Jade Mirror

| Accession number | PC.B.529 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 8 cm; W. 7.5 cm; D. 1.1 cm; Wt. 149.4 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Purchased from Frances Pratt, 1963; given to Dumbarton Oaks by Mildred Bliss |

Fashioned from mottled light blue-green jade, this plaque is rectangular with well-rounded corners. A pair of biconically drilled holes pierces the back upper edge of the piece, concealing suspension holes that are not visible from the front. The same technique is evident on the celtiform pendant in PC.B.023. The back of the plaque is slightly convex and bears two curving grooves running parallel to one of the vertical sides, probably aborted cuts made during the original blocking out and shaping of the piece. The front side has a gently concave and highly polished surface. In a detailed study of this object, John B. Carlson suggests it represents an effigy copy of an iron ore Olmec mirror, noting that the dimensions of the concave surface are virtually identical to those known for Olmec mirrors. Although Carlson interprets this item as a nonfunctional copy of an iron ore mirror, it is quite possible that, as with the metallic examples, this pectoral could have been used in divinatory scrying. In such divination, the play of light is at least as important as the quality of the reflection (Carlson 1993:249).

Although rare, other examples of Olmec jade mirrors do exist (Figure 28.1). The back of one concave jade mirror attributed to Guerrero bears an incised representation of a front-facing crested bird, quite possibly an owl or quetzal (Princeton University Art Museum 1995:no. 170). An incised jadeite disk marked with the image of the Olmec maize god may also have functioned as a mirror (see Benson and Joralemon 1980:no. 15).

The use of mirrors in divination is widely documented in Mesoamerica, and such mirrors often seem to have served as powerful emblems of high office (Carlson 1981). The ancient Maya deity God D, or Itzamna, an old god of priestly arts, commonly appears with a petaled mirror on his brow (Taube 1992b:31–34). Along with being a priest, this aged being is commonly enthroned, quite probably as the paramount god of the Maya pantheon (Taube 1992b:35–36, 146). The early colonial Yucatec Motul dictionary provides the following entry for u neen kab or u neen kah, signifying the mirror of the world or of the community: “el sacerdote, cacique, gobernador de la tierra o pueblo, que es espejo en que todos se miran” (the priest, chief, governor of the land or people, who is the mirror in which all see themselves) (Barrera Vásquez 1980:565). In that entry, the mirror is a metaphor for the priest or ruler, literally and figuratively reflecting the community. A number of ethnohistorical accounts describe the use of mirrors by Central Mexican rulers (Ekholm 1973). In Late Postclassic Central Mexico, the preeminent being of sorcery and magic was the omnipotent Tezcatlipoca, whose name means “smoking mirror.” In the early colonial Aztec chants recorded by Ruiz de Alarcón, the earth itself is described as the “mirror which gives off smoke” (Coe and Whittaker 1982:304, 308, 310).

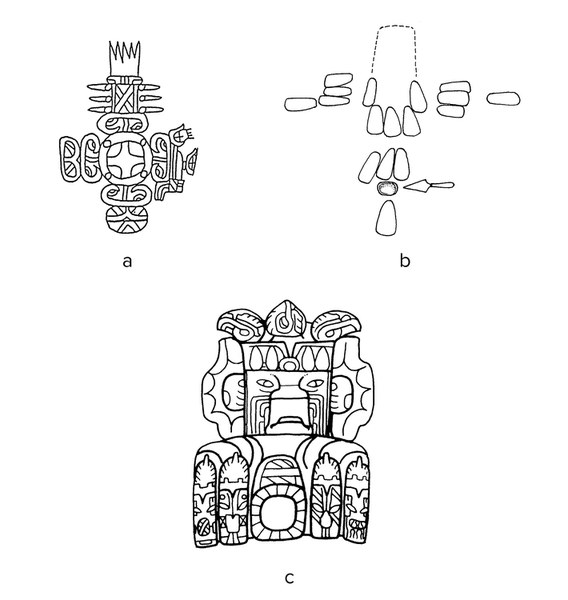

Just as rulers were commonly represented as embodiments of the pivotal world axis, mirrors were also identified with the world center in Olmec thought. The four-part motif on the Humboldt Celt has been interpreted as an Olmec representation of the four directions (Miller and Taube 1993:78; Reilly 1994b:129). It is quite possible that the circular element in the center of the four directional signs represents a mirror (Figure 28.2a). The La Venta cache known as Offering 1943-E contained a magnetite mirror within a cruciform placement of green celts (Figure 28.2b). Michael D. Coe (1972:9) interprets this arrangement as the world tree, with the mirror representing the “the quadripartite god who raised the world trees,” an early form of the four Tezcatlipocas who raise the heavens in Aztec myth. In the version of the story told in Historia de los mexicanos por sus pinturas, Tezcatlipoca transforms into a tree of mirrors (tezcacuahuitl), whereas Quetzalcoatl becomes the quetzalhuexotl willow (Garibay 1979:32). The allusion to a quetzal-willow is probably not coincidental; beginning in the Formative period, the quetzal and other precious green items are identified with the world center.

