Spring Byzantine Studies Symposium

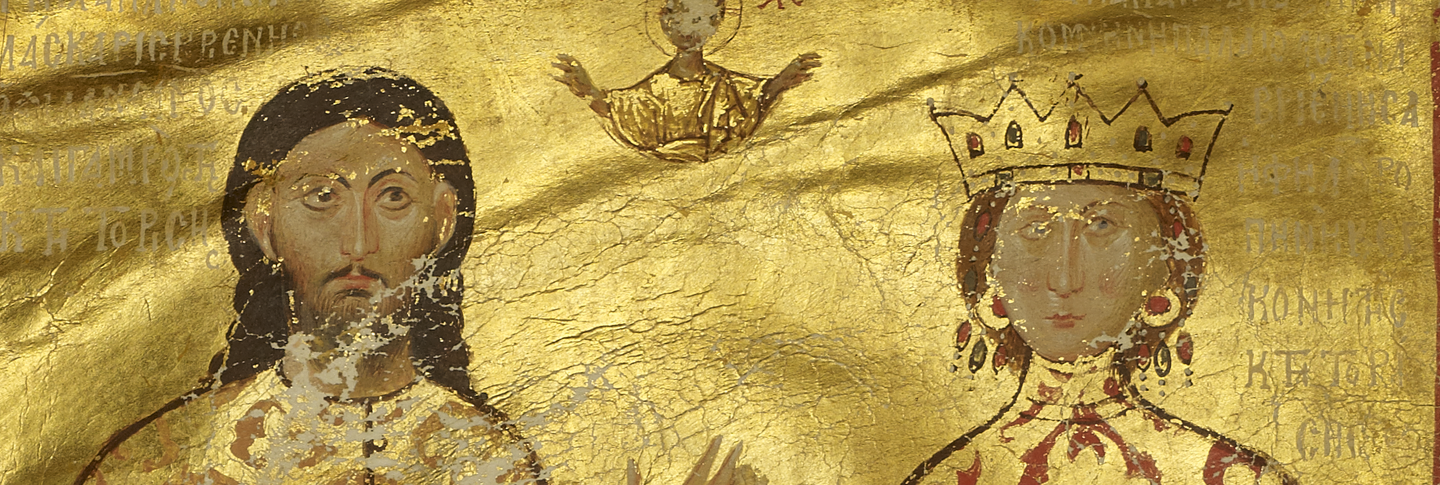

The Byzantine Portrait: Personhood and Representation

This event will occur in-person and will not be live-streamed or recorded.

In recent years, questions of identity, individuality, and subject formation have been at the forefront of Byzantine studies. Scholarship on autobiographical writings, for instance, has demonstrated that the adoption of exemplary voices and roles can enable self-expression, and therefore that the individual and the normative are not necessarily opposite. Similarly, students of Byzantine theology have drawn attention to the discourse on personhood that developed in the course of the trinitarian and iconoclastic controversies, and allowed Byzantine thinkers to conceive of the human subject both in its autonomy and in its relation to others. The cumulative effect of these studies is to undermine the strict dichotomy between individual and type. Subject formation in Byzantium is no longer negatively defined by the absence of Renaissance individualism. It is understood instead as a process of self-definition through engagement with multiple, sometimes widely varying, models.

These advances urge a reconsideration of the category of portraiture in Byzantine culture. How did individual and type play out in the visual realm? What was the human face ontologically and epistemologically, and how did it disclose identity? How did various conceptual frameworks and contexts of use—theological, legal, or ritual—enable portraits to stand in for, rather than merely represent, their human referents? And how did other media of representation, including inscriptions, monograms, and seals, relate to physiognomic likenesses? In pursuing these questions, we hope to formulate a new model of the Byzantine portrait. Such a model will necessarily be dynamic, changing over time as artistic media and conceptions of the self change. By bringing together art historians and scholars of Byzantine literature and theology, we seek to foster dialogue across disciplinary boundaries. Furthermore, we hope to place Byzantine images and texts in relation to recent historical and theoretical work on portraiture, personhood, and representation in the wider premodern world.

Symposiarchs

- Benjamin Anderson (Cornell University)

- Ivan Drpić (University of Pennsylvania)

Speakers

- Benjamin Anderson (Cornell University), “The Empire’s Three Persons”

- Ivan Drpić (University of Pennsylvania), “How to Portray a Serbian King”

- Michael Grünbart (University of Münster), “Condensing Personhood: The Monogram as a Non-Mimetic Form of Individual Representation”

- Cecily Hilsdale (McGill University), “Imperial Donors: Portraiture and Gift-Giving”

- Martin Hinterberger (University of Cyprus), “Physical Appearance and Literary Production as Aspects of Personal Identity in Byzantine Hagiography”

- Karin Krause (University of Chicago), “Author Portraits in Byzantine Manuscripts”

- Aden Kumler (University of Basel), Concluding Remarks

- Stavros Lazaris (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique), “Principles of Differentiation and Identity in Greek Scientific Manuscripts”

- Stratis Papaioannou (National Hellenic Research Foundation), “The Literature of the Self in Byzantium”

- Foteini Spingou (University of Edinburgh), “Between Stone and Soul: Shaping Byzantine Personhood through Tomb Epigrams”

- Thelma Thomas (New York University), “Book-men: Symbolic Portraits of Ascetics’ Lives in Late Antique Egypt”

- Alexis Torrance (University of Notre Dame), “The Ever-Depictable Individual, the Ever-Relative Image: Navigating Permanence and Transience in Byzantine Iconophile Thought”

- Alicia Walker (Bryn Mawr College), “Distributed Personhood and the Byzantine Lead Seal”

A limited number of Bliss Symposium Awards will be available to currently enrolled undergraduate and graduate students to attend Dumbarton Oaks symposia. The deadline for applying is March 15, 2024.

Image: Portraits of Michael Philanthropenos and Anna Philanthropene (detail), ca. 1330s. © Lincoln College, Oxford 2024, MS gr. 35, fol. 4r.

Past Topics

2020s

Ancient Histories and History Writing in New Rome: Traditions, Innovations, and Uses

May 5-6, 2023 | Byzantine Studies symposium exploring issues of identity, community, and memory in the eastern Roman Empire by examining the ways medieval historians engaged with and used classical Roman and Greek traditions of historical writing. Leonora Neville and Jeffrey Beneker, Symposiarchs.

