By Julia Ostmann

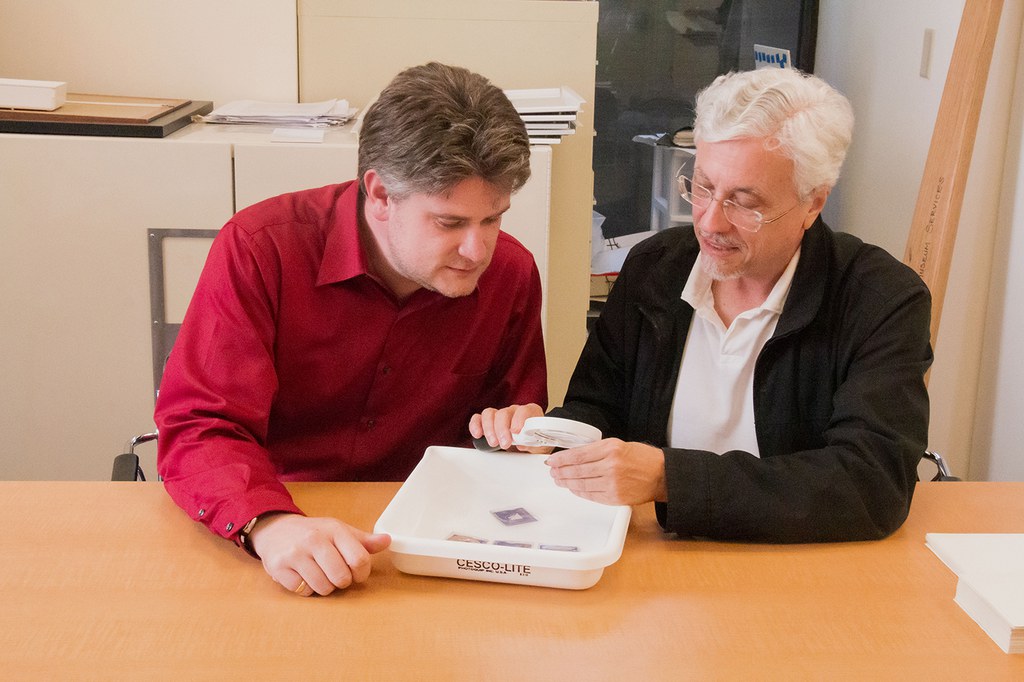

“This one I thought was quite lovely,” said Father Joachim (John) Cotsonis, gazing at the over-800-year-old stamped lead disc in his fingers. “A Virgin and Child, where the Child’s foot crosses the border here, almost as if it’s coming into our space.”

Stark basement lighting doesn’t dim the imaginative design on the Byzantine seal—a device for securing documents while broadcasting your trustworthiness and status. “It’s quite beautiful,” continued Cotsonis, a leading expert on Byzantine lead seals and their imagery. “It makes the image very immediate for the owner, and then for whoever would have received the document this was attached to.”

This particular seal (BZS.2019.007) comes from a major recent acquisition aimed at strengthening the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine seal collection, one of the most comprehensive in the world. The 12 new lead seals contain underrepresented family names and unexpected early military ranks. From bureaucrats to the deacon of Hagia Sophia to soldiers, they belonged to a wide swath of people from the 8th through the 14th or 15th century.

Several seals feature exquisite designs: a rare eagle wearing a jeweled collar, wings spread wide; an unusual cross from the end of the empire; military saints with millimeter-sized chain links. Who could make sense of these uncommon images?

Enter Cotsonis, an art historian and the director of the library at the Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology. He accepted an invitation to evaluate the new acquisitions and teach students in the Coins & Seals Summer Program about the iconography of Byzantine seals. “Seals hold the largest number of surviving images for Byzantine studies,” he says. “There are literally thousands of them. It’s a very important resource and body of material.”

On another of the 12 seals, Saint George and Saint Theodore stand either side of the disc wearing intricate military costume (BZS.2019.012). The inscription reads, “Lord help Melias ostiarios,” indicating this seal belonged to an imperial palace servant and eunuch. How could a servant afford to commission custom art? “There are some good salaries that go with being a palace servant,” says Jonathan Shea, assistant curator of coins and seals. “And when people are appointed to certain positions or certain titles in the court or the state, they have to give gifts out to the palace servants. So if you are the right guy in the right place, every time someone else gets promoted, you get a present.”

Cotsonis pointed out another seal decorated with an eagle (BZS.2019.002). “There are not too many seals with images of animals,” he said, noting that the Islamicizing motif became slightly more popular in the 10th century. Eagles symbolized the divine emperor in the classical Roman tradition, a connotation carried into the Byzantine period but associated instead with the divinity of Christ. The standing bird with wings spread reminded Cotsonis of eagles on textiles from the Middle Byzantine period.

One of the other recent acquisitions is a rare seal from the very end of the Byzantine empire, when loss of territory to the Ottoman Turks significantly reduced the number of seals struck (BZS.2019.014). Most surviving seals from this period belonged to emperors or patriarchs, but the inscription here suggests the owner was neither. Though damaged, an image of the cross—unusual for the 14th or 15th century—also appears.

“Seals are often not the prettiest images, unlike a manuscript or an icon or a wall painting that is so beautiful to look at,” says Cotsonis. “But because you have thousands of images, and in many cases you also have thousands of names and officeholders and ranks attached, there’s a lot of material to study the social history of the use of these sacred images. You can’t do that as easily in other media.”

For example, research from seals revealed that the most popular saints in Byzantium were the Virgin and Saint Nicholas. The new acquisitions in particular offer very fine and sometimes early examples of larger trends, rounding out what is already known in the collection and enticing scholars to dig deeper.

“Byzantine seals are almost like a little snapshot of the people who made them,” says Shea. “And we don’t have snapshots of many Byzantines.” People considered unimportant and left out of standard histories of the period—palace servants, soldiers, notaries, monks—still had seals. This is why the 17,000-strong seal collection matters for Byzantine research. “You put lots of unimportant people together, and you can start saying things about unimportant people.”

Julia Ostmann is postgraduate writing and reporting fellow at Dumbarton Oaks. Photos by Elizabeth Muñoz Huber, postgraduate digital media fellow.