By Rebecca Krinke

In the summer of 1921, Beatrix Farrand began to think about how she might go about designing the landscape and gardens of Dumbarton Oaks, the home of Mildred and Robert Bliss in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, DC. In this centennial year of the gardens at Dumbarton Oaks, “multiple perspectives on anniversaries, growth, and change in the gardens” are being explored. Thinking about Farrand and her work from the perspective of 2021 provides a useful mirror, and what I saw in the mirror had much to reveal about the role of women in landscape architecture and the garden throughout history.I was introduced to the concept of “mirror wisdom” through an essay by Joanna Macy, “Entering the Bardo,” in Emergence Magazine, July 20, 2020.

Women’s Roles and Rights and Women in Landscape Architecture

1921

In 1921, women in the US had nominally been able to vote for less than a year. The 19th Amendment did not, however, curtail individual states from making their own restrictions; Black women would fight for decades after to win the right to vote. Race, class, ethnicity, and marital status all shaped where a woman could work and what opportunities she might access. Choices were restricted by law and by societal norms and women were encouraged to dwell in the domestic sphere. It is interesting to note that legal protections for working mothers and pregnant women didn’t exist until 1978.

Farrand grew up in a wealthy, socially connected New York family she often described as “five generations of garden lovers.” Their summer home, Reef Point, on Maine’s Mt. Desert Island and Farrand’s life in the gardens there inspired her career choice as a professional designer of landscapes. Landscape architecture was named and positioned in the contemporary American sense by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1863, but landscape architecture was not an official degree program in universities yet. Nor did women have the same avenues for education as men, but opportunities were growing. Farrand, as with all the early practitioners, had to design her own education. Her family connections enabled her to seek out Charles Sprague Sargent, founding director of the Arnold Arboretum, as a mentor and teacher. Farrand wanted additional technical and engineering skills, so she hired Professor William Ware from the Columbia School of Mines to tutor her. She opened her own office in 1895; projects followed, and she began hiring staff. Over the course of her career, she hired only women to work in her office, although she collaborated with men as architects, gardeners, and construction laborers. Farrand was one of the eleven founding members, and the only woman, of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) in 1899. Marjorie Sewell Cautley, Ellen Biddle Shipman, Marian Cruger Coffin, and Amy Cogswell, among others, also led well-known landscape architecture practices in that era.

2021

Globally, we are living at an inflection point of interrelated crises—ecological, racial, social, political, and spiritual. In the US, democracy and voting rights are under assault, and Black women continue to be leaders in that fight for equity. There are now more women than men in landscape architecture programs, but the percentage of women as licensed landscape architects or principals in firms is only about one third that of men. There are several women-led practices with a national/international presence, among which Martha Schwartz; GGN, led by Kathryn Gustafson, Jennifer Guthrie, and Shannon Nichol; Andrea Cochran; Mikyoung Kim; SCAPE, led by Kate Orff; Agency, led by Gina Ford and Brie Hensold; and Sara Zewde. The number of women faculty members in the field has gone up dramatically, from only nine full-time faculty in the 1980s to representing 39% of all faculty positions in landscape architecture in 2021.Samantha Solano, email to the author, July 13, 2021. Solano also included this information: “Women represent 45% of all tenure-track positions, and of the total tenured positions, 35% are women—where 70% of those are associate professors, and 30% are full professors. Men outnumber women in administrative leadership roles by 2:1.” This data was compiled from university websites through The VELA Project (Visualizing Equity on Landscape Architecture) since CELA, ASLA, and LAAB do not collect or report this information.

But landscape architecture is still overwhelmingly white. Recent initiatives focused on equity include the Black Landscape Architects Network; WxLA, focused on “advocating for gender justice in landscape architecture”; and in 2020, ASLA held their first Pride events.

“The Garden” and the Gardens at Dumbarton Oaks

1921

“Appropriate places” for women in the early 20th century were seen as the domestic sphere, and the space of the home included the garden, flowers, painting flowers, and botanical illustration. Farrand highlighted the role of plants in her work, choosing as her title “landscape gardener” from the British tradition. She did not believe that “architecture” should be anywhere in the title. Her first designs were residential gardens, some for neighbors of her Reef Point family home.

