Washington National Opera

Begun as the Opera Society of Washington in 1957 by a cohort of Washington-area musicians and enthusiasts, today the Washington National Opera performs at the Kennedy Center, where its world-class productions and educational outreach and artist development programs sustain the vision of founders Day Thorpe and Paul Callaway.

“[The Opera Society of Washington] would try to create a new public whose enjoyment would be the Society’s sole, undivided interest.”

Day Thorpe, 1956

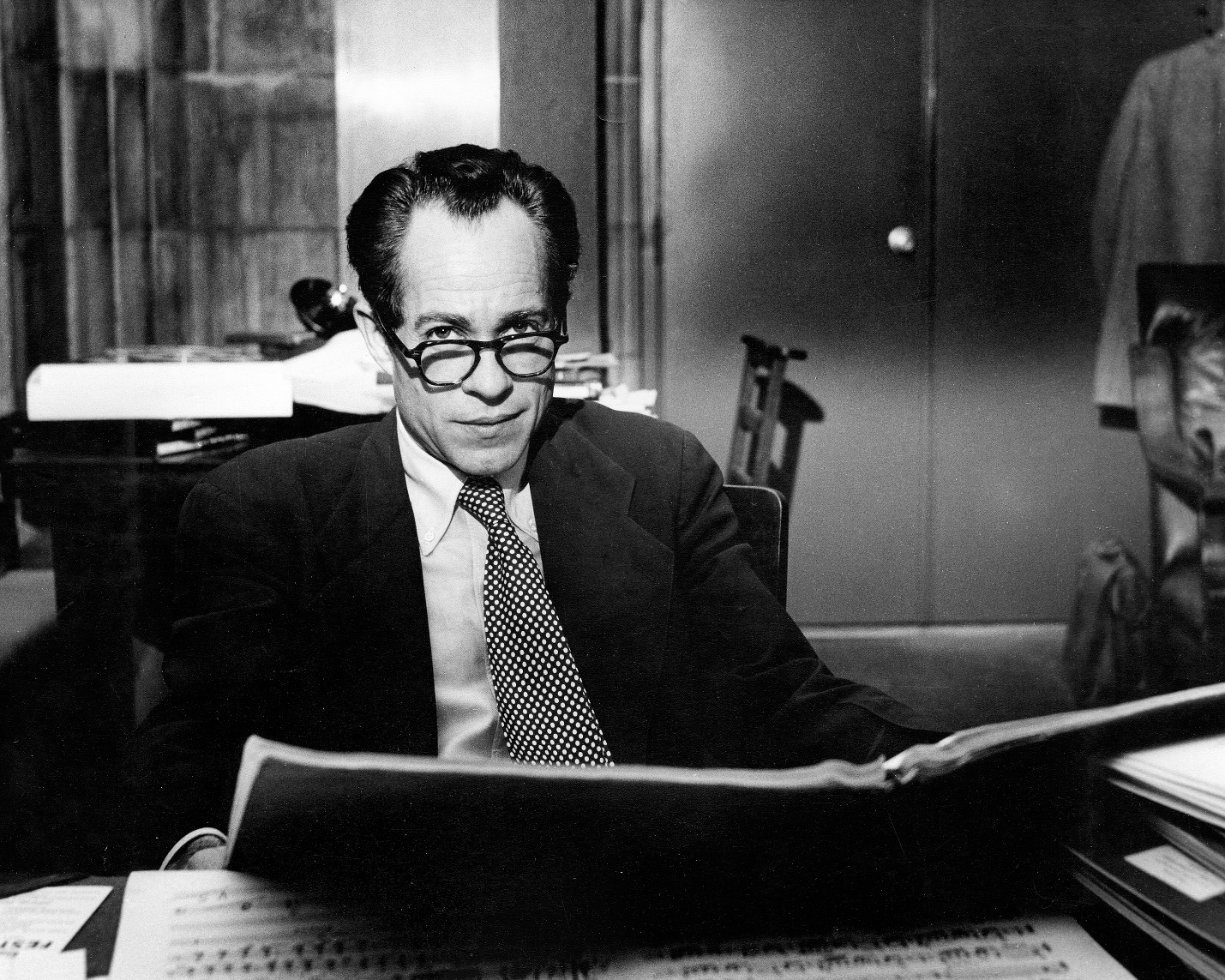

George Day Thorpe (1913–1982) was born in Lawrence, Kansas, the son of Merle Thorpe, a journalist, lecturer, and author. Shortly after Thorpe’s birth, the family moved to the Hollin Hall estate in Alexandria, Virginia,“Merle Thorpe, Editor, Is Dead Here at 76,” Washington Post and Times Herald, November 1, 1955, 1. where he grew up and was musically inclined from an early age.“Pupils at Sidwell Told of Near East,” Washington Post, March 13, 1926, R11. Thorpe graduated from Yale University in 1936, and after a tour of Europe that cemented his love for the performing arts, he followed in his father’s journalistic footsteps.“Deaths: Day Thorpe, 68,” Washington Post, March 18, 1982, C19; Mary Jane Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 1956–2006 (Tokyo: Toppan Printing, 2005), 17.

Thorpe was social, well-connected, and “loved all the good things about life.”Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 17. He founded and published the Bethesda Journal beginning in 1939.“Home Decoration Prizes Posted,” Washington Post, December 22, 1940, R2; “About Bethesda Journal (Bethesda, Md.) 1939–1950,” Library of Congress: Chronicling America, accessed July 12, 2018, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89060157. After working in advertising for some time, Thorpe began writing music reviews for Washington’s then-foremost paper, the Evening Star, and he became head music critic in January 1954.“Miss Alice Eversman Retiring,” Washington Evening Star, January 5, 1954, A6. He wrote reviews for the Evening Star for another two decades until his retirement in 1975, though in 1960 he switched to book reviews.Irving Lowens, “A Critic’s Farewell: Of Music, Mirrors and News,” Washington Evening Star, September 3, 1978, B1. His leadership legitimized the Evening Star’s music department, and when Thorpe left the position, the Evening Star’s music department “was well on its way to a well-deserved national reputation.”Lowens, “A Critic’s Farewell.” Thorpe remained well-connected in society, maintaining various club memberships that often overlapped with the musically inclined, including Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss and Mr. and Mrs. Gregory Smith.“Day Thorpe, 68”; Marie McNair, “Almanac’s for City Folk, Too,” Washington Post and Times Herald, June 7, 1957, C21.

