The Phillips Collection

Duncan Phillips transformed his family home into an art gallery and was committed to maintaining an intimate atmosphere by displaying the collection in a series of rotating exhibitions.

It has been my policy, and I recommend it to my successors, to purchase spontaneously and thus to make mistakes, but to correct them as time goes on. All new pictures in The Phillips Collection are on trial, and must prove their powers of endurance.

Duncan Phillips

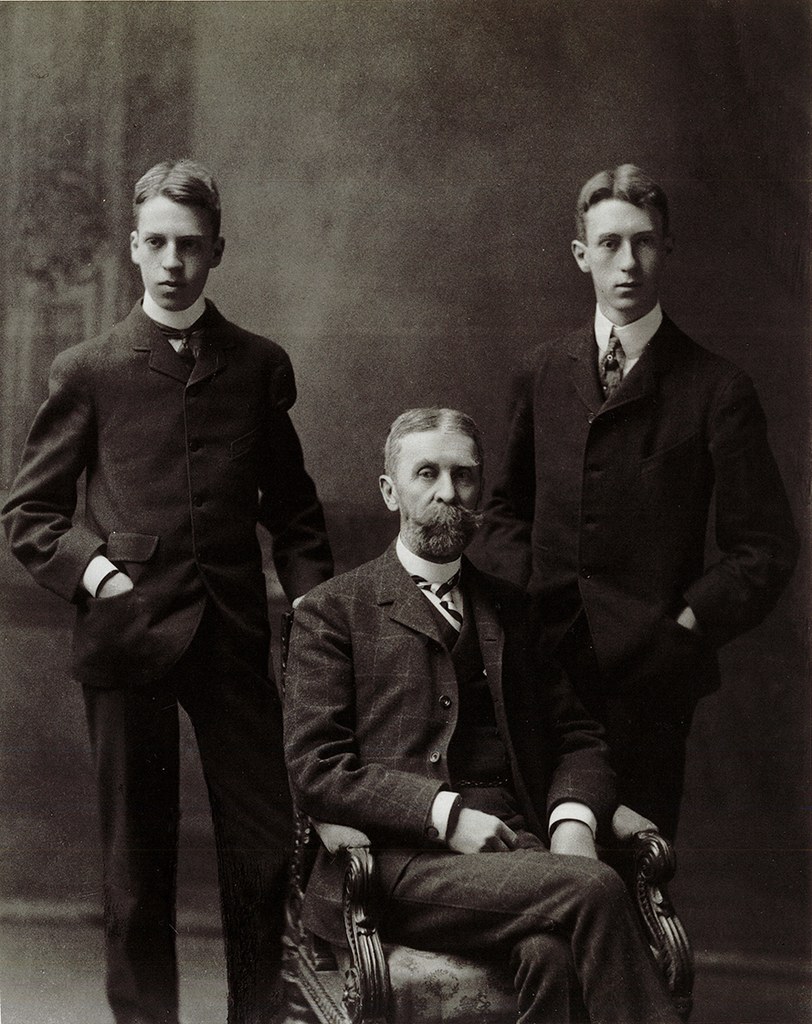

Duncan Phillips Jr. (1886–1966) was born in Pittsburgh to businessman Major Duncan Phillips and Eliza Laughlin Phillips. Duncan and his older brother, James, shared a happy childhood, spent largely in the mansion of their grandparents on the banks of the Monongahela River. In 1895, after the death of Phillips’s grandmother, Ann Irwin Laughlin, and in search of a winter milder than Pittsburgh’s, the family moved to Washington, D.C. Almost immediately upon arriving, they began construction on the home that would eventually contain the Phillips Collection.

In 1904, the Phillips brothers began their education at Yale University. Duncan studied English and served as editor of the Yale Literary Magazine, in whose pages he wrote the article, “The Need for Art at Yale.” In what would prove to be “an omen of his future career,”Marjorie Phillips, Duncan Phillips and His Collection, rev. ed. (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1982), 36. Find out more about the Phillips Collection on its website, http://www.phillipscollection.org/ Duncan advocated in favor of offering more art history courses, believing them to be a crucial element of a liberal arts education. “To know the great pictures and the great sculpture of the ages,” he wrote, “is invaluable to the formation of a respectable standard of public taste.”Phillips, Duncan Phillips, 37.

