In 2011, the 23rd Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities (Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports) conducted a rescue excavation at the close perimeter of the church of Hagios Sozon for the purposes of a drainage project and the restoration of the church. The excavation, although of a limited extent, brought to light the foundation of the church, numerous burials, and important artifacts. Thanks to the generous support of the Dumbarton Oaks Project Grant, we implemented a multidisciplinary approach to the analysis of Byzantine architecture, material culture, funerary context, and skeletal evidence unearthed at this significant monument. The analysis of the foundation and artifacts was conducted by Giannis Vaxevanis (University of Athens); Kalliopi Mitsopoulou (Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia) made the illustrations. Osteological analysis was conducted by Paraskevi Tritsaroli and was accommodated at the Malcolm H. Wiener Laboratory for Archaeological Science, ASCSA. Stable isotope analysis for paleodietary reconstruction was processed by Estelle Herrscher (CNRS, France). A bioarchaeological project summary and the skeletal dataset will soon be available at https://openconext.org/.

The Church and the Burial Ground

The church of Hagios Sozon is in Orchomenos, close to the well-known ninth-century church of Panagia Skripou. Hagios Sozon is a small triconch church (fig. 1), founded during the twelfth century.

It is notable for its architectural features, such as the twelve-sided dome and the lower part of the walls made of large spolia. In the interior of the church are preserved wall paintings dated to the end of the twelfth century and the second half of the sixteenth century, the latter attributed to the brothers Georgios and Frangos Kontaris, renowned painters from Thebes.The foundation of the monument was revealed and examined all around its perimeter within a depth of 1.05 m. This is a particularly solid construction that incorporates large spolia forming a solid base on which lay the three niches of the church in order to avoid sinking into the soft bedrock. In addition, eight walls belonging to a building which preceded the church were also found, as they were incorporated into its foundation. Within the same depth and in the close perimeter of the church, three cist graves, individual primary burials in six stone- or tile-lined pits, eleven burials in shallow pits, seven deposits of human bones, and numerous commingled and scattered skeletal remains were found and analyzed. With the exception of the cists, most burials were performed directly on the ground or even on the upper horizontal surfaces of earlier walls. The primary burials were oriented west–east and the deceased laid in a supine position, in some cases with upper limbs folded on the chest or abdomen. The few burial offerings range from the middle- to the post-Byzantine period and testify to the diachronic funerary use of the church since its foundation. Burials were poorly constructed and furnished, likely suggesting an agrarian community in the Boeotian countryside.

Material Culture and Burial Offerings

The analysis also focused on more than 200 artifacts dated to the Byzantine and post-Byzantine period (12th–19th century): (1) numerous pottery fragments and other clay objects—fragments of a tobacco pipe, tiles, etc., (2) bronze and silver jewelry—one buckle and three rings, two of which are currently part of exhibition of the Museum of Thebes, (3) two spherical metal buttons, (4) six iron shoe protectors, (5) several iron nails and other minor objects, (6) thirteen coins, and (7) four marble sculptures.

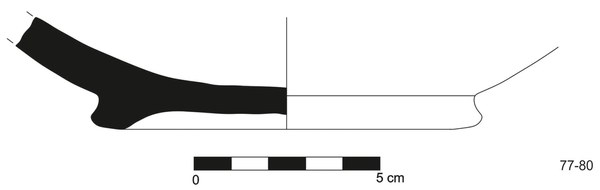

The middle Byzantine and early modern pottery is fragmentary; the majority of the artifacts are glazed tableware, but unglazed wares, including cooking, serving, storage, and transport vessels, were also identified. The earliest cases of glazed pottery belong to the well-known and widely diffused types of the period of the foundation of the church (slip-painted ware, green and brown painted ware, fine sgraffito ware, and incised sgraffito ware; fig. 2a, 2b).

Late Byzantine pottery is also well represented, suggesting the use of the church during a period when Boeotia was under Western rulers (Franks, Catalans, Navarrans, Florentines). Part of the pottery also belongs to well-known types of post-Byzantine and modern times (15th–19th century), when Boeotia was part of the Ottoman Empire; the combined examination of the pottery and burial offerings of that period suggest the funerary use of the church in accordance with Christian customs. Finally, the pottery assemblage offers a complete picture of the range of ceramics used in each period, thus being comparable to ceramic finds from other Boeotian sites such as Thebes, Thisbe, and Akraiphnio.

