Fragmentary Figure

| Accession number | PC.B.585 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 7.6 cm; W. 5.1 cm; D. 3.8 cm; Wt. 171.31 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Acquired by Dumbarton Oaks from Edward Merrin, 1970 |

Carved from a fine, light blue mottled jadeite, this incised figure was probably broken from a standing statuette. The outstretched position of the lower arms is quite like other Olmec standing figures in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and, as has been noted, may indicate dance (see PC.B.014, PC.B.017, and PC.B.546). Although photographs in the printed catalogue make it seem that this piece was fashioned as part of a larger composite sculpture, with the lower portion perhaps made of perishable material, Juan Antonio Murro (personal communication, 2019) has recently inspected its lower portion and notes that it was indeed broken, with jagged edges and no indication of any attempt at grinding or smoothing the rough surface (see PC.B.018). That noted, this would have been a relatively large jadeite statuette, almost approaching in scale the intact standing male diopside jadeite statuette (PC.B.014).

In contrast to other Olmec jadeite figures at Dumbarton Oaks, there is relatively little attempt at subtle modeling and finishing. Instead, drilling, grinding, and saw marks are readily visible over much of the piece, endowing the figure with a rough but powerful quality. The drill holes for the nostrils and corners of the mouth are strikingly asymmetrical, which is curious considering both the very slow and deliberate process of creating them and the exceptional quality of the jadeite. Solid-core drills carved hollows in the upper arms, corners of the mouth, nostrils, and eyes—which were fashioned by three overlapping pits. The nasal septum is unpierced, but both earlobes are biconically drilled.