The son of a clergyman, Paul Callaway, OBE (1909–1995) was born in Atlanta, Illinois, and demonstrated considerable musical talent from an early age. He began his musical career at thirteen as an organist for a local church in Illinois before attending and graduating from the Missouri Military Academy.Kitty Yang, “A Musical History of Washington National Cathedral, 1893–1998” (PhD diss., Peabody Conservatory of Music, 1998), 39; “Paul S. Callaway, OBE,” Washington National Cathedral, accessed July 10, 2018, https://cathedral.org/staff/paul-s-callaway-obe. He attended Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, but left after two years to study under T. Tertius Noble, then organist and choirmaster at Saint Thomas Church in New York City. Noble later remarked that “there was nothing he could ever tell Paul . . . because he was already in total command of the instrument.”“Paul S. Callaway, OBE,” Washington National Cathedral. At age twenty-two, Paul passed the fellowship examination of the American Guild of Organists, the highest professional certification the organization offers.“Callaway Becomes Cathedral Organist on September 1,” Washington Post, July 2, 1939, A5.

In 1939, when the Washington National Cathedral’s organist left, Noble enthusiastically recommended his star student to the position. Callaway hoped to use his new position “to make of Washington Cathedral a citadel of glorious church music.”Yang, “A Musical History,” 42. He did that and more, becoming a highly sought-after musician, conductor, and organist in the postwar years, exercising a musical influence on the D.C. music scene that led colleagues to liken him to Arturo Toscanini.Paul Hume, “Callaway May Be Another Toscanini,” The Cathedral Age 39, no. 4 (1964) (Washington National Cathedral Archives).

After returning from service in the Second World War, in addition to his regular church duties, Callaway directed the National Cathedral Choral Society in large-scale choral repertoire, including that of Verdi, Mahler, and Elgar. However, he also programmed contemporary and sometimes avant-garde works, such as those of Leo Sowerby, Lee Hoiby, and John LaMontaine.Paul Hume, “Callaway, the Master Music Maker,” Washington Post, April 10, 1977, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1977/04/10/callaway-the-master-music-maker/023a664c-d9c3-4dc0-95f3-bb4de3e8cdbd/?utm_term=.77cf37ef5117. He also led ensembles at the Library of Congress (for the premiere of Gian Carlo Menotti’s opera The Unicorn, the Gorgon, and the Manticore) and at Dumbarton Oaks, where he conducted nine concerts between 1948 and 1961, including an all-Handel program with the soprano Joan Sutherland on February 7, 1961.Hume, “Another Toscanini”; Hume, “Master Music Maker.” He worked with Samuel Barber on his Toccata festiva for organ, which he premiered with the Philadelphia Orchestra.Hume, “Master Music Maker.”

