By May Wang

“Dumbarton [Oaks] has an opportunity to serve its community and visitors as no other place has,” Beatrix Farrand prophetically wrote to Mildred Bliss in May 1947. The gardens combine “the human and the artistic side with the possibility of lifting the level of outdoor art in its whole neighborhood.” The letter (Garden Archives, B:BF 1947.05.26B), signed by Farrand as Mildred’s “Garden Twin,” advocated for the gardens’ contributions to the nascent institution’s humanistic mission. Farrand, who retired from her position as “landscape gardener” of the estate a month later, was making her case after a successful foray into educating through the gardens that had begun in the fall of 1941—what became known as the Garden Guide Service and continues to this day as the docent-led Garden Tour.

A September 1941 letter (Garden Archives, B:BF 1941.09.08) from Farrand to Superintendent of the Garden James Bryce brims with updates on a “route of parade” for the first garden tours and ideas for the Garden Guide Service offerings. Farrand, in collaboration with the first so-called Garden Guide Anne Sweeney and in consultation with Mildred Bliss, proposed object lessons for visitors young and old to learn to differentiate tubers, corms, and laminated bulbs; making the rose collection more comprehensive “from the point of view of education”; and demonstrations of various other “odds and ends of incidental information [that] interest people even though they may not be horticulturists.”

There was nothing incidental, however, about Farrand’s intentions for educating the Dumbarton Oaks community and public of all ages through the gardens, as correspondence from the Garden Archives in our Rare Book Collection attests. Correspondence between many professionals in the early days of the gardens, including Farrand, Sweeney, Bryce, and Mildred Bliss, are in the process of being added to HOLLIS for Archival Discovery, Harvard Library’s archive database, preserving invaluable insights into the motivation and inspiration underpinning our gardens.

Farrand concluded her 1941 note to Bryce with a favorable update on a report to Harvard University “on the Dumbarton situation,” a report (Garden Archives, B:BF 1941.11.24) in which she passionately argued for the significance of the gardens to Dumbarton Oaks, which had been donated to Harvard just the year before. Farrand conceded that the library and collections are of “paramount importance” to the Dumbarton Oaks scholar. “At the same time[,] the training of the eye to an understanding of outdoor beauty should be recognized as a vital part of the student’s life at Dumbarton Oaks,” she argued. “The composition of the views from the windows at which they may study, the unconscious infiltration into their minds of daily familiarity with garden problems and their solution must be important.”

Farrand found an enthusiastic and empathetic inaugural Garden Guide in Anne Sweeney, a former employee of Anna Blaksley Barnes Bliss, Mildred’s mother. Among various secretarial duties she carried out for the Blisses under the direction of Farrand, Sweeney scripted an hourlong “journey” through the gardens, offering information and anecdotes ranging from “where bulbs come from” to Redouté’s depictions of roses to birds that might be spotted in the gardens. Farrand impressed the significance of the first garden guide role upon Sweeney for multiple reasons, not least of which was that the “mercifully wise and critical mind” of Mildred Bliss, as Farrand described it in an October 1941 letter (Garden Archives, B:BF 1941.10.11), would “undoubtedly hear repercussions of your guide service and we want them to be entirely favorable.” Also, Farrand reminded her assistant, Sweeney was “not just ‘nice Miss Anne Sweeney’ [but] the garden guide for Harvard University.”

Farrand did not envision training an eye for the outdoors to be limited to the learned visiting scholars, either—her 1941 report to Harvard closes with an appeal that the grounds also be visited by “school children, Boy and Girl Scouts, and other like groups,” for “the grounds should be of real value to these students as well as those in residence at Dumbarton Oaks itself.” In correspondence from the early months of the Garden Guide Service, Farrand and Sweeney carefully considered the new program’s appeal to younger visitors. Each month, Sweeney prepared a small exhibit in the Catalogue House, keeping the gardens’ younger visitors especially in mind. “Frankly I think we are right to keep the Catalogue House as small as it is,” Farrand wrote at one point, “because children cannot take in any more than a few things at time,” and it might be more successful to teach them “from an ink-dropper rather than in a tablespoon” (Garden Archives, B:BF 1941.10.21). Indeed, Sweeney reported a group of young students from a Georgetown public school was “perhaps a little young to imbibe much garden lore, [but] they seemed to have a grand time withal and especially the Catalogue House” (Garden Archives, B:AS 1941.10.18).

Farrand’s estimation of the appeal of the grounds, educational and otherwise, was not overstated: in the first year, when the gardens were open to the public just Wednesday mornings and Saturday afternoons, Sweeney reportedly led 1,722 visitors on tours, not accounting for people who visited the grounds without a tour. Farrand was delighted at the warm reception of the tours, writing to Sweeney early on that “you will before long have to strap a megaphone to your countenance and behave like a cheer leader at a football game,” though she advised Sweeney not to overwork herself either (B:BF 1941.10.21).