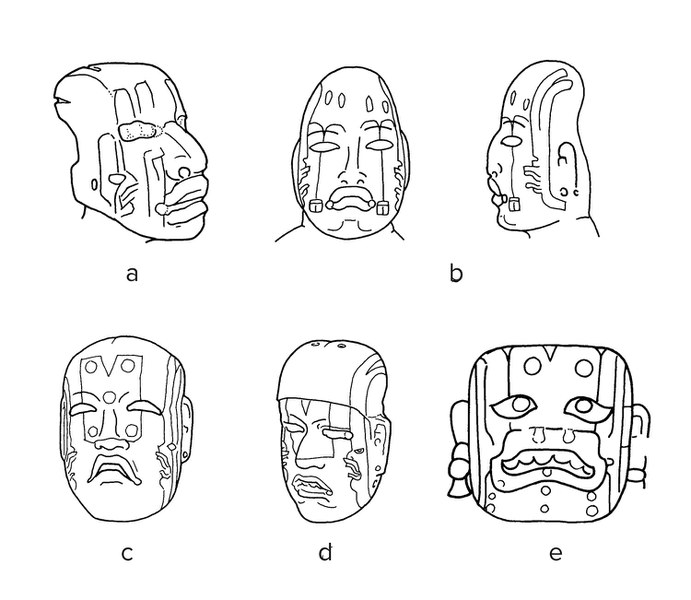

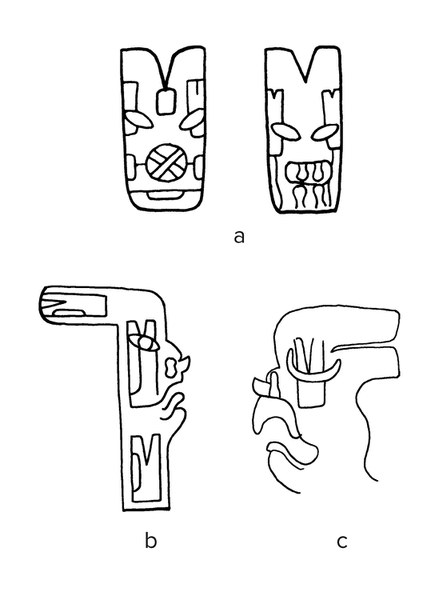

The fingers and, most notably, the face are carved with a fine line incision that delineates the upper teeth from the lip as well as two pairs of inward-looking profiles on each side of the face (Figure 15.3a). For these outer profile faces, the frontal half of each of the biconically drilled earlobes cleverly serves as eyes (Benson 1971:36). These rather schematic outer faces commonly appear on cleft-headed figures, which I regard as forms of the Olmec maize god (Taube 1996) (Figure 15.2a–b). Elizabeth P. Benson (1971:37) notes that such profile faces are also found on the jadeite Necaxa Statuette and on an incised celt from La Venta (Figure 15.2c–d). The La Venta example is an explicit representation of the Olmec maize god, complete with the banded maize sign growing out of its cleft head (Joralemon 1971:61). Moreover, with its prominent curling lip and eyes slanting up at the upper corners, the La Venta representation is very similar to the profile faces, as if these also constitute schematic forms of the Olmec maize god. Another jadeite celt, in this case attributed to Arroyo Pesquero, portrays the Olmec maize god flanked by a smaller profile face (Figure 15.2e). As personified forms of facial banding, these profile heads are also sometimes examples of God VI in the Peter David Joralemon (1971:79–81) system of deity classification (Figure 15.2f). Both the Necaxa Statuette and God VI have backward-sweeping crania, a trait I compare to young growing corn (Taube 1996). With their frequently cleft and back-turning crania, the flanking profile heads probably represent maize foliation, much as if the central face represents the ear of corn (see Figure 15.3d). As is noted later in this entry, PC.B.585 also portrays the personified aspect of green growing corn.

Two other larger profile faces appear in the region of the nose and eyes of the statuette (Figure 15.3a). In fact, as Benson (1971:36) notes, the statuette’s eyes double as the eyes of the profile faces, with their incised snouts lying against the sides of the sculpted nose. Below the snouts are pairs of parallel lines, with the outer lines running virtually to the chin of the statuette. Although these may well be the lower parts of the profile faces, they probably constitute mouth brackets for the statuette, a common convention for the Olmec maize god (see PC.B.592). The snouts of the larger profile faces are beak-like and recall the cleft-headed beaked faces on the shoulders of the Las Limas statuette (see Joralemon 1976:fig. 3b–c). The profile faces on PC.B.585 are also prominently cleft, a convention commonly referring to maize, foliation, and, by extension, greenstone celts. In the case of these two examples and the four cleft heads on the limbs of the Las Limas figure, the faces appear to be personifications of the foliated cleft celts on the limbs and faces of Olmec figures (see Figure 15.1; Feuchtwanger 1989:no. 104).

One incised figure displays facial markings quite similar to PC.B.585, including the inward-looking profile faces and prominent clefts over the eyes (Figure 15.3b). Its eye clefts, however, do not appear to connect to profile faces or celtiform motifs. In addition, although the cranium is back-curving, it is not nearly as developed as PC.B.585; it more closely resembles the cranial modification exhibited by the large standing jadeite statuette (PC.B.014) and the incised jadeite mask in Figure 15.3d. The facial markings on the mask are quite similar to those on an incised serpentine mask now in private hands (Figure 15.3c). This serpentine object is known to have been found at San Felipe, Tabasco (Sisson 1970). Still another example of this facial patterning occurs on an Olmec monument in the vicinity of Tenosique, on the lower central Usumacinta (Figure 15.3e). Although slightly eroded, the long, inward-facing profile heads are plainly visible, as is the cleft form in the center of the brow. Although PC.B.585 and Figure 14.3b have two cleft eye elements, the jade and serpentine incised masks and the Tenosique monument have only one central cleft device over the eyes.

The head of PC.B.585 appears to be a more developed, supernatural form of the slightly backward-curving cranium of the jade mask (Figure 15.3d), the other incised statuette (Figure 15.3b), and the standing jadeite figure (PC.B.014). On the fragmentary figure here, the head curves back at virtually a right angle to the face and does not terminate in a gently rounded bulge but with a hard, sharp edge. In addition, the back of the head has a deep cleft, much like a modern hammer claw. Combined with a lower pair of protuberances near the nape of the neck, the cleft cranium creates a four-part effect, as if the back of the head was transected by a cross. In profile, the cleft head is also represented by short horizontal incised lines at the end of the projecting cranium. In fact, a version of this same convention can be seen on the statuette in Figure 15.3b and the mask in Figure 15.3d, where the curving outer profile heads split apart near the back of the cranium. Occurring at the very edge of the face, the outer incised profiles of PC.B.585 may actually follow up along the side of the head to the back-curving cleft, thereby creating the same form as the latter two examples.