History writing is a key site for the construction of ethical and political consciousness as well as historical memory. It allows individuals and communities to create and articulate their identity and positionality within the sweep of human history. In ancient Greece and the classical and medieval phases of the Roman empire, histories not only recorded past events, but either implicitly or explicitly told audiences how the past defined current communities and set moral and political agendas for future action. Different conceptualizations of the past amount to debates about who the authors thought they were, what was moral, and who their contemporaries ought to be. The study of traditions of historical writing is therefore an archaeology of civic identity, ethics, and politics.

This interdisciplinary symposium brought together scholars of ancient and medieval historical writing to explore connections and interactions between ancient Greek, biblical, classical Roman, and medieval Roman histories. Authors writing histories in eastern Roman society interacted variously with earlier Roman and Greek histories, as well as biblical histories, to construct conceptions of their community’s identities and relationships with the past. Rhetorical alignments signaled conformity with or breaking from pervious strands with these complex cultural traditions. Our explorations of the various ways medieval writers used, adapted, distorted, or ignored earlier texts helped us understand the complexities and nuances of medieval eastern Roman culture, community identity, and politics. In turn, the study of medieval uses of the classical historiographical tradition yielded fresh insights into the ways medieval attitudes and decisions shaped the preservation and creation of the classical canon.

Byzantine Missions: Meaning, Nature, and Extent

April 29–30, 2022 | Byzantine Studies Symposium

Though closely connected with the study of conversion and Christianization in the premodern era, the history of Christian missions has received little attention in recent scholarship. The recipients of Christian faith—individuals, nations, or social groups—and the processes of integrating the new religion have continued to attract analysis, but the agents of religious transformation have been relatively understudied, especially beyond the boundaries of medieval western Europe.

How did Byzantium missionize “barbarians”? To what extent did the motives, goals, or methods of missionaries themselves correspond with the vision of Byzantine rulers who may have sponsored them? This symposium examines the meaning of religious mission in Byzantium and how this concept shifted over time under changing political circumstances. Speakers consider literary works, linguistic evidence, and archaeological traces from Lithuania in the north to Nubia in the south, from Croatia in the west to the Golden Horde in the east. They examine how imperial policy built on or coincided with the unofficial missionary activity of monks, merchants, exiles, refugees, and captives. Concurrent with imperial efforts, Miaphysite and East Syrian churches, deemed heretical by the Orthodox Byzantines, conducted their own missionary endeavors reaching as far as Central Asia and China. What do the mission strategies of sibling Christianities suggest about underlying theological ideals, and what light might these comparisons shed on the nature of Byzantine missions?

The symposium aims to illuminate the inner motives that characterized Byzantine missions, the changing incentives that inspired them, and the nature of their missionary activity; and ultimately to better understand how the Byzantines perceived the universal claims of their empire and their church. At the same time, the organizers hope to throw light on the broader religious dynamics of the medieval world.

On Being Conquered in Byzantium

April 16–17, 2021 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Adam J. Goldwyn, Symposiarch

The famous adage that history is written by the victors may have become a truism, but the voices of conquered people have never been fully silenced—rather, we may not have been interested in hearing them. All too often, historiography (by no means limited to Byzantine studies) has focused on great-man histories, impersonal studies of societies, or the “longue durée,” all modes that diminish the importance of subjective individual experiences of people who were not great or who were not men.

This symposium therefore aims to refocus the collective scholarly gaze of Byzantinists away from the victors in war and toward the vanquished; away from heroes and rulers and toward victims and casualties; away from the political, economic, historical, and social causes of war and toward the personal and subjective experience of it; away from the insistence of dominant voices and toward the recuperation of marginalized ones.

Bringing together twelve specialists in literature, history, art history, and contemporary cultural theory, this symposium seeks to better understand both how Byzantines themselves understood being conquered and, as importantly, what being conquered in Byzantium can mean for us now.

Byzantine Missions: Meaning, Nature, and Extent

CANCELLED | April 24–25, 2020 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Sergey Ivanov and Andrea Sterk, Symposiarchs

2010s

Processions: Urban Ritual in Byzantium and Neighboring Lands

April 12–13, 2019 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Leslie Brubaker and Nancy Ševčenko, Symposiarchs

Military, civic, and religious processions were hallmarks of the ancient and medieval world; they continued into the Renaissance and, indeed, continue to this day. The Byzantine procession has not yet been subjected to any synthetic, historicizing, contextualizing, or comparative examination.

Understanding processions is critical for our appreciation of how urban space worked and was manipulated in the Middle Ages. For the 2019 Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Symposium, speakers will examine texts, artifacts, and images to develop a new understanding of medieval urban life across multiple social registers. For example, records of processions show us what kinds of public behavior were acceptable, and when, and where. Studying processions introduces us to new protagonists as well, for processions involve audiences as well as participants, and groups hitherto virtually invisible, such as the team of people who prepared for the event by decorating the streets, will be brought to light. The Byzantine commitment to processions is striking in terms of the resources and time allocated: there were as many as two processions a week in Constantinople, many involving the patriarch and the emperor. In the Latin West, the Crusader States, and in the Fatimid, Ottoman, and Muscovite worlds, by comparison, processions occurred far less frequently: the procession was significantly more important to the Byzantines than to their neighbors and successors. The comparative study of Byzantine processions to be offered by the speakers at the symposium will reveal how the Byzantines operated in a complex global network defined by local contexts, how the Byzantines positioned themselves within this network, and the nature of the Byzantine legacy to the Islamic, Catholic, and Orthodox inheritors of their culture.

The Diagram Paradigm: Byzantium, the Islamic World, and the Latin West

April 20–21, 2018 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Jeffrey F. Hamburger, David Roxburgh, and Linda Safran, Symposiarchs

Long discredited as inadequate illustrations of thought processes more appropriately represented in algebraic or verbal terms, diagrams have enjoyed a renaissance across numerous disciplines—from philosophy and computer science to the burgeoning field of graphics—as a means of visualizing knowledge.

As the historical disciplines take a fresh look at diagrams, this symposium will seek to offer an interdisciplinary, comparative, and cross-cultural perspective, considering the range of diagrams in Byzantium, Europe, and the Islamicate world. Its cross-cultural approach aims to decenter the bodies of scholarly work that focus on only one of these three traditions, within which it remains all too easy to take particular uses of diagrams for granted.

