The South Lawn

In Farrand’s first known letter to Mildred Bliss written in June 1922, she describes the importance of the South Lawn as a front facing element that would frame a visitor’s experience of the rest of the estate. “The whole feeling of the entrance front of the house should be one to be gained through easy flowing lines, dark masses of foliage, considered quite as much from the point of view of winter effect as summer space and quietness.”

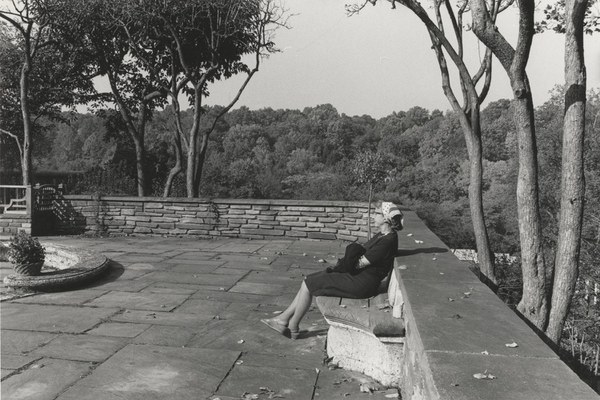

The North Vista

Providing a lofty vantage point at the top of the gardens, the North Vista solidifies the stately presence of the house itself and then looks out to the woodland landscape, a quintessential American view. Farrand designed the garden room drawing on the human experience of perspective, with walls that narrow and terrace downward (ever so slightly) in three parts giving the illusion of a much longer expanse of land shooting out into the distant greenery.

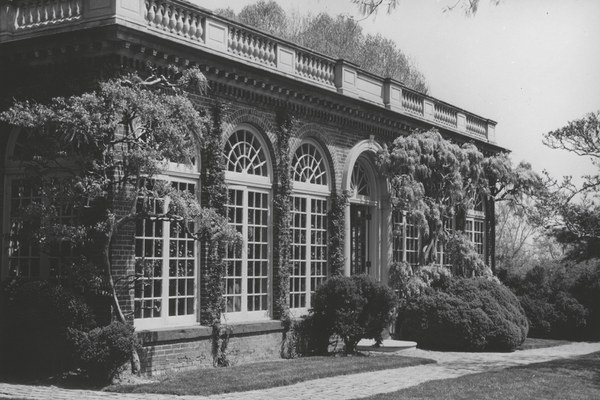

The Orangery

The Orangery serves as a portal into the Dumbarton Oaks Gardens. The oldest building on the grounds of the estate, the room welcomes visitors into the world of Farrand’s designs lying just beyond its doors. Its significant placement was not lost on Beatrix Farrand, who in her “Plant Book for Dumbarton Oaks” described the view from the Orangery looking south to be “one of the real horticultural events of the Dumbarton season.”

The Green Garden

Stepping through the doors of the Orangery, one is delighted by the sight of a majestic southern red oak tree. Fittingly placed as a testament to the namesake for Dumbarton Oaks, the tree canopies the Green Garden: the highest overlook on the property. The directional pull of the room is toward an outlook where a sloping view of the garden terraces as they descend the slope, as well as the Adams Morgan neighborhood beyond. The dichotomy between urban neighborhood and designed wilderness provides a sense of the “country house in the city” aesthetic so desired by the Blisses.

The Rose Garden

With the sloping topographical landscape of the Dumbarton Oaks estate and the terracing of the gardens, one is hard-pressed to find a center to the gardens’ design. If there is any garden room that could serve as such, it is the Rose Garden. Beatrix Farrand designed the Rose Garden, the flattest and largest formally designed garden room, to be a commanding presence. The room was of particular significance to Robert and Mildred Bliss, and it is where their ashes were interred—behind the Finalities Plaque.

The Fountain Terrace

Beatrix Farrand’s first inclination with Terrace D was toward an English Arts and Crafts Garden. After Farrand designed the room in 1925, Mildred Bliss’s tastes began to shift in response to her affection for Edith Wharton’s reflecting pool outside of Paris. Farrand therefore redesigned Terrace D into a French-inspired fountain terrace with two symmetrical, elliptical pools in 1927. These pools, originally unadorned, were embellished by identical putti fountains purchased from a French dealer in 1931.

The Arbor Terrace

The Garden Archives preserves a large number of planting plans, and the Arbor Terrace’s complex, shifting history can be told through the narrative of planting choices. The flora in this room are planted in beds and pots with an especially high level of intentionality. The degree of care exhibited by Beatrix Farrand in placing flowers is liken to a seasoned art collector arranging masterpieces in a room. Each piece is perfectly placed.

Lovers’ Lane Pool

In the dappled sunlight of the southeast corner of the estate lies Lovers’ Lane Pool. Bordering Lovers’ Lane, a local walking and access route from Georgetown into Rock Creek Park, this garden room is an oasis of reflection tucked away behind baroque columns and a green shroud of bamboo. The pool was once a lily pond before Beatrix Farrand began to sculpt the land in 1925.

Herbaceous Border

The Herbaceous Border is one of the most elegantly colorful rooms at Dumbarton Oaks. Planted in the style of an English border as described by Gertrude Jekyll in Garden Ornament, the beds are framed by a green yew hedge, providing a simple background against which the cool palette of lavenders, pinks, and light blues plays out. In recent years, the garden staff has focused on increasing the number of perennials while reducing the number of annuals so as to make the room a “three-season” garden, with different blooms throughout the year.

Kitchen Gardens

The space the Kitchen Garden currently occupies was one of the larger areas Beatrix Farrand encountered when she arrived in 1921. Her first priority was connecting the two separate terraces by a staircase, which she designed in 1925. The upper terrace would become a flower garden used for cuttings, while the lower would provide space both for a vegetable garden and a field to prepare other garden plantings as well as house chrysanthemums. It is likely that in the pre-Bliss period, the owners of the estate would have grown produce on the property, tended to and harvested by enslaved laborers.

Ellipse

Mildred Bliss first dreamed of the Ellipse as a child, and Beatrix Farrand realized the vision through her design in the mid-1920s, with construction completed in 1933. Farrand’s Ellipse was constructed entirely of boxwood and included the grassy slope of Box Walk in a singular unit she called the “Box Garden.” This Ellipse was dense yet soft and oriented inward toward a fountain with a single jet sitting on an island surrounded by a moat. The boxwood hedge in the Ellipse made it one of the most private spaces in the Blisses’ garden.

Woodlands

Beatrix Farrand initially imagined that Dumbarton Oaks Park would be a continuation of the Blisses’ gardens following a European tradition of estate landscapes including wilderness areas on the outer edge. The Park originally provided a wooded buffer around the property, giving the Blisses the feel of the “country house in the city” they so desired. In 1940, following the donation of the Dumbarton Oaks collections and gardens to Harvard, the Blisses bequeathed 27 acres of designed park land to the National Park Service.