By Nicole Eddy

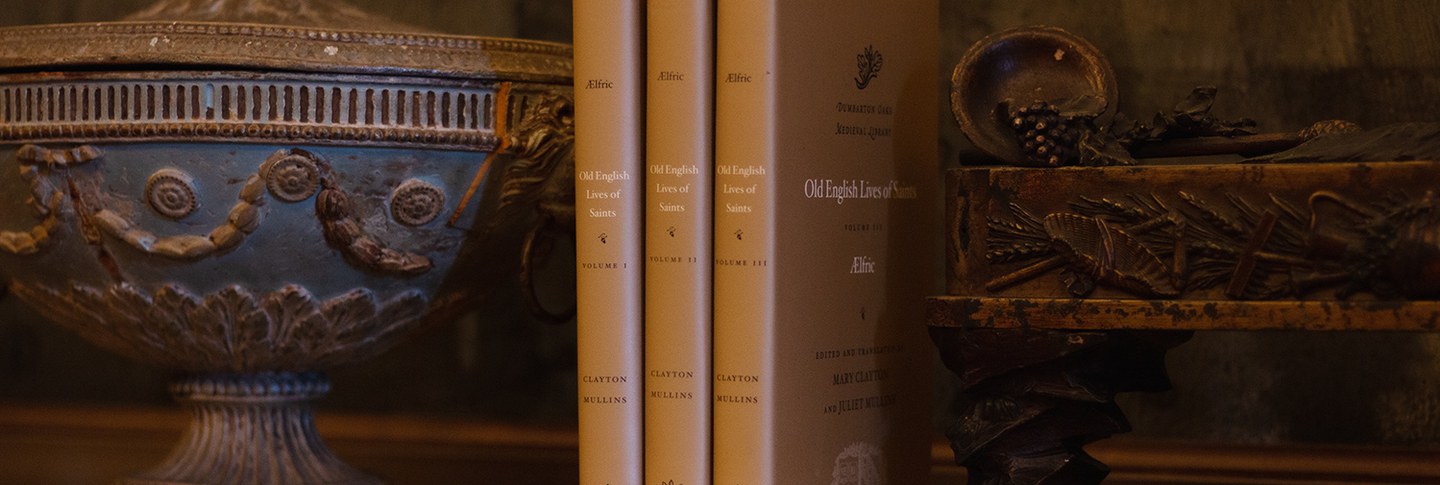

Ælfric, the tenth-century monk and author, wrote in the Old English preface to his Lives of Saints, “we say nothing new in this work, because it was written down long ago in Latin books, although lay people did not know that.” Created for the benefit of two powerful aristocratic patrons related to the English royal family, his project provided versions of the stories of saints’ lives, along with some sermons, that could be read, listened to, and meditated on even by those who were not priests, monks, or nuns. Those people who didn’t know the Latin language of the educated elite were being left out, with no way to learn from and enjoy reading the exemplary lives of Christianity’s heroes. In three volumes just published in the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library series, Mary Clayton and Juliet Mullins (both of University College Dublin) have gone back to the surviving manuscripts to present a brand-new edition and translation of Ælfric’s Lives of Saints and once again bring these stories to a whole new audience.

Ælfric wrote the Lives in the last decade of the tenth century, while living at the Benedictine monastery of Cerne Abbas in Dorset. Probably the schoolmaster there, he was also one of the most important authors of tenth-century England and wrote works both in Latin and in Old English, the form of English in use before the increased French influence that occurred after the Norman Conquest of 1066. These included an Old English grammar of the Latin language and translations of the Old Testament, both revolutionary at a time when works like these would usually be read in Latin alone, not in the vernacular languages spoken by the majority of people.

Saints’ lives themselves were no restrictive genre in the Middle Ages, but allowed authors great freedom to experiment with everything from history to moral exemplar to fantastic tales of magic and miracles. Saints’ lives were a fertile way for medieval writers to tell exciting stories, full of heroes and villains, adventure and inspiration, but all within a framework that invited readers to take lessons for their own daily lives. Some of the saints featured in the collection are still popular ones today. Saint Martin, for example, later the bishop of Tours, was a soldier in his youth in the army of the Roman emperors Constantine II (r. 337–361) and Julian the Apostate (r. 361–363). On one frigid winter day, while he was traveling with some companions through the city of Amiens, he came upon a freezing beggar. Not having any money or possessions besides the clothes on his back, Martin cut his cloak in half to share with the beggar, an act of generosity in which he donated not just what he himself did not need, but an equal share of what he did.

