but in 1981 Jack Kolb published it in his book The Letters of Arthur Henry Hallam.