The brothers graduated from Yale in 1908 and entered an elite circle of Ivy League–educated art enthusiasts. They spent their money on contemporary American paintings to display in their apartment, and, in 1914, Duncan published his first book, The Enchantment of Art.Phillips, Duncan Phillips, 48. After convincing their parents to set aside a small percentage of their income for the acquisition of art, the Phillipses’ collection began to expand rapidly.Phillips, Duncan Phillips, 57.

A Memorial Gallery

Then, tragedy struck. In quick succession, Duncan Phillips lost his role model and his best friend. In 1917, his father died suddenly and, fifteen months later, in 1918, his brother contracted Spanish influenza and passed away.

To cope with his grief, Phillips resolved to build a memorial for these two important figures in his life. In Phillips’s view, “no mortuary monument, remindful of the accident of death would adequately commemorate” the two men. In contrast, a gallery was “a joy-giving, life-enhancing influence” and would function as a “beneficent force in the community.” With the support of his mother and his wife, the artist Marjorie Acker, he incorporated the Phillips Memorial Gallery in 1918. In 1921, the gallery opened to the public.Phillips, Duncan Phillips, 60.

The gallery was located in a portion of the Phillips’ family home in Dupont Circle, which lent the space a unique atmosphere. Here, the domestic merged seamlessly with the public.W. G. Constable, “Duncan Phillips,” The Burlington Magazine 108, no. 761 (August 1966): 429. The deeply personal motivation for the institution’s founding meant that it maintained a feeling of familiarity even as the Phillipses welcomed strangers into their home.

A Home for the Fine Arts

Upon the gallery’s opening, Phillips wrote, “It is to be a home for the fine arts and a home for all those who love art.”Duncan Phillips, “The Phillips Memorial Art Gallery,” The Art Bulletin 3, no. 4 (June 1921): 147. He prioritized the preservation of the domestic character of the gallery. Phillips did not want the walls to become overcrowded, and demanded that the building remain small even as the collection grew.

To accommodate the growing collection of the gallery, Phillips encouraged alternating exhibitions. He did not expect his collection to compete with the larger and greater museums that had much larger collections, and he wanted the gallery to be understood as a private collection and an unorthodox museum.Phillips Collection, The Phillips Collection in the Making: 1920–1930, (Washington, D.C.: The Phillips Collection, 1979), 27. It was to be an “experiment station.”Phillips, “Phillips Memorial Art Gallery,” 148. Explaining this concept further, Phillips wrote, “It has been my policy, and I recommend it to my successors, to purchase spontaneously and thus to make mistakes, but to correct them as time goes on. All new pictures in The Phillips Collection are on trial, and must prove their powers of endurance.”Phillips Collection, Phillips Collection in the Making, 5.

Phillips invited special friends and acquaintances—including artists, dealers, critics, and professors—to join the gallery’s committee of trustees.Sue Frank, curator, The Phillips Collection, interview by Melda Gurakar, 2016. The museum would maintain an administrative team, including a financial adviser and treasurer, but never a board. This team did not influence the acquisitions for the collection; Phillips would often only consult his wife when making purchases.Frank, interview by Gurakar. It was also important to Phillips that the museum remain self-sufficient and that it not rely on wealthy donors.

“A Collection of Modern Art Second to None”

Phillips collected works by a wide range of artists, including El Greco, Goya, Daumier, Courbet, Manet, Renoir, Degas, Cézanne, Mooney, Pissarro, and Van Gogh.Constable, “Duncan Phillips,” 429. One of the first important works that Phillips purchased for the gallery, in 1923, was Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party. Phillips was so drawn to the work that he did not balk at the record asking price of $125,000. He believed it would be a cornerstone of the collection, establish the museum's importance, and draw people from far and wide to see it, saying that it “will put us on the map as a collection of modern art second to none anywhere!”Elizabeth Hunter Turner, Duncan Phillips Collects: Paris between the Wars (Washington, D.C.: Phillips Collection, 1991), 14.