Opera for the Nation’s Capital

In the 1950s, Washington was “the only major capital in the civilized world without an extended opera season.”Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 45. To remedy this situation, in late 1956, Thorpe and Callaway, who had met at a Cathedral organ recital and become fast friends, merged their musical, social, and cultural contacts and founded the Opera Society of Washington, a nonprofit corporation dedicated to “giv[ing] Washington audiences operas which can be compared with any productions in the world.”Paul Hume, “City to Have Its Own Opera Company; 1st Performance Scheduled Jan. 31,” Washington Post, October 1, 1956, 1. The society’s first president, E. R. Finkenstaedt, a retired stockbroker, was a trustee of Callaway’s Choral Society and shared membership with Thorpe in the Chevy Chase and Metropolitan Clubs.“E. R. Finkenstaedt, Stockbroker, Dies,” Washington Post, August 5, 1979, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1979/08/05/e-r-finkenstaedt-stockbroker-dies/cb4aa4c4-6add-489c-8062-0c12dc39c5dd/?utm_term=.4f7b6c1c819c. “We feel it to be highly important to establish a local opera company in Washington as a living artistic entity,” said Finkenstaedt on the occasion of the society’s foundation.Hume, “Its Own Opera Company.”

Thorpe was the new company’s general manager, a position that he held until 1960, undertaking components of production as varied as staging, directing, and even translating, in addition to leveraging his social connections to fund the new cultural venture.Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 19. Callaway was the sole music director during the society’s first ten years, personally selecting the soloists and drawing on his previous collaborators in the National Symphony Orchestra and the Chamber Chorus of Washington to supplement the ensembles.Hume, “Opera Society Promising,” Washington Post, November 11, 1956, H11.

