The Washington School of Ballet and The Washington Ballet

Mary Day founded the Washington School of Ballet in 1944 and the Washington Ballet in 1976. With her uncanny eye for detail and clear vision for excellence, Day brought dance to the forefront of Washington’s burgeoning arts scene.

To me, teaching under the heading of ballet always meant more than just movement or technique. It meant the development of the student as a whole person.

Mary Day

Mary Day (1910–2006) grew up in Washington’s Foggy Bottom neighborhood as the youngest of four siblings.Elvi Moore, ed., Mary Day: Grande Dame of Dance in the Nation’s Capital (2009), 14. Other than her father’s recreational violin playing, Day’s home was not steeped in the arts. However, when she began studying ballet at the age of eleven, Day showed promise not only as a dancer but as an organizer, displaying a precocious knack for choreographing and teaching other children her own age. She later reminisced:

My favorite pastime was to gather neighborhood children and “choreograph” little dances, which we presented to interested parents in our back yard. I never participated in these shows. Instead, I looked on with pride at my friends dancing what I had taught them to do.Moore, Mary Day, 17.

At age fifteen, Day began attending the King Smith School in Washington to study with Lisa Gardiner (ca. 1896–1958), who had danced in the company of legendary Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova. At Gardiner’s encouragement, Day moved to England to study at the Royal Academy of Dance. Day eventually moved back to the Washington area, and she began giving private dance lessons in Chevy Chase and choreographing children’s ballets at local high schools.Moore, Mary Day, 19–21.

Beginnings of the School

Day’s classes soon outgrew her Chevy Chase studio, and she joined forces with Gardiner to create a new school, with Day teaching the children while Gardiner took on the professional and adult classes. They rented a studio at the corner of Windom Place and Wisconsin Avenue, and the Washington School of the Ballet opened its doors in 1944. In 1948, the school relocated to 3515 Wisconsin Avenue, which still houses classes for the school and serves as the main campus today. Day and Gardiner converted the downstairs into a studio and small office and turned the upstairs into an apartment for themselves.Moore, Mary Day, 23–25. Day and Gardiner led the school together until Gardiner died in 1958.Moore, Mary Day, 31.

Early in the school’s history, Day organized collaborations with other D.C. arts groups that established the Washington School of Ballet as a fixture in the city’s arts scenes. The school first partnered with the Children’s Theatre of Washington in April 1947, staging a production titled Adventures in Oz.Moore, Mary Day, 23–26.

The school’s first collaboration with the National Symphony Orchestra took place in 1950 for a production of Hansel and Gretel, under the direction of the orchestra’s new music director, Howard Mitchell, who had enrolled his daughters in Day’s classes.Moore, Mary Day, 23–26. To Day’s surprise, the five thousand seats at Constitution Hall were sold out two weeks in advance. The production’s success established the Washington School of Ballet’s reputation, paving the way for a strong partnership between the school and D.C.’s premier orchestra.

Day’s teaching style groomed dancers with a sense of clarity and musicality. Day described what separated her dancers from the rest of the pack:

They come out of the school with a certain look . . . a certain pull of the muscles, a certain pureness of training, a certain carriage of the head. It’s been with the school for a long time, you know, it’s in the rafters, really, in the wood. Their flow of line and the cleanness of their various positions. People can usually spot them.Leslie Marshall, “Mother Courage,” Washington Post, November 20, 1983.

