In the 1790s, Joseph Banks wrote to King George III about one of His Majesty’s botanical subjects, whom he credited with collecting and sending home a profusion of plants unknown . . . to the Botanical Gardens of Europe, a full account of which will appear in Mr Aiton’s catalogue of plants in the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew . . . by means of these Kew Gardens has, in great measure, attained to that acknowledged superiority it now holds over every other establishment in Europe, some of which, the Trianon, Paris, Upsala, till lately vied with each other for pre-eminence without admitting even comparison from any English garden.

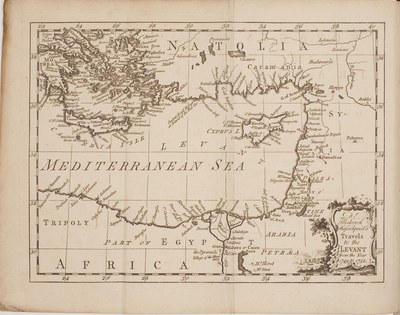

He added that this individual’s work at the Cape of Good Hope yielded a far larger number of plants than the famous journey to the Levant made by M. Tournefort by the order of Louis XIV at an immense expense.

Banks was writing of Francis Masson (1741–1805), a Scottish gardener and Kew Garden’s first official plant hunter. In June of 1772, Masson set sail on the first of two trips to the Cape. In total, he would spend twelve years in South Africa. A record of Masson’s journeys on his first trip was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1776 as An Account of Three Journeys from the Cape Town into the Southern Parts of Africa; undertaken for the Discovery of new Plants, towards the Improvements of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew. This provided the first fully detailed print description of the plants of the southern and southwestern Cape. This area, currently known as the Cape Floral Kingdom, is the smallest but richest of the world’s floral kingdoms. Masson’s role in bringing some of this wealth of plants back to the English gardens was as immense as his physical suffering in the task.

The terrain of the Cape was challenging, ranging from steep mountains and gullies to parching deserts and stormy coastlines. In 1773, while botanizing in the mountains near the River Zonderend, Masson described the struggles of the day and his conflicting emotions:

climbed many dreadful precipices until we arrived at the dark and gloomy woods with trees 80 to 100 feet high interspersed with climbing shrubs of various kinds. Trees were often growing out of perpendicular rock and among these the water sometimes fell in cascades over rock 200 feet perpendicular with an awful noise . . . I endured the day with much fatigue, and the sequestered and unfrequented woods, with a mixture of horror and admiration.

These extreme experiences marked many of his days at the Cape. On one occasion his traveling companion nearly died after falling into a submerged hippopotamus pit.

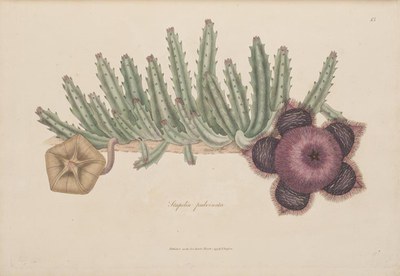

The large collections of living plants and seeds sent back from the Cape by Masson set off a craze for Cape flowers in England at the end of the eighteenth century. Nearly one-third of the 786 plates of flowering plants in the first 20 volumes of William Curtis’s Botanical Magazine were introduced through Masson’s efforts. These plates represent a wealth of proteas, gladioli, calendulas, xeranthemums, hibiscuses, ericas, tritonias, lobelias, amaryllises, gardenias, pelargoniums, stapelias, and massonias. A contemporary of Masson, Sir J. E. Smith wrote of the “novel sight of African geraniums in York or Norfolk soon after Masson’s death. Now every garret and cottage window is filled with numerous species of the beautiful tribe and every greenhouse glows with the innumerable bulbous plants and splendid heaths of the Cape. For all these we are principally indebted to Mr. Masson, besides a multitude of rarities.”

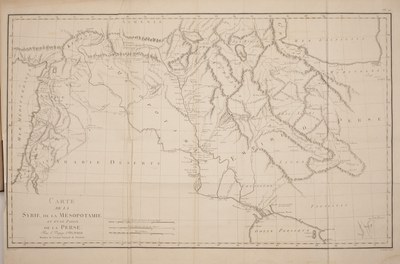

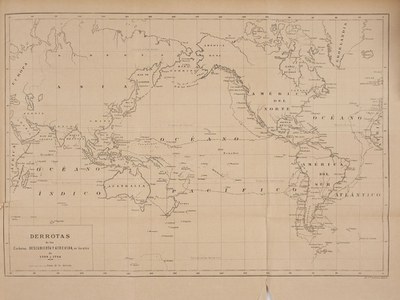

After exploring the Cape and working quietly at Kew for several years, Masson returned to plant hunting. In the late 1770s, he traveled to Madeira, the Canaries, the Azores, and Teneriffe before moving on to the West Indies. In the early 1780s, Masson sent back plants from Portugal, Spain, and finally North Africa. He endured numerous difficulties, including being caught in the crosshairs of a battle, a hurricane that destroyed all of his specimens, and raids by privateers. He began the winter of 1805 in Montreal, where he succumbed to the extreme cold of the Canadian winter at the age of sixty-five. By the end of his life, Masson had managed to introduce more than a thousand species of plants to Britain.

Bibliography

- Fraser, Mike, and Liz Fraser. The Smallest Kingdom: Plants and Plant Collectors at the Cape of Good Hope. Richmond, Surrey: Kew, 2011.

- Lemmon, Kenneth. The Golden Age of Plant Hunters. 1st American ed. South Brunswick, NY: A. S. Barnes, 1969.