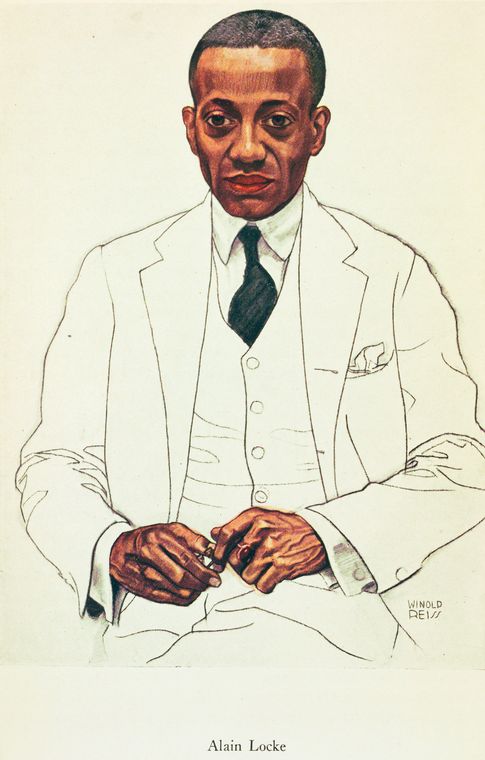

Alain Locke Collection of African Art

Alain L. Locke was known as the “Dean of the Harlem Renaissance,” and in his collecting, criticism, and support for the art community, he argued for the aesthetic value of African art and exhorted African American artists to draw inspiration from it.

Locke defined the possibilities and parameters of African American art and gave it a past as well as a future.

Mary Ann Calo

The Howard University Gallery of Art holds the African art collection of Alain Leroy Locke (1885–1954), one of the most important intellectuals of the twentieth century. A cultural theorist, art critic, and collector, Locke served as chair of Howard University’s Department of Philosophy from 1921 to 1953. Following Locke’s death in 1954, 365 pieces from his collection of African art were bequeathed to Howard University.

Early Life

Alain Leroy Locke was born on September 3, 1885, to Pliny and Mary Hawkins Locke. He spent his childhood in Philadelphia, a center of abolitionist activity during the Civil War. Despite this legacy, Philadelphia was still a segregated city while Locke was growing up; as a young black man, he experienced firsthand the extreme racial injustice that would shape his academic and personal interests. After his father died in 1891, Locke’s mother became the central figure in his life.Leonard Harris and Charles Molesworth, Alain L. Locke: The Biography of a Philosopher (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008), 14. A teacher, Mary Hawkins Locke sought to develop her son’s intellectual and cultural curiosity.

Locke began classes at Philadelphia’s prestigious and academically rigorous Central High School at the age of thirteen, where his classmates were on average fifteen, earning full “Excellent” marks except for a single “Good” mark in drawing. After graduating from high school in 1902, Locke enrolled in Central High School’s School of Pedagogy and Practice. There, he developed a passion for teaching that would motivate him to pursue a career as a professor and community leader.

Harvard and Beyond

After attaining his AB, Locke was accepted to Harvard University, where he studied philosophy and literature. Outside of his academic pursuits, Locke developed a highly individualistic and elitist perspective to match his intellectual successes. Influenced by the Harvard community’s focus on moral perfectionism, rationalism, and Anglophilia, Locke rejected the “coarse” entertainment and ungentlemanly culture of lower-class black students.Harris and Molesworth, Alain L. Locke, 32. This tension between his own academically elite identity and his desire for a unified racial identity would often resurface in his later writings.

Locke left Harvard in 1907. Although he was not the first African American to graduate from Harvard—that honor belongs to Richard GreenerAn earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that W. E. B. Du Bois was the first African American graduate of Harvard (updated September 7, 2021).—he was the first to receive the prestigious Rhodes Scholarship for study at Oxford.Harris and Molesworth, Alain L. Locke, 28. Locke continued to pursue his interest in philosophy, first writing a thesis at Oxford and then enrolling at the University of Berlin for a year of further study. In the fall of 1911, Locke returned to the United States to travel the American South with Booker T. Washington (1856–1915), where he learned a great deal about African American education in the region.

