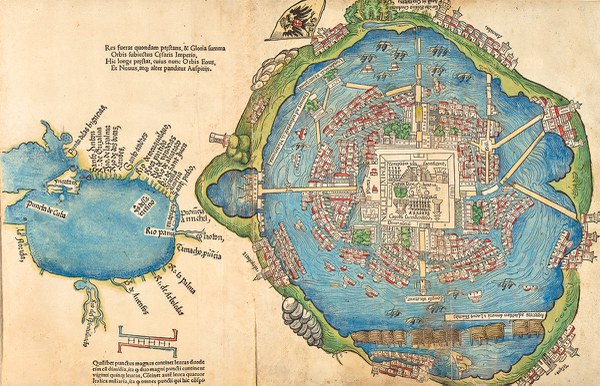

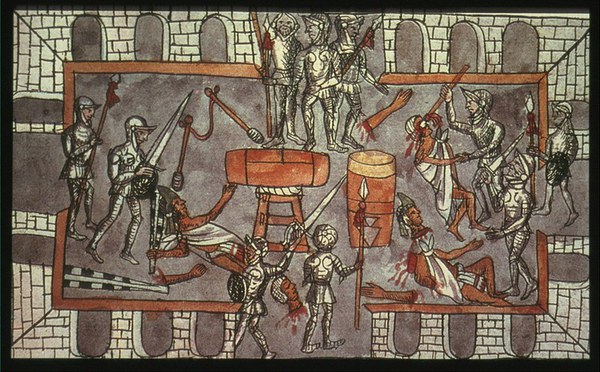

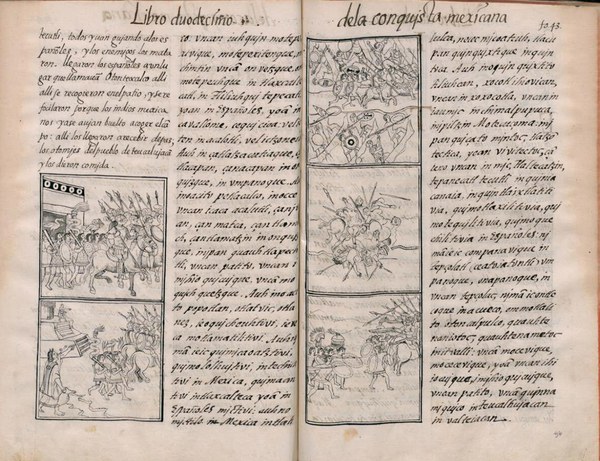

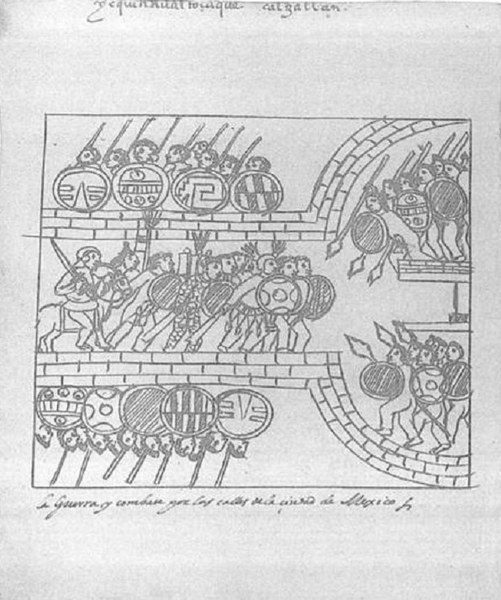

The history of the “conquest of Mexico” has long been obscured by prevailing fictions and fanciful mythmaking, framed as a feat of Spanish military boldness, a triumph of Hernán Cortés over the backward and superstitious Aztec Empire. But this is history written by the victors—an imagined tale, a piece of propaganda repeated in documentaries, textbooks, literature, and operas for centuries. For the people of Mesoamerica, this was no tale of Spanish military prowess. Spanish armies were in fact initially decimated and repelled by the Aztec military. But the European intruders left behind contagious diseases that collapsed Aztec society in a matter of months, making it vulnerable to Mesoamerican rivals and the surviving Spanish forces. This section examines the fall of the Aztec Empire through sources produced by Nahua artists that foreground the role that germs played in the Spanish invasion, focusing on the devastating epidemic outbreak of 1520 and the fall of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, in 1521.

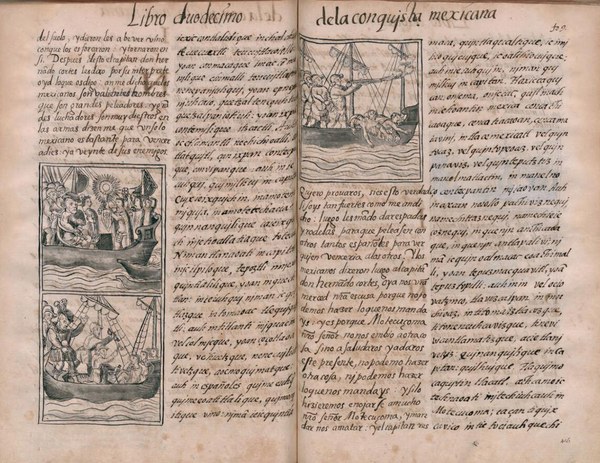

This image is a print re-creating the encounter between Montezuma and Cortés in November 1519. Spanish sources have claimed that Montezuma was a meek leader who surrendered to Cortés shortly after the meeting. It is more likely that Montezuma received Cortés in a gesture of good diplomacy, and that hostilities did not begin until months later.

Image Source

- Portraits and Historical Scenes from the Conquest of Mexico and Central America. Brussels, ca. 1675–1700. P. 36, plate 2. Courtesy Dumbarton Oaks, © Rare Book Collection, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University.

Further Reading

- Cook, Noble David. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. New Approaches to the Americas. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Restall, Matthew. When Montezuma Met Cortés: The True Story of the Meeting That Changed History. New York: Ecco, 2018.