As Islamic influence spread across western Asia and northern Africa, Christian writers in medieval Europe began to ask questions that their Byzantine counterparts had begun asking a century or two earlier: Who is Muhammad, and why is he so influential? What is Islam like compared to Judaism and Christianity? What’s the difference between a Christian heresy and a distinct religion?

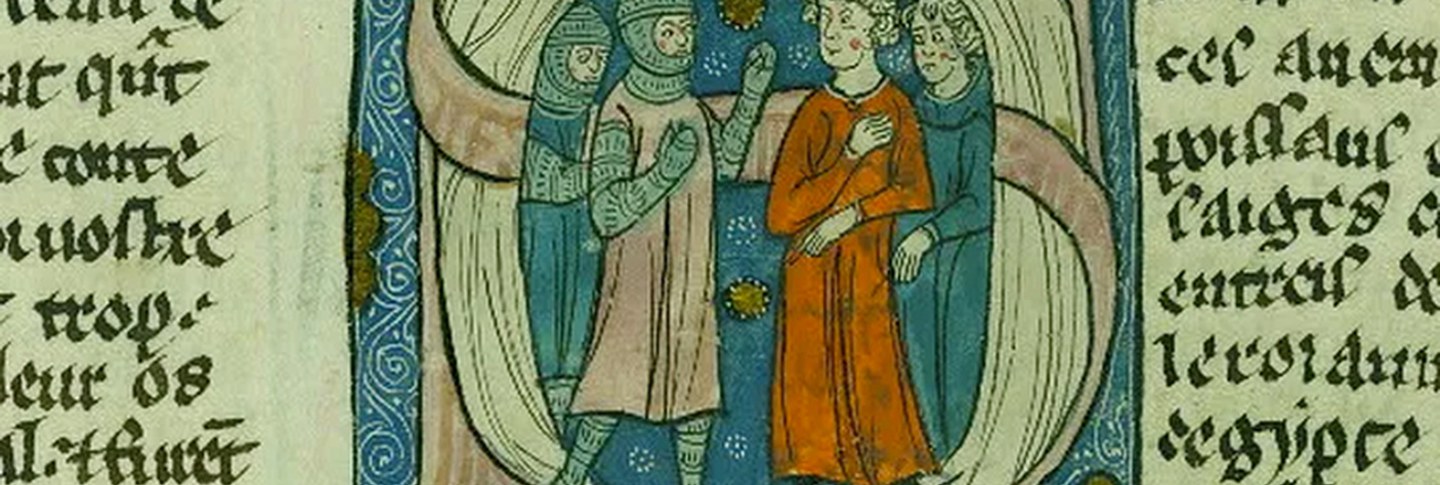

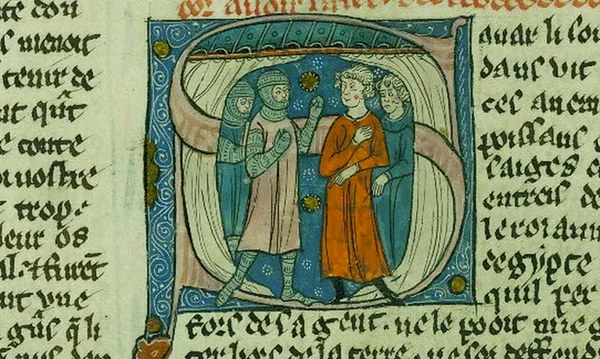

In the Medieval Latin Lives of Muhammad in the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library series (Harvard University Press, 2018), Julian Yolles and Jessica Weiss offer editions and translations of nine Latin texts, written between the ninth and fourteenth centuries, that attempt to make sense of Islamic origins, beliefs, and practices. The Latin treatments of Muhammad’s biographical details often border on the fantastical and grapple with how to place Muslims and Islam within a Christian worldview and context. Particularly since Latin-reading Christians did not have access to the Qur’an until Robert of Ketton translated it from Arabic to Latin in the twelfth century, Muhammad’s biography and Islamic thought were mediated heavily through Christian eyes. This led to portrayals of Muhammad as quasi-Christian or pseudo-Christian, as a heretic or magician who was once a monk or a Catholic or part of a Christian community, and as part of a long lineage of those who corrupt Jewish and Christian scripture for their own gain.

