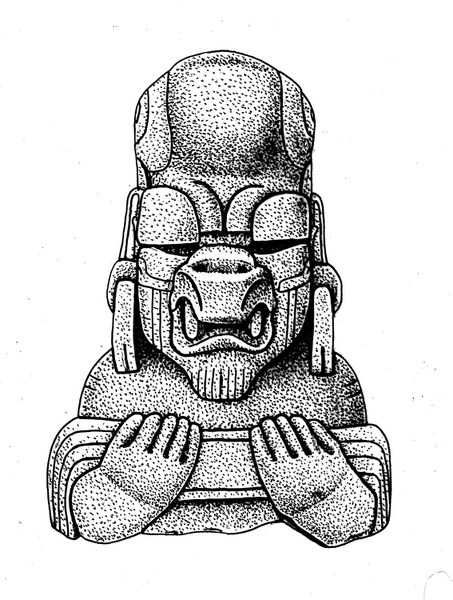

Transformation Figure in Combat Stance

| Accession number | PC.B.008 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 19 cm; W. 9.7 cm; D. 10.6 cm; Wt. 730 g |

| Technique and Material |

Serpentine |

| Acquisition history |

Reportedly found in Tabasco with PC.B.009; purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from Earl Stendahl, 1954 |

Despite its relatively small size, this statuette conveys an extraordinary amount of tension and power. This is achieved in part by the flexed and contorted position of the figure, whose tightly clenched hands evoke the powerful paws of the jaguar. In addition, the statuette exhibits a dense, compact body braced with thick and powerful musculature, with ropes of veins emanating from the forearms and lower abdomen. With his mouth partly open, the figure leans forward aggressively on his left leg. His right arm and shoulder are coiled in preparation to strike. In view of its pugilistic pose, George Kubler (1962:70) considers the figure a “middle-aged gladiator.” F. Kent Reilly (1989:14) also comments on the boxing stance. In fact, forms of boxing with conch shells, carved stones, and other objects are of considerable antiquity in Mesoamerica (see PC.B.016). In addition, in both ancient and contemporary forms of native Mesoamerican boxing, the jaguar frequently has a prominent symbolic role (Orr 1997, 2003; Taube 2018b; Taube and Zender 2009). A neatly drilled vertical hole passes through the right fist, indicating that the figure may once have wielded a weapon. This position of facing left while brandishing a weapon recalls a similar posture discussed by Peter T. Furst (1965:43–46) for the ceramic tomb art of Protoclassic West Mexico. According to Furst, left-facing West Mexican warrior figures depict shamans engaged in supernatural battle. In view of its obvious transformational theme, this Dumbarton Oaks sculpture probably represents an entranced shaman combating supernatural forces. The dynamic pose of this standing transformation figure is in strong contrast to the kneeling transformation figure (PC.B.603). Whereas the relatively static kneeling figure may represent the shaman in a posture preparatory to trance, this standing sculpture seems to depict a fully entranced individual engaged in shamanic battle. The physical form of the standing figure also suggests a more advanced altered state. Although the character still has human ears, cranium, and the tonsured coiffure typical of transformation figures, the smoothly projecting face is almost wholly jaguar, with a deeply furrowed brow, feline muzzle, and sharp canines. Moreover, the massive musculature behind the neck is typical of big cats, which use these muscles to tear or carry their prey. The narrow, steeply sloping shoulders and thick barrel chest also evoke the jaguar, as does the somewhat protruding belly and awkward knock-kneed stance. All these traits can also be observed on the even more feline transformation figure in combat stance (PC.B.009).

The style of the carving, form of the face, and type of serpentine are strikingly similar to a Middle Formative Olmec carving in the collection of the Princeton University Art Museum, which features another transformation with a similarly furrowed face and bald pate surrounded by hair at the sides and back of the head (1998-440). The treatment of the ears is also very similar, and this piece probably derived from the same workshop, if not the same artist, as both the piece under discussion and the third transformation figure at Dumbarton Oaks (see PC.B.009). As in the case of the aforementioned serpentine head at Dumbarton Oaks, this finely worked sculpture could well have been placed on a larger armature of wood or other material.

Carved of dark green, almost black, serpentine, the statuette gleams with a highly polished mirrorlike surface. Along with vestiges of root markings, particularly on the right brow, the sculpture has traces of cinnabar on the face, hands, and feet. The major region lacking high polish is the coiffure passing behind the ears, which was scraped horizontally with a coarse material to create a striated surface, evoking filaments of hair. In addition to the right hand, the eye orbits were also drilled, in this case to receive circular inlays of polished pyrite; only the proper left inlay remains. Smaller drills were employed to create shallow holes for the nostrils and spaces between the toes. The nails of the human hands and feet are delineated by fine line incision, as are the knuckles of the right hand. Designed to allow the sculpture to stand freely, the large and broad human feet are also carefully rendered to show ankle bones and high arches.

