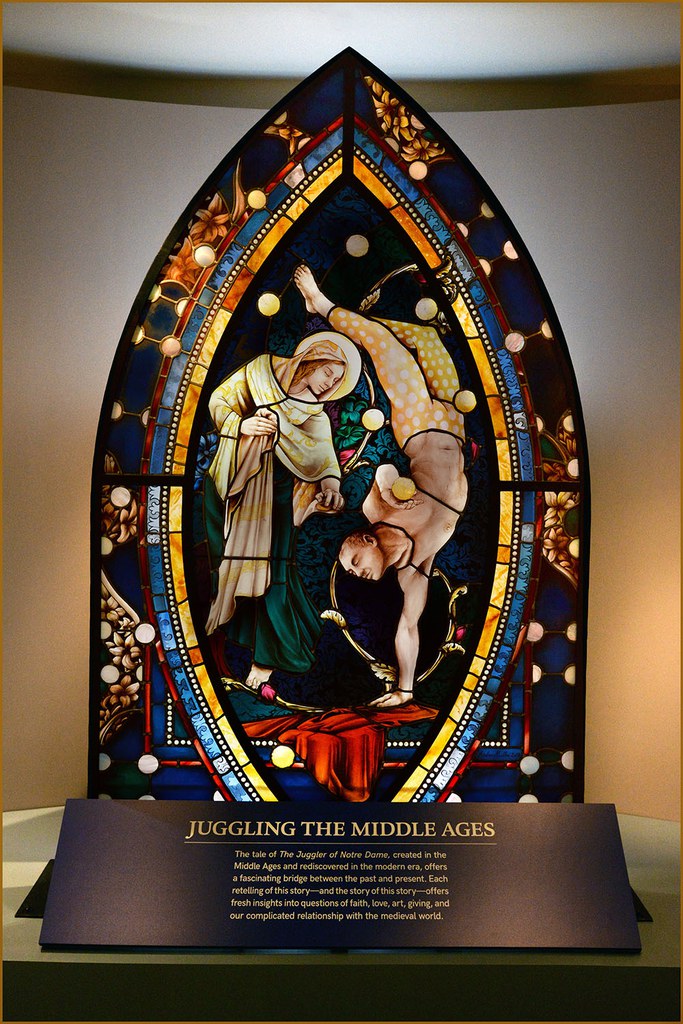

Paris-based stained-glass artist and restorer Jeffrey Miller was commissioned to make the stained-glass window, on display in the museum lobby, for the exhibition Juggling the Middle Ages. The window, which he collaborated on with his daughter—artist Sarah Navasse—and master craftsman Jeremy Bourdois, is the only stained-glass depiction of the medieval story known as the Juggler of Notre Dame and the newest object on display at the museum.

Q&A with Jeffrey Miller

How did you first come to stained glass?

I got into stained glass out of a deep desire to make things with my hands, rather than because I was an artist or wanted to be an artist. My first job after college was teaching history at the American School of Rabat in Morocco. I started a theater program there and really enjoyed directing the plays and making the sets. After two years, I thought I would give working with my hands a try for a while. Just before leaving, a friend who had lived in France for a long time started telling stories about this French family of stained-glass artists he had worked with near Paris. They were working with a stained-glass technique called dalle de verre. The raw material for their windows was one- to six-inch-thick slabs of glass, which were sculpted like prehistoric flint tools, by chipping at them, by hand, with hammers.

Although I was going to be spending the next four months traveling around Europe before returning to the States, I didn’t even consider the possibility of moving there. But then everywhere I went, I was looking at stained glass more and more. Looking at stained glass in the European cities I visited became a reason for this continental pilgrimage. Before flying back to the States, I managed to find the Guevel studio lost in a Parisian suburb. I knocked on the door and asked if I could come and work with them. I met one of the brothers, who actually didn’t even work at the family studio. He said, “great, come on back.” I went back to the States and roughnecked on oil rigs in Louisiana for five months to make enough money to live for a year in Paris and work for this family of artists for free. When I actually did meet the other brother with whom I ended up working, we just hit it off and went to work together, despite the fact that I didn’t speak any French. It was sort of miraculous. I stayed with them for three and a half years and then started off on my own.

Stained glass is popularly associated with Christian visual culture. Is the religiosity of the medium something you think about?

The religiosity of stained glass as a medium doesn’t feel the same in France as it would in the States, even when you’re working in a church. Church buildings are owned by the towns and municipalities, and are maintained because they are part of the country’s cultural and architectural heritage. I guess the idea is that regardless of religion, Art with a capital A is important and part of all French citizens’ cultural heritage, and religious art is still art.

Your studio makes original work, including the window commissioned by Dumbarton Oaks, and works on the restoration of windows that date from the late Middle Ages to the present. Do these two practices intersect or do you see them as separate exercises?

They can be very different things or they can be tightly interwoven. When you go to a fine arts school, the emphasis is on creating, whether it be painting, sculpture, or drawing. Restoration involves working with and learning about art, and learning artistic skills, but the emphasis is not on creating. To give one example, when you restore windows you learn to paint on glass the way people painted on glass 50, 100, 400, and 800 years ago. A cynic might say that’s like learning to type in a college English class. But when I go back and forth between restoration and original work, these two activities nourish each other, and there are always new lessons to be learned. And I’d like to think that restoring windows from such different periods has helped me be more open to creating in different styles.

Without even knowing it, I was strongly influenced by American abstract expressionism, but as I've worked with glass from a wide variety of periods and styles, I think I've become more open to listening to what people want, thinking about what would be good for a given place, and adapting. That was the case for this window at Dumbarton Oaks. It could have been done in any number of ways. But after talking with Jan, it seemed to me that a classic window was the right choice for this show and this story, with just a wink at techniques like dalle de verre.

Do you see your work in contemporary stained glass as a revival of a medieval form? How medieval is your technique?

People often ask, “has the technique changed?” and I jokingly answer, “oh yes, we started cutting the glass with diamond in 1504.” But, more seriously, it has changed a lot. In France, when a town or city commissions a new window for a church, they take public bids from studios. A 500-square-foot window project often goes to the studio with the lowest bid. And whoever bids the lowest price generally uses some technique where they’re not going to spend that many hours on it. You have to prove you’re really good, but also try to be cheaper than the competitors. And that sometimes means not using a technique with lots of little pieces of glass and lots of intricate painting. So that reality has pushed contemporary creations in a different direction, more towards transformation and reinterpretation of medieval forms than reproduction. When medieval cathedrals were built, with all of the involved stonework, roofing, ironwork, sculpture, and painting, the stained glass represented a large portion of the budget. That time-consuming workmanship is never going to be reproduced on a monumental scale today, but it can be “revived” in commissioned work like the window at Dumbarton Oaks.

India Patel is Postgraduate Public Programming and Outreach Fellow at Dumbarton Oaks.