Hanging with Hestia Polyolbus

| Accession number | BZ.1929.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

ca. 6th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (weft) 114.5 cm × W. (warp) 138.0 cm (45 1/16 × 54 5/16 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool |

| Acquisition history |

Dikran G. Kelekian (1868–1951), New York and Paris; Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, Dumbarton Oaks, purchase, 1929; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940.

|

Detailed dimensions

Height (weft direction): 114.5 cm

Width (warp direction): 138.0 cm

Hestia from top of halo to tip of proper right shoe: 101.8 cm

Head of Hestia, from top of halo to top edge of jeweled collar: 29.1 cm

Height of right figure, from top of halo to edge of fabric: 76.6 cm

Head of right figure, from top of halo to top edge of jeweled collar: 24.0 cm

Height of left figure, from top of halo to tip of big toe: 78.5 cm

Head of left figure, from top of halo to top edge of jeweled collar: 23.4 cm

Height of central right genius, from top of head to tip of toes of proper left foot: 34.0 cm

Maximum height of bottom yellow band: 3.8 cm

Materials

Warp: Wool, single spun S-direction (S), 9–12/cm; pinkish orange

Weft: Wool, single spun S-direction (S), 16–64/cm; red, orange, pink, yellow, green, blue, purple, brown, beige

Supplementary weft: Wool, single spun S-direction (S); beige

Technique

Tapestry weave

Discussion

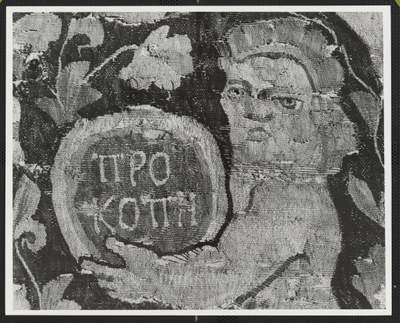

This fragment of a hanging was woven in tapestry weave with colored wool weft on a pinkish-orange wool warp. The partially exposed warp adds to the overall coloring of the textile by giving it a reddish appearance. This hanging was woven with the image perpendicular to the warp, or sideways to the weaver. Once removed from the loom, the weaving was turned 90 degrees clockwise to show the composition in the intended direction. This practice allowed the weaver to facilitate certain technical features within tapestry weave, especially the use of hatching. Hatching indicates shading and is most notably observed in the folds of the figures’ garments and the pink cushion on the throne. Color junctures are achieved with short slits and dovetailing; non-horizontal wefts emphasize contours. Supplementary wefts in beige wool were used sparingly in the lettering of the Πs of ΠΡΟΚΟΠΗ. To enrich the color palette, differently colored fibers were spun together: The warp is spun of various shades of pinkish-orange fibers; the grayish pink of the shading below the figures’ eyes is a blend of medium blue, light blue, and pink fibers; the purple-colored hairline of the figure on the right is composed of dark blue, light blue, and pink fibers. The unevenly spun wool weft in the dark background is composed of fibers of various blue and green hues, giving it an irregular appearance.

Along the bottom edge, fragments of a yellow and red border are preserved. The fragment at the outermost left is not continuous to the remainder of the border, suggesting that it could belong to a different part of the weaving that is now missing. The section below the lower left genius is continuous to the remainder of the textile. Here, along the bottom edge of the yellow band, stitch holes and remnants of what appears to be blue sewing thread in wool can be observed. A small remnant of plied red wool thread is noticeable in the detached border fragment below the left edge of Hestia’s throne.

The weaving has a distinctive arched shape. Close examination revealed that it was not woven to shape. Instead, the textile was cut to create the present shape. While the current right and left edges are fragmented, starting at the approximate height of the upper left and upper right genii, a cut was carefully made along the color edges of slits. Most importantly, along the top edge, above the inscription, the blue wefts turn around the same warp. Some of these wefts stand out as their turn has created small loops, evidence of dovetailing. Both of these technical details confirm that the weaving must have once continued to an adjacent field that is now missing (see further discussion in art historical section).

