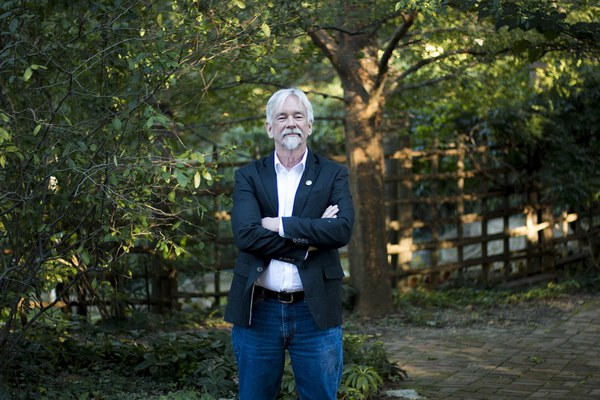

Terence Young, professor emeritus of geography at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, was acting director of landscape architecture studies from 1996 to 1997. His Mellon Midday Dialogue, “To Feel at Home in the Wild: E. P. Meinecke’s Modern Autocampground,” revealed how public parks in the 20th century created the illusion of wild nature for campers while protecting plants from human harm.

Q&A with Terence Young

How did Emilio P. Meinecke transform the American camping landscape?

About 50 million Americans camp every year, give or take. When camping began in the 19th century, you did it on foot, you did it on horseback, or you did it with a wagon and horses. Then the 20th century came along, with the automobile and new roads. People could now take cars and go camping in huge numbers.

Before Meinecke, in many public protected areas in the United States—state parks, national parks, forests—people were allowed to camp basically anywhere they wanted. At national parks like Yosemite, Yellowstone, Sequoia, and Glacier, the number of people who came was so large that their camping anywhere became destructive. The Park Service brought in Meinecke because the redwood trees—the sequoias in Sequoia National Park – were being damaged by the hordes of campers. It’s not good to damage the thing the park’s there to protect.

Emilio Pepe Meinecke, or “Doc,” was a plant pathologist who was born in California in 1869, got a PhD in botany from the University of Heidelberg, and returned to California when he was around 40. He told the Park Service, look, I have a plan you should adopt. You’ve got to designate campsites, which all campers must use. And then you have to lay out the campsites in such fashion that there will be minimal damage caused to the natural vegetation.

So we went from this kind of free-for-all to what most people would experience today if they went to a car campground. They wouldn’t be surprised to drive down a road to campsite number 17, which has a table and a fireplace, set up a tent, and go back to pay their fees.

When I told people I’d discovered this man and came to realize what he was doing, I said I felt like I had found the person who invented the vacation. It makes you think, really? Somebody invented this? And it’s this plant pathologist?

In your talk (part of the Mellon Initiative in Urban Landscape Studies), you mentioned that camping created the “illusion of wildness.” What role does urban life play in camping?

National parks and forests attracted people because they didn’t have the regulation, rules, clocks, and so on that irritated people in cities. But in spite of its attractions, most people’s understanding of the natural world was really limited. What Meinecke did was blend the urban life people knew with mythic nature. At his campsites, there’s a fixed place where you cook and burn things—a kitchen, if you will. There’s a table for people to sit at. There’s a place for their bedroom, that is, the tent. There’s even a place for the car, which Meinecke called a “garage spur.”

Other people had introduced urban features to camping. What’s really distinctive and surprising about Meinecke’s plan is that at the same time as bringing these urban features, he recognized that the point of being there was to get away from urban life. For example, instead of fence barriers, he recommended using logs and other natural materials to guide people’s movements. Americans are—it seems somewhat unfair to call them anti-urbanists, but at least urban uncomfortablists. Camping is enormously popular in this country, but it might not be if the country’s cities were more comfortable and less stressful.

Meinecke made it possible for so many more people to have a mediated, domesticated experience of nature. It’s an urban-based domestication. And the public was happy about it. You were very hard-pressed to find anybody complaining about campgrounds after this transformation happened.

Why should landscape historians pay attention to the experience of everyday Americans?

When you’re driving up to Yosemite, in California, you enter a very long, narrow tunnel called the Wawona Tunnel, come out on the other side, and bam, there’s Yosemite Valley: the falls, Half Dome, the large parking lot that usually has hundreds of cars in it, sometimes 1000 people, all taking pictures of the landscape Ansel Adams memorialized. Everybody’s seen that picture.

Landscape architects designed that tunnel. It introduced what in landscape architectural history is the element of surprise or the picturesque, verging on the sublime. Landscape architects didn’t do this because some rich Rockefeller told them to. The layout of the national parks in the United States was driven by the tastes of average Americans. The public has an idea about what they think the national parks are. And people like Thomas Vint—the landscape architect who got that tunnel built—said, okay, let’s give them the parks they think they have.

Julia Ostmann is Postgraduate Writing and Reporting Fellow at Dumbarton Oaks. Photo by Elizabeth Muñoz Huber, Postgraduate Digital Media Fellow.