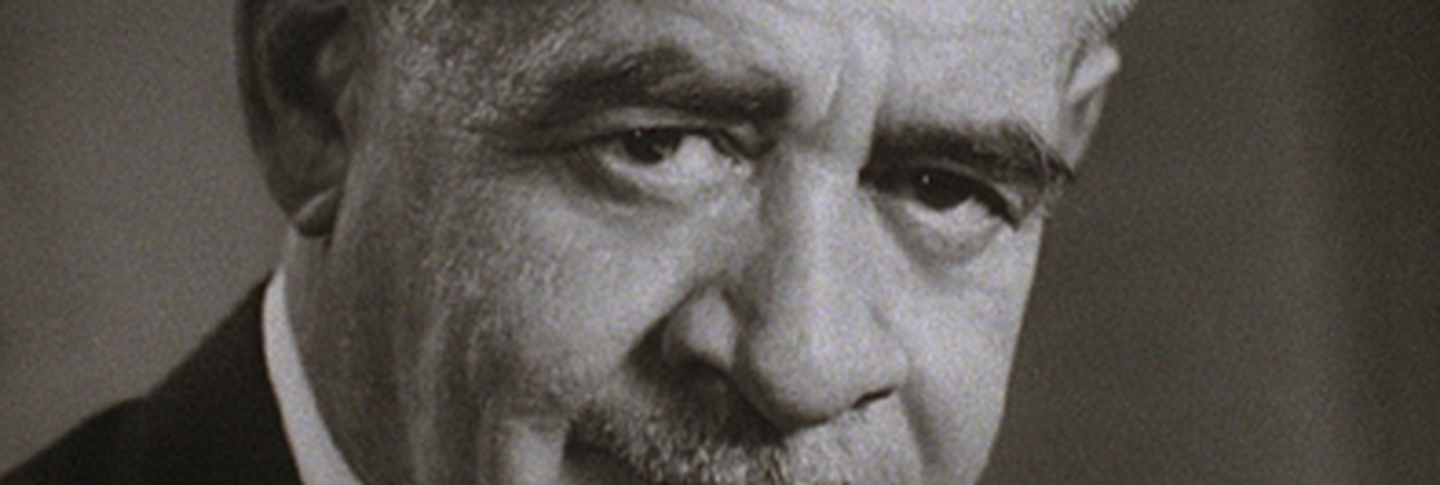

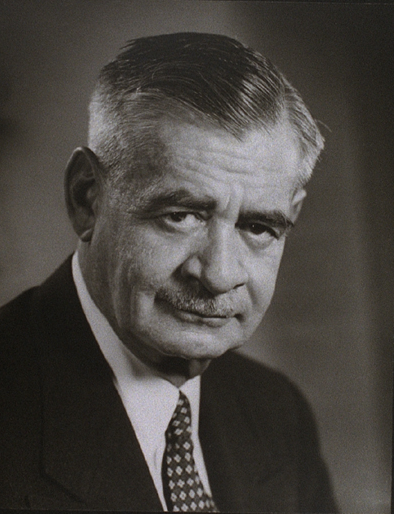

From 1946 on, the Pre-Columbian archaeologist and scholar Samuel Kirkland Lothrop (1892–1965) was intimately associated with the Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art and the Dumbarton Oaks program in Pre-Columbian Studies. In 1946, when Bliss began planning to lend his collection to the National Gallery of Art, he wanted the exhibition to have a handbook. He first turned to his friend, Alfred Tozzer, at the time a member of the Department of Anthropology at Harvard. Tozzer recommended his former student, Sam Lothrop. Lothrop, a researcher at Harvard’s Peabody Museum, went to work on the collection. He was instrumental in preparing Indigenous Art of the Americas: Collection of Robert Woods Bliss, published in 1947, the year the exhibition opened to the public at the National Gallery. Impressed with Lothrop’s work, Bliss relied on him as a principal adviser on the acquisition of Pre-Columbian objects and the formation of his collection. Bliss also turned to Lothrop to author much of the text of a more luxurious book on the collection that was published in 1957, entitled Robert Woods Bliss Collection, Pre-Columbian Art. This book was the first “coffee-table” book on the topic and featured full-page color photographs of isolated objects by the well-known photographer Nikolas Muray (1892–1965).

Lothrop was educated at the Groton School, where he played football and rowed crew. According to his younger brother Francis, Lothrop’s friendship with William Crocker (a Groton classmate) fostered his interest in archaeology, as he found himself particularly drawn to the objects in the antiquities collection of Crocker’s father. After Lothrop’s matriculation at Harvard in 1911, his archaeological interests were reinforced by Alfred Tozzer, who encouraged him to get his first taste of fieldwork in Pecos, New Mexico, under the direction of Alfred V. Kidder. Lothrop graduated in 1915, and for two years traveled throughout Central America as a research associate of the Peabody Museum. He studied Pre-Columbian collections in Mexico, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic, and excavated at various sites, including Maya Tulum, under the direction of archaeologist Sylvanus Griswold “Vay” Morley.

Unbeknownst to Lothrop, Morley was also a secret agent, and had been charged with investigating rumors of German submarine bases in southern Mexico and in Central America. While excavating in Honduras in 1917, Lothrop received a telegram from Tozzer, saying: “Meet Morley Guatemala City May 3rd without fail.” At that meeting, Morley convinced Lothrop to become an agent, and he entered the remainder of the First World War as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Military Intelligence Corps.

After the war, Lothrop returned to his graduate work in archaeology and anthropology at Harvard, earning his doctorate in 1921. From 1924 until 1930, Lothrop was a member of the research staff at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York. When funding for that position was cut because of the Great Depression, Lothrop returned to Harvard as a research associate and curator of Andean Archaeology at the Peabody Museum, a position he held until he retired in 1958.

Lothrop believed that archaeology should be accessible, and took pains to ensure that broad audiences could understand his writing. He limited his use of jargon and strove to build a narrative account in his publications, placing his subjects in their geographical, historical, artistic, and technological contexts. Lothrop also once employed this “popular touch” to rein in a group of plunderers. Convincing them to form an archaeological “society,” Lothrop helped them obtain their “loot” while still preserving the invaluable stratigraphic information that had previously been lost in the course of their illicit digging.

Lothrop’s long association with Robert eventually resulted in a deep friendship. He initially maintained a formal relationship with Bliss, who endeavored to initiate a greater informality with his collaborator. It was not until January 1951, after nearly five years of acquaintance, that Lothrop finally signed a letter “Sam.” Bliss remarked in his next letter: “I am glad you signed your letter ‘Sam,’ and the next one to me I hope you will begin ‘dear Bob or Robert.’ I think the Mr. we might consider thrown into the excavation refuse.” Similarly, one day at the National Gallery, Lothrop held up a piece of jade and turned to Bliss and remarked: “The color of the jade changes with heat.” Without missing a beat, Bliss replied: “I’d better not give that to my girl friend.” On the death of Robert Bliss in 1962, Lothrop published a memoir in which he remembered that:

Robert Woods Bliss not only assembled a unique American collection, but he also helped to direct, or himself sponsored, a large amount of field research. To those who knew him, he will be remembered for his multiple interests, his unfailing courtesy and kindness, and his gift for friendship.

Lothrop was well respected. Dudley T. Easby Jr. wrote that he was a “kind, decent, generous, and thoughtful man,” and noted: “The countless times he gave of himself to help others will never all be known.” His friend Gordon R. Willey summed him up as “a gentleman, a scholar, and an absolutely first-rate archaeologist.”