Farrand’s practice valued relationships: with clients, plants, the garden, and the garden makers. In contemporary practice and education, collaboration is seen as essential, between designers and communities as well as with the local wildlife and environment.

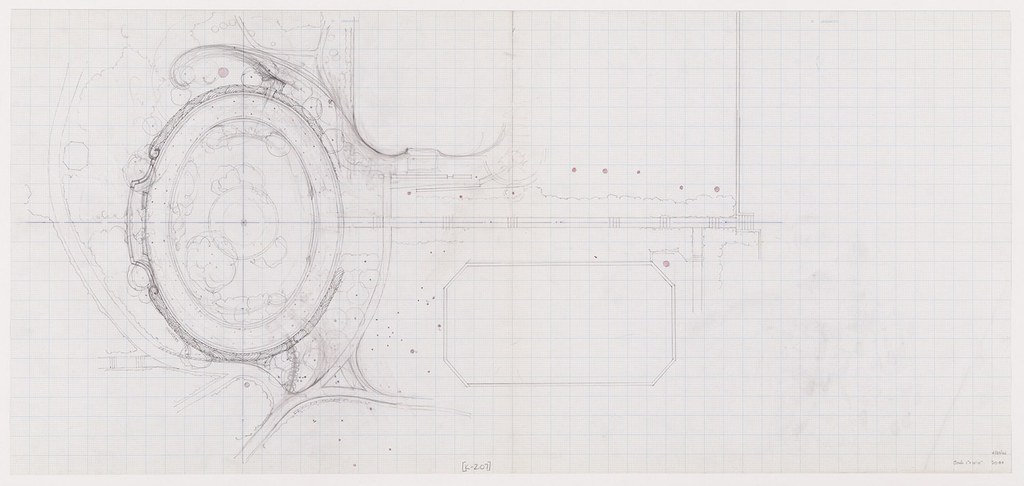

During my first visit to the Dumbarton Oaks Gardens, I had a strong sensation of going through the looking glass and entering a wonderland imbued with a rare personality. The series of linked garden rooms cascading down the slope felt both logical and mysterious. It was easy to get lost—not frustrated or bewildered; rather, I was enticed to wander and discover. Descending the narrow Box Walk into the Ellipse took my breath away. This garden has an “aura” as Walter Benjamin described it—a presence that must be experienced in time and space; it is a work of art, and I was heartened to see the Centennial is investigating “the garden as a work of art.”

2021

Landscape architecture’s relationships to plants, the garden, and the residential setting has been characterized by flux: sometimes the relationship is seen as fundamental and powerful, but often also seen as domestic in scale, too much plant focus and not enough design focus. Another way to say this is that gardens have been seen as a female space, an amateur space, a space where landscape architects did not want to tread; the dreaded “what should I do with the yard?” still hovers over the profession.

Martha Schwartz is internationally known as an innovator of the garden and of landscape architecture. Her Bagel Garden of 1979, made in her front yard while a student at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), stunned the professional world when it was put on the cover of Landscape Architecture Magazine. The letters to the editor that followed were both outraged and excited by her temporary, serious-humorous, artful parterre garden, made with low-tech unusual materials purchased down the street. Schwartz’s 40 years of practice shows committed and generative work with art, land, and climate change. She has been teaching at the GSD since 1987 and was finally awarded tenure in 2007, becoming the first tenured woman in the Department of Landscape Architecture (founded in 1900). In 2020, Sara Zewde became the first tenure-track Black woman professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture at the GSD.

Other women in landscape architecture who have led decades-long award-winning practices include Pamela Burton (45 years), Topher Delaney (35 years), and Andrea Cochran (20 years plus).

Dumbarton Oaks Garden and Landscape Studies began in 1972 and is now led by Thaïsa Way, PhD, professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Washington, the second woman to direct the program. She is leading a five-year initiative “foregrounding those who have so often been silenced, including women, LGBTQ+ people, Black and Indigenous people, immigrants, and working-class laborers.”

