By May Wang

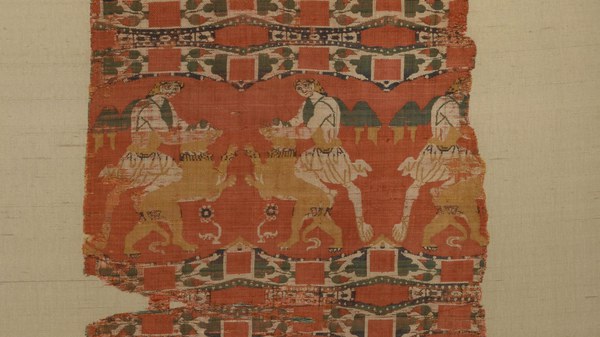

“Wow this one is beautiful,” reads the message that has popped up in the Zoom chat box as Elizabeth Dospěl Williams, associate curator of Byzantine Collection, holds a deep blue silk fragment with Amazons aiming arrows at felines (BZ.1946.15) as close to her laptop camera as possible.

It’s one of several textiles Williams has pulled out of storage or off display for a virtual visit with the twenty-one students of Brad Hostetler’s Introduction to Islamic Art and Architecture class. So many facets of traditional learning have become more challenging as schools and universities have largely transitioned to virtual instruction this fall, but one silver lining has been the ability to enrich the virtual learning experience by bridging the distance between museum collections and students around the world with virtual visits. “I’m always looking for something to bring variety to the semester,” says Hostetler, previously a 2015–2016 junior fellow in Byzantine Studies and now assistant professor of art history at Kenyon College. “Visits like this allow students to see real objects in real life tied to these texts we’ve read.”

In a typical semester, the galleries might host a handful of university tour groups, and another dozen or so advanced-degree students might have the opportunity to visit object storage. But with in-person activities on hold for the time being, Williams and Associate Curator of Coins and Seals Jonathan Shea saw an opportunity to experiment with the class visit format, embracing virtual means of communication as the pandemic continues. So, in late summer, they sent out a dispatch to their colleagues in Byzantine and medieval studies near and far to offer the collections and their expertise for the unprecedented fall term. Many were previous Dumbarton Oaks affiliates already attuned to the depth of the collection. “I had initially thought to limit it to ten visits,” said Williams. “But I just couldn’t say no [to more], because it’s such a time of need that, if we can do a service for people, professors, but above all for the students, then it’s our responsibility to do so.” To date, Williams has led nineteen virtual storage visits, bringing the collections into the Zoom classrooms of 275 undergraduate and graduate students.

Tailored Experiences

Bringing the vaults of the museum to the virtual classroom is no small feat, either. Williams prepares several objects for each visit—sometimes multiple visits in a day—and often suggests bibliographies and readings for students to prepare for the visit. She also works closely with each instructor to ensure the session is relevant to and coherent with the rest of the course. “As a curator, I often feel like I’m dropped into the course without really understanding the context of it, so I much prefer being integrated and understanding the needs of the professor and of the students,” explains Williams. To that end, she works with professors to understand the course content in the weeks that precede and follow their class visit. “It becomes very bespoke for each class,” she says.

