Bat-ami Artzi received her PhD from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and is a fellow in Pre-Columbian Studies. Her research report, “The Vilcabamba Piece as a Watershed between Ancient and Colonial Andean Art,” described the unique iconography and cultural context of a ceramic vessel known as the Vilcabamba Piece.

Q&A with Bat-ami Artzi

What was Vilcabamba, and what is the vessel known as the Vilcabamba Piece?

Vilcabamba was the last refuge of the Incas during the Spanish invasion in the sixteenth century. A fragment of Inca nobility moved to the area in hopes of regaining control and reconquering the empire’s territories from the Spaniards. One of the settlements, Espiritu Pampa, was excavated between 2008 and 2014 by the Ministry of Culture of Peru. In the complex called Tandi Pampa, which served as a temple with spaces for food and drink preparation, archaeologists found maize and dehydrated potato. Though it is a humid region, the foods were well-preserved because the site was set on fire by the Inca when they fled in 1572, so a layer of ash covered most of the buildings in the site.

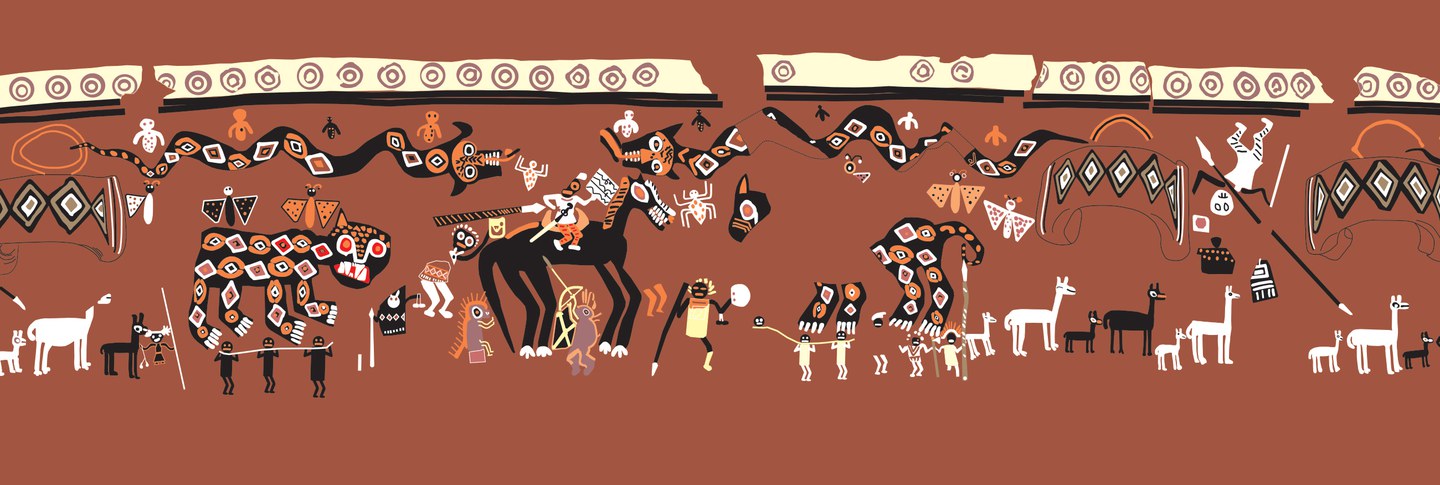

They also found 55 ceramic fragments that were all part of one piece known as the Vilcabamba Piece. Though not all the fragments have been found, reconstruction suggests it was a large, four-handled vessel. It’s remarkable for many reasons; most information on the final days of the Inca Empire comes from Spanish chroniclers, and this Inca-made vessel is a pictorial testimony from the heart of the Inca resistance. The scene painted on the piece is quite unique too. Inca art is generally geometric, but the Vilcabamba Piece displays an unusual degree of figural complexity with approximately 39 human figures, 57 animals, and other objects like weapons.

What is significant about the iconography?

The scene displays the importance of duality to the Incas through the organization and use of colors. There are two main foci of the iconography, each showing a Spaniard, who can be identified through their clothing and weapons. On one side of the vessel, the Spaniard is depicted riding a black horse; on the opposite side of the vessel, the Spaniard is shown riding a white horse. On the other two sides are two dead Spaniards, one of whom is depicted with an Incan spear passing between his head and body. This creates four sections corresponding with the four handles. The quadripartition and repetition of the number four are also essential to the message of this piece, echoing how members from the four parts of the Inca Empire combined forces against the invaders.

The iconography also seems to depict both present and future. The two Spanish riders are shown underneath a rainbow shape, which symbolizes critical change or pachacuti. However, the rainbow has black lines, indicating an evil pachacuti, so these two Spaniards are associated with evil change—the present for the artists making the vessel. Outside the rainbow area, each of the Andeans fighting the four Spaniards are dressed distinctly from one another, and a few of them wear attire representative of the four different parts of the empire. This part of the scene seems to show a future when the Andeans defeat the Spaniards through cooperation among the empire’s four parts.

What does this tell us about the artistic and cultural context of the piece?

The Vilcabamba Piece is an amazing example from a transition period, combining elements from ancient and neo-Inca art. For example, the art has many similarities with Moche art, though the Moche were active many centuries earlier. Art from the Chimu—which emerged after the Moche but in the same region—was strongly inspired by the Moche. The Chimu were eventually conquered by the Incas, so their art may be the connection with the iconography we see on the Vilcabamba Piece.

The vessel’s message of a promising future also resembles that of Taki Unquy, a messianic movement resistant to the Spanish invaders. The movement believed huacas—divinities and sacred places of the Andean societies—would one day unite to defeat the Spanish Catholic God. The huacas would fight in two groups, one led by the divinity Pachacamac, whose temple was located on the central coast of Peru, and the other by Titicaca, whose temple was located on an island in Lake Titicaca. Like the four regions of the Inca empire uniting to resist the Spaniards, the huacas would unite against the Spanish God. Four felines that appear on the vessel, divided into two pairs, may also be related to this messianic vision. In each pair, one of the felines possibly represents Pachacamac and the other Titicaca; this composition continues a long tradition of feline pairs in Andean art, as we see in a Wari tunic in the museum. Felines and rainbows are also persistent motifs in colonial art, showing that Inca art was modified but still lived on after the fall of the empire.

May Wang is postgraduate writing and reporting fellow. Drawing by Arturo Rivera Infante.