Twenty-five miles northeast of present-day Mexico City, the remains of Teotihuacan still present a remarkable scene, the site’s monumental pyramids and wide, open avenues gesturing at its former significance. One of only two cities in the New World ever to number a residential population of more than 100,000, Teotihuacan’s influence extended widely over Mesoamerica, from central Mexico to as far away as the Maya lowlands.

On October 6 and 7, Dumbarton Oaks held its annual Pre-Columbian Studies symposium, “Teotihuacan: The World Beyond the City.” Organized by Barbara Arroyo of the Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala, Kenneth Hirth of Pennsylvania State University, and David Carballo of Boston University, the symposium was aimed at addressing Teotihuacan’s influence and evaluating the city’s internal organization and external interactions in light of recent studies, research, and data.

Day 1

The first day of the symposium began with a series of joint remarks by Kenneth Hirth and Director of Pre-Columbian Studies Colin McEwan. McEwan emphasized that this year’s meeting moved on from previous thematic symposia, forming part of a series that encompasses “Chavín and its Neighbors” next year, followed by “Mesoamerican-South American Relations Revisited” in 2019 that together emphasize a hemispheric approach. Ken Hirth then offered a brief introduction to Teotihuacan’s art, religion, and architecture, pointing out themes and structures, like the city’s unique apartment compounds, that would appear frequently in the pursuant talks.

Session 1

Michael E. Smith of Arizona State University began the symposium’s first session with a talk that clearly delineated the architectural, social, and political features that made Teotihuacan unique—and those that didn’t. “Teotihuacan: Urban Center, Global City, Mesoamerican Anomaly” noted, for instance, the “normal” presence of a great compound in the city and the “unusual” absence of a ballcourt or obvious palace structure.

New urban design ideas in the city’s layout, Smith explained, included orthogonal planning, organization around a central avenue rather than a central plaza, and the much-discussed apartment compounds, which numbered about two thousand at the city’s height. While apartment-based living arrangements in similarly advanced societies typically served as housing for the urban poor, the spacious apartments of Teotihuacan, replete with patios, drains, and murals, amounted to “luxury housing,” and were the standard in the city. The apartments were thus a sign of another unusual aspect of life in Teotihuacan: it was remarkably egalitarian, with surprisingly little wealth inequality.

The next talk, by David Carballo of Boston University, examined the conflicted scholarly understanding of political power structures in Teotihuacan. Debates on the city’s internal power structures often center around whether the city was ruled by a single sovereign individual or a committee. Carballo’s talk analyzed the city’s art and architecture to suss out the underlying ideologies that might have determined this structure.

Iconographical programs in the city, he explained, tended to “universalize, rather than individualize,” a trait that would have emphasized social roles over the individual. Monumental sculpture in Teotihuacan was often religious, “of and for the gods,” subordinating the human to the divine. Throughout his talk, Carballo discussed the constant reclassification of Teotihuacan—was it a tributary polity? A city-state?—while emphasizing that political “centralization does not equal autocratic or individualistic” rule, but instead should only connote “a powerful government with legitimate authority.”

Kenneth Hirth of Pennsylvania State University followed this with a discussion of Teotihuacan’s urban economy and its interregional interaction. “Teotihuacan Economy from the Inside Out” broke down the levels of production—the household unit’s production of small obsidian, for instance—and described the basic characteristics of the city’s urban economy, including its reliance on a central great compound marketplace and the fact that roughly two-thirds of the city’s population was engaged in farming.

Hirth explained that while a state-managed economic model should not be entirely discarded, external economic interactions were not as tightly controlled as has been supposed—Teotihuacan did not strictly control the export of green obsidian, for instance. Ultimately, Hirth proposed that Teotihuacan’s external economic relations are best explained by a model of corporate commercialism directed by elites.

Session 2

Debora Nichols of Dartmouth College began the day’s second session with a talk on the political, economic, and social factors that structured Teotihuacan’s interactions with its hinterlands: “Early States and Hinterlands: Teotihuacan and Central Mexico.” While these interactions have typically been interpreted as highly centralized, Nichols sought to reevaluate this view using recent surveys and research. The flow of individuals in and out of the city, she asserted, was constantly being affected not only by market-based concerns, but also by natural disasters that forced abrupt settlement pattern changes.

Nichols ended her talk by examining regional administrative centers, sites like Cerro Portezuelo that played a role in the distribution of goods. It remains unclear whether the sites were established by the city, and if their operations were directed by the state. Evidence of ceramic sourcing at Cerro Portezuelo, however, seems to undermine the solar model of economic distribution—wherein all goods flow in and then out of Teotihuacan, directed by an administrative hierarchy—and suggest that Teotihuacan didn’t necessarily direct regional economies.