Among the questions our symposium will pose are: Why are diagrams relatively sparse (and certainly understudied) in the Byzantine and Islamic worlds? Why are they rarely adopted as vehicles of religious thought? What role do diagrams play in the development and documentation of scientific thought across the three traditions? How does the diagrammatic mode relate to artistic practice? To cartography? To science? To literature? To the school curriculum? Why is so much of “Western” medieval art diagrammatic in character, but so little of Byzantine and Islamic art? How do attitudes toward diagrams change over time? And how do the three traditions interact with one another?

Rethinking Empire

April 21–22, 2017 | Byzantine Studies Symposium

What do we mean when we call Byzantium an empire? A flurry of studies in recent years by historians of other hegemonic civilizations have situated empire and imperialism as historical phenomena across different periods and geographical areas. Until now, the involvement of Byzantinists in this reevaluation has been relatively marginal.

This symposium frames the issue of Byzantium’s imperial identity by setting it within wider contexts in the light of new research by Byzantinists as well as the approaches and methods profitably used by historians of other premodern and modern empires. The speakers will tackle fundamental problems of definition and will question Byzantium’s culture and institutions of empire, relations between core and periphery, territoriality, and ethnic diversity.

The centenary of the First World War, which has stimulated research on the competitive dynamics of the imperial powers that went to war in 1914, makes this symposium particularly timely. There is something highly symbolic in its venue, Dumbarton Oaks, whose founders, Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss, were close eyewitnesses to the bitter end of the modern “Age of Empire” during Robert Bliss’s diplomatic service in the U.S. Embassy in Paris (1912–19). Thirty years after the outbreak of the First World War, as the Second World War drew to a close, the Blisses and Dumbarton Oaks hosted the conference of world powers that led to the foundation of the United Nations.

Worlds of Byzantium

April 22–23, 2016 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Elizabeth S. Bolman, Scott F. Johnson, and Jack Tannous, Symposiarchs

The 2016 Dumbarton Oaks Spring Symposium, “Worlds of Byzantium,” seeks to reconsider Byzantium from Late Antiquity through the Middle Ages, problematizing long-established notions of its character and parameters.

In 1980 Dumbarton Oaks hosted the now famous “East of Byzantium” symposium, which resulted in an era-defining volume of scholarly articles under the same name, edited by N. Garsoïan, T. Mathews, and R. Thomson. This gathering of experts in various eastern Christian traditions put Dumbarton Oaks at the forefront of the emergent conversation about Byzantium’s eastern neighbors. Today, the medieval Mediterranean within which Byzantium was situated appears much more complex and fluid than what was envisioned thirty years ago. New archaeological, historical, and literary research has made this fluidity abundantly clear and has opened up new questions about the formation of identity in the empire as the relationship between the metropolis and the provinces fluctuated.

What was Byzantium? Where was it? What religions did its people practice, and which languages did they speak? The 2016 Symposium will examine the very foundations of what we think “Byzantium” was—Greek-speaking, Orthodox Christian, Constantinopolitan—and attempt to reset scholars’ expectations about what counts as Byzantine. Nevertheless, just as “East of Byzantium” transformed the expectations of a generation with regard to the value of eastern Christianity for medieval studies, we believe that Byzantium itself, however it is defined, can play a more central role on the world historical stage if Byzantinists are willing to let it be decentered and reconstituted for the next generation. This symposium will argue that a polycentric and interconnected Byzantium only strengthens Byzantine Studies as a discipline by making it indispensable to other fields: in order fully to understand essential aspects of the medieval Middle East or the medieval West one must also understand Byzantium.

The Holy Apostles

April 24–26, 2015 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Margaret Mullett and Robert Ousterhout, Symposiarchs

In the early years of Dumbarton Oaks, one of the research projects initiated by A. M. Friend was devoted to the church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. This early humanities collaboration of a literary scholar (Glanville Downey), an architectural historian (Paul Underwood), and an art historian (Friend) represented an attempt to reconstruct a lost building. A three-volume publication on the subject was envisaged, and a symposium was held in 1948, in which major scholars were involved, with Sirarpie Der Nersessian as symposiarch. Friend gave two lectures on the reconstruction of the lost mosaic cycle and Underwood spoke about the architecture. Der Nersessian herself gave two lectures on mosaics, while Downey spoke about literary texts, Milton Anastos about imperial theology, and Francis Dvornik about the patriarch Photios. As Kurt Weitzmann summarized, “It was a very unified program, demonstrating how Friend had been able to get every scholar at Dumbarton Oaks involved in his project.”

Unlike the Dumbarton Oaks projects on Norman Sicily or on Venice, the results of the Holy Apostles initiative were never published, nor was the 1948 symposium. Some materials survive in ICFA from the project, also unpublished. Nevertheless, the church of the Holy Apostles continues to attract scholarly attention from philologists, historians, and art historians. In the seventy-fifth year of Byzantine Studies at Dumbarton Oaks, a symposium devoted to the church of the Holy Apostles will complete the task of those early years by assessing the significance of the church, its milieu, and its legacy.

Knowing Bodies, Passionate Souls: Sense Perceptions in Byzantium

April 25–27, 2014 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Susan Ashbrook Harvey and Margaret Mullett, Symposiarchs

Byzantine culture was notably attuned to a cosmos of multiple dominions: material, bodily, intellectual, physical, spiritual, human, divine. Despite a prevailing discourse to the contrary, the Byzantine world found its bridges between domains most often in sensory modes of awareness. These different domains were concretely perceptible and were encountered daily amidst the mundane no less than the exalted. Icons, incense, music, sacred architecture, ritual activity; saints, imperial families, persons at prayer; hymnography, ascetical or mystical literature: in all of its cultural expressions, the Byzantines excelled in highlighting the intersections between human and divine realms through sensory engagement (whether positive or negative).

Byzantinists have been slow to look at the operations of the senses in Byzantium, especially those of seeing, its relation to the other senses, and phenomenological approaches in general. More recently, work on smell and hearing has followed that on seeing, and yet the areas of taste and touch—the most universal and most necessary of the senses—are still largely uncharted. Nor has much been done to explore how Byzantines viewed the senses, or how they envisaged the sensory interactions with their world. A map of the connections between sense-perceptions and other processes (of perception, memory, visualization) in the Byzantine brain has still to be sketched out. How did the Byzantines describe, narrate, or represent the senses at work? It is hoped to further studies of how individual senses in Byzantium operated in the context of all the senses, and their place in Byzantine thought about perception and cognition. Recent work on dreaming, on memory, and on the emotions has made advances possible, and collaborative experiments between Byzantinists and neurological scientists open further approaches.

