David Gyllenhaal, PhD candidate in history at Princeton University, is a junior fellow in Byzantine Studies. His research report, “The Rebuke Homily: A Neglected Subgenre of Syriac Literature and Some of Its Stranger Implications,” explored the late antique subgenre of the rebuke homily employed at moments of collective trauma from the fourth century onwards.

Q&A with David Gyllenhaal

What is unique about the rebuke homily form?

The rebuke homily is a subgenre of the broader literary form of the memra, which was a poetic format for delivering sermons or homilies in Syriac. What’s interesting about rebuke homilies is that they can be located in a particular social setting. For most memre, we’re not sure when, where, or under what circumstances they were delivered. You might be able to fix it at a particular point in the liturgical year, like Easter, but many other memre are disconnected from an event or moment in time. With the rebuke homily, there are references in the text that make it clear that this homily was being delivered after something bad had happened to the entire community, like drought, famine, and plague. The homily would invoke what I call a catalog of sin, saying the entire community is at fault for this—there is not one segment of the community that is necessarily responsible; the entire community is responsible as a collective. Then the homily would engage the whole community in a penitential ceremony to try and propitiate god, whom they had angered.

How did these enact what you describe as traumatic providentialism?

Rebuke homilies were based on the idea that traumatic events were a punishment from god, which is how they gave meaning to what had occurred. The homilies could channel and articulate the grief-stricken and disoriented energies of the peasantry into positive channels (from the perspective of a priest) for penitential ceremonies and moral reform. It was a good occasion for priests to try to get peasants to stop doing things they had wanted them to stop doing for a while.

This discourse, which I’ve called traumatic providentialism, brought meaning to a traumatic situation by giving it a story based on god’s sovereign governance of all human affairs, basically reiterating that god is in charge. In rebuke homilies, it was a very specific story: everyone had behaved badly, so god had to send Arab raiders or an earthquake as a rod of chastisement, in the same way a father would beat his son or a teacher would beat his students (there was a lot of corporal punishment in late antiquity). There were other forms of traumatic providentialism, such as apocalypticism, or catastrophes could be framed as unmerited suffering that built character or protected the soul. But the idea of divine punishment tends to dominate in homilies delivered to peasant audiences.

How did this subgenre fit into late antique culture at large?

The rebuke homily fits into a larger trend of the Christianization and scripturalization of public life and discourse in late antique culture as a whole.

Christianization largely meant getting peasants to abandon technologies of ordinary life that bishops and priests considered pagan. Peasants had various magical apparatuses for navigating daily life and anxieties around fertility of crops and of people, illness, etc. that had all kinds of pagan trappings long after the people were ostensibly Christian. Peasants were quite happy to mix-and-match Christian, Jewish, and pagan elements—something they frequently did in spells. If priests made the claim that behavior like this prompted a recent earthquake, they were much more likely to succeed in getting peasants to stop doing it.

The scripturalization of public life essentially involved a more elite social register, particularly among people in authority, describing to themselves and to their social inferiors what the Roman Empire was and how it worked. They increasingly used scriptural models to describe the Roman state and its divine significance. That significance had previously been pagan and focused on imperial victory as a lodestar of the Roman state’s vocation. But these rebuke homilies represent an attempt to shift towards a thoroughly scriptural understanding of the Roman Empire: the empire was like the children of Israel, in that it maintained a direct and contractual relationship with god by which it was obligated to follow god’s law. In return, the empire would be given peace, security, and prosperity. But if they didn’t follow god’s law, then god would send the Persians over the border to smash things up.

I’ve appreciated the collegiality of so many people at Dumbarton Oaks. Director of Byzantine Studies Nikos Kontogiannis has been incredibly warm and friendly, and I’ve particularly benefited from talking with fellows like Molly Greene and Emanuel Fiano. I’ve also benefitted from discussions with Mesoamerican specialists at Dumbarton Oaks. Even though we might have nothing in common in terms of languages or architecture or the like, it’s amazing how we often end up asking and answering similar questions about these premodern agrarian societies regarding sacral kingship, urban space, and more.

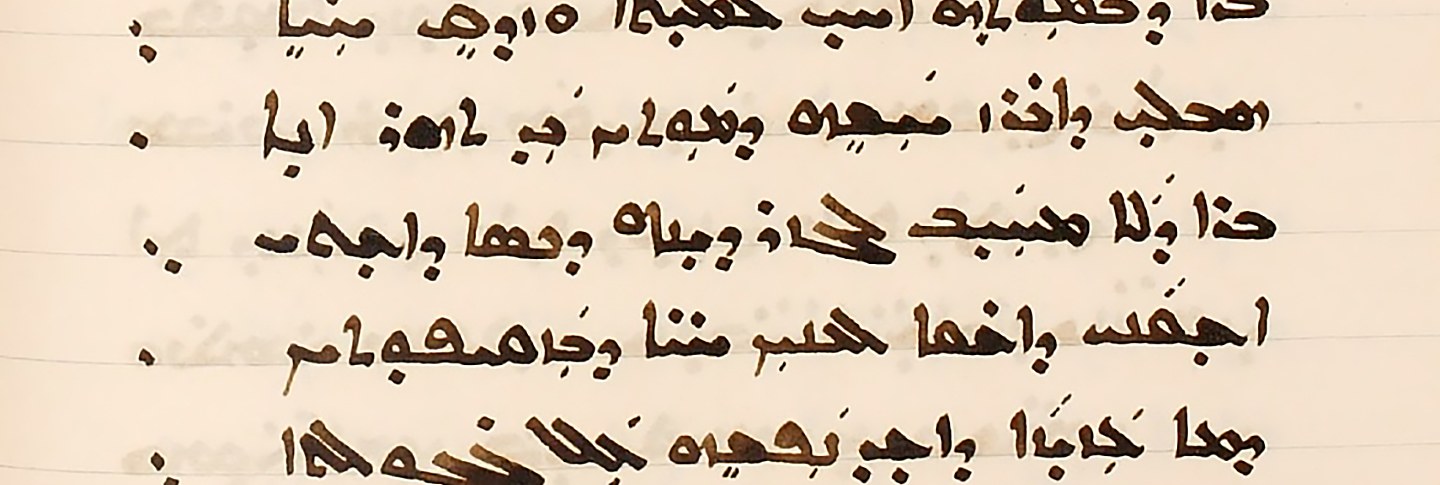

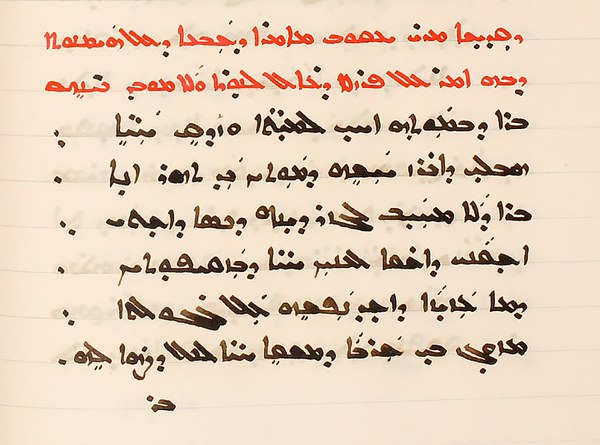

May Wang is postgraduate writing and reporting fellow. Photo courtesy of David Gyllenhaal, CFMM 167, p. 22.