Duck-Billed Pendant

| Accession number | PC.B.022 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 8.3 cm; W. 3.5 cm; D. 1.6 cm; Wt. 52.9 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Formerly in the collection of Joseph Brummer; purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from V. G. Simkhovitch, 1948 |

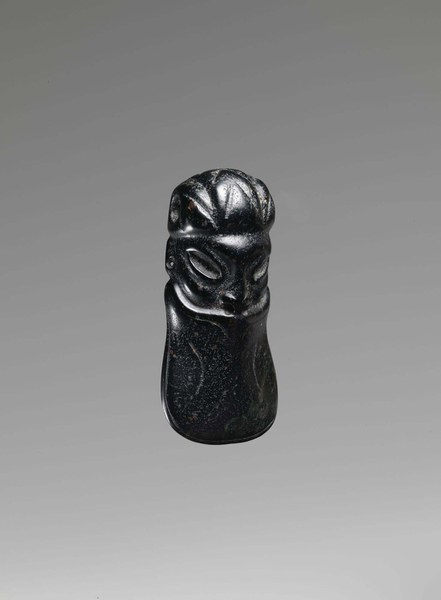

Fashioned from translucent, mottled blue-green jade, this finely worked pendant was first published in 1943 (Kelemen 1943:pl. 237c), when it was owned by the Brummer Gallery of New York. It portrays an otherwise human head supplied with a massive duck bill. Although the face appears to have considerable depth, it is actually quite shallow, cut from the same planar surface as the broad bill. Both the septum and earlobes are pierced, and it is possible that small pendants once hung from the ear holes. Rather than being an obvious mask, the duck bill curves organically with the contours of the lower cheeks and connects directly to the nasal septum; it is incised with bold fluid lines, with the vertical crescent elements representing nostrils. The curling form at the top of the piece, probably braided hair, is considerably thicker than the face and bill. A laterally drilled hole passing through the sides of this section provides the means of suspension. Complex in form, the coiffure or headdress is slightly cleft in the lower center, mirroring the curving edge and pointed center of the beak. The cleft is in a central area marked with inverted V-shaped incisions, evidently denoting braiding. At the back of the head, this element ends with a straight, rather than cleft, edge. Similarly marked elements curl at the sides of this central section, effectively spiraling around the laterally drilled suspension hole.

Precious stone pendants with broad duck bills were notably popular and widespread in ancient Mesoamerica. This may be partly because of the broad thin bill, which allows light to pass through translucent stone. Elizabeth Kennedy Easby and John F. Scott (1970:48–50) illustrate three Olmec duck-head pendants carved in brilliant emerald-green jade. A similar jadeite duck-head pendant was found during 1942 excavations at La Venta (Drucker 1952:pl. 54). A jadeite duck-head pendant was discovered in a Middle Formative burial from Mound 20 at San Isidro, Chiapas (Lowe 1981:fig. 7g). At Kaminaljuyu, a duck-head pendant and other jade pendants and beads of late Olmec style were discovered in a Late Formative cache in association with the burial of Kaminaljuyu Stela 9, a monument probably dating to the Middle Formative period (Parsons 1986:16, fig. 6). At least one jade duck-head pendant was discovered in a Middle Formative burial at Playa de los Muertos, Honduras (Healy 1992:fig. 7).