The happy coincidence of this symposium with the upcoming Garden and Landscape Studies Symposium, “Sound and Scent in the Garden,” and a forthcoming exhibition at the Walters Art Museum on the five senses enables cross-cultural comparisons that include gardens in Islamic Spain, Hebrew hymnography, Syriac wine-poetry, Mediterranean ordure, and Romanesque and Gothic precious objects that were not just looked at but also touched, smelled, and heard. Architects, musicologists, art historians, archaeologists, philologists can all contribute approaches to the revelation of the Byzantine sensorium.

New Testament in Byzantium

April 26–28, 2013 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Robert S. Nelson and Derek Krueger, Symposiarchs

The New Testament lay at the center of Byzantine Christian thought and practice. Scribes copied its gospels and epistles. Lectionaries apportioned much of its contents over the course of the liturgical calendar; its narratives structured the experience of liturgical time and shaped the nature of Christian preaching. Quoted, alluded to, and expounded, it inspired and fueled the genres of hagiography and hymnography. Patrons and illustrators brought scenes from the life of Christ and his apostles to manuscripts, icons, and the walls of churches. Preachers, theologians and political theorists drew inspiration and authority from its teachings. Considering such varied legacies, this symposium assesses the impact of the New Testament on Byzantine civilization.

Following the successful symposium and volume on the Old Testament in Byzantium, we extend the investigation of the Bible in Byzantine history. We raise the following questions: What was the New Testament for Byzantine Christians? What of it was known, how, when, where, and by whom? How was this knowledge mediated through text, image, and rite? What was the place of these sacred texts in Byzantine arts, letters, and thought? We draw upon the current state of textual scholarship and explore aspects of New Testament manuscripts. But manuscripts of complete biblical texts, collections of texts, or entire Bibles were not the only or even the most important way in which the New Testament was understood, and accordingly, we explore the transformation of the New Testament as read, heard, imaged, and imagined in lectionaries, hymns, homilies, saints’ lives, and illustrations in miniatures and monuments. We turn also to the role of the New Testament in framing theological inquiry, ecclesiastical controversy, and political thought. Central is our conviction that liturgy, liturgical arts, and intellectual culture offered places where exegesis continued, long after the tradition of Patristic biblical commentary had ceased. Our interdisciplinary conversation yielded fuller knowledge of the New Testament and its varied reception over the long history of Byzantium.

Rome Re-Imagined: Byzantine and Early Islamic Africa, ca. 500–800

April 27–29, 2012 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Susan T. Stevens and Jonathan P. Conant, Symposiarchs

The short period of Byzantine rule in the Maghreb belies the region’s importance to the empire in the sixth and seventh centuries. Given the profound economic and strategic significance of the province of “Africa,” the territory was also highly contested in the Byzantine period—by the empire itself, Berber kingdoms, and eventually also Muslim Arabs—as each of these groups sought to gain, retain control of, and exploit the region to its own advantage. In light of this charged history, scholars have typically taken the failure of the Byzantine endeavor in Africa as a foregone conclusion. The symposium sought to reassess this pessimistic vision both by examining those elements of Romano-African identity that provided continuity in a period of remarkable transition, and by seeking to understand the transformations in African society in the context of developments in the larger post-Roman Mediterranean. An international group of researchers from North America, Europe, and North Africa, including both well-established and emerging scholars, addressed topics including the legacy of Vandal rule in Africa, historiography and literature, art and architectural history, the archaeology of cities and their rural hinterlands, the economy, the family, theology, the cult of saints, Berbers, and the Islamic conquest, in an effort to consider the ways in which the imperial legacy was re-interpreted, re-imagined, and put to new uses in Byzantine and early Islamic Africa.

Saints and Sacred Matter: The Cult of Relics in Byzantium and Beyond

April 29–May 1, 2011 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Cynthia Hahn and Holger Klein, Symposiarchs

The physical remains of holy men and women and objects associated with them embody aspects of the divine and therefore play a central role in a number of religions and cultures. Given their ability to link the past and present with an imagined future, sacred remains, or relics, were especially important to the development of Christianity as they testified to Christ's presence and ministry on earth and established a powerful connection between God and man after his resurrection. The Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles bore early witness to the healing powers of Christ and his disciples and drew attention to the places, where these miracles occurred. Moreover, cities such as Jerusalem, Constantinople, and Rome, where objects associated with Christ's Passion were kept and where bodies of saints and martyrs were buried, soon developed into important cult centers, drawing pilgrims in large numbers from across the Late Roman Empire. Enshrined in sumptuous metal, ivory, or stone containers, relics formed an important physical and spiritual bond between heaven and earth, linking humankind to their saintly advocates in heaven. As they were carried in liturgical processions, used in imperial ceremonies, and called upon in legal disputes and crises, relics—and, by extension, their precious containers and built shrines—provided a visible link between the living and the venerated dead.

Coinciding with Treasures of Heaven. Saints, Relics and Devotion in Medieval Europe, a major exhibition on relics and reliquaries from Late Antiquity to the end of the Middle Ages at The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, this year's symposium addressed a variety of issues surrounding the cult of saints and relics in Byzantium, the Medieval West, and the Islamic East. It sought to pose a series of questions that were intended to open new windows onto the cult of saints and relics in Byzantium and beyond. How did Early Christian cult practices emerge from ancient Greek, Roman, and Jewish traditions? How did reliquaries develop as containers of sacred matter, and what kinds of models inspired their earliest makers? What mechanisms governed the exchange and translation of holy relics and assured their efficacy in new social, religious, and cultural contexts? How did these objects and the shrines in which they were preserved and displayed transform the memory of extraordinary individuals into saintly bodies who connected heaven and earth? What role did art and architecture play in the construction of holiness and the animation of sacred matter? In what ways do physical objects link the past with the present and connect cities and their communities across time and space? What impact did relics have on the development of three-dimensional religious sculpture in the West, and what role did two-dimensional representations of holy figures play in the re-presentation of saintly bodies in the East?

The symposium was held at two venues, namely at Dumbarton Oaks (Friday and Sunday) and The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, giving attendees an opportunity to visit and explore the exhibition.