A Growing Interest

Locke’s interest in African art and culture blossomed during his time at Oxford. He helped create the African Union Club and the Cosmopolitan Club, both of which were intended to foster cross-national friendships and understanding. Locke was particularly intrigued by the connection between African and African American culture, an interest that persisted throughout his scholarly life and influenced the development of his art collection. Importantly, Locke sought to foster the recognition—both within the art world and the broader public—of the artistic excellence of African and African American artists, a recognition that had been impeded by racism.

Locke’s interest in African art and artifacts gained momentum in the 1920s, when he began to devote a considerable amount of personal time and resources to developing his collection. This acceleration in collecting was prompted by his growing belief in the connectedness of different cultures and the ability of artistic expression to evoke those connections. He articulates as much in his essay “Impressions of Luxor,” written after the opening of the tomb of King Tutankhamun in 1922, which Locke had seen firsthand during his 1924 sabbatical to Sudan and Egypt. He remarked:

Great cultures are the result invariably of the fusion of several cultures, the impetus given to one culture by contact with others,—fermenting of one civilization by another. Once we recognize this principle of the cross-fertilization of cultures, we shall be over our greatest difficulty in the broad comparative study of civilization, and our science of man will have been clarified of its greatest pollution, ethnic bias in terms of cultural prejudice.Alain Locke, “Impressions of Luxor,” Howard Alumnus 11 (1924): 74–78; reprinted in The Works of Alain Locke, ed. Charles Molesworth (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 179.

Locke’s involvement in the arts, however, stretched far beyond the act of collecting. He was an avid advocate for the arts, championing the work of and helping secure funding for poets, writers, and visual artists. He frequently contributed essays to exhibition catalogs and, in 1927, he organized the landmark exhibition of works from the Blondiau-Theatre Arts collection.Harris and Molesworth, Alain L. Locke, 224. Though it never came to fruition, Locke was also heavily involved in the planning of a proposed Harlem Museum of African Art.Harris and Molesworth, Alain L. Locke, 245. Despite his lack of formal education in art history, Locke frequently wrote academic essays about issues of interest within art history, persisting even when his contributions were criticized by his colleagues at Howard University.

Howard University

In 1925, Locke was fired from Howard University. Though he had shown himself to be a scholar of remarkable ability and productivity, Locke was frequently at odds with the university’s president, J. Stanley Durkee, over issues including pay equity between black and white faculty members and Locke’s aim to raise the profile of African American studies at the university.Harris and Molesworth, Alain L. Locke, 176–77. He was reinstated in 1928 after appealing to Howard University’s first African American president, Mordecai W. Johnson (1891–1976).

Locke spent the next twenty-five years at Howard University, deeply enmeshed in the fabric of the university community. He served as chair of the philosophy department and was integral in ensuring that the university remained at the heart of African American intellectual life.

Locke also maintained his position as a prominent figure of the African American community outside of Howard, remaining committed to aesthetic endeavors of all varieties. He worked extensively with the Harmon Foundation, whose work included supporting the work of African American artists, and, in collaboration with William Grant Still (1895–1978), he turned “Sahdji,” a short story he had published in The New Negro, into a ballet.Harris and Molesworth, Alain L. Locke, 253.

African American Art Criticism

The importance of Locke’s promotion of African American art cannot be overstated. Although Locke is well known for his analyses of black literature and performance, his role as a critic of African American art has often been overlooked. However, Locke’s work in this field was instrumental in fostering the growth of the African American art community. Specifically, he participated in adult education initiatives such as the Harlem Art Workshop and spoke for “community and government-based projects directed at the betterment of the black population.” Through such endeavors, Locke paired his criticism of African American art with an entrepreneurial spirit focused on its creation.Mary Ann Calo, “Alain Locke and American Art Criticism,” American Art 18, no. 1 (2004): 91.

Just as importantly, Locke provided the philosophical basis for movements such as the New Negro Movement, founded by Hubert Harrison (1883–1927) in 1916–17, and the Harlem Renaissance. He was instrumental in introducing African American art to both black communities and mainstream America by correcting the “misconceptions and critical distortions” of a “skeptical audience.”Calo, “Alain Locke,” 88, 91. The term “New Negro” became popular during the Harlem Renaissance (1917–28). The New Negro Movement promoted African American dignity and a refusal to submit quietly to the practices and laws of Jim Crow racial segregation. Especially Alain Locke made the term “New Negro” popular.

