I constructed a website to document and interpret East End Cemetery, a historic African American burial ground that straddles the border between Henrico County and the city of Richmond, Virginia. By the last decades of the 20th century, English ivy, Chinese sumac, and greenbrier had swallowed this once well-tended memorial park along with its neighbor, Evergreen.

Both cemeteries were founded in the 1890s by prominent black Americans, who seized opportunities made possible by the Union victory in the Civil War and the brief period of Reconstruction that followed. They built their own churches, businesses, mutual aid societies, and schools in the face of increasing white opposition to black citizenship and social equality, which solidified into Jim Crow law.

Not only did segregation, one of the defining features of Jim Crow, regulate the lives of black Americans, it followed them to the grave. Barred from white cemeteries, black Richmonders created their own. At East End alone, there are an estimated 17,500 interments—estimated because no records have been found. Among those buried there are members of what historian Robert F. Engs calls “Freedom’s First Generation,” black people born in the era of chattel slavery who lived to experience life after emancipation. Their children and grandchildren were also laid to rest at East End. They were doctors, lawyers, tobacco workers, domestics, letter carriers, teachers, ministers.

Since 2013, there has been a sustained volunteer reclamation effort at East End. We have cleared roughly six acres of the 16-acre cemetery and recovered nearly 3,000 grave markers. Our mission has two tracks: the first is the physical reclamation of the cemetery from nature and neglect. The second is the historical reclamation of a community ignored or misrepresented in the dominant Jim Crow-era narrative.

With website builder Jolene Smith and designer/content creator Erin Hollaway Palmer, I finished a beta version of eastendcemeteryrva.com, and have since populated it with additional images (contemporary and archival), data, and documents. As a photographer and journalist, one of my primary concerns was to create a visually dynamic site, featuring photos I have taken as well as archival images from relatives of people interred at East End and from public-domain sources. We also wanted a site rich in factual information and primary documents about the cemetery and the community it served, which can expand as visitors begin to contribute material digitally. The design and architecture of this platform give us the ability to showcase material we create and find as well as user-generated content.

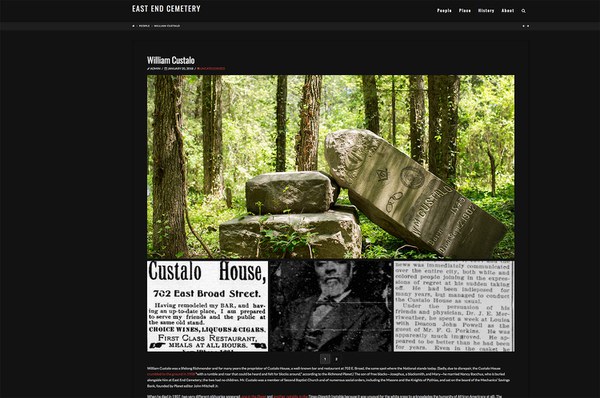

The site has three main sections: “People,” “Place,” and “History.” The “People” section, which is searchable by several means, provides immediate access to photos and data related to particular individuals buried in the cemetery. Included among these photos are my images of headstones, archival images, and scans of primary documents—newspaper ads and articles, interview transcripts, letters, pages from antebellum Registers of Free Negroes.

I have taken between 200 and 300 photos of grave markers in the past year. The process of uploading them to the website continues. There are many more headstones to photograph—volunteers have unearthed roughly 3,000. I will continue to be the principal photographer, but going forward we will accept photos from the public that meet our standards. To add richness and historical depth to the site, we are reaching out to families and asking for scans of archival photos depicting their relatives who are interred at the cemetery.

We continue to write deeply researched short biographies of certain individuals—generally speaking, those for whom records exist. We plan to solicit written contributions, primarily from family members, through the website as well. As with images and documents, we are able to vet and edit such submissions to ensure they mesh with our content.

“Place” features a gallery of contemporary photos. At the moment, the majority of the images are mine—I have been photographing the landscape of the cemetery and its neighbor, Evergreen, since mid-2014—but we will be taking submissions from (skilled) photographers.

The backbone of “History” is a timeline with major events that involved or affected the black community in Richmond. Entries cover the time span during which the people interred at East End—and a generation before and after them—lived. That period begins in the 1840s and extends into the Civil Rights era. (There were burials at East End as late as 2002, but the vast majority of burials were before the 1980s.) We will expand the “History” section by adding essays about critical events relevant to the black community during that time.

In 2016, the University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab began a website that grew out of a proposed collaboration with me and the Friends of East End, the 501(c)(3) restoring the cemetery. As we developed eastendcemeteryrva.com, we communicated and cooperated with the builders of the UR site. It was agreed that our site would focus on visuals (photos, documents, video) as well as narratives (short biographies, essays, and eventually audio oral histories); UR would concentrate on mapping the cemetery and creating an interactive geospatial tool to allow users to locate individuals buried at East End and learn basic data about them. Undergraduates have been plotting GPS coordinates for markers. (More experienced GPS plotters are overseeing that work and refining the data being generated.)

There will be some limited content overlap. Several UR students have written short biographies, which Erin has vetted and edited. These bios will be posted on our website. We have embedded links to the UR site on eastendcemeteryrva.com; UR is embedding our link on its site. We are committed to the two-track restoration of East End, and we hope this website becomes integral to that process.