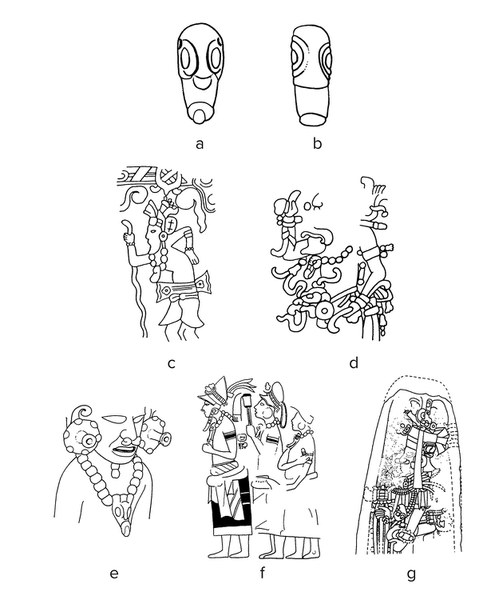

Pendants in the form of duck heads are also known from a number of Classic Maya sites, including Kaminaljuyu, Uaxactun, Nebaj, Altun Ha, and Dzibilchaltun, where they have generally been misidentified as alligator heads (Figure 36.1a–b) (Kidder 1947:fig. 34c; Kidder, Jennings, and Shook 1946:fig. 148b; Pendergast 1990:264, fig. 120a; Smith and Kidder 1951:57e, 62d; Taschek 1994:fig. 11b–e). In addition, representations of duck-head pendants are relatively common in Protoclassic and Early Classic Maya art and can be seen at Kaminaljuyu, Uaxactun, and Tikal (Figure 36.1c–g). These duck-head jewels are typically the central pendant on a necklace of large beads. An Early Classic mural from Uaxactun portrays no fewer than three individuals wearing duck-head necklaces (Figure 36.1f). Although this jewelry is poorly documented for the Late Classic period, the Aztec fashioned duck-head pendants in translucent amethyst and obsidian during the Late Postclassic period (Easby and Scott 1970:nos. 301–302; Feest 1990:fig. 19). Obsidian examples in various stages of manufacture were excavated at Late Postclassic Otumba, Mexico (Otis Charlton 1993:239–240, fig. 10g–i).

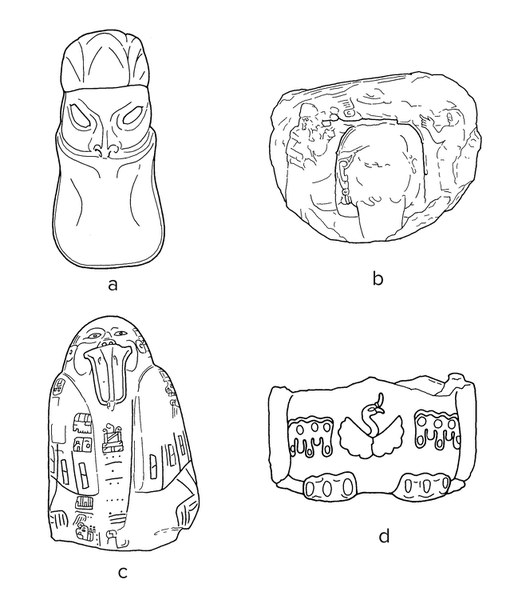

PC.B.022 differs from these cited duck-head pendants in one significant way: rather than simply representing a duck, the pendant depicts a human face with a duck bill. A similar fusion of human and duck can be found on an Early Formative effigy vessel representing a duck with human ears (Princeton University Art Museum 1995:no. 58). Indeed, a still earlier merging of duck and human can be seen with a Mokaya-phase tecomate ceramic sherd dating to roughly 1400 BCE, from the south coast of Chiapas. But there is a virtually identical piece to PC.B.022 in the collection of the Princeton University Art Museum—an Olmec pendant carved in hard black stone (Figure 36.3). Along with the face and large bill, the black pendant also displays the same coiffure or headdress. La Venta Altar 7 portrays another Middle Formative example of this character, in that case in an altar niche (Figure 36.2b). Both La Venta Altar 7 and PC.B.022 have been compared to the famous Tuxtla Statuette at the National Museum of Natural History, which portrays a bald-headed man with a duck body and bill (A222579-0; Bliss 1957:233; Drucker 1952:183; Kelemen 1943:291). Like the Middle Formative examples, the bill projects down below the nose as an integral part of the face (Figure 36.2c). Although the Tuxtla Statuette does appear to represent a related entity, it bears a Long Count date corresponding to 162 CE, well after the Middle Formative Olmec.

An anthropomorphic duck deity is also well documented for the ancient Maya, including a large jade pendant in the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología in Guatemala City, which features a being with a human nose and nostrils but also a prominent broad duck bill (Figure 36.4). Another Maya pendant of this being in deep emerald-green jade was found at Hatzcab Ceel, Belize (see Taube et al. 2010:fig. 32). But one of the most important discoveries pertaining to this being among the ancient Maya is from the Late Preclassic West Wall mural at San Bartolo, Guatemala, where he sings and dances accompanied by chirping birds below roiling rain clouds (Taube et al. 2010:fig. 32). A prominent date next to him, 3 ik’, pertains directly to his nature, with ik’ being the Maya term for wind and this deity constituting an avian wind god.

Until the discovery of San Bartolo, there was little evidence of a duck-billed wind deity among early cultures of Mesoamerica, although David Stuart (personal communication, 1993) first noted that a duck-billed character is epigraphically labeled ik’ k’u, or “wind god,” on a carved step from Yaxchilan Structure 33. Stuart also noted that in the scene of water beings from Bonampak Room 1, a duck-billed figure has the ik’ wind sign in his eye. Confirmation is provided by a Late Classic duck-billed figure displaying ik’ signs on his body. Along with an augury indicating abundance, the Dresden Codex (page 44c) features a Postclassic form of the ik’-eyed duck god fishing with Chaak, the Maya god of rain.

