Although the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection transferred to Harvard in November 1940, the first fellows and scholars did not take up residence until early February 1941. Director John Thacher wrote Mildred Bliss in California on February 5, 1941, about their arrival:

Lester Houck, the first student in residence, arrived last Friday, and is apparently very happy in the quarters. Several members of the American Council of Learned Societies who were here last Saturday for tea and to see the collection spoke very highly of him and said that he was exactly the type of person who should be here and that if all of our students were of the same quality, Dumbarton Oaks would be setting a very high standard in scholarship. Then yesterday, Miss Florence Day, who is chiefly interested in Persian and Islamic art arrived. I put her into the room formerly used by Miss Godden as a sitting room, as Miss Godden assured me that she did not need the room at all. As it has its own bath and is separate from the other rooms on the third floor, it was most convenient to be able to use it. I did not want to put her down in the garage all alone. Professor Morey is scheduled to arrive on Sunday with two of his pupils. Morey, of course, will be in the house, and the two students will be in the quarters with Houck. This will fill up one end of the quarters. I doubt whether there will be any more resident students this year. Focillon is particularly happy about this as he, as well as Koehler, feel that for this year at least it is wise not to have too many.

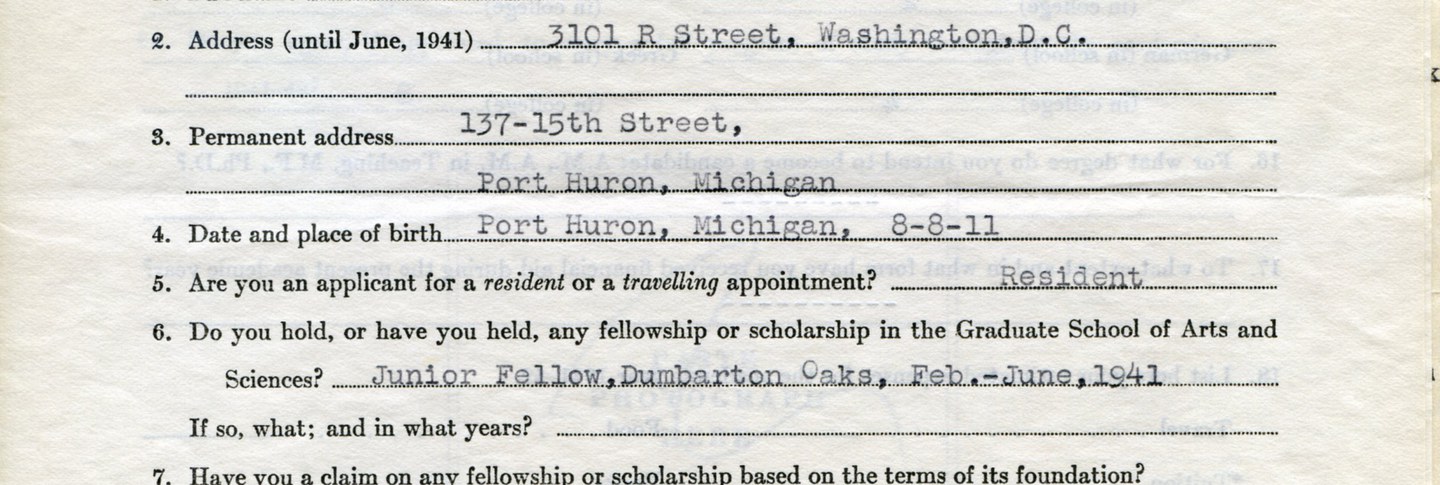

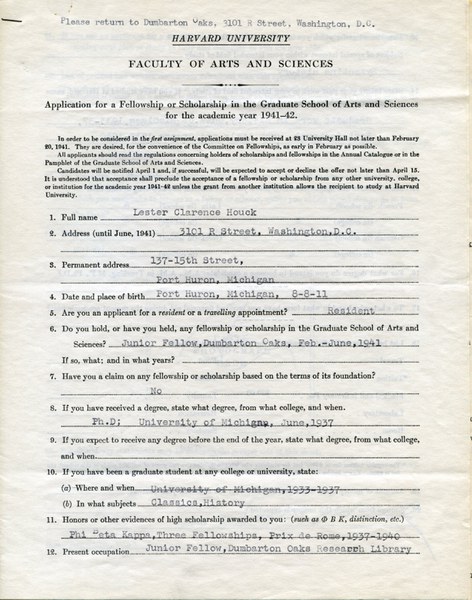

Lester Clarence Houck (1911–80), the first junior Fellow at Dumbarton Oaks, received a baccalaureate in 1934 and a doctorate in 1937 from the University of Michigan. His dissertation was titled “The History of Leo Diaconus, An Edition,” which he planned to prepare as a publication at Dumbarton Oaks, although he never brought the work to press. In 1939, he was a Fellow at the American Academy in Rome.

In the Underworld Courier 1, no. 17 (June 5, 1941), the occasional newsletter that the staff at Dumbarton Oaks sent to the Blisses in California, he is described as

six feet, six inches tall. He lowers his head when going through many a door; is lean—as so tall a person is apt to be—with a head which is distinguished in an intellectual way. The written word, the recorded thought, is his absorbing passion. Perhaps his selections from the research library are along certain definite lines, but from the general literature sections, he borrows, 4 or 5 at a time, books ranging from Dante and Gerard Hopkins to Harold Nicolson and Maurice Baring. His humor is plentiful, if pedagogic, and though his scholastic opinions appear to be quite firmly established, he has a pleasant receptivity to the potential usefulness of books with titles such as: Mazes and Labyrinths. . . Origins of Applied Chemistry. . .