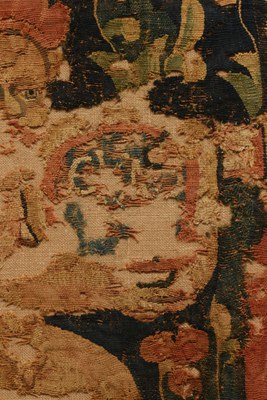

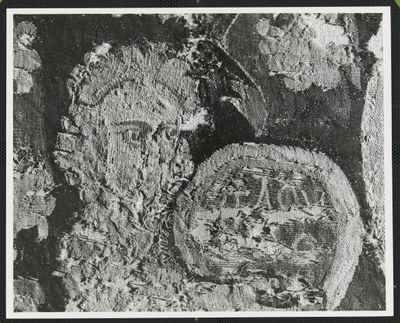

Upon close examination, it is noticeable that the warps in the faces of the upper left and lower left genii are running vertically to the composition, while in the remainder of the weaving the warps run horizontally. The faces might be from a different part of the hanging, now missing, and have been placed here at a more recent date. Details of the heads that were originally in these locations, such as the hair curls, are still visible.

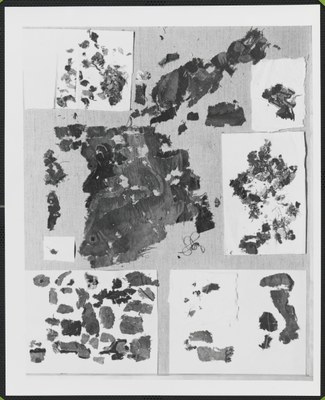

Condition

This is a fragment of a larger textile. It is composed of many pieces. Some of the smaller pieces are not continuous to the weaving and their current placement cannot be confirmed. There are holes and warp and weft loss throughout. Large areas are missing, such as the majority of the left figure and parts of Hestia. The edges are fragile. There is soiling throughout and the color preservation is compromised. Residue of an adhesive from a previous conservation treatment can be observed.

Conservation history

Reconstruction of the composition and mounting (1937); repair and replacement of backing (1963); replacement of backing panel (1989); examination, surface cleaning, and replacement of backing materials (2002)

—Kathrin Colburn, July 2019

| Accession number | BZ.1929.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

ca. 6th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (weft) 114.5 cm × W. (warp) 138.0 cm (45 1/16 × 54 5/16 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool |

| Acquisition history |

Dikran G. Kelekian (1868–1951), New York and Paris; Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, Dumbarton Oaks, purchase, 1929; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940.

