A series of Serbian churches in the western Balkans, all founded by members of the Nemanjić dynasty in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, exhibited an unusual form of monumental decoration. Narrative scenes and isolated figures painted on the walls of these buildings featured backgrounds covered with gold leaf and patterned in imitation of mosaic tesserae. Introduced at the church of the Virgin at the Studenica monastery in 1208/9, the practice of transforming murals into what may be described as gold “pseudo-mosaics” was subsequently adopted in the decoration of the church of the Ascension at the Mileševa monastery (shortly before 1227), the church of the Holy Trinity at the Sopoćani monastery (ca. 1265), the church of the Annunciation at the Gradac monastery (ca. 1280), and the church of Saint Stephen at the Banjska monastery (ca. 1317–1321). The gold that once adorned the wall paintings of these dynastic shrines, however, has for the most part disappeared. Instead of gleaming precious-metal surfaces, what one now sees is the exposed layer of typically yellow-ocher underpainting bearing faint vestiges of simulated tesserae.

The gold pseudo-mosaics of medieval Serbia are without parallels in the extant corpus of monumental painting from both the Byzantine East and the Latin West. The gilding of murals—an expensive and fragile form of decoration—on such a massive scale is unprecedented, as is the idea of patterning the applied gold leaf to mimic mosaic cubes. Both phenomena have been poorly understood and their larger art-historical import insufficiently recognized. One of the reasons for this neglect is the lack of technical studies. The aim of the present project was to remedy this lacuna. Building on the results of the recently conducted examination of the Sopoćani murals by Aleksa Jelikić and Dragan Stanojević (“O zlatu na sopoćanskim zidnim slikama,” Saopštenja. Republički zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture 49 [2017]: 57–74), the project set out to investigate the use of gold in all the Serbian churches with pseudo-mosaics. Research was carried out through a combination of in situ examination, sampling, and laboratory microanalyses. Several microanalytical techniques were applied, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDXS), Fourier transformation infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Raman spectroscopy, and light microscopy (LM). The immediate goal was to identify the composition of the materials used—namely, metal leaves, adhesives, pigments, and plaster—and to reconstruct the painters’ working methods.

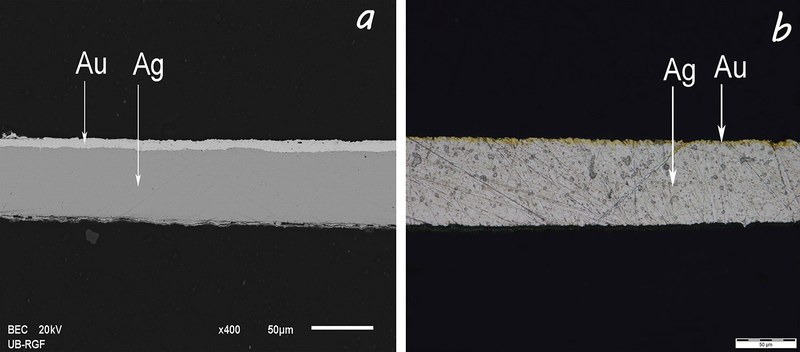

The results reveal a highly unusual, even experimental system of gilding. It is quite remarkable that in all but one instance, the painters employed leaves of what is known as “part gold”—a laminate produced by beating two sheets of gold and silver together. Introduced at Studenica, part gold continued to be employed throughout the thirteenth century; only at Banjska did the painters gild the murals with leaves of pure gold. Laminated gilding, to be sure, was commonly practiced in the Middle Ages, and for good reason. Metal leaves glued to images on the wall had to be considerably thicker than those used, for instance, in panel painting, which rarely exceeded 1 μm. A more substantial metal film was needed to counter the relative roughness of plaster, especially if the gilded areas were to be burnished, incised, or ornamented with punchwork. Laminated leaves, which could be over 50 μm thick, provided a convenient means to achieve this goal, while reducing cost, since they contained gold only in the surface layer. It bears emphasizing, however, that leaves of part gold were seldom used for the gilding of murals. Very few examples have been identified thus far, all of them coming from Germany, Austria, and Italy. Infinitely more common were leaves consisting of a tin foil overlaid with gold. Indeed, the gold-tin laminate was the material of choice in monumental painting. It seems that tin was preferred to silver not only because of its lower price, but also because this metal is less susceptible to the negative impact of humidity and other environmental factors. Writing around 1400, Cennino Cennini in his celebrated Il libro dell’arte warned against the use of part gold (oro di metà) because it “turns black straight away.” The instability of silver—its tendency to tarnish and corrode, especially when in contact with hydrogen sulfide from the atmosphere—is all too evident in the Serbian pseudo-mosaics. The characteristic dark smudges staining the now exposed backgrounds of these murals are residues of the corroded silver in the laminate. It is quite possible that the applied laminate began to deteriorate relatively early and that the awareness of its progressive decay prompted the decision to employ pure gold instead of part gold at Banjska.

Another notable feature of the Serbian pseudo-mosaics that came to light in the course of this research concerns the choice of the adhesives. Medieval artists employed a variety of substances to bind metal leaves to the wall. However, the combined evidence of modern technical studies, on the one hand, and medieval and early modern artistic treatises and recipe books, on the other, indicates that the most commonly used among these substances were oil-based mordants. The main component of such mordants was a drying, typically linseed, oil, often combined with varnish and/or siccatives such as lead white, minium, and verdigris. Interestingly, in the churches at Sopoćani and Banjska—the two monuments where it was possible to detect and analyze traces of the adhesive—the painters did not use oil-based mordants. Instead, they resorted to animal glue and another proteinaceous adhesive, most likely egg white or casein, respectively. In both instances, the painters’ choice of the gluing agent seems to have been dictated by the desire to produce a specific visual effect, namely, to render the gilded areas reflective and lustrous—comparable in appearance to real gold mosaics. Gold leaves laid over an oil-based mordant cannot be burnished and thus retain a matte or semi-matte finish. By contrast, proteinaceous adhesives make burnishing possible. In the case of laminated gilding, this kind of treatment is further facilitated thanks to the presence of another metal in the substrate which adds to the thickness of the leaves and thus makes them better suited to surface manipulation. It stands to reason, therefore, that the part gold once applied to the Sopoćani murals was given a shiny finish. The case of Banjska is slightly more complicated. Since the gilding in this church was not executed with laminated leaves, the painters had to contend with the relative roughness of the plaster, which, of course, made burnishing difficult. It appears that their solution was to modify the adhesive and use it, so to speak, as a cushion in order to create a smooth surface. The peculiar presence of calcium sulfate underneath the gold leaf in the samples collected at Banjska suggests that the painters probably reinforced the adhesive with a small amount of gypsum. Apart from preventing the expansion and contraction of the proteinaceous substance, the added gypsum is likely to have also been used to smooth out the surface of the underpainting in preparation for burnishing.

It should be clear from this brief report that the Serbian pseudo-mosaics were highly unusual, innovative, and technologically challenging works of monumental art. Their fabrication required not only considerable financial outlay, but also a great deal of skill and ingenuity. Far from being mere imitations or lesser substitutes for real gold mosaics, these works were products of a bold artistic vision. It is to be hoped that the present project will stimulate further inquiries into the nature of this vision. Future research would also do well to probe the broader significance of the Serbian pseudo-mosaics beyond their immediate cultural and geographical context. Indeed, these idiosyncratic creations offer a uniquely rich and rewarding case to investigate a number of issues, among them the relationship between painting and mosaic; the medieval notions of mimesis, medium, and remediation; and not least, the interplay among economy, technology, and aesthetics in the practice of gilding.