Time and Gardens

1921

Designing, grading, planting, and gardening were integrated in Farrand’s mind, and she exemplified this attitude by spending a great deal of time on site with Dumbarton Oaks gardeners and contributing to the selection of the garden’s superintendents. In 1941, when the Blisses entrusted Harvard University with maintaining the house and land as a center for scholarship in the humanities, Farrand began her Plant Book for Dumbarton Oaks. This would serve to outline her design intentions for each of the garden spaces and how to maintain them over time, with a priority on adaptable planting choices rather than the rote replacement of plants.

Farrand was not afraid of looking at the future; she donated her Dumbarton Oaks archives to Dumbarton Oaks/Harvard and knew she was sending “a formidable collection. . . . You will of course want to make this material . . . available and useful to students of Landscape Architecture” (B:BF 1950.04.1). As she phased into semi-retirement, she established Reef Point as a teaching and learning center, and when this was no longer tenable as a long-term proposition, she had the courage to dismantle her gardens and move to a nearby cottage, creating her last garden in her new domestic space.

2021

The garden as a typology is now amid another wave of appreciation and investigation by female, male, and nonbinary landscape architects, as well as by people from all walks of life who are reclaiming the garden as an essential part of contemporary life. Gardens are productive spaces, community spaces, spaces of habitat and respite, places of healing and contemplation.

New practices remind me of what Beatrix Farrand was committed to: plants, people, relationships, growth, and change. For example, Phyto Studio, cofounded by Claudia West, Melissa Rainer, and Thomas Rainer, has deep horticultural-ecological expertise. They work closely with clients, growers, on-site with contractors, and with maintenance (can we call it gardening?) in place from the beginning. West and Thomas Rainer cowrote Planting in a Post-Wild World to bring their approach to a wider audience. Julian Raxworthy’s recent book Overgrown: Practices between Landscape Architecture and Gardening addresses one of landscape architecture’s “most repressed subjects”—the garden and the process of growth as the medium of landscape architecture. As a landscape architect, gardener, and academic, Raxworthy argues for their integration. Contemporary practices that embrace the garden and, interestingly, were cofounded by women and men include Ten x Ten (Maura Rockcastle and Ross Altheimer) and Unknown Studio (Claire Agre and Nick Glase).

Mirror Wisdom: 2121

What could the Dumbarton Oaks of 100 years from now be?

If carbon emissions are not drastically cut, DC’s climate is predicted to feel like Mississippi’s does now: hotter with more intense storms, increased flooding, and sea level rise that could raise the rivers 11 feet by 2100, putting much of the low-lying city underwater. Dumbarton Oaks is 125 feet above sea level, so while it is slightly more protected topographically, climate change will have major effects on plant, animal, and human life.

Hopefully, by 2121 the country and planet have addressed carbon emissions; have faithfully worked on and are staying vigilant to just, equitable, and healing relationships between each other and the earth; and humans are living at a more enlightened level around the globe.

What if gardens were or could be an important driver in this? Perhaps the starting point was in 2021, when, emerging from a year of pandemic lockdown, we were perhaps able to work at a different pace, learned to garden or cook, and outdoor spaces were the safe spaces. Now we can more safely gather again, and what better place than our gardens? They touch every aspect of life: food, habitat, respite, aesthetics, and art that can assist us in seeing, questioning, and understanding more of our human relationship with the earth. In my case, I am returning to the garden in my teaching and hybrid practice. It’s time.

Rebecca Krinke is professor of landscape architecture at the University of Minnesota. She has a multidisciplinary art-design practice that works across sculpture, installations, public and site-specific projects, and social practice. In broad terms, all her ongoing work deals with issues related to place, emotions, memories, and dreams. Krinke has designed both permanent and temporary contemplative and commemorative spaces; her published works include Contemporary Landscapes of Contemplation (Routledge, 2005). Krinke’s current writing project is a coauthored book on the art of Char Davies.