|

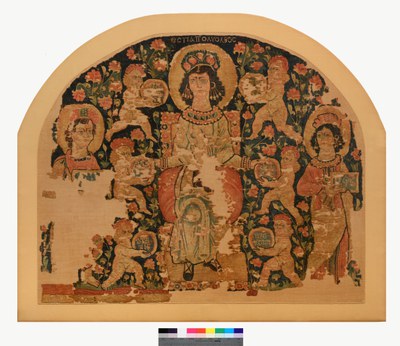

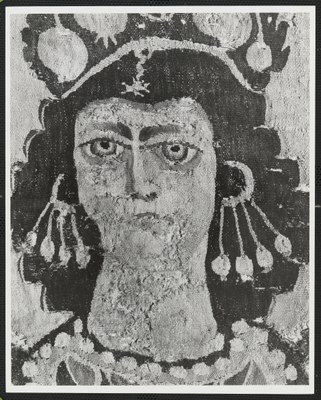

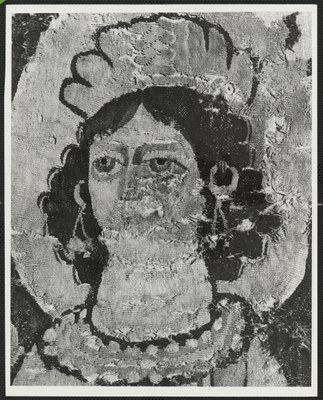

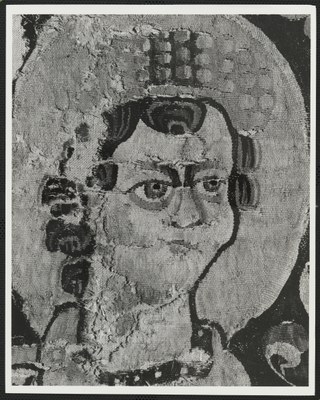

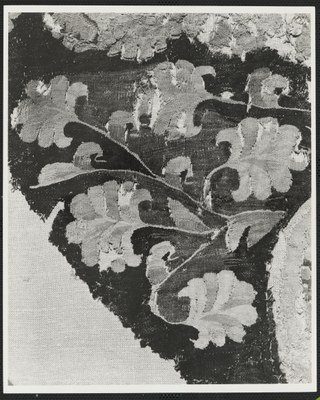

The irregularly shaped fragment depicts a central, haloed female figure, who sits on a gem-encrusted throne upon a plush pink cushion. A wreath with fruits resembling pomegranates is perched above her dark hair. The figure wears a richly draped but unadorned tunic in pale blue, which is accessorized with extensive jewelry, including pearl earrings, a pearl- and gemstone-studded collar, and pairs of gold bracelets over her pearl-covered cuffs. A dark purple-colored area at the center of her lap is difficult to read due to the deterioration of the fabric. Above her head, woven into the blue background color in white, is an inscription identifying her as Εστια ΠολΥολβος (Hestia, Full of Blessings). The ground around Hestia, woven in a dark blue, is filled with pink flowers on vine-like green stems.

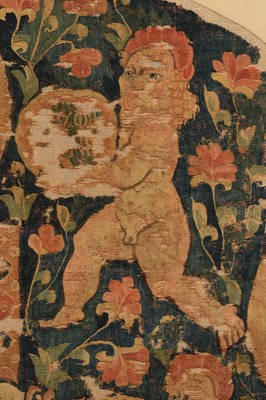

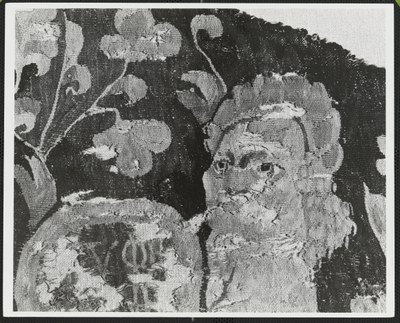

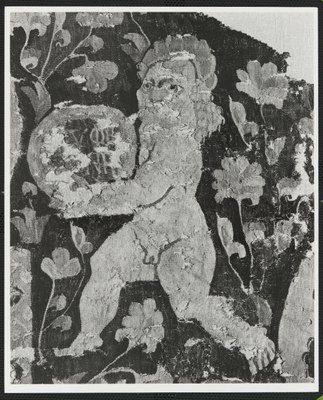

Hestia is symmetrically flanked by a total of six small nude boys—resembling putti or genii— who seem to walk briskly toward her. The boys are nearly identical to one another, with curly blonde hair and pink floral wreaths crowning their heads. Each holds a disk resembling a round platter or tray in their outstretched hands. Though the Greek letters on their disks have partially degraded, it is possible to discern and reconstruct inscriptions that name specific gifts or attributes. Starting at top left, going down, the inscriptions read: Πλουτος (wealth, riches), [Ε]υφρο[συν]η (mirth, cheerfulness), Ευλο[για] (praise, fair, fame, good report), Ευωχ[ι]α (festivity, entertainment, abundance), Αρετη (excellence, virtue, merit), and Προκοπη (progress, improvement).The terms are listed and translated in P. Friedländer, Documents of Dying Paganism: Textiles of Late Antiquity in Washington, New York, and Leningrad (Berkeley, 1945), 7. These attributes make it possible to identify the small boys as genii, or allegorical figures associated with the attributes they offer. Hestia, while facing the viewer frontally, reaches both her arms outward and grasps the two middle disks.

Flanking this central depiction and immediately adjacent to the rigidly stacked genii, two full-length haloed figures, one male and one female, turn toward Hestia. At left, a male figure with short brown hair and an elaborate headdress resembling a wreath with red fruits is only partially preserved. The top of his mantle and tunic are visible, as is his left foot. At right, a female figure stands similarly facing toward the center, though her body’s position is turned more frontally. Her hair style is similar to Hestia’s rich and wavy dark hair, though her pink headdress is different and her jewelry is less lavish, with pendant earrings that feature not four but only two strands or chains. Both these framing figures hold unidentifiable rectangular objects—we may identify them as gray boxes or trays—inscribed with Greek letters, though only the right one preserves enough detail to identify the word Φως (light).