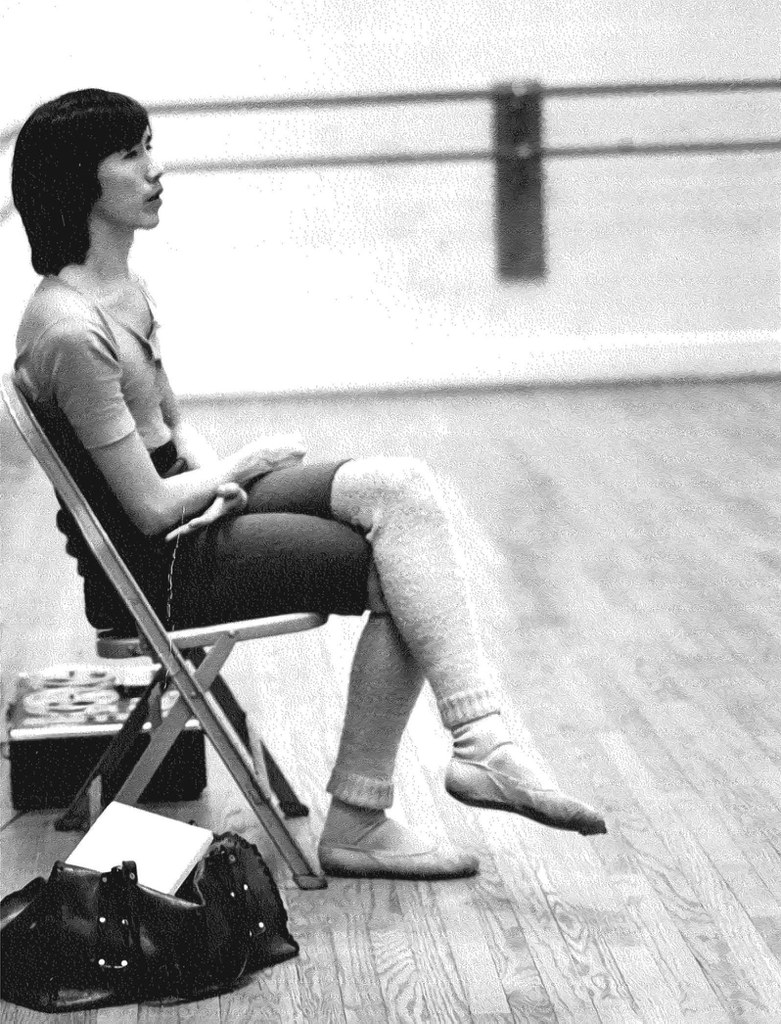

In the studio, Day achieved notoriety for her eagle eye, which could spot the tiniest of imperfections in a dancer’s posture. Judith Keyserling, the Ballet’s former director of marketing, quipped that “from the back of the auditorium, [Day] could see a pointe shoe that wasn’t tied properly.”Patricia Sullivan, “Ballet School Founder With an Eye for Talent,” Washington Post, July 12, 2006. For Day, it was these details that made the difference in a ballerina’s comportment: “Training has to be rather microscopic you know. . . . The small details—when you’re finally grooming them at the end, the small details are very important.”Marshall, “Mother Courage.”

Over the years, the Washington School of Ballet became nationally recognized as a training ground for world-class dancers, including Kevin McKenzie, Amanda McKerrow, and Virginia Johnson. Others who graduated from the school include the actress Shirley MacLaine and two presidents’ daughters, Chelsea Clinton and Caroline Kennedy.“Alumni,” The Washington Ballet, accessed June 28, 2018, https://www.washingtonballet.org/alumni.

Putting the Washington Ballet on the Map

In 1956, productions of the Washington School of Ballet began using the name “The Washington Ballet,” though it would not officially become a professional company until 1976. Also in 1956, Day invited Frederic Franklin, who had been premier danseur with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, to coach the production Les Sylphides. Franklin stayed with the company and was named artistic codirector alongside Day the following year.Moore, Mary Day, 28–29.

Franklin and Day’s differences in vision for the ensemble led to a rift in leadership. Franklin wanted to turn the school into a full-fledged professional ballet company. Day, however, wanted to continue focusing on the school. When the Ballet’s board decided to delay becoming a fully professional company in March 1961, Franklin resigned to form the National Ballet, which ultimately folded for financial reasons in 1974.Moore, Mary Day, 34–35.