The four-celt headband commonly worn by the Olmec maize god often has a central circular device topped with maize as the world tree. The Arroyo Pesquero statuette (PC.B.592) has one of the most elaborate representations of this headband. On that figure, the central brow object is a petaled mirror topped with a vertical ear of corn (see Figures 18.1 and 28.2c). Placed in the center of the four-celt headdress, the vertical cob signifies the middle place, or axis mundi, also replicated by the capping image of the Olmec maize god as the world tree. Just as the Maya used the color green, or yax, for the middle place, the Olmec used such materials as green corn, jade, and quetzal plumes to depict the axis mundi. Thus, the Olmec maize god capping the Arroyo Pesquero statuette is probably a jade mask atop back-curving quetzal feathers, similar to the headdress masks and plumes on San Martín Pajapan Monument 1 and La Venta Monument 44 (Figure 18.2a–b). It also has been noted that the maize trefoil sign sprouting from the head of the Olmec maize god on the Arroyo Pesquero figure is marked with three quetzal heads (Figure 28.2c).

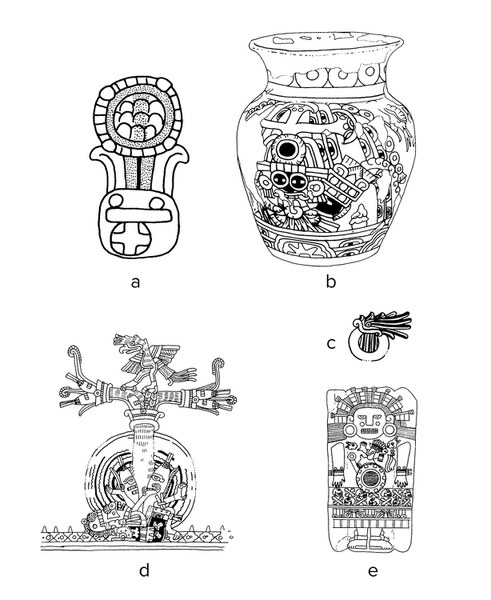

The concept of the mirror as the world center was widespread in ancient Mesoamerica. Along with wearing a mirror in the center of his brow, the Maya Itzamna also represents the world tree (Taube 1992b:36, 40)—like the earlier Olmec, the Maya used growing maize as a symbol of the world tree (Freidel, Schele, and Parker 1993:53–55). On one Early Classic censer portraying the Tikal king Great Jaguar Paw as the maize god, mirrors are used to represent ears of corn, both on his central headdress and on a plaque in his right hand (Figure 28.3a). It seems the yellow tesserae of the pyrite mirror are being compared to grains of corn. Among the Teotihuacanos and later cultures of Central Mexico, the middle place, known as tlalxicco or “earth navel,” was frequently represented as a large circular mirror held against the abdomen (Figure 28.3e) (Taube 1992a). A remarkable Early Classic vessel from Teotihuacan portrays Tlaloc wearing a petaled mirror on his forehead (Figure 28.3b). As in PC.B.592, a world tree rises above the central brow mirror. Along with spouting streams of water, this marvelous tree bears strings of green jade beads; a long-tailed quetzal, rendered in green and red, sits above the hanging jade. A very similar theme involving the central world tree appears on page 53 of the Late Postclassic Codex Borgia, which Eduard Seler (1963:atlas, 53) identifies as the tlalxicco (Figure 28.3c). The axis mundi is portrayed as a maize plant marked with jade signs rising out of a circular pool of water; a quetzal perches in the branches of this precious tree of abundance. The circular pool is surrounded by a yellow rim and likely alludes to a mirror. In Mesoamerican thought, mirrors are frequently compared to shining pools of water and, in fact, divinatory scrying was often performed with vessels of water (Taube 1992a:186, 189). On page 17 of the Codex Borgia, the diagnostic cranial mirror of Tezcatlipoca appears as a circular pool of blue water marked with the day name Atl, “water” (Figure 28.3d). Moreover, a greenstone sculpture excavated at the Aztec Templo Mayor portrays the central tlalxicco mirror as a pool of water (Figure 28.3e).

To the Olmec, mirrors fashioned of blue-green jade probably served as condensed symbols for the world axis. However, rather than referring simply to centrality, such mirrors also alluded to the overlapping themes of water, maize, and wealth. In contrast to Olmec hematite, ilmenite, and magnetite mirrors, which evoke the importance of these precious materials among the Early Formative Olmec, jade mirrors embody the Middle Formative concern with corn and related verdant items of wealth, these being jade and quetzal plumes. The relation of this complex of precious green items to mirrors and centrality did not end with the Olmec but continued in later traditions of ancient Mesoamerica. This jadeite mirror is a direct representation of the Olmec symbolism of jade which, like mirrors, is frequently related to the world center in Olmec thought.

Notes

| Accession number | PC.B.529 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 8 cm; W. 7.5 cm; D. 1.1 cm; Wt. 149.4 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Purchased from Frances Pratt, 1963; given to Dumbarton Oaks by Mildred Bliss |

Benson, Elizabeth P. 1963. Handbook of the Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. P. 9, no. 40.

González Calderón, O. L. 1991. The Jade Lords. Coatzacoalcos, Mexico: O. L. González Calderón. Pl. 483.

Carlson, John B. 1993. The Jade Mirror: An Olmec Concave Jadeite Pendant. In Precolumbian Jade: New Geological and Cultural Interpretations, edited by Frederick W. Lange, pp. 242–250. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. Fig. 18.1.

Taube, Karl A. 2004. Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. Pp. 141–145, pl. 28.

| Accession number | PC.B.529 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 8 cm; W. 7.5 cm; D. 1.1 cm; Wt. 149.4 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Purchased from Frances Pratt, 1963; given to Dumbarton Oaks by Mildred Bliss |