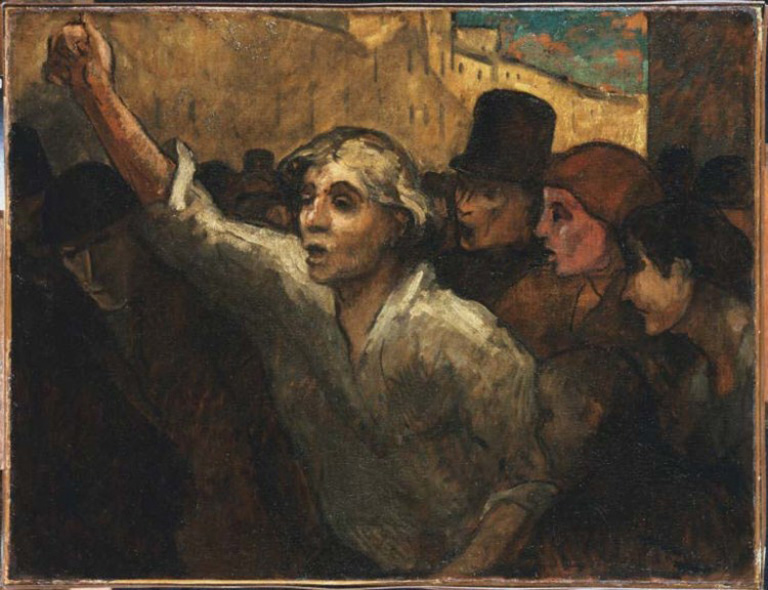

Phillips generally preferred purchasing from artists who eschewed popular standards to follow their own tastes.Frank, interview by Gurakar. Phillips looked for six qualities: intense sensibility, self-reliance, self-discipline, tolerant humanity, universality, and essentialism.Duncan Phillips, The Artist Sees Differently (Baltimore: Norman T. A. Munder and Co., 1931), 26. Other important purchases included Daumier’s Uprising, in 1924, and Cézanne’s Mont Sainte Victoire, in 1925. During a period of isolationism in the aftermath of the First World War, the institution was one of very few American museums purchasing French art.

Phillips soon found, however, that he did not have consistent funds with which to purchase the pieces he wanted for the gallery. Therefore, in the 1930s, he began to trade works from the collection for new ones. “It is a collection in the making,” Phillips noted. “Changes are inevitable. And whenever we are under unusual financial strain there is only one thing for us to do—and that is to sell.”Phillips Collection, Phillips Collection in the Making, 17. Further, he did not consider his purchases to be final; he purchased spontaneously and then tested pieces in the collection to decide whether or not he would keep them.Phillips Collection, Phillips Collection in the Making, 5.

A Force against Conformity

From its inception, the gallery reflected a commitment to artists. It embodied Phillips’s philosophy that collecting art was a means of enriching life and increasing understanding and sensibility.Phillips Collection, Phillips Collection in the Making, 9. Phillips also espoused a strongly pluralistic conception of the arts and worked to encourage diversity in modes of expression. Phillips, Artist Sees Differently, 29. He saw artistic individuality as a force against conformity.Phillips, Artist Sees Differently, 4.

Phillips also believed he had a responsibility as an art collector to support and encourage artists and their experimentation, offering them not only financial support, but also friendship.Constable, “Duncan Phillips,” 429. Working closely with artists like those affiliated with the Société Anonyme, founded by Katherine Dreier, Man Ray, and Marcel Duchamp, Phillips often bought works by a single artist. Although the vast majority of Dreier’s collection was bequeathed to Yale, she elected to leave some of the choicest works in the collection to the Phillips upon her death in 1953.

Although Phillips was perhaps instinctively a traditionalist, he appreciated alternate traditions and maintained a wide variety of art in his gallery. Phillips’s taste evolved throughout his life and remained independent of popular trends, as he read and studied aesthetics extensively.Turner, Duncan Phillips Collects, 9.

