Around 1743, while in pursuit of plants, John Bartram (1699–1777) described his encounter with a rattlesnake:

After dinner we passed the openings of two ridges, the last of which was by the bank of the principal branch of Swataro, the soil poor and stoney; then we ascended a great ridge about a mile steep, and terribly stoney, most of the way: near the top is a fine tho’ small spring of good water. At this place we were warned by a well known alarm to keep our distance from an enraged rattle snake that had put himself into a coiled posture of defence, within a dozen yards of our path, but we punished his rage by striking him dead on the spot: he had been highly irritated by an Indian dog that barked eagerly at him, but was cunning enough to keep out of his reach, or nimble enough to avoid the snake when he sprung at him. We took notice that while provoked, he contracted the muscles of his scales so as to appear very bright and shining, but after the mortal stroke, his splendor became much diminished, this is likewise the case of many of our snakes.

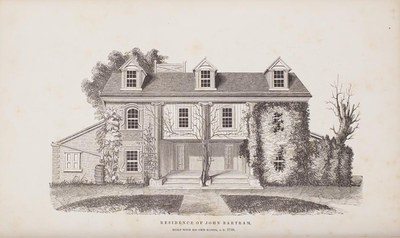

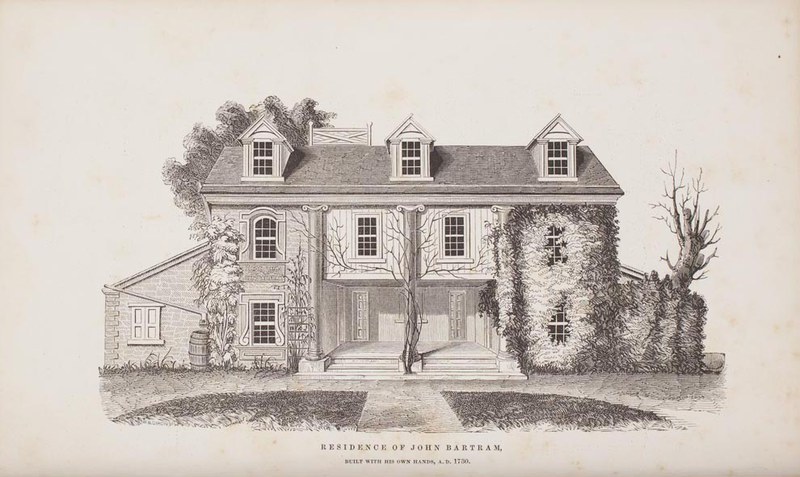

Called the greatest natural botanist

by Carl Linnaeus, John Bartram was the founder of a botanical garden near Philadelphia in which he grew native plants and specimens from abroad, and which served as a base for his botanical explorations. A third-generation Philadelphia Quaker with no advanced education, Bartram carried on a transatlantic botanical exchange with another Quaker, the English merchant-botanist Peter Collinson (1693–1768). Between 1730 and 1768, Bartram and Collinson maintained extensive correspondence on plants, classification, gardens, and even their personal lives, exchanging and demanding unique regional specimens and descriptions in their letters. Both men requested specific plant samples and did their best to collect or acquire such specimens, but it was a challenging endeavor. Collinson wrote to Bartram on February 20, 1735:

I have procured from my knowing friend, Phillip Miller, gardener to the Physic Garden at Chelsea, belonging to the Company of Apothecaries, sixty-nine sorts of curious seeds, and some other of my own collecting [for you]. This, I hope, will convince thee I do what I can; and if I lived, as thou does, always in the country, I shall do more; but my situation it is impossible. Besides, most of the plants thou writes for, are not to be found in gardens, but grow spontaneously a many miles off, and a many miles from one another.

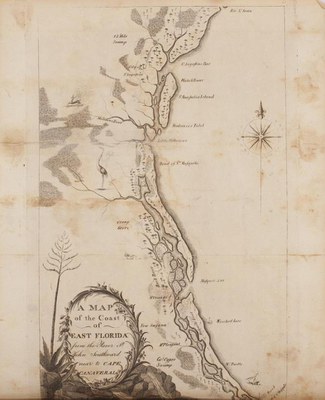

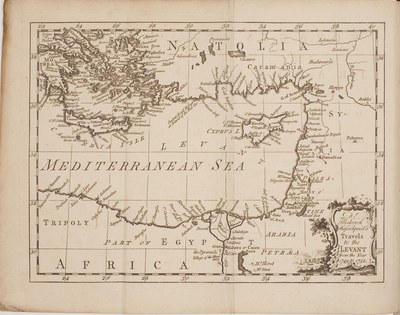

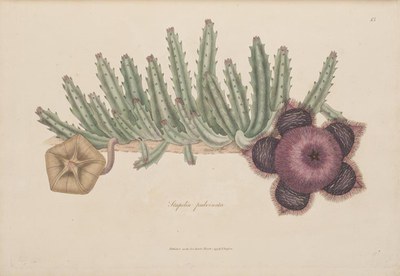

Bartram, Collinson, and other naturalists exchanged letters, living plants, herbarium specimens, and illustrations. Bartram added to and shared botanical specimens from his garden, which is considered the first true botanical garden in America, where he grew useful, unusual, and native plants, some never before having been cultivated in a garden. Acquiring such items demanded extensive networks of contacts as well as extensive fieldwork. In 1743, Bartram collected botanical specimens in travels from Pennsylvania to Ontario. In 1761, he brought his son, William Bartram, with him on a collecting trip to the Appalachians and Carolinas, and in 1765 and 1766, he traveled through the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida (territories his son also botanized in the 1770s). The hardships were well worth the effort, however, as long-lasting, long-distance professional relationships were built on such botanical exchanges. On February 18, 1756, Philip Miller (1691–1771) wrote to Bartram:

As you desire to know my wants, that you may supply them, I must desire you will acquaint me with what things you want from hence, that I may make you some returns; and although in my other letter I pretty fully told what would be acceptable, yet have I here sent you a list of some things taken out of the Flora Virginica, which book I suppose you have, so will soon know what I mean by the names. . . . I shall take every opportunity to write to you, and shall always be glad to hear from you, being your obliged friend and servant.

The transatlantic network fostered by Bartram and Collinson created a web of botanical connections. Despite the distance, and thanks in part to his association with Collinson, Bartram seems to have corresponded with or met many important botanical figures of this long era: Linnaeus, Barton, Sloane, Mitchell, Dillenius, Clayton, Kalm, Fothergill, Garden, Gronovius, Gordon, and Thomas Jefferson. In 1743, with Benjamin Franklin, he co-founded the American Philosophical Society.

Bibliography

- Bartram, John. Observations on the inhabitants, climate, soil, rivers, productions, animals, and other matters worthy of notice made by Mr. John Bartram in his travels from Pensilvania to Onondago, Oswego, and the Lake Ontario in Canada. London: Printed for J. Whiston and B. White, 1751.

- Cheston, Emily R. John Bartram, 1699-1777: His Garden and His House; William Bartram, 1739–1823. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: John Bartram Association, 1953.

- Darlington, William. Memorials of John Bartram and Humphry Marshall: With Notes of their Botanical Contemporaries. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1849.

- Petersen, Ronald H. New World Botany: Columbus to Darwin. Ruggell [Liechtenstein]: A. R. G. Gantner Verlag, 2001