The earliest-known documented example of this deity is from the aforementioned hard stone incised celt (PC.B.016 and Figure 12.2a) (Hammond and Taube 2019). Holding the maize ear fetish, the figure has the same cleft cranium and profile deity heads found with PC.B.585. Since the incision is en face it could appear that the V-shaped cleft on the brow simply denotes a split forehead, but this is probably not the case, as when seen in profile or in the round the upper cranium turns sharply backward, like the aforementioned hammer claw.

The meaning of the sharply back-turning cleft cranium of PC.B.585 and other examples of this being requires further discussion. The Olmec maize god—complete with slanted eyes and five-part headband—can appear with this cranial form (Figure 15.4a–c). In one instance, the back-curving cleft seems to be supplied with a maize ear (Figure 15.4b). It is noteworthy, however, that the backward-turned cleft usually does not contain maize signs—quite probably because this convention represents the growing leafy plant rather than the mature ear of corn. The deity designated as God VI by Joralemon probably represents this aspect of green growing corn (Figure 15.4d–e). Because of the vertical line passing through the eye, Michael D. Coe (1968:111, 114) and Joralemon (1971:90) have identified the Olmec being as an early form of Xipe Totec, the Mexican flayed god of spring. Henry B. Nicholson (1976:165), however, notes that later Mesoamerican gods had similar facial banding, including Cinteotl, the Postclassic Central Mexican god of corn. Although Joralemon (1971:79) stresses that a line transecting the eye is an essential criterion for God VI, the vast majority of the cited examples derive from Early Formative Tlapacoya–style vessels. It is quite likely that the facial line for these early examples of this aspect of the maize god became the personified aspects of this same being seen on the cheeks of Middle Formative examples, including the Dumbarton Oaks figure (Figure 15.3). The vertical facial bands of the maize deity, the cleft, and the usually backward-curving cranium seem to be essential traits of this being, the foliated aspect of the Olmec maize god.

The backward-turning head transected in four parts is found on other examples of Olmec sculpture, including PC.B.592, the seated jadeite statuette from Arroyo Pesquero. As Benson (1971:17–19) and F. Kent Reilly (1994b:186) both note, a similar head form appears on the sculpture from San Martín Pajapan and on La Venta Monument 44 (see Figure 18.2a–b). On these two monuments, however, the back-curving element is not an actual cranium but part of a headdress, composed of long parallel lines identified as feathers by William Clewlow (1968:40). In view of their flexibility, narrowness, and length, these plumes surely represent the emerald-green tail feathers of the male quetzal, and in Olmec art quetzals are depicted with long and sharply curving tail plumes. The front of the San Martín Pajapan headdress displays the face of the Olmec maize god; a stylized world tree with a pair of radiating branches sprouts out of the cleft cranium (Figure 18.2a). The ends of these branches display the same four-sectioned form commonly appearing at the end of the back-curving cranium and headdress (Figure 18.1c). Both Reilly (1994a, 1994b) and I (Taube 1996, 2005, 2007, 2017a) have discussed the widespread use of maize as the axis mundi in Olmec iconography. It would appear that this fragmentary statuette and other figures displaying similar head forms represent the Olmec maize god in the specialized aspect of young growing maize, the Olmec form of the verdant world tree.

Notes

| Accession number | PC.B.585 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 7.6 cm; W. 5.1 cm; D. 3.8 cm; Wt. 171.31 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Acquired by Dumbarton Oaks from Edward Merrin, 1970 |

Lasting Impressions: Body Art in the Ancient Americas, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C., October 2011–March 2012

| Accession number | PC.B.585 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 7.6 cm; W. 5.1 cm; D. 3.8 cm; Wt. 171.31 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Acquired by Dumbarton Oaks from Edward Merrin, 1970 |

Benson, Elizabeth P. 1971. An Olmec Figure at Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. Pp. 36–37, figs. 44–46.

Niederberger, Christine. 1987. Paléopaysages et archéologie pré-urbaine du bassin de Mexico. 2 vols. Mexico City: Centre d’études mexicaines et centramericaines. Fig. 92.

Taube, Karl A. 2004. Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. Pp. 94–99, pl. 15.

| Accession number | PC.B.585 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 7.6 cm; W. 5.1 cm; D. 3.8 cm; Wt. 171.31 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Acquired by Dumbarton Oaks from Edward Merrin, 1970 |