Hummingbird Bloodletter

| Accession number | PC.B.025 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 6.7 cm; W. 2.2 cm; D. 1.6 cm; Wt. 18.5 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from Earl Stendahl, 1954 |

Fashioned from olive-green jade, this stylized hummingbird almost surely served as a bloodletting instrument. Although no explicit representation of penitential bloodletting is known in Olmec art, there is considerable archaeological evidence for bloodletting in Formative-period Mesoamerica. Among the jadeite bloodletters excavated at La Venta, one is in the form of a stingray spine, the bloodletting instrument par excellence in ancient Mesoamerica. Jadeite, obsidian, and actual stingray spine bloodletters are known from the highland site of Chalcatzingo, Morelos (Fash 1987:86–87; Grove 1987a:291; Thomson 1987:302); two of the obsidian bloodletters were serrated to imitate stingray spines (Grove 1987a:291). During the Middle Formative period at San José Mogote, Oaxaca, real stingray spines and serrated obsidian imitations were used in bloodletting rites (Marcus and Flannery 1994:62). Although jadeite bloodletters, including this hummingbird example, tend not to have very sharp points, they may have been used after an initial cut was made with obsidian or another sharp material—and some jade pieces may have been precious but nonfunctional votive copies of real lancets used in bloodletting.

Hummingbirds are an important Olmec bloodletting motif, with their long beaks serving as the piercing instrument. Several examples are known, in addition to the other piece at Dumbarton Oaks (PC.B.024). A virtually identical bloodletter of similar jade, complete with simple wings and boxlike body, was collected in the sixteenth century, quite probably as an Aztec heirloom (Roemer- und Pelizaeus-Museum Hildesheim 1986:pl. 342). Another hummingbird bloodletter was discovered in a cache of Olmec-style jades from Chacsinkin, Yucatan (Andrews 1986:fig. 9b). As in the case of this example, PC.B.025, and the Aztec heirloom, the Chacsinkin bloodletter was drilled for suspension. An Olmec hummingbird bloodletter was also found at Edzna, a Classic site of the northern Maya Lowlands (see Schmidt, de la Garza, and Nalda 1998:no. 238). On PC.B.025, the suspension hole doubles as the eyes of the bird. Jadeite perforators may have been worn by the Olmec elite; Monument 6 of Laguna de los Cerros portrays a figure wearing a pair of perforators as pendants on his chest (Fuente 1977a:illus. 76).

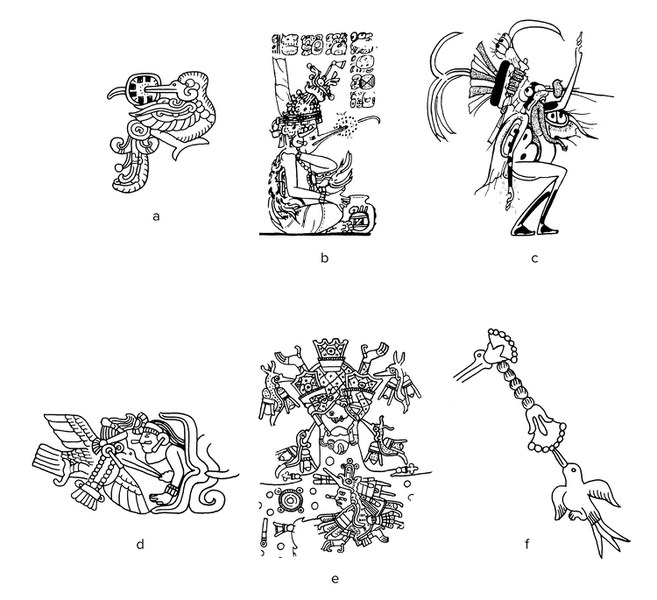

The identification of hummingbirds with sacrifice and bloodletting is relatively common in Mesoamerica. Despite their diminutive size, hummingbirds can be fiercely territorial, and they often attack creatures many times their size. Appropriately, the bellicose patron god of the Aztec was Huitzilopochtli, or “hummingbird on the left.” According to Aztec belief, the souls of slain warriors would return as hummingbirds and other winged creatures to drink the nectar of flowers (Sahagún 1950–1982:3:49). Unlike butterflies, however, hummingbirds do not simply sip flowers but also stab them with their long, pointed beaks. In Classic Maya art, the hummingbird generally appears with a flower transfixed by its long beak (Figure 19.1a–b). The same convention can be seen with mosquitoes, suggesting that these aggressive, buzzing bloodsuckers were considered to be the insect versions of hummingbirds (Figure 19.1c). Eduard Seler (1902–1923:4:576) calls attention to the widespread identification of hummingbirds with piercing and blood sacrifice in Mesoamerican thought. In a register from the Lower Temple of the Jaguar at Chichen Itza, hummingbirds pierce the chests of men emerging from flowers, as if the act of gathering nectar was tantamount to heart sacrifice (Figure 19.1d). Hummingbirds were also identified with blood and sacrifice in Late Postclassic Central Mexico. The Codex Borgia shows Quetzalcoatl in a hummingbird costume, standing below a flowering shower of blood. Directly above, four similarly winged figures attack a bat (Figure 19.1e). Three of the four winged creatures have antennae, suggesting they are mosquitoes. In Aztec iconography, hummingbirds frequently sip nectar from flowers blossoming from bone perforators (Figure 19.1f). The bone lancet and flower motif denote the blood as sweet nectar gathered by hummingbirds. Jadeite Olmec hummingbird bloodletters of similar form are known from other museum collections, including the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City (Figure 19.2) and the Princeton University Art Museum (2004-22; Figure 19.3).

Notes

| Accession number | PC.B.025 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 6.7 cm; W. 2.2 cm; D. 1.6 cm; Wt. 18.5 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from Earl Stendahl, 1954 |

Indigenous Art of the Americas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1960–1962

75 Years/75 Objects, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C., September 2015–May 2016

| Accession number | PC.B.025 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 6.7 cm; W. 2.2 cm; D. 1.6 cm; Wt. 18.5 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from Earl Stendahl, 1954 |

Bliss, Robert Woods. 1957. Pre-Columbian Art: Robert Woods Bliss Collection. Text and critical analyses by Samuel K. Lothrop, William F. Foshag, and Joy Mahler. London: Phaidon. P. 233, no. 7, pl. I.

Benson, Elizabeth P. 1963. Handbook of the Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. P. 8, no. 35.

Nicholson, Irene. 1967. Mexican and Central American Mythology. London: Hamlyn. P. 135.

González Calderón, O. L. 1991. The Jade Lords. Coatzacoalcos, Mexico: O. L. González Calderón. Pl. 466.

Taube, Karl A. 2004. Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. Pp. 122–124, pl. 19.

Baudez, Claude-Francois. 2012. La douleur redemptrice: L’autosacrifice precolombien. Paris: Riveneuve. Pp. 34–35, fig. 5.

| Accession number | PC.B.025 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 6.7 cm; W. 2.2 cm; D. 1.6 cm; Wt. 18.5 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from Earl Stendahl, 1954 |