Dante and the Greeks

October 1–3, 2010 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Jan Ziolkowski, Organizer

This three-day symposium included attention to Dante’s views on ancient Greece and its cultures as well as on medieval Greece and its cultures. Scrutiny was given to the presence of ancient Greek poetry and philosophy (such as Homer, Plato, Aristotle) as well as science (astrology, cosmography, geography) in Dante’s works. In addition, participants explored the Greek characters (drawn indirectly from the ancient Greek mythographic tradition, Homeric epic, and other such sources) that populate Dante’s works, as well as others (such as the Cretan Veglio).

Speakers considered the degree to which such influences were filtered to the Italian poet through Patristic and late-antique texts (by Origen, the Cappadocians, Dionysius the Areopagite, and others), since Dante could have been introduced to at least some of the original ancient literature by way of these intermediaries. The symposium also investigated very broadly the medieval assimilation of Greek thought into Christian culture. This assimilation included Byzantine influences on political thought, particularly on the centrality of the emperor and the empire as ideas and ideals (Justinian and the juridical and political thought of the Eastern Roman Empire). This issue relates particularly, but not exclusively, to Dante's De monarchia.

Beyond a strict concern with Dante lies the challenge of setting him in a broader context with regard to the perception and reception of Greek in the thirteenth-century West. Latin Christians manifested a schizophrenic outlook, instead of a single Greekness there were several, not all of them even interconnected. First of all were the pagan Greeks and then the Byzantine Greeks. Even the Byzantines were far from uniform, since Westerners responded very differently to the traditions of the Greek Church fathers and of their own contemporary Greeks. Thus Greek was not only a past language or culture, but also a present (and often rival) religious and political entity. To each of these layers Latins related somewhat differently. Doctrinal, political, linguistic, cultural, educational matters all played important roles in shaping attitudes, and in this regard travel and diplomacy are perhaps as relevant as translations.

Warfare in the Byzantine World

April 30–May 2, 2010 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, John Haldon, Symposiarch

War and the need to wage it, the organisational constraints it imposes, its effects on society and economy as well as its ideological justification and the debates it engenders, can be a radical force for social and political transformation. However unpleasant the effects of war, it is an undeniable fact of human history that war has been on many occasions and in many different historical contexts a powerful stimulus both to technological innovation and social and political change. The crucial role of war and its concomitants cannot be ignored in the history of any culture. Byzantium is no exception. Indeed, in many respects the history of the Byzantine state is also the history of its ability successfully to defend itself and to organise for war, for its military organisation was central both to the inflection of its social relations in general as well as to the ways in which the central government extracted and redistributed the resources available to it, whether in the form of agricultural produce or money taxes on agriculture and trade.

In its thousand years of existence—from the reign of Anastasius (491–518) until that of the last emperor, Constantine Ⅺ (1448–1453)—the Byzantine state was almost constantly at war with one or another of its neighbours. This reflected its geography and strategic situation, centred as it was on the southern Balkans and Asia Minor. It had constantly to fend off challenges to its territorial integrity from the Persian and then Arab or Turkish Islamic powers to the east, or its Balkan or central European neighbours to the north west and north. As the western and central European powers grew and matured—first in the form of the Carolingian empire, then the German empire and the kingdom of Hungary—so Byzantine political pre-eminence came to be challenged, until by the end of the twelfth century the empire had become a second-rate state, subject to the power politics of powerful western kingdoms and the commercial strength of Italian merchant republics such as Venice, Genoa and Pisa.

Byzantium was a society in which the virtues of peace were extolled and war was usually condemned, certainly when taken for its own sake. Fighting was to be avoided at all costs. Yet the empire nevertheless inherited the military administrative structures and, in many ways, the militaristic ideology of the expanding pre-Christian Roman empire in its heyday. These tensions were overcome through the blending of Christian ideals with the political will to survive and the justification of war as a necessary evil, waged primarily in defence of the Roman world and the Orthodox faith. Late Roman and medieval Christian society in the eastern Mediterranean/south Balkan region thus generated a unique culture which was able to cling without reservation to a pacifistic ideal while at the same time legitimating and justifying the maintenance of an immensely efficient and, for the most part remarkably effective, military apparatus.

This symposium examined some of these themes in an attempt to re-evaluate Byzantine as well as other perceptions of warfare and the military, to understand how the Byzantines organised for war, and the reasons for their success or failure.

2000s

Morea: The Land and Its People in the Aftermath of the Fourth Crusade

May 1–3, 2009 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Sharon Gerstel, Symposiarch

I'm going to tell you a great tale, and if you will listen to me, I hope it will please you. The opening line of the Chronicle of the Morea sets the stage for this symposium, which examines the late medieval Peloponnese following its conquest by the Crusader knights in 1205. Far from ancestral homelands in France, the Crusaders found a land that "was fertile, spacious and delightful with its fields and waters and multitude of pastures." The Chronicle, written sources, and the buildings and artifacts that are left to us or recovered archaeologically reveal a bold attempt to establish a new kingdom in this distant land, adding yet another layer to the many levels of habitation on the island of Pelops. Omitted from this myth of Crusader foundation are the large numbers of Orthodox villagers and town dwellers who also shared the region and created their own myths of an eternal and sacred empire generated by the pains of loss and the hopes of refoundation. Their remains, though less studied, are also left in the written and material records of the period. Layered upon the historical and physical topography of this region, as well are the traces of the Venetians, whose right eye, Modon, was sited at the southwestern tip of the peninsula. The Turkish layers, revealed in standing fortresses, toponyms, vernacular poetry, and pottery, also left deep traces on the ground and remain in collective memory. How these groups and others who shared the land interacted and how they established corporate identity is at the center of this symposium. At the core of our investigation, too, is the understanding of place and memory – the recollection of the ancient history of the Peloponnese, the architectural and cartographic marking of its mountains and valleys, and the re-creation of distant capitals on its land. The speakers in this symposium look at the Morea and its people in the broadest possible manner and with careful attention to written and material evidence, historiography, and the making – or re-telling – of myths.

