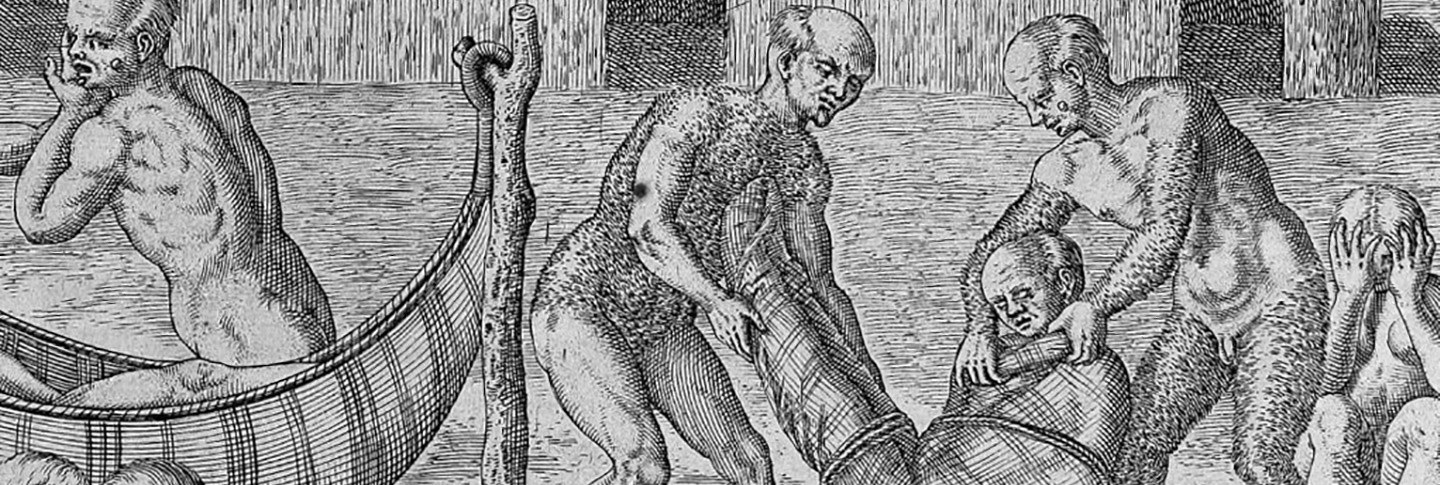

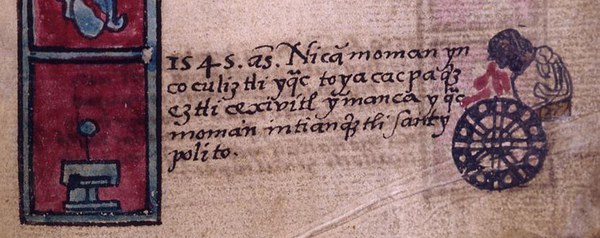

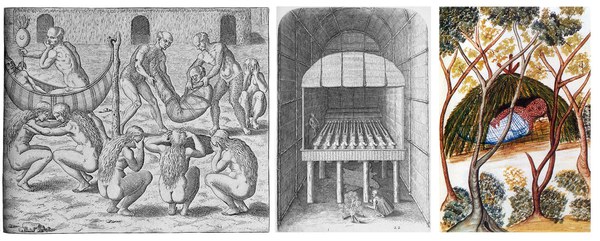

Nahua medicine, despite all its advances, was unfit to combat the abrupt appearance of foreign germs. In the left image, a Nahua medic diagnoses two patients covered in red rashes, likely typhus victims, an illness that killed 150,000 people in Tlaxcala in 1545 alone. In the right image, glyphs representing screams of pain emanate from the mouth of an Indigenous male patient hospitalized at the Royal Hospital for Indians in Mexico City.