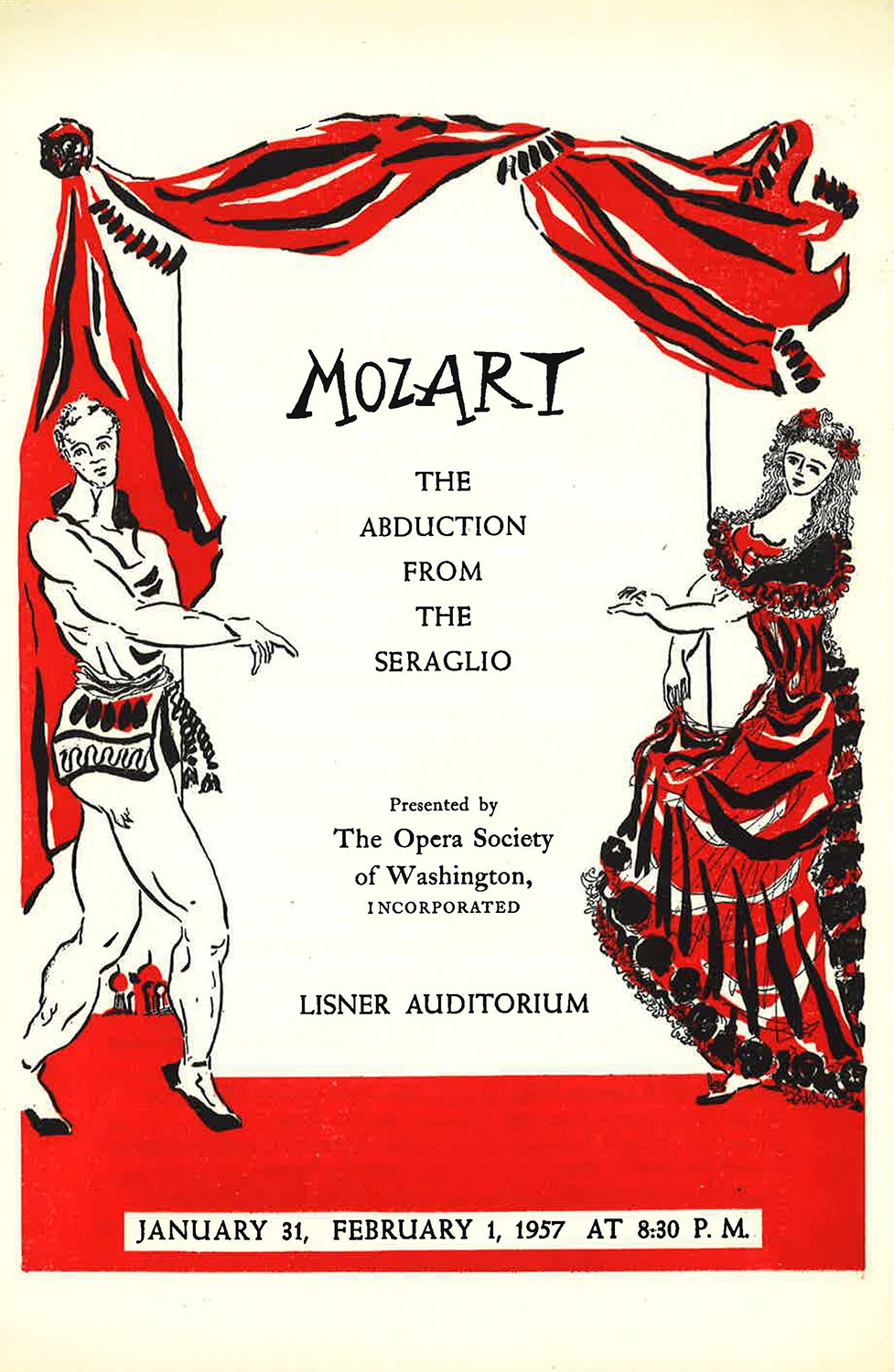

The company’s premiere production of Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) was staged at the request of the society’s first major benefactors, Gregory and Peggy Smith. Their support drew other Georgetown society to the company debut, including eleven ambassadors, the attorney general, and Marjorie Merriweather Post.Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 19. To distinguish the Opera Society’s caliber from the amateur companies that usually performed operas translated into English for easiest public consumption, Die Entführung was sung in the original German, although the spoken dialogue had been translated into English by Thorpe himself. The debut left the critic Paul Hume with “happy impressions . . . in terms of [the] future promise” of the enterprise.Paul Hume, “Reflections on a Premiere,” Washington Post and Times Herald, February 10, 1957, H10.

A double billing of Gian Carlo Menotti completed the society’s first season: a reprise of Callaway conducting The Unicorn, the Gorgon, and the Manticore with Menotti’s comic opera The Old Maid and the Thief. Ticket sales successfully recouped the Smiths’ initial $10,000 donation, and the bold, well-executed programming was an audacious pronouncement of the society’s intentions,Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 23. which as Thorpe put it, were “not [to] produce opera for an existing public” but to “try to create a new public whose enjoyment would be the Society’s sole, undivided interest.”Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 19.

The Opera Society of Washington rapidly became the capital’s operatic mainstay. It presented excerpts from Mozart’s Magic Flute for the Kennedys at the White House when they hosted Indira Gandhi in 1961 and staged and toured a production of Monteverdi’s Orfeo on period instruments in D.C. and Baltimore.Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 23, 27. The society’s connections also led to collaborations with leading musical figures. In the early 1960s, Igor Stravinsky conducted and recorded his Le Rossignol and Oedipus Rex with the company to rave reviews, and the society premiered and recorded Alberto Ginastera’s Bomarzo, which was deemed a “smash hit.”Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 27; Dorothy McCardle, “Opera Society Starts Drive for $100,000,” Washington Post and Times Herald, July 20, 1967, E1. Over the years, the society has hosted myriad other artistic stars early in their American careers, including Daniel Barenboim, Anna Netrebko, Franco Zeffirelli, and Samuel Barber.

Nevertheless, the Opera Society of Washington faced challenges, often due to conflicting artistic and financial interests. Board members, seeking a wider audience and larger financial base, programmed operas translated into English, which the musicians and critics alike decried as a debasement of the art and the society’s mission.Paul Hume, “Mozart’s Tongue Starts Snarls Over Operatic Control,” Washington Post and Times Herald, November 28, 1965, G7. Critics lamented that the production values were diminished by the cramped quarters of George Washington University’s Lisner Auditorium, where the society staged its productions for many years. Matters came to a head during the 1967 season, when the financial straits were so dire that the society remained dark for the season. This changed shortly after the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts opened in 1971, and the Opera Society became a tenant of its two-thousand-seat Opera House, a change that ushered in a period of dramatic growth for the company.Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 179–80.