Trade and Markets in Byzantium

May 2–4, 2008 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Cécile Morrisson, Symposiarch

Over the last decades archaeological evidence has played a great part in reshaping our perspectives and understanding of trade in Byzantium from Late Antiquity to the late Byzantine period. The symposium first looked back into the historiography of the debate on the role of the state in Late Antique exchanges and then gave the state of the art of research on the movement of goods at various levels within the Byzantine world, with particular importance given to regional exchanges. In relation with the temporary exhibition of coin weights, scales and their context in the reopened Byzantine gallery, the symposium focused equally on markets and the market place, which have up to now been studied essentially from the Constantinopolitan point of view. It was hoped that bringing together historians, archaeologists and epigraphists will help us combine the "macro" perspective with a "micro" and less familiar one.

Old Testament in Byzantium

December 1–3, 2006 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Paul Magdalino and Robert Nelson, Symposiarchs

This symposium, designed to complement an exhibition of early Bible manuscripts at the Sackler Gallery of Art, examines the use of the Greek Old Testament as text, social practice and cultural experience in the Byzantine Empire. Not only are reminiscences of the Old Testament ubiquitous in Byzantine literature and art, but Byzantines revered and identified with Old Testament role models. The phenomenon has never received systematic investigation, despite the fact that this was the part of its tradition that Byzantium shared most widely with other cultures - not only its Christian neighbors, but Judaism and Islam.

Becoming Byzantine: Children and Childhood in Byzantium

April 28–30, 2006 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Arietta Papaconstantinou and Alice-Mary Talbot, Symposiarchs

Byzantinists have shown little interest for children and childhood, even after the fin-de-siècle surge of studies on that topic in classical, medieval and early modern studies. Two recently published books and two doctoral dissertations devoted respectively to orphans, childhood disease, children's education, and the visual representation of children, do show an increasing curiosity about the topic. Even so, the bibliography on Byzantine childhood remains a short one, and does not include any substantial general overview. One of the aims of the conference will be to provide this overview, by looking into as yet neglected aspects of childhood in Byzantium.

The focus of the conference was on the Middle and Late Byzantine periods, the ones most neglected hitherto, although some of the papers included materials from Late Antiquity as well. The papers concentrated on the basic subjects of definition, legal and social status, representation, life and death, education and acculturation, but issues of everyday life, such as toys and games, were addressed as well.

Urban and Rural Settlement in Anatolia and the Levant, 500-1000 AD: New Evidence from Archaeology

April 22–24, 2005 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Clive Foss and Johannes Koder, Symposiarchs

This topic was designed to provide a comprehensive survey of current knowledge of these crucial areas in the Eastern Mediterranean during a period of profound transformation: in Asia Minor, from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages; in the Levant from Byzantium to Islam. Hopefully, the subject illuminated history from a variety of viewpoints, crossing traditional boundaries between history and archaeology and between Byzantine and Islamic studies.

Sessions were devoted to all kinds of human settlement during this period, ranging from the large metropolitan cities of the late Roman Empire to villages of the early Middle Ages, as well as fortresses and monasteries. Archaeology received particular attention, since it is the main source for potential understanding of these topics. The talks, therefore, were largely be based on the results of recent excavations and surveys, though without neglecting the evidence derived from the narrative or documentary historical record.

Questions of methodology were stressed, both in an introductory session and in the individual papers, so that the audience could understand what kind of information may now be derived from a range of techniques, and how it may be integrated with the more traditional sources. It was hoped that the sum of the individual topics both reflected the advances that have been made in recent years, and helped towards an understanding of major historical questions in the Fall of Rome, the rise of Islam and the survival of Byzantium.

On the Thursday preceding the opening of the symposium, at 5:30 P.M., Prof. Cyril Mango of Exeter College, Oxford University, delivered a keynote lecture open to all. His topic was, Byzantine Asia Minor and Syria: From Art Historical Monuments to Archaeological Settlement.

Egypt and the Byzantine World, 450–700

April 30–May 2, 2004 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Roger Bagnall, Symposiarch

The relatively early loss of Egypt to the Byzantine empire has contributed to its marginal role in Byzantine studies. For the early Byzantine period, however, Egypt is an exceptionally rich field, with a range of evidence unparalleled elsewhere in the empire, thanks largely to its preservation of organic materials. The speakers in this Symposium contributed to a synthesis that reflects the major discoveries and broad intellectual trends of the study of early Byzantine Egypt in recent years. The Symposium resisted the commonplace division of the society and culture of Egypt in this period into "Greek" and "Egyptian" (or "Coptic"), an old dichotomy increasingly rejected by recent scholarship. Rather, each speaker reflected on how the complex cultural amalgam of early Byzantine Egypt appears as a case study in the light of the empire as a whole. In this way both Egypt's participation in the metropolitan culture of the period and its more distinctive traits can be brought out.

Among the questions speakers considered were the nature and development of the Roman cities of Egypt in the fifth to seventh centuries, their relationship to the surrounding villages, and their functions as centers of government and the economy. The urban role in the production of artóin a period where monasticism dominates the surviving recordówill also was assessed. A second set of contributions looked at Egypt's place in the empire, both in its participation in common institutions like the army, public administration, law, and the hierarchy of the church, and in its distinctive but by no means isolated religious life and identity. On the cultural side, speakers looked at Egypt's role as both producer and consumer of literature and art and considered how far the place of gender roles in Egypt was characteristic of Byzantine society more broadly. The final session focused on monasticism, an area in which Egypt made particularly distinctive and renowned contributions to the larger world.

The Sacred Screen: Origins, Development, and Diffusion

May 9–11, 2003 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Sharon Gerstel and George Majeska, Symposiarchs

Speakers in this symposium confront one of the defining elements of religious architecture and ritual: the construction of screens to define boundaries and thresholds within sacred spaces. Woven from cloth or chiseled from stone, painted with figures or carved with decorative emblems, and built to various heights or lengths, screens have framed sacred thresholds throughout history. As the material expression of a critical liminality, the screen intensifies ritual, marks passages, and orders communities. Its function as a barrier is often secondary to its facilitation of ritual performance and access to the divine. Paradoxically, the ubiquity of barriers in sacred spaces has often been the cause of their invisibility in historical, theological and liturgical sources. The near absence of contemporary notice and the problematic and contested nature of the surviving evidence makes the study of sacred screens particularly challenging to modern scholars.