This textile counts as one of the Dumbarton Oaks collection’s most iconic works. It was acquired in June 1929 from the dealer Dikran Kelekian, who claimed that it had been found in Sohag, Egypt. Correspondence between Royall Tyler and Mildred Bliss suggests that the textile hanging was in high demand at the time of its purchase,“I saw Kelekian again before leaving Paris. I had already told him that no name must be mentioned in connexion with the Copt. tapestry. The last time I saw him, last Friday, he told me that Mrs. Arthur Sachs had been to see him to enquire about the tapestry, and had said that her husband, who had just arrived in Paris, was very much interested. K. told her that the tapestry was sold (mentioning no name), whereupon, according to K., Mrs. Sachs said, with some warmth, that it served her husband right.” Royall Tyler to Mildred Bliss, June, 17, 1929. https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/1928-1933/17jun1929. probably thanks to the publicity drummed up a few years prior in an Art News article penned by the well-known Persian art historian and textile specialist Phyllis Ackerman.P. Ackerman, “An Unique VIth or VIIth Century Coptic Tapestry,” The Art News, November 13, 1926. In this earliest publication, Ackerman situated the fabric with Hestia in the art historical discussions of the time, which were broadly concerned with the distinctions between Eastern and Western styles of art.The discussion is rooted in art historical debates about the “Oriental” or “Western” origins and stylistic features of art produced in the late antique and early medieval period, which can be traced to Josef Strzygowski’s Orient oder Rom (Leipzig, 1901). For a historiographical discussion, see J. Elsner, “The Birth of Late Antiquity: Riegl and Strzygowski in 1901,” Art History 25, no. 3 (2005): 358–79. Ackerman posited that the tapestry was a representative of a “lost” style of Hellenistic art believed current in late antique Alexandria. She also presented the textile as a precursor to the great tapestries of Gothic Europe.“This piece is of great interest as an historical document, not only because it is a significant social record of the period and a striking example of the East Mediterranean art that derived directly from the late Hellenistic tradition, but also because it is this style of tapestry that was the direct forerunner of the Gothic tapestry of Europe and this piece fills in an essential link in the chain of its derivation, the next link consisting of the head of St. Theodore from the collection of Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., now on exhibition in the Fine Arts Building of the Sesquicentennial Exposition.” Ackerman, “Coptic Tapestry.”. The Theodore piece is now held in the Harvard Art Museums, 1939.112.1, https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/art/213118.

Hestia traveled from the United States to Paris only two years later for the first blockbuster exhibition on Byzantine art, the Exposition internationale d’art byzantin, held in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in May 1931.Exposition internationale d’art byzantin, 28 mai–9 juillet 1931 (Paris, 1931), no. 190 bis, p. 92, plate VII. Because the Hestia was shipped independently from the United States to Paris, it was the single most expensive loan in the show, a point which set off a flurry of correspondence among the French organizers. Documentation related to the loan of Hestia to the Exposition internationale d’art byzantin are housed in the archives of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. Élise Barzun was instrumental in facilitating research visits by Elizabeth Dospěl Williams. This exhibition proved formative for the field of Byzantine art history as it came to be defined in both Europe and the United States; many of the works featured in the show appeared in Hayford Peirce and Royall Tyler’s encyclopedic book L’Art Byzantin, including Hestia.H. Peirce and R. Tyler, L’Art Byzantin (Paris, 1932), 2:83–84, plates 153–54. In these early publications, Hestia is seen as representing the summit of early Byzantine textile arts, as well as a testimony to the long life of the classical past preserved in the arts of Constantinople.

Scholarly attention has equally focused on the textile’s peculiar iconography and inscriptions. Hestia, the goddess of the hearth, is not frequently depicted in late antique art, or even in ancient art more generally. The composition on the Dumbarton Oaks hanging is unique.Important is the fragment of a tapestry-woven roundel in the Brooklyn Museum (49.19, ca. 20 × 20 cm) that bears striking compositional similarities, though on a much smaller scale; see D. Thompson, Coptic Textiles in the Brooklyn Museum (New York, 1971), 38–40, no. 14. Thompson’s identification of the centrally enthroned female as a Byzantine empress is not convincing, and the overall deteriorated state of preservation does not allow further conclusions at that point. In an unpublished 1940 catalogue entry, the renowned textile scholar Frances Morris takes pains to outline the Greek and Egyptian sources for the textile’s technique and iconography, paying special attention to parallels with painting and mosaics.F. Morris, “Catalogue of Textile Fabrics, The Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1940), 203. Morris draws parallels with imperial and religious art, from wall paintings in Bawit to the mosaics of Ravenna, all in an effort to situate Hestia in both time and place.