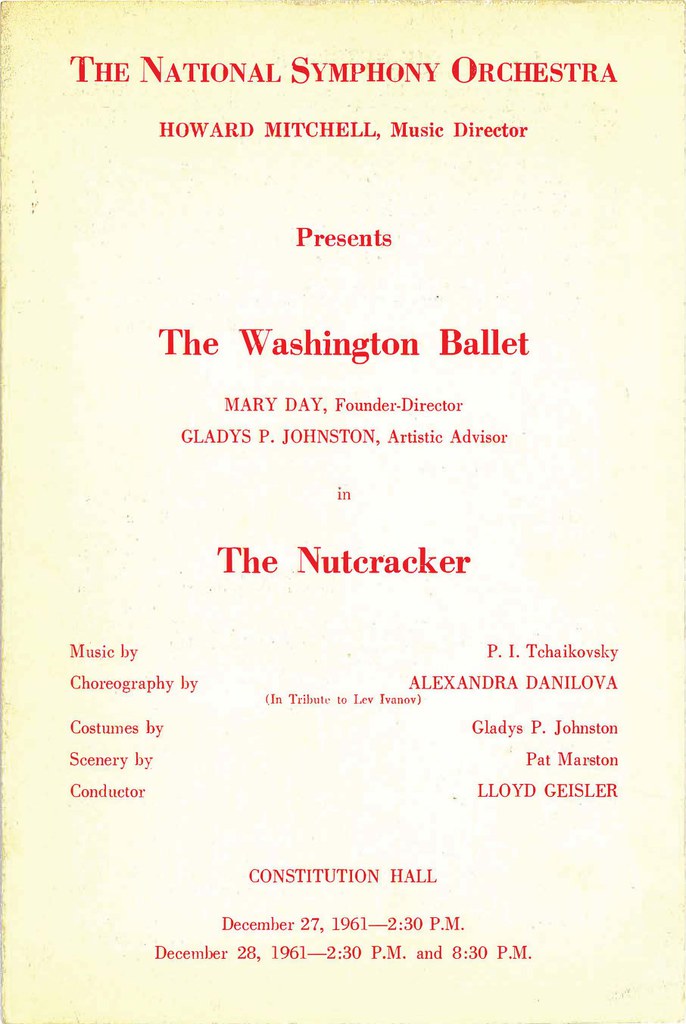

In December 1961, the Washington School of Ballet staged its first Nutcracker at Constitution Hall, accompanied by the National Symphony Orchestra, under the direction of Lloyd Geisler.Jean Battey, “Nutcracker Ballet Setting Sparkles,” Washington Post, December 28, 1961. Day brought in established dancers for the production, and the choreography was set by Alexandra Danilova, the former prima ballerina of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.Jean Battey, “Washington Ballet Twirls Into a ‘Nutcracker’ Spin,” Washington Post, December 17, 1961. The Washington Ballet’s Nutcracker has since become a beloved holiday tradition for Washingtonians.

In 1962, Day opened the Academy of the Washington School of Ballet.Jean Battey, “Dance and Academics Perform Pas de Deux,” Washington Post, October 7, 1962. After visiting the Soviet Union on a State Department–sponsored trip, Day created the Academy in the image of ballet academies like Moscow’s famed Bolshoi Ballet School.Moore, Mary Day, 41. The Academy became the first combined program of ballet training and academic education in the United States.Battey, “Dance and Academics.” At its peak, the school enrolled 120 students, and it accommodated boarding students with dormitories near the academic building.Moore, Mary Day, 42. The Academy operated until it closed in 1977 for financial reasons.Moore, Mary Day, 46.

The Washington Ballet

For decades, the absence of a Washington-based ballet company meant that talented alumni of the school would leave the city for professional companies. Thus, at the urging of several parents, Day founded the professional Washington Ballet in 1976, aided by subsidies from the National Endowment for the Arts.Moore, Mary Day, 47.

Day intended for the Washington Ballet to remain a chamber ensemble, smaller in number than professional troupes in other large cities such as New York’s American Ballet Theatre. While this prevented the company from staging larger and more classical productions, it pushed the troupe to distinguish itself by staging more experimental works.

The Washington Ballet’s first resident choreographer, Choo-San Goh (1948–1987), who worked with the Ballet from the company’s founding until his death, aided this push toward less conventional works.Jennifer Dunning, “Choo San Goh, a Choreographer Hailed for Inventive Dance Forms,” New York Times, November 30, 1987, https://www.nytimes.com/1987/11/30/obituaries/choo-san-goh-a-choreographer-hailed-for-inventive-dance-forms.html. Goh created thirty-four ballets in his lifetime, fourteen of them for the Washington Ballet.Alan M. Kriegsman, “Choo-San Goh’s Legacy of Joy,” Washington Post, December 1, 1987, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1987/12/01/choo-san-gohs-legacy-of-joy/1e3427ed-45ff-41f7-952f-005cff202517. Goh’s distinct style, which emphasized technique and musicality over plot, brought out the dancers’ strengths that Day had cultivated in her studio. Goh blended eastern movement with classical ballet technique, and dancers and critics alike praised Goh’s innovative productions.Moore, Mary Day, 49.

Students and dancers also succeeded in international competitions. In 1972, Day brought two students to the Varna International Ballet Competition in Bulgaria; Kevin McKenzie won a silver medal, and Suzanne Longley won bronze.Moore, Mary Day, 10. And in 1981, Amanda McKerrow, an apprentice at the Washington Ballet, won a gold medal at the fourth Moscow International Ballet Competition.Carla Hall, “Ballet’s Day In the Sun,” Washington Post, July 5, 1981. This unprecedented win—the first American gold medal at an international competition—catapulted Day and the Washington School of Ballet to international stature. In 1983, Choo-San Goh also won a choreography award at the Varna International Ballet Competition.Dunning, “Choo San Goh.”

Transitions

After Goh’s death in 1986, the ballet drifted through a handful of choreographers and artistic associates, but as the Washington Post’s Sarah Kaufman reported, “The Washington Ballet simply couldn’t keep up the artistic momentum Goh created.”Sarah Kaufman, “The Ballet’s Next Step,” Washington Post, January 4, 1998.