Despite his open-mindedness, Phillips was initially disinclined to look favorably upon avant-garde art, deriding it as excessively enamored of replicating the inhumane machine culture from which he believed art ought to liberate mankind. He even despised the work of Matisse in a 1913 magazine article, calling it “unworthy of the mere ignorance of little children and benighted savages” and “not only crude but deliberately false, and insanely, repulsively depraved.”Duncan Phillips,“Revolutions and Reactions in Painting,” International Studio (December 1913): 128–29, quoted in George Heard Hamilton, “A Collection in the Making,” in The Eye of Duncan Phillips: A Collection in the Making, ed. Erika Passantino and David W. Scott (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 26. By the 1920s, though, Phillips had changed his view and had begun to accept and appreciate modernism.Turner, Duncan Phillips Collects, 9.

In 1957, Phillips purchased his first painting by Mark Rothko. Phillips then created a signature space in the museum, known as the “Rothko Room,” which became a permanent installation.Frank, interview by Gurakar. The small room was furnished with only a single bench and meant to invoke the atmosphere in which Rothko had intended his works to be viewed. Rothko himself visited the space and highly approved of Phillips’s method of displaying his artwork.

He displayed the rest of his collection in rotating exhibits, which often juxtaposed pieces from different times or cultures. (For example, he placed works of art as different as an ancient Egyptian bust and a painting by Augustus Vincent Tack next to each other.Phillips, Artist Sees Differently, 100.) Phillip wrote that this juxtaposition resulted “not in eclecticism . . . but rather in an intimate unity of effect.”David W. Scott, “The Evolution of a Critic: Changing Views in the Writings of Duncan Phillips,” in Passantino and Scott, Eye of Duncan Phillips, 22. He also comprised “units” of paintings by the same artist, which he then hung together. Artists collected in this manner include Daumier, Bonnard, Dove, Marine, and Bracque, and smaller units included Degas, Delacroix, Van Gogh, Twachtman, Cézanne, and Picasso.Phillips, Duncan Phillips, 191.