While the art historians Ackerman, Tyler, Peirce, and Morris focused on iconographic and stylistic parallels, the classical philologist Paul Friedländer took a more literary approach to the textile in his 1945 book Documents of Dying Paganism.Friedländer, Documents of Dying Paganism, 1–26. Friedländer turned his attention to the inscriptions, noting that Hestia’s unusual epithet “Full of Blessings” has a long life in ancient Greek literature, particularly in the Orphic hymns. He also considered the “blessings” inscribed on the disks in the putti’s hands, as well as the representation of the two adult flanking figures, and linked them to Neoplatonic and other philosophical ideals. All in all, Friedländer saw the Hestia textile as representing a pivotal cultural moment when the ancient world transitioned to the medieval one.

In her essay on this work, Sabine Schrenk revisits the question of the textile’s iconography, and argues against previous interpretations of the two standing figures as donors. She reads the depiction as a visualization of the majestic and varied powers of the goddess Hestia, and interprets those surrounding her as followers of equal stature to her. Schrenk seeks the iconographic roots of the Hestia hanging in late antique imperial art on the one hand, and religious depictions on the other.Cleveland Museum of Art, 1967.144, http://www.clevelandart.org/art/1967.144.

Another complicating aspect of the textile hanging concerns the fragment’s arched shape, which is evident even in the earliest surviving archival photographs of the piece. This peculiar feature led Frances Morris in her unpublished catalogue of 1940 to suggest that the piece was created in this shape in order to hang in a niche.Morris, “Catalogue,” 203. In his 1945 publication, Paul Friedländer, unaware of Morris’s work, similarly concluded that “it was designed to fit into an architectural frame, the whole being in the shape of a horizontal rectangle with an arched upper edge.”Friedländer, Documents of Dying Paganism, 1–2. Deborah Thompson, in an unpublished 1976 catalogue, came to a similar conclusion, which she bases on her interpretation of the technical structure of the curved area of the piece. According to her, “the wefts of the rounded sides give every sign of having been cut in antiquity . . . the hanging was designed to fit into a curved architectural space such as a lunette or niche.”D. Thompson, “Catalogue of the Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection,” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1976), 345, no. 47. As Kathrin Colburn’s technical analysis elaborates, there are both continuous weft threads along the upper edge, immediately above the Hestia inscription, and cut weft threads along the two curved sides. This technical evidence demonstrates that the textile in its current state does not represent the selvage of the hanging, but rather was more likely a border between color fields, which was later partially cut to its current shape. These observations make clear without doubt that we can firmly put to rest the idea that this hanging was a customized architectural furnishing made to fit the outline of a lunette. Instead, the hanging’s original shape was very likely rectangular and thus not different from most hangings known and preserved in late antique and early Byzantine Egypt.

—Gudrun Bühl and Elizabeth Dospěl Williams, May 2019

Notes

| Accession number | BZ.1929.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

ca. 6th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (weft) 114.5 cm × W. (warp) 138.0 cm (45 1/16 × 54 5/16 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool |

| Acquisition history |

Dikran G. Kelekian (1868–1951), New York and Paris; Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, Dumbarton Oaks, purchase, 1929; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940.

|

Paris, Musée des arts décoratifs, Exposition internationale d’art byzantin, May 28–July 9, 1931.

Worcester, MA, Worcester Art Museum, Art of the Dark Ages, February 20–March 21, 1937.

Washington, DC, The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Woven Interiors: Furnishing Early Medieval Egypt, August 31, 2019—January 5, 2020.

| Accession number | BZ.1929.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

ca. 6th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (weft) 114.5 cm × W. (warp) 138.0 cm (45 1/16 × 54 5/16 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool |

| Acquisition history |

Dikran G. Kelekian (1868–1951), New York and Paris; Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, Dumbarton Oaks, purchase, 1929; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940.

|

P. Ackerman, “An Unique VIth or VIIth Century Coptic Tapestry,” The Art News (November 13, 1926).

Exposition internationale d’art byzantin, 28 mai–9 juillet, 1931; Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Palais du Louvre, Pavillon de Marsan (Paris, 1931), no. 190, p. 92, plate VII.

W. F. Volbach, “Die byzantinische Ausstellung in Paris,” Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst 65 (1931–32): 102–113, illustration p. 109.