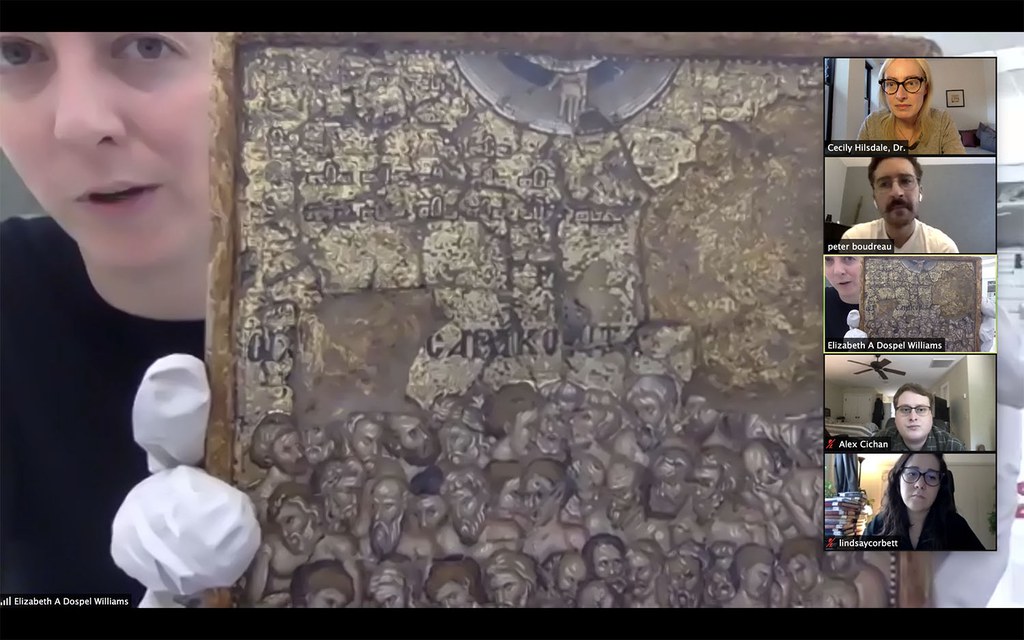

Cecily Hilsdale, a 2001–2002 junior fellow in Byzantine Studies and now associate professor in art history and communication studies at McGill University, took Williams’s offer as an opportunity to enrich the studies of her graduate students at all stages of their program. Their visit was tailored exactly to her students’ interests: Hilsdale asked each of her five students to browse the museum catalogue and choose their favorite objects. Then, she and Williams worked together to select objects to pull from storage for their visit, which was “a way of building a sense of community, especially for students who are off writing their dissertations, which can be a lonely, isolating time,” notes Hilsdale. It was also an opportunity for first-year graduate students to “get to know their older siblings,” so to speak, by giving them a project to work on together and to get to know each other, which takes on even greater importance in the context of remote teaching and learning.

During the visits, Williams broadcasts via Zoom from on-campus collections storage amidst tables covered with the pulled objects. She holds up each piece in turn, sometimes supported on an easel to pass over with a bright light, other times pushing it as close to her laptop camera as possible to give a sense of the detail. Her real-time interaction with the objects, though disseminated virtually, brings the objects to life, even for those that are often on display. “Being able to see how [the objects] changed when they rotated, opened, or the lighting shifted has changed how I think about several of these works,” says Emily Silbergeld, one of Hilsdale’s PhD students, and the ornate metal surface of the Riha Flabellum “caught and reflected the light unevenly and fluidly” in a way that brought Peter Boudreau, another of Hilsdale’s doctoral students, “closer to the flabellum’s original context in a dim candlelit church interior.”