The Phillips Gallery

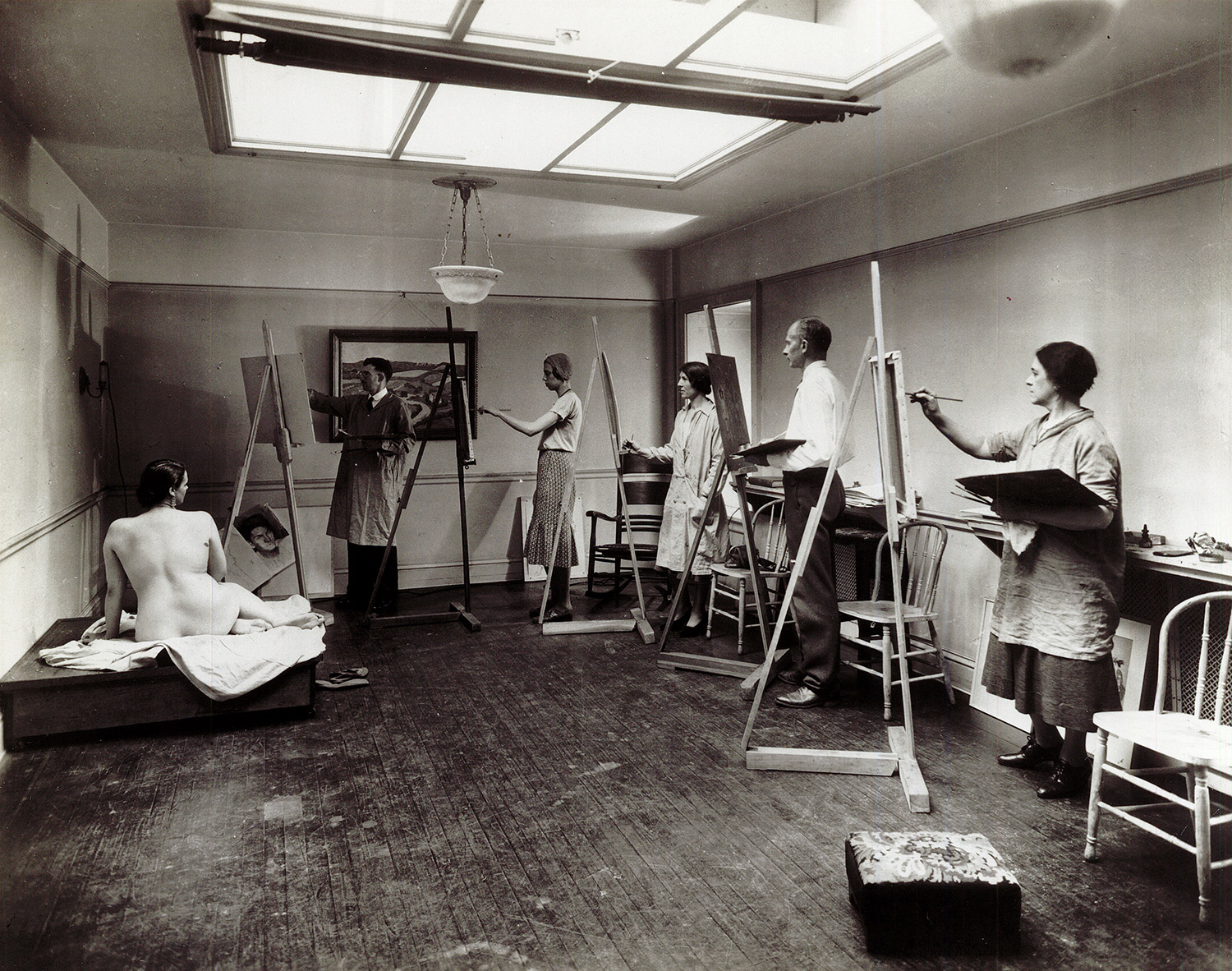

For the 1921 opening, Lawrence Grant White of the new York City architectural firm McKim, Mead & White designed a second-floor main gallery addition. Upon opening, the gallery received a great response from the public. The response was so enthusiastic that, although he initially only opened the second-floor main gallery, by the end of the decade, Phillips decided to turn his entire house into a gallery.Phillips Collection, Phillips Collection in the Making, 11. A fourth-floor studio with skylight was added by the architect Frederick H. Brooke in 1923, and, in 1931, one of his college friends, C. Law Watkins, established the Phillips Gallery Art School on this floor. In 1941, the Phillips also began hosting a chamber music series in what was formerly the library. Phillips wrote that the series was “in complete accord” with his art philosophy of “adding the contemporary to the classic,” and it continues to this day.Phillips, Duncan Phillips, 304.

Although the original home that Phillips lived in is still used for exhibitions, a new wing, today known as the Goh Annex and designed by Frederic Rhinelander King of the New York City architectural firm of Wyeth & King, opened to the public in 1961. In keeping with Phillips’s vision, the addition maintains the intimacy of the private collection while allowing the gallery to grow and exhibit new artists’ works. Phillips planned the hanging of every painting in the new wing.Frank, interview by Gurakar. In his review of the new addition, Frank Getlein wrote: “What you will see will be a small masterpiece of modern museum design and a rare example of quiet brilliance in the installation of art for public view.”Frank Getlein, Sunday Star, April 9, 1961. The main galleries and the annex were completely renovated in 1983. Between 2002 and 2006, an adjacent apartment building was incorporated into the Phillips Collection and renovated as museum space by the Washington, D.C., architectural firm of Cox Graae + Spack. Named the Sant Building, this expansion doubled the Phillips Collections’ square footage.

Phillips served as director of the museum until his death in 1966. He was succeeded by his wife, who served as director until 1972, when the couple’s son, Laughlin took over the museum’s directorship.

Profile by Melda Gurakar, Melissa Rodman, Joy Wang, and Leah Yared, 2016 summer interns.