In 1997, Day announced a search for a new artistic director, and the board of directors chose Septime Webre, the former head of the American Repertory Ballet in New Brunswick, New Jersey, as Day’s successor beginning in the fall of 1999.Sarah Kaufman, “Washington Ballet’s Shoe-In,” Washington Post, August 31, 1998. Day stayed on as the school’s director until 2004.Patricia Sullivan, “Ballet School Founder with an Eye for Talent,” Washington Post, July 12, 2006.

Webre came to the Washington Ballet with the immediate and clear goals of raising the company’s profile in D.C. while maintaining its classical style. But Webre’s chief goal was to engage the local community in the company’s work.Kaufman, “Washington Ballet’s Shoe-In.” By nurturing relationships between the Washington Ballet and the D.C. community, Webre hoped to bring ballet to a wider swath of audiences. Even before starting the job, Webre asserted that “the only way Washington Ballet can be successful is by being a meaningful part of the cultural fabric of the city.”Sarah Kaufman, "Jumping Right In: Septime Webre Leaps Into His New Job as Director of the Washington Ballet," Washington Post, May 29, 1999, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1999/05/29/jumping-right-in/50144ec6-75c4-44d8-a84a-d9a3b27eb166.

Under Webre’s leadership, the Washington Ballet launched outreach programs that introduced ballet to communities underrepresented in the arts. In 1999, the Washington Ballet launched a program called DanceDC, which brought ballet and dance to underresourced communities in the city. DanceDC partners with D.C. schools and integrates the ballet program with the school’s academic curriculum. In addition, the Excel! scholarship selects a handful of DanceDC students each year to receive full merit-based scholarships at the school.“Community: About,” The Washington Ballet, accessed July 17, 2018, https://www.washingtonballet.org/about-community.

In the summer of 2005, the Washington Ballet began partnering with the Town Hall Education Arts Recreation Campus (THEARC), a community arts space in the Anacostia neighborhood. The Ballet opened a studio and performance venue at the THEARC, which now functions as one of the school’s two main campuses. THEARC has provided students with “a space, access, and opportunity to come in and train at a facility that is top-of-the-line.”The Washington Ballet, “Community Engagement at THEARC – The Washington Ballet,” June 5, 2015, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0VktO_a54U.

At times, Webre’s ambition for the Washington Ballet pushed the dancers past their limits. As a result, the dancers signed on with the American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA), citing intense rehearsal standards and frequent injuries as the reasons for taking this action.Jacqueline Trescott, “Labor Dispute Jeopardizes Ballet Troupe’s ‘Nutcracker,’” Washington Post, December 14, 2005, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/12/13/AR2005121302003.html. During the 2004–2005 season, the Ballet’s administration did not agree to a contract by AGMA outlining health and safety concerns, leading to a mid-run cancellation of the company’s classic Nutcracker.Sarah Kaufman, “Washington Ballet Cancels ‘Nutcracker’ Run,” Washington Post, December 17, 2005, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2005/12/17/washington-ballet-cancels-nutcracker-run/cb3ea0d7-871f-4769-aa97-dda477dc1ee8. After three months of negotiations, the company announced that it had agreed on a contract with AGMA.Sarah Kaufman, “Dancers, Company Agree on Contract,” Washington Post, March 7, 2006.

Since September 2016, Xiomara Reyes has led the Washington School of Ballet,Sarah Kaufman, “ABT Ballerina Xiomara Reyes to Lead Washington School of Ballet,” Washington Post (June 16, 2016), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/arts-and-entertainment/wp/2016/06/16/abt-ballerina-xiomara-reyes-to-lead-washington-school-of-ballet. and in July 2016, Julie Kent, a former principal dancer with the American Ballet Theatre, succeeded Webre as the ballet’s artistic director.Michael Cooper, “Julie Kent to Lead Washington Ballet,” New York Times, March 7, 2016, https://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/03/07/julie-kent-to-lead-washington-ballet. Kent has shifted the ballet back to its more classical roots. According to the Washington Post’s Sarah Kaufman, Kent “has a ballerina’s eye for subtlety and detail, and for the small charms that can captivate and hold an audience”—much like Mary Day’s own discerning eagle eye.Sarah Kaufman, “Julie Kent, Sweeping the Washington Ballet Forward,” Washington Post, September 28, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/theater_dance/julie-kent-sweeping-the-washington-ballet-forward/2016/09/28/659ee7aa-7930-11e6-bd86-b7bbd53d2b5d_story.html.

Profile by John Lim, 2018 summer intern