Gabriela Uruñuela of the Universidad de las Americas, Puebla, next delivered a paper cowritten with Patricia Plunket, of the same institution. “Interwoven Discourses” explored Teotihuacan’s interaction with Cholula, another great Classic period center in Mesoamerica’s central highlands. While we know comparatively little about Cholula and its size and internal organization, an analysis of its art and architecture in comparison with those of Teotihuacan, Uruñuela suggested, can help us understand how the two sites publicly demonstrated power and ideology.

Notably, Uruñuela described the relation between the two sites’ art and architecture as “similar rhythms but different lyrics.” A comparison of the Moon Pyramid and Tlachihualtepetl, the Great Pyramid of Cholula, for instance, shows that both underwent a multistage building period, with similar modifications made in each stage. And in mural painting, Uruñuela contended, the styles of the two cities were so similar that “the themes that each wanted to express resulted in the difference of the murals, nothing else.”

Nawa Sugiyama of George Mason University next delivered a paper cowritten with William Fash of Harvard University and Barbara Fash of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. “The Maya at Teotihuacan?” offered new insights into Teotihuacan-Maya interactions, examining evidence unearthed at the Plaza of the Columns Complex in 2016 and 2017.

While evidence of Teotihuacan influence in Mayan political centers is bountiful, evidence of the presence of foreign dignitaries in the Teotihuacan heartland is much sparser. Describing the exceptions to this state of affairs, Sugiyama discussed the discovery of three individuals with Maya jewelry inside a dedicatory cache at the Moon Pyramid, the second-largest pyramid in Teotihuacan, and mural paintings that depict numerous characteristically Mayan personages and glyphic elements. The largest section of Sugiyama’s talk focused on mural fragments recently discovered at the Plaza of the Columns Complex, exciting finds, Sugiyama explained, that “are so faithful to the Mayan tradition, they are almost certainly the work of Maya artists.”

Matthew Robb of the Fowler Museum at the University of California, Los Angeles, closed the first day’s proceedings with a discussion of curious four-part composite sculptures discovered in Teotihuacan that link the city to contemporaneous sites on the Gulf Coast. “Interlaced Scrolls and Feathered Banners” offered a detailed analysis of the archaeological, aesthetic, and social contexts of these sculptures.

Suggesting that similar sculptures were in fact stone versions of feathered banners, Robb parsed their potential significance, dwelling on the modularity of the markers and positing that they might have been disassembled and moved about on a regular basis. As markers of space, the sculptures might have played a social and ceremonial role—“perhaps we’re dealing with a system where two individual markers had to be brought together from two communities to properly define a space”—while as markers of culture the sculptures signal interactions between Teotihuacan and sites like El Tajín, on the Gulf Coast, and Tikal.

Day 2

Session 3

Wesley Stoner of the University of Arkansas delivered a paper cowritten with Marc Marino of the same institution, opening the symposium’s third section. “Disembedded Networks of Interaction between Teotihuacan and the Gulf Lowlands” focused on the material evidence of Teotihuacan presence in the region.

Dividing manifestations of Teotihuacan-related interaction into five classes—political, economic, ceramic homologues, household religion, and state religion—Stoner and Marino schematized the interactions between Teotihuacan and several sites in the Gulf Lowlands, including Matacapan. Presenting a diversity index that showed greater or lesser assimilation of Teotihuacan culture at each studied site, Stoner and Marino dissected the unitary concept of Teotihuacan expansion, showing how some sites, for instance, exhibited a bias in appropriation, accepting some aspects of influence, like economic interaction, while rejecting others.

Following this, Gary Feinman of the Field Museum of Natural History presented a paper cowritten with Linda Nichols of the same institution. “Teotihuacan and Oaxaca: A Synthetic Reevaluation of Prehispanic Relations” reexamined the city’s ties with Monte Albán, another monumental highland city. The Oaxaca barrio in Teotihuacan was a five-hectare zone that held roughly fourteen multifamily compounds and 800–1,000 people. With a long occupation history beginning around the year 200 and ending with the decline of the city, the barrio, Feinman asserted, is an important point of study when researching Teotihuacan’s external mechanisms of communication and interaction.

Feinman noted that high volumes of exotic pottery have been found in the barrio, suggesting exchange as a raison d’être for the colony. Ceramics, he contended, were used to connect the resident population to Oaxaca through rituals of birth, death, and perhaps even the solar cycle, as evidenced by the presence of ceramic whistles. Residential architecture in the barrio likewise related to contemporaneous architecture in the valley of Oaxaca.