His pioneering work was not always logically consistent, and it was surely never easy. Locke struggled between presenting a distinct African American identity and integrating it with broader American culture. He rejected absolute conclusions on African American art in favor of an unresolved tension between divergence and unity. Locke’s response to this overlooked “minority artistic achievement” was to attempt to historicize, analyze, and classify African American art through his art criticism and philosophical writings. Locke undertook this task with almost no assistance; for a long time, he was one of only a handful of African American art critics.Calo, “Alain Locke,” 93, 91.

Locke and The New Negro

Locke’s aesthetic interests are connected philosophically and practically to his interest in democracy, racial equality, and the theory of value. Perhaps the best testament to this confluence appears in Locke’s work on the anthology The New Negro.

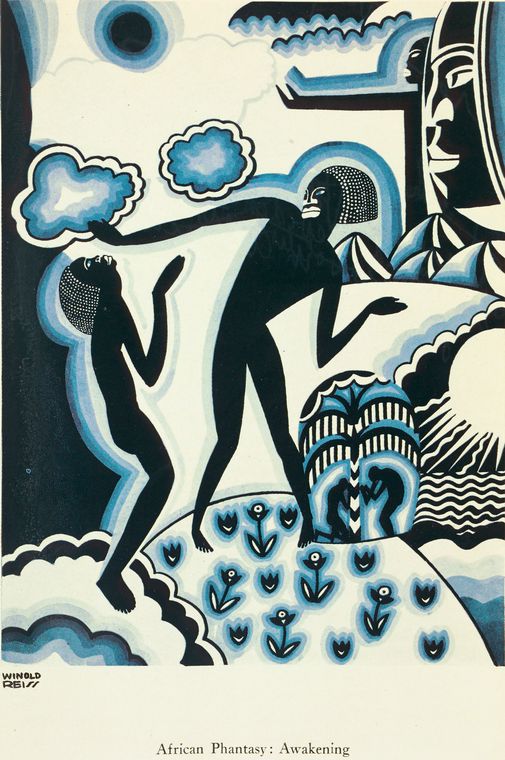

Locke’s firing from Howard University in 1925 created an opportunity for some of his most important work as a scholar and public intellectual. Locke was asked to guest edit the March 1925 issue of the magazine Survey Graphic titled “Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro,” which aimed to situate Harlem as the “Greatest Negro Community in the World.”Harris and Molesworth, Alain L. Locke, 187. Locke happily obliged, and the result was a wildly popular issue that saw wide circulation and two printings.

Locke then expanded the issue into an anthology titled The New Negro, the work for which he is best known. The anthology contained works by several of the most prominent figures of the Harlem Renaissance, including fiction by Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960), poetry and music by Langston Hughes (1902–1967), and essays by Walter Francis White (1893–1955) and W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963).Alain Locke, ed., The New Negro: An Interpretation (New York: A. and C. Boni, 1925). Locke’s part in articulating the intellectual program of the “New Negro” and Harlem Renaissance movements earned him the title “Dean of the Harlem Renaissance.”Reportedly a title given Locke by Charles S. Johnson, director of the American Urban League.

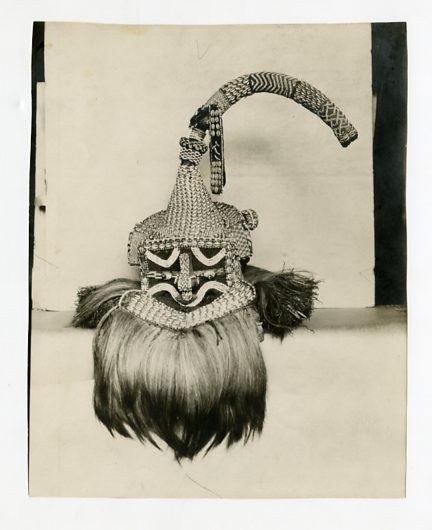

Locke wrote five essays for The New Negro, but by far the most famous of them was “The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts.” Locke championed what would have been a radical idea in his time: that the art of African civilizations possessed the same level of profound artistic achievement as the art of classical antiquity. He argued for the recognition of the aesthetic value of African art independent of its influence on European modernism and exhorted contemporary African American artists to draw inspiration from African art’s “almost limitless wealth of decorative and purely symbolic material”:Alain Locke, “The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts,” in The New Negro; reprinted in Molesworth, Works of Alain Locke, 193.