Of particular interest is a fragment of a double-sided panel found during the excavation (fig. 3) that originates from the now-destroyed marble screen of the church of Panagia Skripou (873/4); the screen is attributed to the so-called “Theban workshop” and it is known thanks to the reconstruction proposed by Α. Η. S. Megaw.

During the restoration of the monument, two more fragments of double-sided panels from the same screen were found embedded in the walls of the church; finally, a fragment of a cornice that was found during the excavation also comes from the church of Skripou. As such, the evidence recorded from Hagios Sozon is of great value, since it suggests that the dispersal and secondary use of various sculptures of the church of Skripou took place long after its foundation in 873/4.

Burials and Human Skeletal Remains

Eleven primary burials belonged to subadults, including young children and one preterm infant, while seven were performed for adults. A collective burial was found in cist grave I and included two primary inhumations and numerous redeposited remains of eight individuals. Cist grave II held the primary burial of a six-month-old infant (fig. 4).

Cist grave III contained the remains of three individuals, of which two were adults and one was an infant. On top of this grave, the reassembled bones of a young individual were covered with a bronze buckle. Commingled remains were found in the whole burial space, and they represent the major part of the human osteological assemblage.

The sample includes more than fifty individuals. All ages are represented, but preterms and perinatals are the most numerous; these individuals also share a common paleopathological profile, including frequent cases of skeletal and dental pathological markers of deprivation and nonspecific infection. This evidence suggests that environmentally related and impoverished living conditions contributed to their premature death. Biochemical analysis on human and animal bone samples will further elucidate correlations between inadequate diet and health to shed more light on the lives and deaths of these people.

Bibliography

Armstrong, P. “Byzantine Thebes: Excavations on the Kadmeia, 1980.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 88 (1993): 295–335.

Bouras, Ch., and L. Bouras. Ἡ ἑλλαδικὴ ναοδομία κατὰ τὸν 12ο αἰώνα. Athens, 2002.

Koilakou, Ch. “1η Εφορεία Βυζαντινών Αρχαιοτήτων.” Αρχαιολογικόν Δελτίον 54, B1 (1999): 118–36.

Koilakou, Ch. “Επισήμανση τοιχογραφιών του εργαστηρίου των θηβαίων ζωγράφων Γεωργίου και Φράγκου Κονταρή στην περιοχή της γενέτειράς τους.” Δελτίον της Χηριστιανικής Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας 22 (2001): 191–208.

Megaw, A. H. S. “The Scripou Screen.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 61 (1966): 1–32.

Pallis, G. “Η διάδοση της τεχνοτροπίας των γλυπτών του λεγόμενου ‘θηβαϊκού εργαστηρίου’ (β΄ μισό 9ου αι.). Μερικές παρατηρήσεις.” In 4ο Αρχαιολογικό Έργο Θεσσαλίας και Στερεάς Ελλάδας, Πρακτικά επιστημονικής συνάντησης, Βόλος, 15.3–18.3.2012. Vol. 2, Στερεά Ελλάδα, ed. Α. M. Ainian, 803–10. Volos, 2015.

Papalexandrou, A. “The Church of the Virgin of Skripou: Architecture, Sculpture and Inscriptions in Ninth-Century Byzantium.” PhD diss., University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, 2000.

Vionis, A. K. “The Byzantine to Early Modern Pottery from Thespiai.” In Boeotia Project, Volume II: The City of Thespiai. Survey at a Complex Urban Site, ed. J. Bintliff, E. Farinetti, B. Slapšak, and A. Snodgrass, 351–74. Oxford, 2017.

Vroom, J. After Antiquity: Ceramics and Society in the Aegean from the 7th to the 20th Century A.C.: A Case Study from Boeotia, Central Greece. Leiden, 2003.

Vroom, J. “Byzantine Garbage and Ottoman Waste.” In Thèbes: Fouilles de la Cadmée, II.2, Les tablettes en linéaire B de la Odos Pelopidou, le context archéologique. La céramique de la Odos Pelopidou et la chronologie du linéaire B, ed. E. Andrikou, V. L. Aravantinos, L. Godart, A. Sacconi, and J. Vroom, 181–233. Pisa, 2006.