More than a Provincial Opera Company

The society’s partnership with the Kennedy Center burgeoned in the 1970s, especially under the direction of George London (1920–1985) and Martin Feinstein (1921–2006). London, a retired bass-baritone, left his position as artistic administrator at the Kennedy Center for the Opera Society in 1976,John Rockwell, “Whither Opera (Locally Produced) in the Nation’s Capital?,” New York Times, November 28, 1976, 113. and one of his first acts was to change the name of the company to the Washington Opera, removing “the word ‘Society’ [which] reeked too much of the Precious Few.”“An Upbeat for Local Opera,” Washington Post, May 13, 1977, A20. Martin Feinstein took over in late 1979 and remained general director until 1995.Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 45. Feinstein, then executive director of the Kennedy Center and president of the National Symphony Orchestra, was already a powerful figure in the D.C. performing arts scene, and like Thorpe and Callaway before him, he used his status to the company’s benefit.Raymond Ericson, “Notes: Opera in Washington,” New York Times, June 15, 1980, D27.

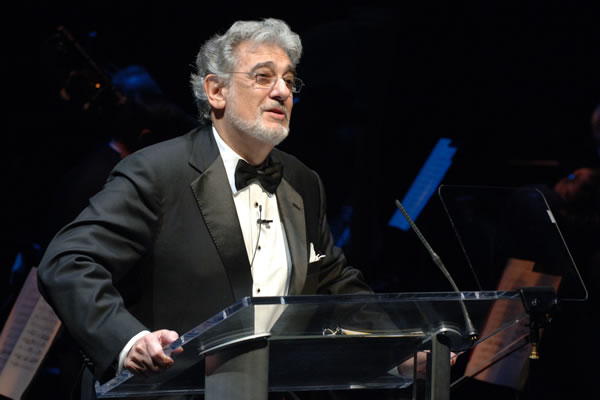

Perhaps the most important artistic event for the company during Feinstein’s tenure was tenor Plácido Domingo’s company debut in the world premiere of Menotti’s Goya in 1986.Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 47. After appearing in a few other productions, Domingo became a more permanent fixture in the company when he succeeded Feinstein as general director in 1996.Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 53. His inaugural performance in the lead role of Carlos Gomes’s Il Guarany, a little-known Brazilian opera, was attended by President and Mrs. Clinton and the president of Brazil and made Washington “the chic, the necessary, place to be” in the opera world.Tim Page, “Domingo’s Debut: A Capital Gain,” Washington Post, November 11, 1996, C1.

A National Opera Company for the Twenty-First Century

In 2004, Congress designated the company the Washington National Opera “to reflect the company’s solid reputation in the United States,” and in 2011, the Kennedy Center officially took over the Opera, securing its position on the capital’s cultural landscape.Phillips-Matz, Washington National Opera, 57. The designation and the oversight of the Kennedy Center has afforded the company national prominence that has enabled it to augment the company’s long-standing traditions. During Domingo’s tenure, the Washington National Opera introduced several educational and outreach initiatives, including the Domingo-Cafritz Young Artist Program, a resident-training program for artists on the verge of international careers, and summer camps to introduce opera to young musicians.“Domingo-Cafritz Young Artist Program,” Washington National Opera: The Kennedy Center, accessed July 18, 2018, http://www.kennedy-center.org/WNO/MTO/YAPProgram. The Washington National Opera also hosts open rehearsals that welcome local public schools and introduces opera to a broader audience through its popular Opera in the Outfield.“Opera in the Outfield,” Washington National Opera: The Kennedy Center, accessed July 18, 2018, https://www.kennedy-center.org/wno/simulcast. The American Opera Initiative, founded in 2012 “to stimulate, enrich, and ensure the future of contemporary American opera,” is reminiscent of Paul Callaway’s tradition of producing contemporary and sometimes avant-garde works.“American Opera Initiative,” Washington National Opera: The Kennedy Center, accessed July 18, 2018, https://www.kennedy-center.org/wno/mto/AOIInfo.

Profile by May Wang, 2018 summer intern