Even with the rude transplanting of slavery, that uprooted the technical elements of his former culture, the American Negro brought over as an emotional inheritance a deep-seated aesthetic endowment. And with a versatility of a very high order, this offshoot of the African spirit blended itself in with entirely different culture elements and blossomed in strange new forms.Locke, “Legacy,” in Molesworth, Works of Alain Locke, 188.

Locke’s views on art were intimately bound up in what he thought to be art’s purpose. In contrast to the approaches taken by many leaders in the African American community at the time—including W. E. B. Du Bois, who saw art as a means of collective uplift—Locke insisted that the value of art lay in its expression of the individuality of an artist. Though he hoped that the art produced by African Americans would repudiate racist beliefs, he did not view this to be its primary function. Rather, art was meant to reflect the unique perspective of the artist and, in doing so, touch on some fundamental aspect of the human experience.

It was with this in mind that Locke penned the introductory essay to the first issue of the journal Harlem, in 1928. The essay, titled “Art or Propaganda,” championed the necessity of artistic expression that transcends mere propaganda: “Art in the best sense is rooted in self-expression and whether naive or sophisticated is self-contained.” The problem with art motivated by social critique and ideals of group uplift is that “it perpetuates the position of group inferiority even in crying out against it. For it leaves and speaks under the shadow of a dominant majority whom it harangues, cajoles, threatens or supplicates.”Alain Locke, “Art or Propaganda,” Harlem 1 (1928): 12–13; reprinted in Molesworth, Works of Alain Locke, 219. In Locke’s view, art helped the cause of racial equality only when it was free to establish intellectual frameworks that were entirely independent of the demands of the majority.