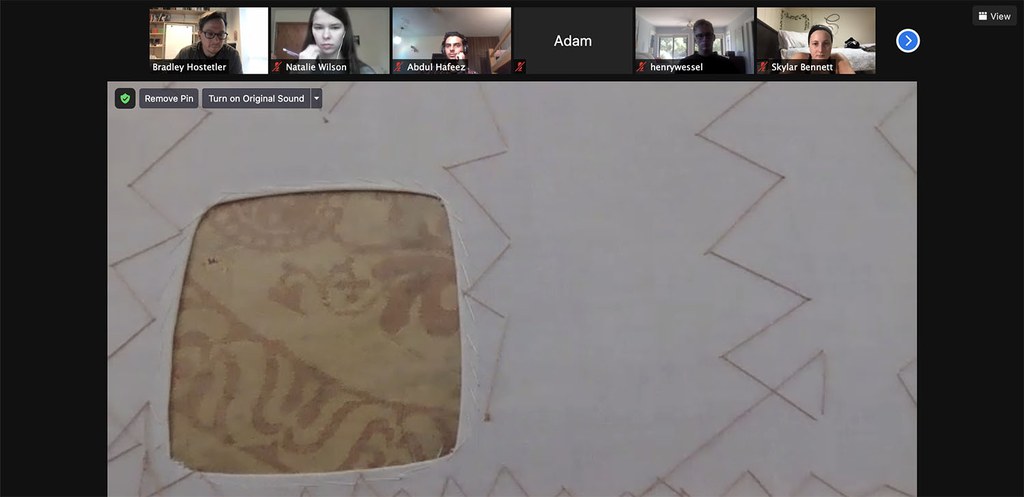

Williams’s explanations shed light on the life of the object in the museum, too. Many textiles, for example, are stitched to canvas stretchers for easier exhibition. During Hostetler’s class visit, in addition to explaining the iconography and importance of the textiles themselves, Williams turns the stretchers around, revealing a haphazard network of stitches used to secure the fragments to the stretcher. On the backside of a two-color silk fragment, a gap has been left in the canvas to offer a peek into the inverse of the pattern visible in the mounting. “The conservator made the decision that this [white motif on red background] was the front of the textile,” Williams explains, offering insight into the conservation and curatorial decisions that go into displaying these pieces.

Encountering the Collections in New Ways

The visits also offer a creative way to support Dumbarton Oaks’ dedication to the humanities beyond the physical campus. Hilsdale describes it as “extend[ing] the spirit of being in an academic community at DO,” fostering a vibrancy and richness vital for scholarly work. She lauds the visits as an opportunity for students to approach the collections more broadly: instead of accessing the collections while singularly focused on the specific research question of a fellowship or grant, virtual visits and demonstrations like these are a chance to encounter pieces in a more exploratory way.

The uniqueness of the visits is particularly germane for younger students, providing a peek inside parts of the museum not typically available to undergraduates. At the start of Hostetler’s class visit, Williams informally polls the group for how many of the students have ever seen museum storage spaces—only a few students were connected to someone able to offer that type of access. Hilsdale and Hostetler both note the challenge of bringing classes from outside the DC area to Dumbarton Oaks, but the virtual learning environment has collapsed those distances and offered an even more intimate experience in some ways than a typical in-person visit might. “When we make class visits [to other museums], we’re in the galleries,” says Hostetler. “This visit offered such a rare view of the museum setting from the storage room.” In addition to bringing the students closer to the art, he says, “I hope it opens up the students’ eyes even more to questions like, what do museums do? What does it look like behind the scenes?”

The visits haven’t just been educational for the students, either—it has been an opportunity for Williams and her team to assess the collection’s significance to students and scholars. Julianna Kardish, a humanities fellow who has assisted in many of the visits, notes that students in multiple sessions “bridged Byzantine history with contemporary concerns like wealth, class, race, and labor.” Among scholars, Williams explains, “what other people are asking of me tells me a lot about the state of the field and how the collection is useful to the scholars who are really at the forefront.” She has fielded requests for a variety of topics and eras that speaks to the versatility of the collection. There are the survey courses in art history, often in Islamic art like Hostetler’s class, as well as the more specialized, such as medieval theories of the body—considered through the jewelry collection—or material culture considerations of wealth, to name a few.

Williams enigmatically ends Hostetler’s class visit by asking if it is time for the “mystery item.” Unrelated to the session’s focus on textiles, Williams pulls out the St. Demetrios reliquary, which is often on view but not animated like this. Hostetler narrates the intricate steps of opening the locket for the students—who have remained online past the official end of class—as Williams unwinds the hand-carved screw and opens a set of “doors” within to reveal a St. Demetrius lying in repose. The students lean in closer to their respective screens to inspect the inscriptions, icons, and mechanics of the reliquary.

It’s a moment that encapsulates how visiting the vaults of the museum virtually still captivates in unexpected but enriching ways. “I want people to have an experience of handling art, understanding the importance of looking at artwork,” says Williams. “It’s a lifelong skill they can bring with them beyond whatever fact they learn in their class.”

Explore the Byzantine collections both on view and in storage, and examine the Byzantine textiles close up in the Catalogue of the Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection.