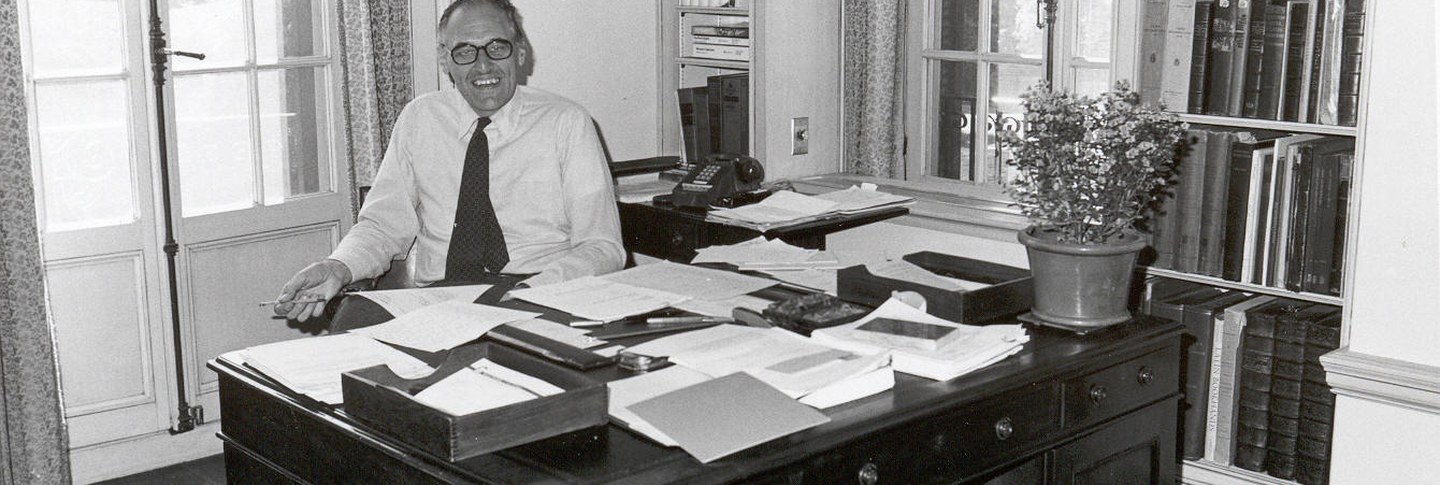

Director Giles Constable in his office, 1978.

Giles Constable, professor of medieval history at Harvard and Princeton Universities and later the chair of the School of Historical Studies of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, was director and professor of history at Dumbarton Oaks between 1977 and 1984. Constable was the first director appointed from the ranks of Harvard’s medieval departments, a tradition that would continue thereafter to the present day. Although he had been one of the ten members that authored the “Report of the Committee on the Future of the Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, 1970,” during his directorship at Dumbarton Oaks, he disbanded the permanent faculty while inaugurating the tradition of Dumbarton Oaks professors in Byzantine fields at Harvard University. He also left vacant the position of director of Byzantine Studies, which would remain unfilled until 1991.

Constable also brought about considerable changes to the physical plant of Dumbarton Oaks: he had the buildings air-conditioned, he had the third floor of the main house reinforced in order to install shelving for part of the library’s holdings. This, as well as the installation of compact stack shelving in the basement, came about after plans for a subterranean library under the North Vista in the gardens met with insurmountable opposition.

Also during Constable’s tenure at Dumbarton Oaks, a period of double-digit inflation that began to decimate the institution’s endowment, the question of the institution’s viability at its location in Washington, D.C., was once again raised. The unfounded but common perception that the research programs and their libraries would be moved to Harvard University was the principal reason for Constable’s 1978 address at the Byzantine Studies Conference, “Dumbarton Oaks and the Future of Byzantine Studies.” The following are excepts from that address:

There is no need to emphasize to this audience that Dumbarton Oaks is in its inspiration an almost ideal example of enlightened academic philanthropy. It exists to preserve not the memory of the founders, or only their personal vision, generosity, and taste, but to serve the scholarly areas in which they believed and which they wished to see flourish. . . . The intention of the founders [was] that “the Mediterranean interpretation of the humanist disciplines” should predominate at Dumbarton Oaks and that gardens and trees have their place in “the humanist order of life.” The physical beauty at Dumbarton Oaks—the house, gardens, collections, and music—were for them an integral part of its scholarly life.

This ideal of a Medicean Academy, with a group of scholars reading, writing, and discoursing in idyllic surroundings, has proven almost impossible to achieve at a time when most people, including many scholars, reject the assumptions of seclusion and privilege upon which it was founded. The great problem at Dumbarton Oaks, therefore, is to find a framework that will preserve the essential vision and purpose of the founders in a way that is adapted to the realities of academic life today and that will make the greatest possible contribution to the areas of scholarship it was founded to serve.

The weaknesses of Dumbarton Oaks have been diagnosed almost unceasingly since its inception and have baffled a generation of scholars and administrators. Both externally and internally, the main problem has been isolation. As early as 1946 the Director of Studies warned that, “A research institution in semi-isolation can develop dry-rot with surprising rapidity.” The Director of Studies in 1957 wrote that there was a real danger “of the institution disintegrating into a collection of hermits’ cells” and that the scholarly output at Dumbarton Oaks would “continue to be not essentially different from that which might be expected from a comparable number of specialists working separately in different places.” Again in 1970, the fact “that the faculty is isolated from its natural academic environment” was cited as the “prime cause of unrest and frustration” at Dumbarton Oaks. This isolation, both of individuals within Dumbarton Oaks and of the institution as a whole from other centers of intellectual activity, has long been seen as a danger at Dumbarton Oaks, therefore, but no fully satisfactory solution has been found.

It is hard to believe that only twenty years ago the Director of Studies deplored the “overall shortage of young Byzantinists” and lack of qualified applicants for fellowships and jobs. The shoe is now on the other foot, and the shortage of professional positions has heightened the tension and competition among young scholars and driven out some, while frightening off others, to a point where the continuity of teaching and research in the future is a matter for serious concern.

No special knowledge is needed to realize that in no part of the world today is the past more part of the present than in the eastern Mediterranean. Byzantinists have a unique opportunity to establish the importance of their courses in area programs of Mediterranean and Middle Eastern studies, where an understanding of the modern situation requires a knowledge of the past and where the central position of Byzantium in a view of the medieval world stretching from the Persian Gulf to the Atlantic can be asserted. This is an opportunity both to establish the need for Byzantinists in teaching the undergraduate curriculum even at small institutions, and, no less important, to bring teachers and students into touch with work going on in other fields. . . .

In order to preserve the vitality of its own interior intellectual life, [Dumbarton Oaks] must always be looking outwards, responsive to the needs of the society in which it exists and to the constant stimuli of openness and variety. Dumbarton Oaks can never be a large institution, with built-in variety. Perhaps, indeed, it should be smaller than it is now. All the more, therefore, it must always be open not only to serious scholars working in its fields of interest but also to the new ideas, perspectives, and techniques that they can bring. . . . By bringing together colleagues, by listening to what they have to say, and by developing structures to learn from them, it should be possible to assemble at Dumbarton Oaks a group of scholars who will truly benefit from all its resources and make it, as its founders intended, into a “vital center of distinguished scholarship, a useful ornament to Harvard University, and a continuing haven for seekers after Truth.”