Although I grew up in the southern Indian metropolis of Bangalore, nature played a big role in my childhood. Geographically, we are close to a region known as the Western Ghats—a mountain range that snakes up the west coast of India, much of it cloaked in tropical rainforest. The Western Ghats are also dotted with plantations growing all manner of tropical exports: tea, coffee, vanilla. Being only a few hours’ drive from Bangalore, the Ghats were where my family and I would escape the first chance we could, and so they have always held special significance. My maternal uncle was so in love with the area that he spent his scientific career documenting its flora for the Smithsonian Foundation. And so ever since I was a child, I have associated botany with adventure, discovery, and excitement.

Later on, as I embarked upon a career in the arts, I knew that botanical illustration was what intrigued me the most. My knowledge of the genre was limited to examples from the days of the British East India Company, which laid the foundations for the British Empire in India. Those botanical paintings belonged to the Company School of art, a title derived from the fact that they were usually commissioned by Company officials and executed by local artists. The main purpose of these works was to document and record scientifically the subcontinent’s natural history. What relevance could this old-fashioned, colonial art form have to twenty-first century India, where a single camera can seemingly do the work of a hundred artists?

My first big project taught me a lot about the power of illustration. I worked in collaboration with two conservationists, Divya Mudappa and T. R. Shankar Raman, who run a rainforest restoration program in the Western Ghats. Their aim is to encourage and assist plantation owners in growing native trees on their spare land, or as a canopy for shade-grown coffee—an ecologically sustainable alternative to fast-growing exotic tree species. This is crucial to reduce fragmentation of the jungle, creating passages of native forests between plantations that provide crucial corridors for animals. Without such wildlife corridors, animals may become isolated in small pockets, leading to a number of problems including forced inter-breeding and limited genetic differentiation. Plant-animal relationships can be highly specialized, even exclusive. Animals, insects, amphibians and birds depend on specific native plants for their nutrition and habitat, and may be threatened with extinction in their absence.

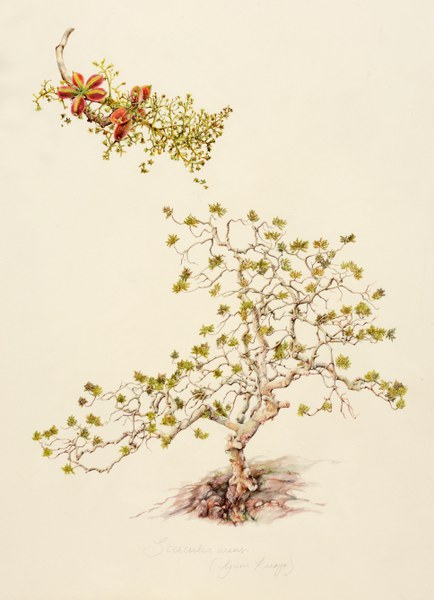

Fig. 21. Nirupa Rao, Strangler Fig (2017).

Members of the Ficus or “fig” genus, for instance, are often called “keystone species” for the important role they play in forest ecosystems. Many species of wild fig trees produce fruit at any time of year, sustaining birds, bats and mammals when other food is scarce. Such keystone species help hold a system together, and their absence could have a dramatic effect on the structure of an ecological community, even threatening its continued existence.

Besides their ecological significance, fig species are truly fascinating in their own right. They often exhibit an adaptation to overcome the difficulties of growing in dense, dark rainforests, where competition for sunlight, water and nutrients is stiff. They begin their lives as epiphytes, germinating on the branches or crooks of existing trees; as they grown, they attract a plethora of seed-dispersing animals, serving as hubs around which biodiversity blooms (fig. 21).

Divya and Shankar were keen to document visually these magnificent trees but photography posed many problems. The trees were too tall to capture in one camera frame, and the surrounding foliage was often too dense to permit the isolation of a single specimen in the tangled forest vegetation. Even while standing right in front of some of these 140 feet tall species, I could not see the entire tree. However, with my botanical illustration in mind, I could study the buttress up close, and then climb further up the hill to see its crown rising above the canopy. In my drawing, I could stitch these pieces of the puzzle together, filling in with Divya and Shankar’s botanical expertise what I could not see with my own eyes.

