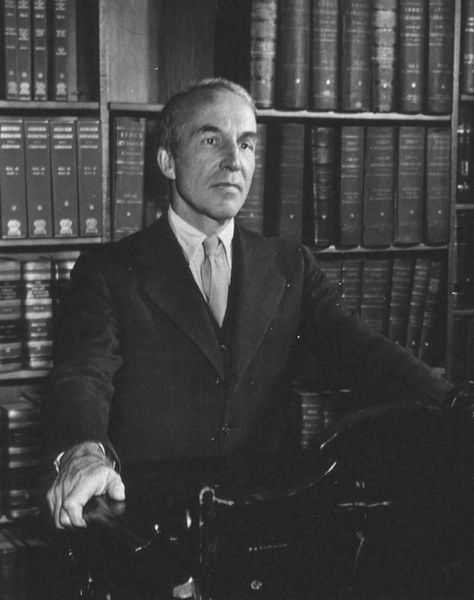

Archibald MacLeish (1892–1982), 1944.

In January 1941, Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss prepared to leave Washington, D.C., and Dumbarton Oaks, first for Florida and then for California, where they planned to spend the remainder of the winter at their house, Casa Dorinda, in Montecito. Before their departure, the socialite Marie Beale (1880–1956) hosted a going-away party for the Blisses and their Washington friends at her home, Decatur House. At the party, the poet and writer Archibald MacLeish (1892–1982), who was Librarian of Congress from 1939 to 1944, read the Blisses a letter recounting the guests’ memories of their visits to Dumbarton Oaks. Mildred Bliss spoke of this event in a letter of January 29, 1941, to her friend Rosamund Eustis: “Marie organized a most charming tribute to Dumbarton Oaks from our Washington friends—a little book with many signatures and a rarely grave and charming evocation of Dumbarton Oaks written by Archibald MacLeish. It was presented with cleverly contrived humor, so that there were no tears nor snifflings—for which we are doubly grateful to her.”

MacLeish’s text is as follows:

To Robert and Mildred Bliss:

This letter, signed with so many names, is nevertheless a very simple letter. It is a letter of thanks. It is a letter written by men and women who have found in the house you made an unforgettable happiness, and who feel for it and for you a gratitude of which they take this means to speak.

To have created a house in which learning and the arts of music and of talk were equally at home is to have created as fine a thing as men are capable of making. The houses famous for music and for beautiful speech, and for the company of those who love these things, are not numerous in the history of any time. Dumbarton Oaks which, with an unexampled generosity, you have now given to a great university for the uses of scholarship was such a house, and we who shared it sometimes with you cannot watch your giving of it without these words of our appreciation and our praise.

Some of us remember one thing of this house and some another. Some of us when we think of it, think of the swimming pool by the white azaleas, with Siposs on the bank tossing Senators about like beanbags and below, in the sunny water, the brave and the fair rising and falling on the tidal wave of Ronald Lindsay’s plunge. Others remember the candles and the fireflies beneath the moon-filled oaks and men of many languages and many lands talking of things that had been or that should have been or were to be. Some think of the winter evenings in the music room, the huge logs burning and the gentle light reflected from the great painted ceiling. Some of Stravinsky’s Dumbarton Oaks Concerto, or of Ernest Schelling, or of Nadia Boulanger building out of sounds and silences the perfect architecture of her mind.

But whatever we remember of this house—whether the music or the voice of Royall Tyler in the winter dusk, or the boxwood alleys or the ficus vine or the grey and golden salon with its yellow rug or the galloping bronze house, or El Greco’s blue robed angel—whatever we remember of this house is good and sharp and lasting, as all art and learning is. And for these things we write you now our admiration and our thanks.

January 1941