Walking along a residential street in the middle of a city, you might briefly consider the shade-casting branches of overhanging trees, or the sough of leaves mingling with the whir of distant traffic. You probably wouldn’t reflect, however, on the embattled histories of individual trees, the aesthetic theories that (often literally) helped to shape them, or the intricacies of city-planning that either frustrated or ensured their existences.

Sonja Dümpelmann thinks about just these things.

On October 19, Dümpelmann, a landscape historian and associate professor of landscape architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, as well as a senior fellow at Dumbarton Oaks, delivered a lecture as part of the Mellon Midday Dialogue series which outlined her recent research into the history of street tree planting and its relation to urban development.

Though the book Dümpelmann hopes to write on the subject will focus on twentieth-century Berlin and New York, her talk, “Street Tree Stories: On the Politics of Nature in the City,” stepped further into the past in order to examine the curious and oftentimes dramatic stories that have sprung up around urban trees.

Historically, trees have been prone to personification. In ancient times dryads roamed the earth in the guise of beautiful women; when spotted, they swiftly transformed themselves into oaks. Even today, as Dümpelmann explained, a bit of paganism resurfaces in the wintertime as children pack snowballs onto trees, forming eyes, a nose, a winning grin.

In simple terms, this mythological baggage means that, in more recent times, trees have often functioned as epicenters of emotion. Place a tree in the middle of the city, as Dümpelmann illustrated with a series of anecdotes, and the emotions tend to run even higher.

Dümpelmann recounted the story, preserved in a newspaper snippet from 1897, of the Matthews family, who woke one morning to find that a telephone company had dug three postholes in the front yard of their home in Brooklyn. When the family members learned that the company planned to topple their large shade tree to make room for a skein of telephone wires, they promptly leapt into the postholes and refused to budge.

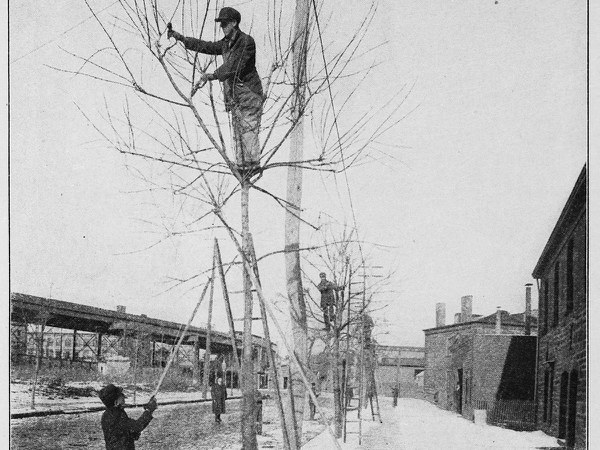

As cities continued to grow in complexity in the early twentieth century, conflicts concerning their trees turned theoretical and oftentimes scientific. The science of arboriculture spread, and the position of city forester became professionalized.

What is the ideal tree, its type, its shape? While cottonwoods, as some argued, were initially appealing, their cloudy seedpods had a tendency to stick to the clothing of those passing under them. At the 1867 World’s Fair in Paris, the newly invented dendroscope—basically a large wire cookie cutter for trees—promised uniformity in the pruning of trees, and came in a variety of ovoid iterations.

Displaying images from pruning manuals and handbooks, Dümpelmann explained that the process of standardization, made manifest in the Victorian-era innovation of the dendroscope, presaged the widespread practice of arboriculture. With time, aesthetic concerns gave way to concerns over the interactions of architecture and verdure, and even to questions of public health.

In the early years of the twentieth century, street trees had become such a prominent concern that rampant debate about their pros and cons could materialize even in the literary realm. To close her presentation, Dümpelmann read an exchange of poems between a leading arboriculturist and a writer for The New Yorker. Pithy, humorous, and mutually dismissive, like parodies of pastoral verse, the poems nevertheless encapsulated the fervent hopes and beliefs sprouting from the contentious trunks of the city’s trees.