For several decades, scholars have been seriously engaged in studying the origins and development of the chancel barrier in the medieval West as in Byzantium, and with very interesting results. Lacking in this research, however, have been two elements: first, a conceptual element that would raise questions about why such barriers should appear and what they might signify, and, second, a comparative element that would take note of regional variations in chancel barriers and try to explain the causes of these differences. In addressing these points, speakers at the symposium look at the following questions: What is the nature of the segregation between clergy and laity in cult buildings? How does this separation of sanctuary from nave relate to other separating mechanisms in sacred edifices, such as those segregating according to gender, or according to standing in the community? How is the relationship between sanctuary and nave different from the relationship between sacred space and secular space, temple and world? In what ways is the specific nature of the separating devices reflective of the theological perspectives of the worshippers? Is the altar screen necessarily different in conception or function from the inner wall of the Greco-Roman altar or the veil of the Jewish temple? Is the Western rood screen qualitatively different from the Byzantine templon? Why do the Russians develop a high iconostasis when non-Chalcedonian Eastern churches can make do with a curtain?

Invoking a broad range of materials, cultures, and perspectives, the 2003 Dumbarton Oaks Symposium shed light on the nature of the sacred screen, its early manifestations through the most recent ritual scholarship.

Realities in the Arts of the Medieval Mediterranean, 800–1500

April 26–28, 2002 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Anthony Cutler and Angeliki Laiou, Symposiarchs

Art History has come a long way in the thirty years since Otto Demus' Byzantine Art and the West. We think now in terms of communications rather than influences, regions rather than centers and peripheries, demand rather than supply, consumption and reception rather than the role of magisterial models. These innovations are more than matters of wording: they reflect shifts in the conceptual foundations of our discipline, prompted as much by critical theory as by the discovery of new evidence.

But in the wake (and light) of the theoretical "revolution", it is perhaps time to reconsider fundamental questions about the means by which motifs, techniques and ideas traveled from one region to another. What, for example, is the relation between mosaic workshops attested in the Holy Land and those of Constantinople? Can we make sense of the tangled relations between Arab and Byzantine silk and ceramic production? How, and from where, did Western historiated initials arrive to grace Greek books? When and how did Byzantine methods of ivory carving reach Egypt? By what means were Ayyubid metal-working practices disseminated? Can we assess the impact of Venetian industrial arts upon the Central and Eastern Mediterranean? What were the mechanisms that allowed the apparent confluence of Latin and Greek themes in "Crusader" wall painting and manuscripts? Is it useful to distinguish between economic and non-economic exchange, or separate this from more broadly based clientèles?

Some answers can be derived, as recent research has shown, from scrutiny of the objects themselves. But given the limited survival of many, these need to be viewed against the background of the written sources. While documents such as the Geniza archives have been exploited, others - notably the terms of trade treaties, Italian commercial documents and Arab gift lists - would seem to throw light upon the filiations between objects of allegedly very different origin that art historians recognize on stylistic and technical grounds. All in all, we are calling for the integration of the artifactual and historical evidence, the former providing clues to what may be significant in the documents, the latter furnishing a context for and quite possibly a pattern to the distribution of goods in the Mediterranean between the ninth and fifteenth centuries.

Late Byzantine Thessalonike

May 4–6, 2001 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Jean-Michel Spieser, Symposiarch

After the conquest of the Byzantine Middle East by the Arabs in the 7th century, Thessalonike remained the only major town in the Byzantine empire, except of course Constantinople; despite the Slavic attacks, it continued to serve as a real urban center, the most important in Greece. The significance of Thessalonike increased paradoxically in the last Byzantine centuries, after the re-establishment of the Byzantine empire by Michael VIII Palaiologos in Constantinople. Even in the middle of the civil wars, which were so frequent in the 14th century, Thessalonike on occasion became almost a rival of the capital. Despite its troubled situation, Thessalonike experienced a flourishing religious, intellectual and artistic life: in no other period since early Christian times were so many churches built and decorated.Despite (or because of) this complex historical situation, whose political, economic, artistic and intellectual aspects deserve to be addressed as well, since the beginning of the 20th century no real synthesis has been attempted about late Byzantine Thessalonike. The increasingly rich documentation and numerous valuable studies on specific topics now provide the basis for a new approach. Through this symposium we tried to give some fresh insights and to begin to fill this gap.

Pilgrimage in the Byzantine Empire, 7th–15th c.

May 5–7, 2000 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Alice-Mary Talbot, Symposiarch

Interest in the subject of pilgrimage in the eastern Mediterranean world has intensified in recent years, as manifested in new courses on early Christian, Byzantine and Islamic pilgrimage, exhibitions, and special conferences on the subject. With regard to eastern Christian pilgrimage the emphasis has been on travel to the Holy Land, especially during the period of the 4th–6th centuries for which the evidence is more abundant. The symposium planned at Dumbarton Oaks for May 2000 is intended to stimulate research in new directions by focussing on a later period and examining the phenomenon of pilgrimage in the Byzantine world from the 7th–15th c.

After the conquest of the Holy Land by the Arabs in the 7th c. new patterns of pilgrimage developed. Although Byzantines in limited numbers continued to journey to the loca sancta of Palestine, there was a marked shift in patterns of pilgrimage in the middle and late centuries of the Byzantine empire. Cities such as Constantinople, which acquired major relics of Christ's Passion and of the Virgin, and Thessalonike with its shrine of the martyr saint Demetrios, became major pilgrimage sites. Cults also developed at the tombs of new local saints, leading to the appearance of healing shrines in both urban and rural areas of Greece and Anatolia. Other foci of pilgrimage were holy springs (haghiasmata), holy icons and living holy men.

