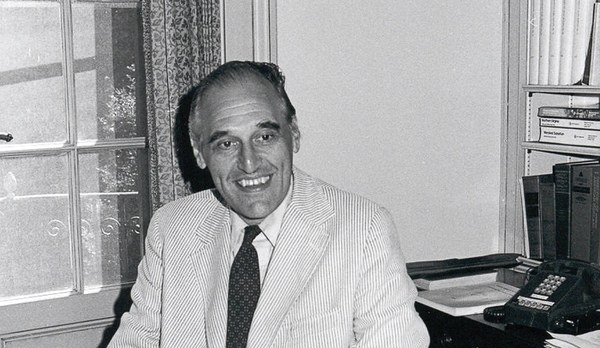

Giles Constable was the third director of Dumbarton Oaks and the first to be chosen from the ranks of Harvard University medievalist professors, a tradition that remains unbroken to the present day. As director, he quickly realized that changes were needed at Dumbarton Oaks in order to strengthen the institution, both physically and intellectually. Constable articulated these changes in his annual reports to the President of Harvard University, arguing that Dumbarton Oaks needed to evolve from the tradition of “perceived elitism” and the “Founders’ paternalism” to a new era of “academic institutionalization.” By 1984, at the end of his seven-year tenure, most if not all of the changes he envisioned had been made.

Physical Plant

- The roofs of all areas except the Orangery and the Pre-Columbian Pavilion were replaced.

- The third floor of the Main House was reinforced with steel and concrete in order to install shelving for part of the library’s holdings.

- Library shelving, including compact stack shelving, was installed in areas of the basement to serve the growing libraries of the three studies programs.

- Basement areas were retrofitted to house the Princeton Index, the Census of Byzantine Art in North American Collections, and archival holdings.

- Areas housing books and photographs were maintained at a constant temperature and relative humidity level for the first time.

- Other areas at Dumbarton Oaks were air-conditioned for the first time, which allowed for a twelve-month use of the physical plant.

- The Fellows Building (now known as the Guest House) was renovated with a new kitchen and dining room and en-suite bathrooms in each bedroom (see post).

- Down and spot lights were installed in the Music Room.

- Plans were initiated for the creation of the Byzantine Courtyard Gallery and excavation under the Music Room. This would come to fruition during the next administration.

Academic Programs

- Appointments of Dumbarton Oaks professors in Byzantine fields at Harvard University were inaugurated. Angeliki Laiou was appointed Dumbarton Oaks Professor of Byzantine History and Ihor Ševčenko was appointed Dumbarton Oaks Professor of Byzantine History and Literature, beginning in 1980–81.

- Senior research associates and research associates were appointed at Dumbarton Oaks in lieu of having a permanent faculty. These appointments, however, were allowed to lapse beginning in 1984.

- Joint academic appointments allowing some research associates to teach at universities were created. The associate spent half the academic year at Dumbarton Oaks pursuing research and half the year teaching as an assistant professor.

- The senior fellows took on the responsibility of selecting annual fellows and began to interview applicants at Dumbarton Oaks.

- The fellowship program was increased from twenty-five appointments in 1977–78 to fifty-seven appointments in 1983–84. This was in part due to the inauguration of the summer fellows program in 1980–81, when twelve summer fellows were appointed for the first time.

- An “Author Index of Byzantine Scholarly Literature II” was created in 1977–78, based on the annual bibliographies published in the Byzantinische Zeitschrift; this author index was published in microfiche format, and from it several “Dumbarton Oaks Bibliographies” were created on various subjects;

- The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium was initiated by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and was under the direction of Alexander P. Kazhdan.

- The Pre-Columbian library was catalogued under a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Institutional Policies

- The gardens were opened to visitors in the summer, beginning in 1978. An admission fee to the gardens was charged in order to increase revenue, beginning in 1982–83;

- The collections were opened to the public in the summer, beginning in 1979.

- A docent program was inaugurated for the collections, beginning in 1982–83.

- Judy Ullmann Siggins was appointed as assistant director in 1978.

- Computers were introduced into the workflow at Dumbarton Oaks in 1983–84. They were employed by the Byzantine library to process acquisitions and serials, by the director’s office for document word processing, and for printing Greek in the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium.

The changes instigated at Dumbarton Oaks during Giles Constable’s administration were formidable and set a new trajectory for the institution. Nevertheless, Constable also faced several difficult and controversial challenges. In 1970, Constable had been one of the ten members that authored the “Report of the Committee on the Future of the Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies.” That report, which was submitted to Harvard President Nathan M. Pusey, had strongly recommended the continuation of the position of Director of Byzantine Studies and the retention of the permanent faculty at Dumbarton Oaks. However, as director, Constable decided to gradually disband the permanent faculty. He felt that, having no students, they were both an unnecessary and an expensive component of the institution. In their stead, he appointed research associates in the Byzantine Studies program, often trying to find them joint appointments at universities. The senior fellows, however, would let this position lapse beginning in 1984.

In January 1977, William Loerke resigned as director of Byzantine Studies, a position he had held since 1969. John Meyendorff was appointed acting director of studies for the 1977–78 academic year, after which Constable decided to let the position lapse and appointed Alice-Mary Talbot associate for academic affairs, a position she would hold for two years. The position of director of Byzantine Studies would remain unfilled until 1991.

Early in his tenure, Constable was also plagued with the rumors of the removal of the scholarly apparatus of Dumbarton Oaks to Harvard University. As he reported to the president of Harvard University: “I spent a great deal of time discussing the future of Dumbarton Oaks, and especially allaying fears that any improper steps were planned. The attitude of suspicion, not to say hostility, that was apparent at first began to change in the course of the year and I am confident that a period of scholarly cooperation and vitality lies ahead.” This unfounded but common perception that the research programs and their libraries would be moved to Harvard University was the principal reason for Constable’s 1978 address, “Dumbarton Oaks and the Future of Byzantine Studies,” at that year’s Byzantine Studies Conference.

Also during Constable’s tenure at Dumbarton Oaks, a period of double-digit inflation began to decimate the institution’s endowment. Both the Office of the Budget at Harvard University and a report undertaken by Mary Proctor in 1977 feared that expenses might exceed income. The recommendations were to cut back on expenses, to reduce activities at Dumbarton Oaks, and to look for outside sources of income. In light of the double-digit inflation of the period, the Trustees for Harvard University decided to impose a limit on the Dumbarton Oaks budget for publications; to restrict fieldwork, in all but exceptional cases, to the completion of current projects; and to eliminate the appropriations for acquisitions for the museum collections (though objects could still be acquired through the sale or exchange of items not related to the research or display collections, an option that was occasionally exercised). Through belt-tightening and increased revenue through grants, entrance fees, and contributions, Giles Constable guided Dumbarton Oaks back to a course of financial stability.