Marcello Canuto of Tulane University and the Middle American Research Institute next delivered a paper cowritten with Marc Zender, also of Tulane University. “The Materiality of Hegemony” sought to investigate interactions between Teotihuacan and the lowland Maya by examining iconographic allusions and inscriptions on stelae. As Canuto explained, bountiful evidence in Maya art and writing suggests Teotihuacan influence throughout the Early Classic period. But how best to characterize this relationship?

In an attempt to answer this question, a large part of the paper considered stele inscriptions that tracked the progress of Siyaj K’ahk’, a Teotihuacan general, into the political landscape of the lowland Maya in the Early Classic period. The inscriptions recorded a variety of event types, including the subordination of local rulers to Siyaj K’ahk’; together, they allow for a general map of his route to be limned, one that manifests as a pipe-shaped path from Teotihuacan to Tikal. The arrival of Siyaj K’ahk’, Canuto and Zender suggested, would seem to presage a newly hegemonic relationship between Teotihuacan and the lowland Maya.

Session 4

To begin the symposium’s final section, Diana Magaloni of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art delivered a paper cowritten with Megan O’Neil of the same institution and María Teresa Uriarte of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. “The Moving Image” delved into the relationship between murals and stucco-painted vessels in order to illuminate the nature of artistic exchange between Teotihuacan and Maya cities. At Teotihuacan, stucco vessels and murals were intimately tied to the apartment compounds, and shared the same color schemes. Magaloni’s paper contended that the stucco vessels constituted a hybrid form integrating ceramics with the mural tradition, capable of transporting the image of the city to distant lands.

Magaloni’s talk also dissected the composition of the vessels, presenting the results of technical analysis carried out at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Most vessels were finished twice, and received their coloring from substances like cinnabar, malachite, and hematite; carbon black was used to emphasize incised lines in the stucco. Overall, Magaloni explained, the artists crafting the vessels privileged color over permanence.

Claudia García-Des Lauriers of the California State Polytechnic University at Pomona next delivered a talk that examined Early Classic period (AD 250–650) interactions between Teotihuacan and the southeastern Pacific coast of Mesoamerica. “Gods, Cacao, and Obsidian” looked at material evidence linking Teotihuacan and coastal sites, including Teotihuacan-style vessels and green obsidian beads found in Izapa, Chiapas—evidence, as García-Des Lauriers contended, that elite goods were being imported, and not simply ceramics. She also highlighted the importance of shells gathered from coastal cities that were used in Teotihuacan murals and warrior trophies, as well as being abundant in the city’s famed apartment compounds.

While the presence of cacao in Teotihuacan is difficult to document archaeologically, there is abundant evidence that the bean was important to the city. García-Des Lauriers closed by discussing the exchange of incensarios between regions as evidence for the circulation of religious ideas and practices, a ritual economy that would have encouraged consumption of certain goods.

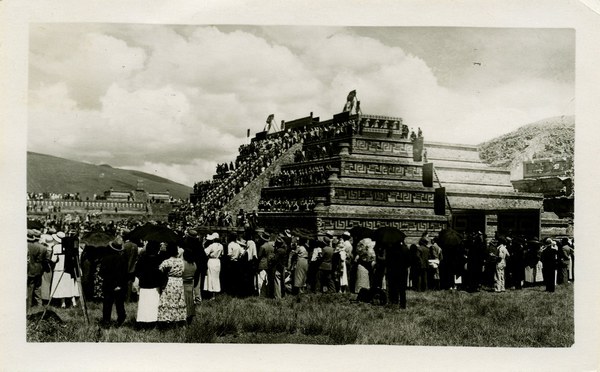

Barbara Arroyo of the Instituto de Antropología e Historia, Guatemala, delivered the final talk of the symposium, “Teotihuacan, Kaminaljuyu, and the Maya Highlands: New Perspectives on an Old Question.” Working with recent research and new composite data sets, Arroyo sought to update our understanding of the interactions between the two sites, which have been intensely studied since early excavations in the 1930s unearthed Central Mexican ceramics in mounds at Kaminaljuyu.

Kaminaljuyu’s important strategic position in the Maya Highlands, as Arroyo explained, meant it stood in the path of important trade networks; the site’s long history of occupation, from roughly 1000 BC to AD 900, meant its interactions with other societies were extensive. Structural similarities between Kaminaljuyu and Teotihuacan, like their agricultural canals, layouts, and architectural compounds, probably facilitated interactions: “the symbolic meaning of landscape was an important factor shared between these cities.” As Arroyo contended, these symbolic first steps might later have materialized into strong commercial connections.

After Arroyo’s talk, William Fash of Harvard University presented an insightful summary of the symposium’s key issues.