For some species we were unable to find a fully-grown specimen that was clearly visible. So I studied a sapling instead, and proportionately scaled it up to a fully grown tree. One of the hallmarks of botanical illustration is that it allows you to create an idealized version of a species drawn from careful study of several specimens. That is one of the qualities that make botanical illustration such a crucial tool for identifying plant species.

In addition to these scientific aims, we had another urgent goal: to help people notice and fall in love with these local, everyday trees that may lack the showy flowers or fruit of exotics brought from across the world. I have found that the act of drawing—the long “encounter,” the observation, the collaboration with scientists, the re-creation—not only affords me a personal communion with the individual plant; it also allows the viewer to see these plants afresh through my eyes, providing a welcome defamiliarization and renewed perception of organisms that may seem inert and uncharismatic.

It is with these motivations that I approach projects like my second book on ‘fantastical’ plants of the Western Ghats. With my illustrations, I aim to open young (and adult!) minds to the wonders of the plant world. Through carnivores and parasites and flowers that stink of rotting flesh, I hope to influence peoples’ perception of plants, showing their complexity, agency and resilience. At home in India, my scientific collaborators and I have turned my illustrations into board games that teach school children who live in areas abutting national parks about the plenitude of the natural environment that surrounds them and the urgent need to recognize and protect its significance. No longer confined to the Company School genre, botanical illustration can serve the urgent twenty-first-century purpose of conservation.

The medium of watercolor is slow, painstaking, and does not allow for many mistakes. For instance, watercolorists often avoid white paint, relying instead on the natural hue of the paper to avoid inconsistencies in texture that arise from thick white paint. This proved especially difficult in my painting of Sundews, in which a number of dewy white droplets had to be carefully achieved (fig. 22). Despite its difficulties, to me the unhurried pace of watercolor painting has an affinity with the protracted time scale of the plant kingdom. It captures the wonderful lightness of plants—their springy adaptability, their ephemerality, their quiet tenacity—one brush stroke at a time.

Fig. 22. Nirupa Rao, Sundews (2018). From bottom to top: Drosera burmannii (Tropical Sundew), Drosera indica (Flycatcher), and Drosera peltata [new name Drosera lunata] (Shield sundew).

Nirupa Rao is a botanical illustrator based in Bangalore, India. Her work is inspired by regular field visits into the wild and informed by close collaboration with natural scientists to achieve accuracy. A National Geographic Young Explorer, Rao received a grant to create her book Hidden Kingdom: Fantastical Plants of the Western Ghats (2019). She has also published Pillars of Life: Magnificent Trees of the Western Ghats (2018), a debut project in collaboration with naturalists Divya Mudappa and T. R. Shankar Raman of the Nature Conservation Foundation. She illustrated the cover of Amitav Ghosh’s latest novel, Gun Island, and rejacketed four of his older novels for Penguin Random House. In collaboration with conservationist Krithi Karanth, Rao also created illustrations for educational games that are used in wildlife conflict–prone schools in rural India. This year, the initiative will reach 400 schools, helping children live in harmony with the natural world. In 2019, she participated in a Plant Humanities summer program at Dumbarton Oaks. She has also been named an INK Fellow, one to “watch out for” in Forbes India’s annual 30 Under 30 issue, and one of Harper’s Bazaar India’s ‘“Indian Women to be Proud Of.”

Nirupa Rao is a botanical illustrator based in Bangalore, India. Her work is inspired by regular field visits into the wild and informed by close collaboration with natural scientists to achieve accuracy. A National Geographic Young Explorer, Rao received a grant to create her book Hidden Kingdom: Fantastical Plants of the Western Ghats (2019). She has also published Pillars of Life: Magnificent Trees of the Western Ghats (2018), a debut project in collaboration with naturalists Divya Mudappa and T. R. Shankar Raman of the Nature Conservation Foundation. She illustrated the cover of Amitav Ghosh’s latest novel, Gun Island, and rejacketed four of his older novels for Penguin Random House. In collaboration with conservationist Krithi Karanth, Rao also created illustrations for educational games that are used in wildlife conflict–prone schools in rural India. This year, the initiative will reach 400 schools, helping children live in harmony with the natural world. In 2019, she participated in a Plant Humanities summer program at Dumbarton Oaks. She has also been named an INK Fellow, one to “watch out for” in Forbes India’s annual 30 Under 30 issue, and one of Harper’s Bazaar India’s ‘“Indian Women to be Proud Of.”