By 1947, the garden tours welcomed over a thousand visitors on opening weekend alone and over 17,000 visitors during the three-month visiting season. Farrand began to step away from managing the gardens directly that year but made sure to underscore upon her departure the vital importance of the grounds and the Garden Guide Service she and Sweeney had crafted. In a March 1947 letter (Garden Archives, D:BF 1947.03.21) to then-director John Thacher, Farrand wrote that “The garden side of Dumbarton Oaks deserves to be treated as a definitely educational project and not merely as a pretty place in which tourists are allowed to wander. There should be well-kept records, a guide trained in horticulture and botany, and a small library or picture collection to illustrate the work on the grounds.”

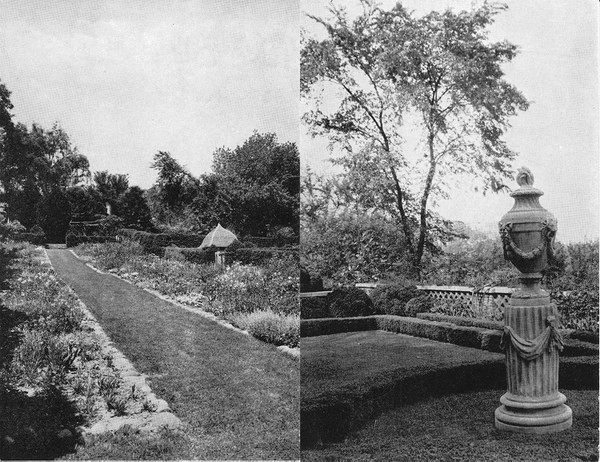

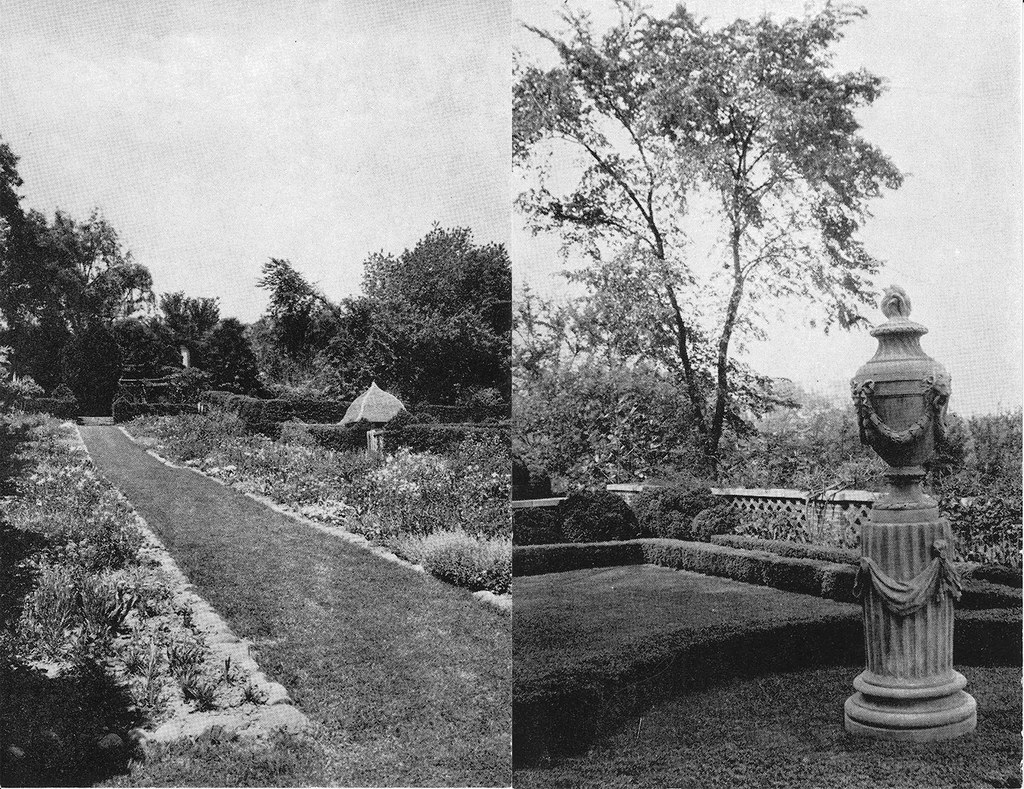

These days, the gardens welcome tens of thousands of visitors throughout the year—39,000 in 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic—and maintain a roster of garden docents who continue to guide thousands of visitors through the gardens. Architectural drawings, sketches, prints, and photographs in HOLLIS Images preserve Farrand’s and Mildred Bliss’s vision for our gardens, and the ever-growing Rare Book Collection furnishes horticultural knowledge and more to generations of Dumbarton Oaks scholars and visitors.

May Wang is postgraduate writing and reporting fellow.