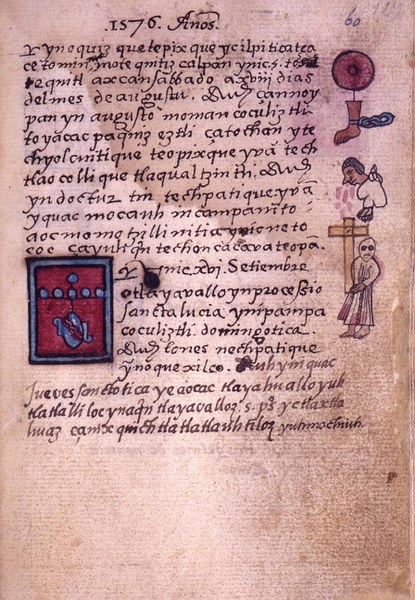

Dozens of epidemics ravaged Mesoamerica during the sixteenth century. In addition to the 1520 smallpox outbreak that led to the fall of Tenochtitlan, two exceptionally deadly outbreaks of cocoliztli, a hemorrhagic fever, occurred in 1545 and 1576, accompanied by other widespread outbreaks of mumps, measles, influenza, typhus, meningitis, smallpox, dysentery, whooping cough, and pneumonic plague. The aggregated impact of these successive illnesses led to the collapse of agricultural production and distribution networks, which aggravated droughts and increased mortality. Famine was common. In the words of Toribio de Benavente “Motolinia,” many “died of starvation, because, as they were all taken sick at once, they could not care for each other, nor was there anyone to give them bread or anything else.” (Motolinia 1950:38).

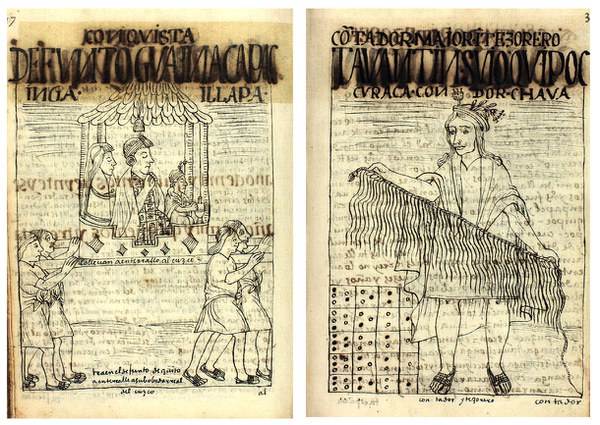

Pathogens spread swiftly across the hemisphere, leaping ahead of the Europeans through contact between neighboring communities. Years before the Spaniards arrived in the Andes, the Inca Empire experienced an outbreak of smallpox that decimated the royal family, paving the way for the Spanish invasion. In 1539, pestilence and famine were said to take the lives of one hundred thousand people in Popayán; Bogotá lost forty thousand Natives to smallpox in 1558 alone; nearly all Native people in Cuenca were ill with smallpox by 1562; and Lima witnessed a population decline of 20 percent in 1586 in an outbreak that claimed the lives of Natives and enslaved African descendants. Countless other communities were decimated by European germs, resulting in the decline of approximately 90 percent of the Indigenous population of the Americas by century’s end. Epidemics were exacerbated by the conditions that Europeans imposed on their colonies. Pathogens thrived as much and as long as they did because of the exploitative labor, unsanitary living, and urban confinement that colonists forced onto their subjects.

Image Sources

- Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, MS Magliabechiano XIII.3 (Codex Magliabechiano), fol. 78r. By permission of the Ministry of Culture / Central Library, Florence.

- Pintura del gobernador, alcaldes y regidores de México. Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, ca. 1565, fol. 6v. Courtesy of the collections of the Biblioteca Nacional de España.

Further Reading

- Cook, Noble David. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. New Approaches to the Americas. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Motolinia, Toribio de Benavente. Motolinía’s History of the Indians of New Spain. Edited and translated by Elizabet Andros Foster. Berkeley: The Cortés Society, 1950.