In his eleventh-century poem, the Life of Muhammad, Embrico of Mainz set out to depict the prophet well before his historical context. Embrico placed Muhammad in the fourth century as a Libyan enslaved person originally named Mammutius, who is unintentionally pulled into a much grander scheme: an unnamed Christian magician’s failed attempt to become patriarch of Jerusalem. After this failed power grab ends with the magician being sent into exile, he kills a local Libyan governor with Mammutius’s help and proclaims Mammutius to be a prophet. Almost like a puppet of the mage’s vengeful attempt to get back at the Christian see of Jerusalem for denying him the bishopric, Mammutius is built up by the mage as a wonderworker and seer who purportedly travels into the heavens through epileptic seizures and whose tomb levitates (because of carefully placed magnets). Embrico’s Muhammad is a low-status Libyan figure who is roped into the magician’s schemes and is deceptively portrayed by a heretical Christian as a new prophetic and miraculous figure. In this narrative, Muhammad becomes the prophet not of his own accord, but as part of a heretical lineage that Christian readers of the Life of Muhammad would find both entertaining and evidence that Muhammad was duped even by the “worst” of Christians.

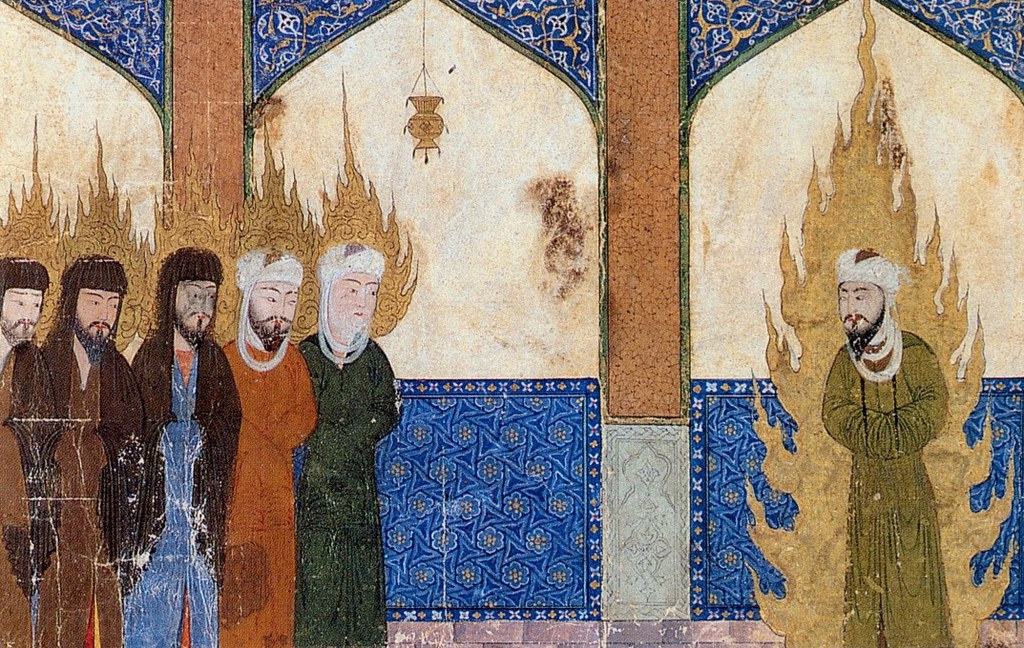

In some of the Latin biographies, Muhammad even learns heretical Christian practices from famed heretics themselves. For example, Adelphus’s twelfth-century Life of Muhammad, a Crusader account that purportedly made its way back to Europe via Antioch, introduces Muhammad not as the protégé of a fourth-century magician, but instead as a fifth-century arch heretic: Nestorius of Constantinople. While the historical Nestorius is best known for controversially rejecting the title of the “God-bearer” (Theotokos) for Mary and proposing “Christ-bearer” (Christotokos) instead, the Life presents Nestorius as a Christian monk who takes on a demonically influenced swineherd named Muhammad as his protégé. Adelphus’s account does not treat Muhammad as a duped figure like Embrico does, but rather presents Muhammad as an active magician and collaborator with Nestorius in rearranging and mutilating the Old and New Testaments in order to produce the Qur’an. Not only is Muhammad treated as a figure emerging out of and deriving from Christian heretical lineages, but even the Qur’an is depicted as a text that is corrupted Christian scripture.

The Medieval Latin Lives of Muhammad is a fantastic lens into how Latin writers and audiences over a period of centuries made sense of an influential religious figure and movement about which few in the West had much direct knowledge. These stories and poems exhibit how writers made sense of Islam through the vocabulary of heresy and biblical literature available to them as they continued to encounter and interact with Muslims and Islamic literature. Rather than treating Muhammad and Islam as innovative, many Latin texts portrayed the religious movement as derivative of their own and as comparable to previous generations of misguided or heretical thought. Such a treatment of Muhammad shows us how thin the line was for medieval Christians in rhetorically distinguishing between a religious movement that was just “bad” Christianity and a movement that was a distinct religious practice and text.

Buy Medieval Latin Lives of Muhammad and browse other Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library volumes at domedieval.org.

Chance Bonar is a PhD candidate in New Testament and Early Christianity at Harvard University and a Tyler fellow with the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library.