According to Samuel K. Lothrop (in Bliss 1957:234), this statuette and the other transformation figure in combat stance (PC.B.009) were found together in Tabasco. Both were stained with cinnabar, possibly at the time of burial. In view of their many stylistic similarities, Furst says “there seems little doubt that the two Bliss pieces came from the same master’s hand” (Furst 1968:150). He also notes that another highly polished transformation figure, now in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), is fashioned from a similar blackish-green serpentine with inlaid pyrite eyes, although the LACMA figure’s original pyrite inlays are only indicated by yellow staining (M.86.311.6). In addition, Furst (1968:150, fig. 2) calls attention to a similarly carved serpentine head from Huimanguillo, Tabasco. The brow on that example is marked by a pair of undulating bifurcated veins, virtually identical to the belly veins on this Dumbarton Oaks sculpture. The facial features of the Huimanguillo head are markedly similar to the head of another transformation figure evidently broken from a serpentine statuette (Princeton University Art Museum 1995:no. 47). Still another Olmec serpentine transformation figure was reportedly acquired by Teobert Maler at Dzibalchen, Campeche. It portrays a supine figure with a jaguar body and upward-gazing human head (see Metcalf and Flannery 1967). Although of varying form, it is quite possible that these serpentine figures were manufactured at a single workshop in the Tabasco area.

The transformation from human to jaguar is an important theme of portable greenstone sculpture among the Middle Formative Olmec. Although these figures tend to appear with different poses and in various degrees of transformation, they are frequently carved from similar stone, such as dark green serpentine. Along with the use of related stone, these figures often display shared stylistic conventions, suggesting they may have derived from a single locality within a relatively short period of time. The function of these figures remains largely unknown. The frequent use of green serpentine suggests they may relate to rituals concerning rain and agricultural fertility. I have suggested that transformation figures frequently concern shamanic rainmaking rituals (Taube 1995:100). In this regard, it is noteworthy that these sculptures frequently display the deeply furrowed brow and L-shaped eyes characteristic of the Olmec rain god, a being closely related to the jaguar. In addition, a finely carved serpentine image of the Olmec rain god (Figure 6.1) has the same coiffure and beard found with transformation figures, including this example under discussion and PC.B.009. Although there has been a great deal of academic interest in the role of shamans in curing, they have other important roles in traditional Mesoamerica, including serving as rainmakers, ritual practitioners known as graniceros in contemporary highland Mexico (see Albores and Broda 1997).

Notes

| Accession number | PC.B.008 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 19 cm; W. 9.7 cm; D. 10.6 cm; Wt. 730 g |

| Technique and Material |

Serpentine |

| Acquisition history |

Reportedly found in Tabasco with PC.B.009; purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from Earl Stendahl, 1954 |

Indigenous Art of the Americas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1956–1962

Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., June–October 1996

| Accession number | PC.B.008 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 19 cm; W. 9.7 cm; D. 10.6 cm; Wt. 730 g |

| Technique and Material |

Serpentine |

| Acquisition history |

Reportedly found in Tabasco with PC.B.009; purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from Earl Stendahl, 1954 |

Bliss, Robert Woods. 1957. Pre-Columbian Art: Robert Woods Bliss Collection. Text and critical analyses by Samuel K. Lothrop, William F. Foshag, and Joy Mahler. London: Phaidon. P. 234, no. 10, fig. 10, pl. 4.

Kubler, George. 1962. The Art and Architecture of Ancient America. Middlesex: Penguin Books. P. 70, pl. 35a.

Benson, Elizabeth P. 1963. Handbook of the Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. P. 5, no. 19.

Furst, Peter T. 1968. The Olmec Were-Jaguar Motif in the Light of Ethnographic Reality. In Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec, edited by Elizabeth P. Benson, pp. 143–174. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. P. 151, fig. 1.

Soustelle, Jacques. 1979. Les olmèques: La plus ancienne civilization du Mexique. Paris: Arthaud. Pl. 52.

Soustelle, Jacques. 1984. The Olmecs: The Oldest Civilization in Mexico. Translated by Helen R. Lane. New York: Doubleday. P. 129.

Reilly, F. Kent, III. 1989. The Shaman in Transformation Pose: A Study of the Theme of Rulership in Olmec Art. Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University 48(2):4–21. P. 14.

Saunders, Nicholas J. 1989. People of the Jaguar: The Living Spirit of Ancient America. London: Souvenir Press. Pp. 71–73.

González Calderón, O. L. 1991. The Jade Lords. Coatzacoalcos, Mexico: O. L. González Calderón. Pl. 228.

Princeton University Art Museum. 1995. The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership. Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum. P. 175, fig. 2.

Benson, Elizabeth P., and Beatriz de la Fuente, editors. 1996. Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. P. 229, no. 70.

Magni, Caterina. 2003. Les olmèques: Des origins au mythe. Paris: Seuil. Pl. 3-C.

Diehl, Richard A. 2004. The Olmecs: America’s First Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson. P. 107, fig. 69.

Taube, Karl A. 2004. Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. Pp. 62–64, pl. 6.

Gutiérrez, Gerardo, and Mary E. Pye. 2010. Iconography of the Nahual: Human-Animal Transformations in Preclassic Guerrero and Morelos. In The Place of Stone Monuments: Context, Use, and Meaning in Mesoamerica’s Preclassic Transition, edited by Julia Guernsey, John E. Clark, and Barbara Arroyo, pp. 27–54. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. P. 28, fig. 2.1.

Loisy, Jean de, and Sandra Adam-Couralet. 2012. Les maîtres du désordre. Paris: Musée du Quai Branly. P. 224, pl. 1.

| Accession number | PC.B.008 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 19 cm; W. 9.7 cm; D. 10.6 cm; Wt. 730 g |

| Technique and Material |

Serpentine |

| Acquisition history |

Reportedly found in Tabasco with PC.B.009; purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from Earl Stendahl, 1954 |