1990s

Byzantine Eschatology: Views on Death and the Last Things (8th to 15th Centuries)

April 30–May 2, 1999 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, George Dennis and Ioli Kalavrezou, Symposiarchs

Constantinople: The Fabric of the City

May 1–3, 1998 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Henry Maguire and Robert Ousterhout, Symposiarchs

The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World

May 2–4, 1997 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Angeliki Laiou and Roy Mottahedeh, Symposiarchs

Aesthetics and Presentation in Byzantine Literature, Art, and Music

May 3–5, 1996 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, John Duffy, Symposiarch

Palestine and Transjordan before Islam

April 28–30, 1995 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Jean-Pierre Sodini, Symposiarch

Byzantine Court Culture from 829 to 1204

April 22–24, 1994 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Henry Maguire, Symposiarch

Byzantium and the Italians, 13th–15th Centuries

April 30–May 2, 1993 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, John Barker and Angeliki E. Laiou, Symposiarchs

Law and Society in Byzantium, 9th–12th Centuries

May 1–3, 1992 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Dieter Simon, Symposiarch

Byzantine Civilization in the Light of Contemporary Scholarship

May 3–5, 1991 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Speros Vryonis, Jr., Symposiarch

The Holy Image

April 27–29, 1990 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Hans Belting and Herbert Kessler, Symposiarchs

1980s

The Byzantine Family and Household

May 5–7, 1989 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Angeliki Laiou, Symposiarch

Byzantium and the Caucasus: Confrontation and Interaction between the Empire, Armenia, and Iberia

April 29–May 1, 1988 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Nina G. Garsoïan and Robert W. Thomson, Symposiarchs

Mount Athos

May 1–3, 1987 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Nicolas Oikonomides, Symposiarch

Ecclesiastical Silver Plate in Sixth-Century Byzantium

May 16–18, 1986 | Byzantine Studies Symposium

Byzantium and the Barbarians in Late Antiquity

May 3–5, 1985 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Evangelos Chrysos, Symposiarch

Byzantine Art and Literature around the Year 800

April 27–29, 1984 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, David H. Wright, Symposiarch

Byzantine Medicine

April 29–May 1, 1983 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, John Scarborough, Symposiarch

Continuity and Change in Late Byzantine and Early Ottoman Society

May 14–16, 1982 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Anthony Bryer and Heath Lowry, Symposiarchs

Art in Norman Sicily

May 1–3, 1981 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Ernst Kitzinger, Symposiarch

Syria and Armenia in the Formative Period

May 9–11, 1980 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Nina G. Garsoïan, Thomas F. Matthews, and Robert W. Thomson, Symposiarchs

1970s

Byzantine Liturgy

May 10–12, 1979 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, John Meyendorff, Symposiarch

Venetian Mosaics and Their Byzantine Sources

May 11–13, 1978 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Otto Demus, Symposiarch

The Transmission and Reception of Knowledge

May 5–7, 1977 | Byzantine Studies Colloquium, John Murdoch, Colloquiarch

Urban Societies in the Mediterranean World

April 30–May 2, 1976 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, David Herlihy, Symposiarch

Monte Cassino

May 1–3, 1975 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Herbert Bloch, Symposiarch

The Decline of Byzantine Civilization in Asia Minor, Eleventh-Fifteenth Century

May 2–4, 1974 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Speros Vryonis, Jr., Symposiarch

Art, Letters, and Society in Byzantine Provinces

May 3–5, 1973 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Ihor Ševčenko, Symposiarch

Current Work in Medieval and Byzantine Studies

May 4–5, 1972 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Ernst Kitzinger, William Loerke, Cyril Mango, and Ihor Ševčenko, Symposiarchs

Byzantine Books and Bookmen

April 29–May 1, 1971 | Byzantine Studies Colloquium, Cyril Mango and Ihor Ševčenko, Colloquiarchs

Byzantium and Sasanian Iran

April 30–May 2, 1970 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Ihor Ševčenko, Symposiarch

1960s

Byzantine Society

May 1–3, 1969 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Peter Charanis, Symposiarch

After the Fall of Constantinople

May 2–4, 1968 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Kenneth M. Setton, Symposiarch

Justinian and Eastern Christendom

May 4–6, 1967 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, John Meyendorff, Symposiarch

The Age of Constantine: Tradition and Innovation

May 5–7, 1966 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Alfred R. Bellinger and Richard Krautheimer, Symposiarchs

The Byzantine Contribution to Western Art of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

April 29–May 1, 1965 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Ernst Kitzinger and Kurt Weitzmann, Symposiarchs

The Byzantine Mission to the Slavs: St. Cyril and St. Methodius

May 7–9, 1964 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Francis Dvornik and Roman Jakobson, Symposiarchs

The Relations between Byzantium and the Arabs

May 2–4, 1963 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Hamilton A. R. Gibb, Symposiarch

The Hellenistic Origins of Byzantine Civilization

May 3–5, 1962 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Romilly J. H. Jenkins, Symposiarch

The History of Byzantine Science

May 4–6, 1961 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Milton V. Anastos, Symposiarch

The Mosaics and Frescoes of the Kariye Djami, Their Cultural and Artistic Background

May 5–7, 1960 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Paul A. Underwood, Symposiarch

1950s

Antioch-on-the-Orontes in the Byzantine Period

April 30–May 2, 1959 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Glanville Downey, Symposiarch

Studies in Byzantine Art

May 1–3, 1958 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Sirarpie Der Nersessian, Symposiarch

Byzantium in the Seventh Century

May 2–4, 1957 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Ernst Kitzinger, Symposiarch

The Cappadocian Fathers

May 3–4, 1956 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Werner Wilhelm Jaeger, Symposiarch

Palestine in the Byzantine Period

April 21–23, 1955 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Carl H. Kraeling, Symposiarch

Byzantine Liturgy and Music

April 29–30, 1954 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, A. M. Friend, Jr., Symposiarch

The Cultural Era of Constantine Porphyrogenitus

April 30–May 2, 1953 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Kurt Weitzmann, Symposiarch

Byzantium and the Slavs

April 24–26, 1952 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Reverend Francis Dvornik, Symposiarch

Iconoclasm

April 26–28, 1951 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, A. M. Friend, Jr., Symposiarch

The Emperor and the Palace

April 27–29, 1950 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, André Grabar, Symposiarch

1940s

The Relations between Byzantium and Its Neighbors

April 28–30, 1949 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Robert P. Blake, Symposiarch

The Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople

April 22–24, 1948 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, S. Der Nersessian, Symposiarch

Byzantine Art and Scholarship

April 25–26, 1947 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Concluding Sessions of the Bicentennial Conferences of Princeton University

Hagia Sophia

May 2–4, 1946 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, A. A. Vasiliev, Symposiarch

The Decorations in the Synagogues of Dura-Europos

April 26–28, 1945 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Albert Mathias Friend, Jr., Symposiarch

Portraits and Biographies in Byzantine Manuscripts

April 27–29, 1944 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, Albert Mathias Friend, Jr., Symposiarch

Byzantine and Mediaeval Art and Literature

April 29–May 1, 1943 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, George La Piana, Symposiarch

Byzantine Seminary

October 9–11, 1941 | Byzantine Studies Symposium, E. K. Rand, Symposiarch