Howard University Gallery of Art

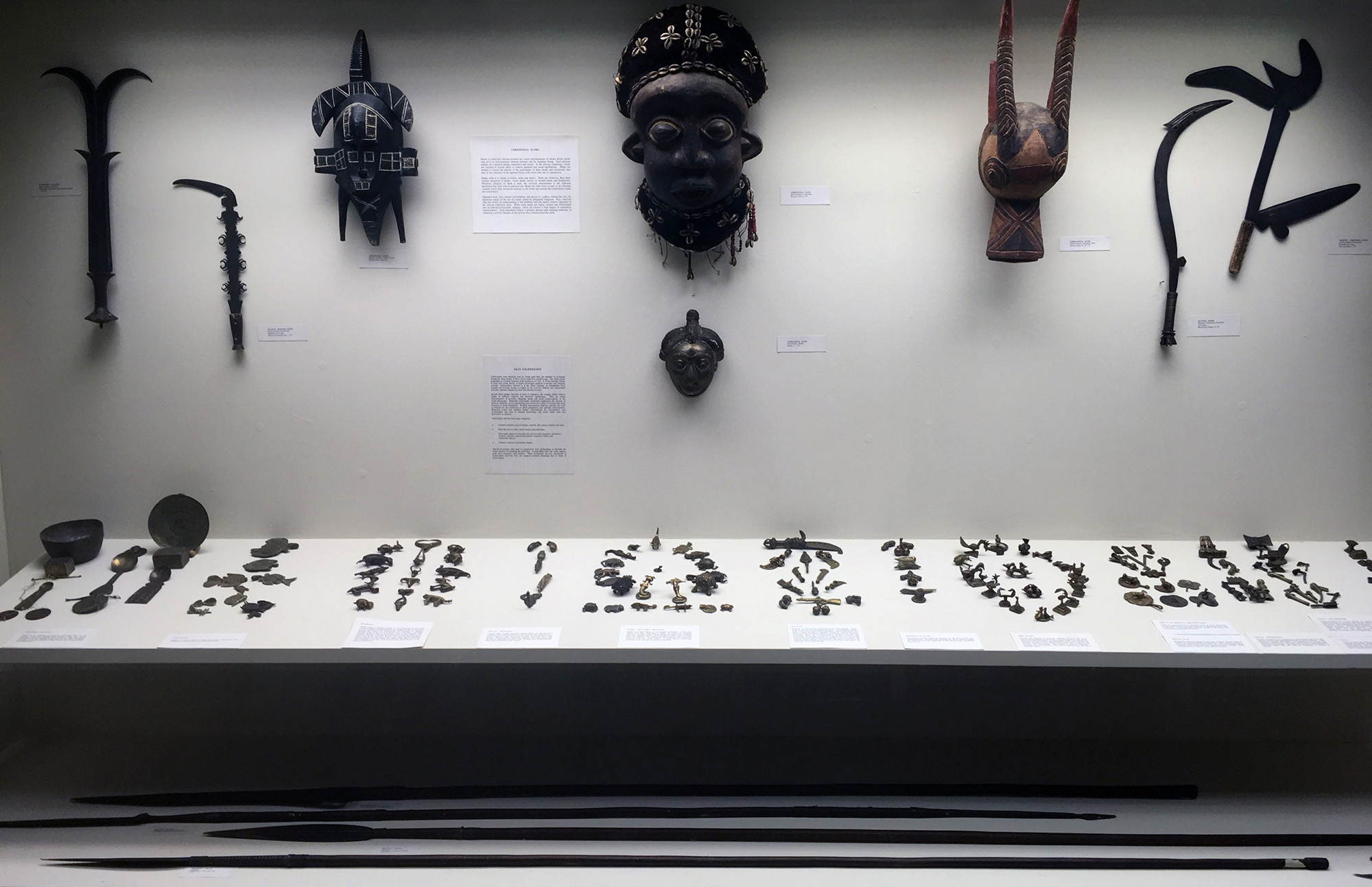

In 1928, Howard University’s board of trustees voted to create a gallery of art, whose purpose was to “make revolving exhibitions of contemporary arts and crafts available for visitation and study.”“About Us,” Howard University Gallery of Art, accessed May 5, 2017, http://www.galleryofart.howard.edu. In the inaugural year, Locke arranged for a showing of his own African art collection, titled An Exhibition of African Sculpture and Handicraft, which he hoped would prompt Howard’s students to look toward African culture for creative inspiration. This desire echoed the aesthetic philosophy outlined in Locke’s “The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts,” one of the essays in The New Negro, his highly influential work on African and African American art published in 1925. The gallery officially opened on April 7, 1930.Tritobia Benjamin, “The Howard University Gallery of Art,” The International Review of African American Art 11 (1993): 15. After the gallery opened, the artist Lois Maliou Jones (1905–1998)—who joined the Howard faculty in the gallery’s opening year—sought to incorporate motifs from African art into her own work, thereby validating Locke’s interest that contemporary black artists find inspiration in classical African art.

Locke’s Legacy

According to Mary Ann Calo, “Locke defined the possibilities and parameters of African American art and gave it a past as well as a future. Through a series of carefully constructed critical oppositions, he rendered it complex and placed it in conversation with a larger world. . . . He connected African American art to history, experience, and modern identity, and he suggested what it might contribute to the nation’s cultural capital.”Calo, “Alain Locke,” 96.

Howard University received much of Locke’s estate in 1955, a year after his death. This donation included his papers, correspondence, and the core of his collection of African art, which became an important component of Howard’s burgeoning “encyclopedic collection.”Benjamin, “Howard University Gallery of Art,” 15. His bequest “formed the basis of a teaching collection devoted to Africa’s culture,”Harris and Molesworth, Alain L. Locke, 382. a collection that has only become more important with the continued growth of the field of African American art history and the establishment of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Two years later, in 1957, the Howard University Gallery of Art staged an exhibition of parts of Locke’s art bequest at the national Black Arts Festival in Atlanta, a tribute to Locke’s influence on African American art. A subsequent donation from the Kress Foundation, named for businessman, collector, and philanthropist Samuel H. Kress (1863–1955), provided Howard with a collection of Renaissance and Baroque paintings. The Howard University Gallery of Art also holds approximately 350 works by artists such as Heinrich Golzius, Lucas van Leyden, and Jacques Callot from the 1963 gift of the Irving Gumbel Collection of European Prints and 121 pieces of African Art from the 1990 Beatrice Cummings Mayer Central and South Africa Donation.

Profile by Priyanka Menon, 2016–2017 Dumbarton Oaks Humanities Fellow, and Faye Yan Zhang, 2017–2018 Dumbarton Oaks Humanities Fellow.