In Late Postclassic highland Mexico, there was one major deity known for his duck-billed mask: Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl, also the god of wind. According to Scott O’Mack (1991), this bucal mask is based on the ecatototl, or “wind bird,” the hooded merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus). One particular species of duck, the atapalcatl (Oxyura jamaicensis), was believed to be a harbinger of rain: “It is named atapalcatl because if it is to rain on the next day, in the evening it begins, and all night [continues], to beat the water [with its wings]. Thus the water folk know that it will rain much when dawn breaks” (Sahagún 1950–1982:2:36). Similarly, it was Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl who brought the fertile rain clouds: “Quetzalcoatl—he was the wind; he was the guide, the roadsweeper of the rain gods” (Sahagún 1950–1982:1:9). The act of fishing, or raising fish into the sky, seems to have been regarded as a symbolic rainmaking act (Taube 1995:95n53). Nikolai Grube notes that the Classic Maya glyph of conjuring gods and ancestors, the “fish in hand” sign, is read as tsak, a Maya term signifying the conjuring of clouds as well as fishing (Freidel, Schele, and Parker 1993:436n650).

The Maya duck-billed deity shares other, secondary attributes with Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl. In one Late Classic vessel scene, the Maya god wears a spoked shell pectoral very much like the cut conch “wind jewel” pectoral of the Aztec wind god. Seibal Stela 3 portrays the duck deity as a musician shaking a rattle, and in Late Postclassic Central Mexico, the wind god is also a maker and bringer of music. A passage of the Codex Borgia (pages 36–38) pertaining to the mythic origins of music portrays instruments and articles of music and dance carried in a great spiraling wind stream personified as Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl. This concept of the duck-billed wind god as a god of music can be traced to the Late Preclassic murals at San Bartolo, Guatemala (Taube et al. 2010:48–49). In the West Wall mural of Structure Sub-1A of the Pinturas Group from this site, he appears enthusiastically dancing and singing along with chirping birds. A still more remarkable concept is that this duck-billed being appears in the initial phases of the Early Formative in Mesoamerica.

Like the later cultures of Late Postclassic highland Mexico, the Classic Maya considered an anthropomorphized duck-billed being as a god of wind, and here with wizened, wrinkled features. Although it is difficult to relate the Olmec being directly to wind, ducks, by their natural habitat, obviously pertain to water. I previously suggested Early Formative duck effigy vessels with beak spouts may allude to ducks as water bringers. For the aforementioned duck censer, the smoke clouds rise out of the beak, as if the breath of this being is the cloud bringing wind. San Lorenzo Monument 9 provides a still more compelling case; originally part of the elaborate Early Formative system of drains and pools at San Lorenzo, the monument portrays a great web-footed duck (Coe and Diehl 1980:1:314). Another duck rendered in bas-relief appears on its chest. Flanked by probable rain clouds, the great bird appears to be beating its wings, quite like the Aztec description of the atapalcatl duck. As among later peoples of ancient Mesoamerica, the Olmec identified the duck with rain, water, and fructifying powers of agricultural fertility.

Notes

| Accession number | PC.B.022 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 8.3 cm; W. 3.5 cm; D. 1.6 cm; Wt. 52.9 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Formerly in the collection of Joseph Brummer; purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from V. G. Simkhovitch, 1948 |

Indigenous Art of the Americas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1952–1962

| Accession number | PC.B.022 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 8.3 cm; W. 3.5 cm; D. 1.6 cm; Wt. 52.9 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Formerly in the collection of Joseph Brummer; purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from V. G. Simkhovitch, 1948 |

Kelemen, Pál. 1943. Medieval American Art. 2 vols. New York: Macmillan. P. 291, pl. 237c.

Bliss, Robert Woods. 1957. Pre-Columbian Art: Robert Woods Bliss Collection. Text and critical analyses by Samuel K. Lothrop, William F. Foshag, and Joy Mahler. London: Phaidon. P. 233, no. 3, pl. I.

Benson, Elizabeth P. 1963. Handbook of the Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. Pp. 7–8, no. 33.

Coe, Michael D. 1965. The Olmec Style and Its Distribution. In Archaeology of Southern Mesoamerica, edited by Gordon R. Willey, pp. 739–775. Vol. 3 of Handbook of Middle American Indians, edited by Robert Wauchope. Austin: University of Texas Press. P. 751, fig. 25.

Benson, Elizabeth P., and Beatriz de la Fuente, editors. 1996. Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. P. 130, fig. 11.

Taube, Karl A. 2004. Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. Pp. 169–173, pl. 36.

| Accession number | PC.B.022 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Middle Formative,

900–300 BCE

|

| Measurements |

H. 8.3 cm; W. 3.5 cm; D. 1.6 cm; Wt. 52.9 g |

| Technique and Material |

Jadeite |

| Acquisition history |

Formerly in the collection of Joseph Brummer; purchased by Robert Woods Bliss from V. G. Simkhovitch, 1948 |