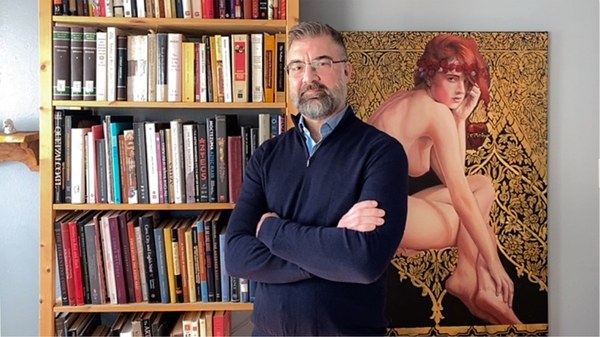

Patrick Hajovsky, associate professor of art history and affiliate faculty for Latin American and border studies at Southwestern University, is a 2020–2021 fellow in Pre-Columbian Studies. His research report, “Sculpting Across the Conquest: Indigenous Artistic Practice and Sacred Knowledge in Central Mexico,” considered how Aztec and colonial-period sculpture primed Indigenous embodied knowledge of the sacred, especially in terms of the body and its sacrifice.

Q&A with Patrick Hajovsky

What is teixiptla, and how does it relate to Aztec sculpture?

Teixiptla is a Nahuatl term, literally translated as “image” or “representation.” But in documents like Bernardino de Sahagún’s Florentine Codex, it’s used more like “god embodiment,” which still implies a Platonic separation between the person and the god but gets closer to how the person became a god through wearing the god’s accoutrements and learning how to behave like the god.

I’m exploring when teixiptla can be applied to sculptures to ask about the life of the sculpture. Some sculptures were meant to be present and visible permanently; others may have been buried at one point, ritually destroyed. One sculpture I study is the badly fragmented portrait of Moteuczoma at Chapultepec Park in Mexico City. He’s adorned with the accoutrements of “Our Lord the Flayed One,” Xipe Totec, the god of springtime, renewal, and warrior sacrifice. But is Moteuczoma dressed like the god, or just covering himself with accoutrements that he had as king—is his sculpture a teixiptla? The sculpture may have existed in a ritual framework like other living teixiptla—inscribed hieroglyphs refer to calendrical cycles, including rituals and deeds of the king’s past. But the sculpture was also meant to be present and seen in a particular landscape in the Basin of Mexico.

What is the role of image, place, and space in sculpture?

Aztec symbolism is bound with the cardinal directions, but we lack the full context of many objects that have survived, especially of their orientation, though some orientation can be inferred through inscriptions. For example, the Templo Mayor in the sacred precinct of Tenochtitlan was perfectly aligned for the sun to pass between the twin temples on the equinox, and caches in the temple held offerings oriented in the cardinal directions and in layers, starting from the ocean, up to the earth and sky.

There is also a throne-sized temple model called Teocalli, which, as Emily Umberger has shown, could have served as a ritual seat or throne, suggested by its excavation near Moteuczoma’s palace. The king or teixiptla could have sat on the temple platform with the temple as the backrest and his legs dangling over the staircase. The sitter would become like a cosmological model, because images of the earth and sun are inscribed on the surface of the seat and backrest. Through this symbolism, the sun would be carried on the back of the sitter, like the king carrying the sun. If the temple-throne were oriented according to inscriptions on the sides pertaining to directional gods, it would have mirrored the main temple, which faces in the opposite direction.

Why is it important to bring together sculpture and text?

There is a large body of manuscript studies that provides important information for the interpretation of the sculptures, but that implies manuscripts are primary texts to the sculptures, and I take issue with that. I think it’s important to recenter our “primary text” to the sculptures themselves, which are complicated, three-dimensional “texts” as well as forms meant to interact with a notion of the body and place, mirrored or projected from these created objects. Sculptures also existed independently of manuscripts and were interactive and performative with humans in different ways than manuscripts can describe.

The inspiration for this idea comes from poet Gloria Anzaldúa, whose writing reclaims the past with a method based not necessarily on knowing through textual understanding but rather through an embodiment that arises innately. She has this profound mirroring moment with the great sculpture of Coatlicue when she moves beyond her fear or distrust of this innate embodiment, allowing herself to be consumed by the great goddess, seeing from within it and emerging anew in the end. The experience suggests memory is not just what we’ve been told and learned but also something we deeply understand just by being.

I am thinking through a methodology that engages with the form and surface of sculpture by considering how the Aztecs may have thought about sculptures as relational bodies. Researching from home has gone smoothly so far with the help of Pre-Columbian Studies Librarian Flora Lindsay-Herrera, who works closely with Pre-Columbian content and has dealt expertly with various resource issues. I’m working from afar, through digital images, with several objects in the collection, notably the Xiuhcoatl or fire serpent that has Moteuczoma’s name hieroglyph underneath, and the mask of Tezcatlipoca; [Associate Curator, Pre-Columbian Collection] Juan Antonio Murro is really great at providing images so I can see many of the details that will help me without actually being there.

May Wang is postgraduate writing and reporting fellow at Dumbarton Oaks. Photo by Richard Tong, postgraduate digital media fellow.