On May 30, 1941, at the end of his fellowship, Houck wrote to Mildred Bliss:

When I left Italy in September I felt that I should not find any place in America where my researches could be appropriately carried on. I was astonished to find that you had conceived here a center for such studies. May I tell you how grateful I am for your having made possible this opportunity for me to carry on my studies in Byzantine history during these four months and my admiration for your generosity and vision?

He went on to recount the first “Commencement at Dumbarton Oaks, May 1941”:

I presume that you have been made aware how much the presence of Prof. Focillon and Prof. Morey, perfect Nestors, have contributed to the success of our mutual work. Last Tuesday after the final colloquium we had dinner together and then “exercises” in the music room in which degrees and diplomas, honoris causa, were bestowed in Latin. I have before me the citation or ‘epitaph’ I composed for Prof. Focillon and I have enclosed a copy with the thought that it might interest you.

Houck’s Latin “epitaph” for Henri Focillon reads as follows:

Henricus Focillon, vir eruditissimus et reverendissimus, indigator et pacificator atrium Orientalium et Occidentalium earumque imperator benignus, fons et origo librorum, socius regalis horum Quercorum Dumbartonensium, cum Focus atrium, ut nomen suum indicat, focus calens, ardens, benevolub, jocosus, plenus inspirationis sit, hic et nunc Doctor Eloquentiae Convivalis, hoonoris causa, Quercorum proclamatur et omnibus privilegiis ad hanc honorem pertinentibus induitur!

Salve, Doctor!

[Henri Focillon, a man most learned and most reverend, investigator and pacifier of the arts of the East and the West and their benign emperor, fountain and origin of books, royal Fellow of these Dumbarton Oaks, since he is a Fireplace (as his name indicates) of the arts, a fireplace warm, ardent, benevolent, jocose, full of inspiration, here and now is proclaimed Doctor of Convivial Eloquence of the Oaks, for the sake of the honor, and is endowed with all the privileges pertaining to the honor!

Hail, Doctor!]

Houck was a junior Fellow between February and June and September and December 1941. However, when the United States entered the Second World War after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he left Dumbarton Oaks and joined the War Department's Office of Strategic Services, an intelligence agency, where he was chairman of the Dissemination Branch in the office of the Assistant Secretary of War. He remained there until at least 1946 and did not return to Dumbarton Oaks.