Or there is Saint Dionysius, a composite that conflates Dionysius the Areopagite (an Athenian convert and follower of Saint Paul) with an anonymous fifth-century author known only as Pseudo-Dionysius and with Saint Denis, the patron saint of Paris. In the resulting hybrid tale, Dionysius journeyed from Athens to Roman-controlled Gaul, where he was beheaded at the orders of a persecuting Roman prefect. The head rolled some distance away, but Dionysius’s body miraculously arose and picked it up: the body walked more than two miles, carrying the head and singing a hymn, accompanied by a choir of angels. His executioners were so impressed by the miracle that they converted to Christianity themselves. Although none of the extant manuscripts containing Ælfric’s Lives are illustrated, both Martin and Dionysius have been popular subjects for artistic depictions throughout the Middle Ages and beyond.

Some of the saints in the collection, like the seventh-century Æthelthryth, abbess of Ely, or the ninth-century bishop of Winchester Swithun, pictured below just a couple of decades before Ælfric was writing, were local favorites for Ælfric’s tenth-century English audience. Others hailed from far away and long ago, but still reinforced the Christian values of Ælfric’s own time by defying the hierarchies of power in their own. Saint Maurice, the leader of a “separate legion of eastern peoples, devoutly Christian men,” was drafted into the army of the Roman emperor Maximian (r. 284–305). When Maurice defied the orders of the pagan emperor and refused to participate in “idolatrous rites,” Maximian ordered him executed. In Ælfric’s account, he is an outsider who rises to prominence and personal success within a flawed system, but who then does not shrink from defying that system when it threatens his beliefs. By the thirteenth century it was common to show this leader of the Egyptian “Theban legion” as a black man, often carrying a Roman imperial standard.

Another Egyptian saint profiled by Ælfric is Saint Eugenia, the daughter of the Roman prefect of Egypt. She converted to Christianity after reading the writings of the apostle Paul. With the help of her two eunuch servants, also converts, she cut her hair short, disguised herself as a man, and became a monk, eventually rising to the rank of abbot. Her deception was only discovered many years later, when a lustful widow falsely accused the disguised Eugenia of an attempted seduction. Eugenia refuted the accusation by dramatically revealing her true identity to the prosecuting official—her own father, who, overjoyed to discover his lost daughter again, himself converted to Christianity together with their entire family. Eugenia’s adopted masculinity is in the end no refuge, but a trap she must escape; meanwhile, the lustful widow provides a misogynist stereotype balancing the positive exemplar presented in chaste Eugenia. Yet Eugenia’s dedication to her faith, her “masculine spirit,” and the lengths she goes to in order to embrace an ascetic life in God’s service, offer inspiration not just to other women, but to her father, brothers, and servants.

Ælfric’s Lives tells stories about everyone from soldiers to bishops, and ranges from Paris to Roman Egypt. In doing so, it brings the wide world of early medieval Christianity out of Latin and into English, a stage in the ongoing process of interpretation and readaptation that has resulted in renewed, reimagined, and repainted versions of these stories from antiquity to the present. In this fresh translation, they find a new audience once again.

Buy Ælfric’s Lives of Saints and browse other DOML volumes at domedieval.org.

About the Images

To learn more about the images featured in this post, visit the National Gallery of Art’s page on Saint Martin and the Beggar and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s page on Saint Maurice. Those two pictures show how later artists imagined some of these early saints, but the illustration of Saint Swithun was made much nearer to Swithun’s own day, and no more than a few decades before Ælfric was writing: read more about the book where Saint Swithun appears at the British Library. For interesting comparisons to the Saint Martin image, take a look at one eleventh-century illustration depicting Martin about to blow a devil off the shoulder of a cruel Roman prefect with a puff of air. Or come to Dumbarton Oaks in person, where another painting by the Renaissance artist El Greco is on display.

Nicole Eddy is managing editor of the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library.