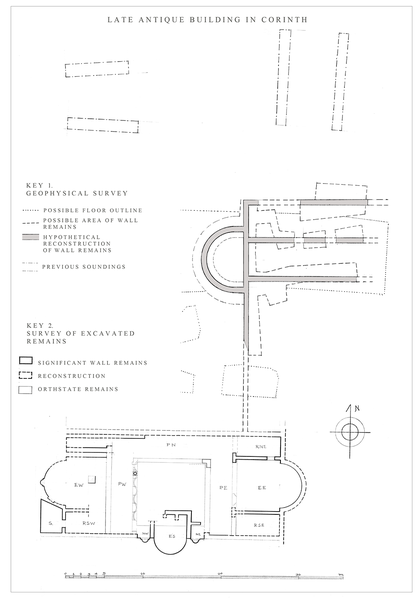

In the south part of the archaeological site of ancient Corinth, ascending from the forum up the slopes of the Acrocorinth, the visitor encounters the remains of an impressive ancient building, consisting of three apsidal structures around a peristyle court. This structure was brought to light by rescue excavations conducted in the 1950s by Demetrios Pallas, then Ephor of Antiquities for Western Greece, to whose efforts we owe the preservation of the remains. The excavation, however, was never published, and thus one of the arguably most impressive buildings of the Late Roman and early Byzantine periods visible in Corinth has never received a proper study.

Covering an area of ca. 350 square meters, the excavated remains have a sophisticated architectural layout, combining a nymphaeum with three apses, two apsidal halls, and a peristyle surrounding a shallow pool. The building displays typical elements of Roman and late antique residential architecture, known from several third- and fourth-century houses in Greece and the southern Balkans. It is likely to have remained in use with repairs into the sixth century and, after its abandonment, two vaulted tombs decorated with Christian wall paintings and inscriptions were constructed in the west apsidal room, very probably dating from the late sixth or seventh centuries.

In collaboration with Dr. Nikolaos Karydis (University of Kent), Dr. Demetrios Athanasoulis (former head of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Corinth), and Ms. Panayiota Kasimi (current head of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Corinth), I have undertaken a study of this building, based on a thorough revisiting and recording of the architectural remains in situ, an investigation of the excavation records, and new finds uncovered during clearing works carried out by the Ephorate in 2013.

In order to acquire a better understanding of the context of the whole complex, a small-scale geophysical survey on the adjacent plots to the north of the excavated remains was conducted in October 2019, in collaboration with archaeology technicians Lloyd Bosworth and Frederick Birkbeck of the Department of Classical and Archaeological Studies of the University of Kent. This survey campaign was possible thanks to the project grant generously awarded by Dumbarton Oaks, for which I extend my thanks to the director, the program director, and the Byzantine senior fellows.

Objectives and Method

This report presents the results from magnetic and earth resistance geophysical surveys, which were conducted on the site described above.

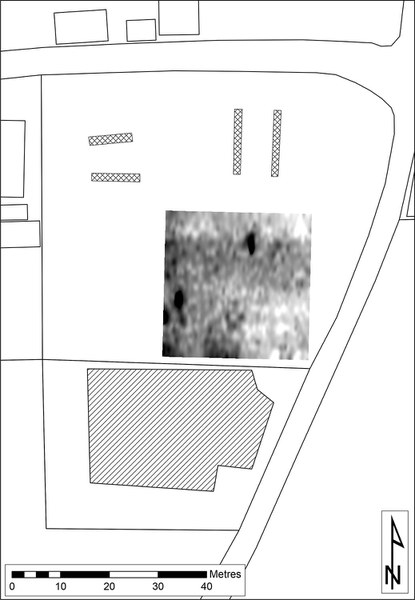

The excavated building is located within the modern settlement of ancient Corinth and borders on a road to the east, on residential properties to the south and west, and on two undeveloped, privately owned plots of land to the north (fig. 1). Our survey used noninvasive geophysical methods to establish the extent of any buried remains in the two undeveloped plots and draw up a plan of any discoveries made.

The magnetic survey was carried out using a Bartington Grad601‐2 dual fluxgate gradiometer. Sensor separation is fixed at 1.0 m and the geomagnetic field gradient is measured in nanoTesla (nT).

The earth resistance survey was carried out using a Geoscan RM85, using a parallel twin probe array with a probe separation of 0.5 m. A zigzag survey pattern was employed, and data was automatically logged in 30 m grid units to the machine’s internal memory. Data were collected at a sample interval of 0.25 m and a traverse interval of 1.0 m.

One 30 m × 30 m survey grid was aligned to the southern boundary line, which also proved to be perpendicular to the slight slope direction of the field, and thus it was possible to minimize deviation in traverse pacing that would result from walking up and down the slope.

Data processing was carried out using TerraSurveyor 3.0.34.10 to produce grayscale plots on a continuous gradient from black to white.

Graphics showing the interpretation of the grayscale plots were produced using ESRI’s ArcMap 10.5.1, Adobe Illustrator CS6 and Adobe Photoshop CS6. All maps were produced using ArcMap 10.5.1 GIS package.

Geophysical Survey Results

The surveyed area was 30 meters square, immediately north and northeast of the excavated remains.

The conditions of the soil were unfavorable for both magnetometry and resistivity. With resistivity being reliant on ground moisture to conduct the electrical charge, the very dry soil conditions, exacerbated by the rocky nature of the topsoil matrix, created a very challenging survey. The expected buried archaeology of walls and foundations would not typically be detectable through magnetometry, as these feature types rarely show magnetic responses sufficiently different from the natural background geology.

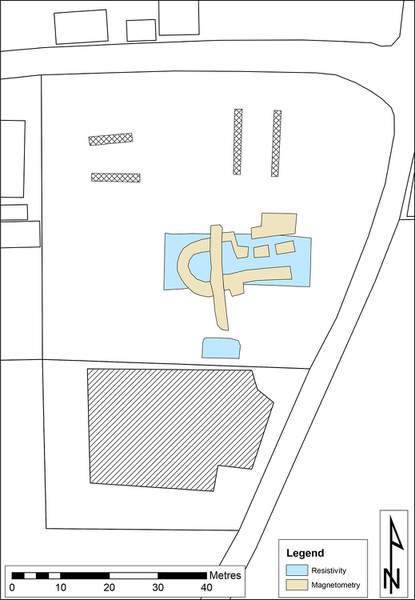

Despite these obstacles, the results from both techniques have shown the presence of buried features, although with less clarity and definition than would be hoped for under better conditions (figs. 2–3).

Taking the resistivity results first (fig. 2), a broad band of high resistance running east west across the surveyed grid square is consistent with what would be expected for a compacted surface (colored blue in fig. 4). Such a surface suggests the presence of a floor or trackway, whether deliberately laid or created by other forces. The relative phasing of this surface is not present in the results.

A sub‐rectangular high resistance anomaly to the south of the plot, and likely continuing beyond the survey grid, may be similar to the previously discussed feature. The alignment of this feature corresponds well with the visible excavated remains and may in fact be associated with them.

Turning to the magnetometry (fig. 3), there are clear features with the characteristics of walls delineating rooms (colored tan in fig. 4). This is a somewhat surprising result from this technique as it is the least favored to detect such features. An apsidal room and possible doorways are all discernible in the results, as well as perhaps evidence of phasing with the presence of a cross‐cutting linear feature running north-south. Evidence for this feature being earlier or later is not present in the results.

The overall alignment of this building is consistent with that of the visible excavated remains to the south of the site suggesting that they could be contemporary structures (fig. 5).

Conclusions

The image resulting from the survey indicates the presence of an apsidal structure of a size comparable to the two apsidal halls of the neighboring excavated building (fig. 5). It seems to have the same east-west axis as the excavated one, with its apse oriented westward. The structure is likely to represent the continuation of the excavated building complex or perhaps a separate one with similar architectural features. The position of the apse suggests that the symmetrical plan which characterizes the excavated building does not continue further north. Yet, if the structures located by our survey belong to the same complex, it follows that this was a building of substantial size, perhaps with several units of reception rooms around open courts. These remarks can only be verified through excavation in the future.