G. Hanotaux, ed., Histoire de la nation égyptienne (Paris, 1931–40), 3:481.

H. Peirce and R. Tyler, L’art byzantin (Paris, 1932–34), 2:91–92, figs. 153–54.

P. Ackerman, Tapestry, the Mirror of Civilization (New York, 1933), 20–21, plate 3.

W. F. Volbach, G. Duthuit, and G. Salles, Art byzantin (Paris, 1933), 73, fig. 84.

D. Talbot Rice, Byzantine Art (Oxford, 1935), 178.

L. Bréhier, La sculpture et les arts mineurs byzantins (Paris, 1936), 96–97, fig. 79.

S. Cheney, A World History of Art (New York, 1937), 331.

The Dark Ages: Loan Exhibition of Pagan and Christian Art in the Latin West and Byzantine East (Worcester, MA, 1937), 46, no. 140, plate 140.

C. R. Morey, “Art of the Dark Ages: A Unique Show. The First American Early Christian-Byzantine Exhibition at Worcester.” Art News 35, no. 21 (1937): 9–16, 24, esp. 16.

R. Tyler, “Fragments of an Early Christian Tapestry,” Bulletin of the Fogg Art Museum 9, no. 1 (1939): 2–13, esp. 8–9, plates 6–7.

F. Morris, “Catalogue of Textile Fabrics, The Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1940), 199–205.

G. Downey, “The Pagan Virtue of Megalopsychia in Byzantine Syria,” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 76 (1945): 283.

P. Friedländer, Documents of Dying Paganism: Textiles of Late Antiquity in Washington, New York, and Leningrad (Berkeley, 1945), color frontispiece and pp. 1–26.

Dumbarton Oaks, Handbook of the Collection (Washington, DC, 1946), 126–27, no. 248, fig. on p. 135.

“Reawakening at Dumbarton Oaks: The Golden Glories of the Byzantine and Early Christian Worlds,” Art News 45, no. 10.1 (1946): 15–19; 57–-59, esp. 19, plate III, color plate front cover.

R. Bianchi Bandinelli, Hellenistic-Byzantine Miniatures of the Iliad (Ilias Ambrosiana) (Olten, 1955),155, plate 231.

Dumbarton Oaks, The Dumbarton Oaks Collection, Harvard University: Handbook (Washington, DC, 1955), 155, no. 301, fig. on p. 160.

G. Manganaro, “La dea della casa e la Euphrosyne nel Basso Impero,” Archeologia Classica: Rivista dell'Istituto di archeologia della Università di Roma 12, no. 2 (1960): 189–207; plate LXI, 1.

K. Wessel, Koptische Kunst: Die Spätantike in Ägypten (Recklinghausen, 1963), 214–15, plate 132.

W. F. Volbach, Il tessuto nell'arte antica (Milan, 1966), plate 32.

Dumbarton Oaks, Handbook of the Byzantine Collection (Washington, DC, 1967), 108, no. 364.

W. F. Volbach, Early Decorative Textiles (London, 1969), plate 32.

E. Simon, Meleager und Atalante: Ein spätantiker Wandbehang Monographien der Abegg-Stiftung (Bern, 1970), 41–44, plate 17.

D. Thompson, “Catalogue of the Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1976), no. 47.

H.-D. Saffrey, “Néo-Platoniciens (les) et les mythes Grecs,” in Dictionnaire des mythologies et des religions des sociétés traditionnelles et du monde antique, ed. Y. Bonnefoy (Paris, 1981), 2:159–60.

F. Muthmann, Der Granatapfel: Symbol des Lebens in der alten Welt (Fribourg, 1982), 130–34, plates 110–11.

M.-H. Rutschowscaya, Coptic Fabrics (Paris, 1990), 118.

L. von Wilckens, Die textilen Künste von der Spätantike bis um 1500 (Munich, 1991), 32, plate 29.

I. Kalavrezou, Byzantine Women and Their World (Cambridge, MA, 2003), 163, 177, plate 15.

A. Kirin, J. N. Carder, and R. S. Nelson, Sacred Art, Secular Context: Objects of Art from the Byzantine Collection of Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C., Accompanied by American Paintings from the Collection of Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss (Athens, GA, 2005), 23, 48.

G. Bühl, ed., Dumbarton Oaks: The Collections (Washington, DC, 2008), 62.

J. Harris, ed., 5000 Years of Textiles (Washington, DC, 2010), 60, plate 57.

G. Bühl and E. Williams, “Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection: Past Studies and Future Directions.” In Textiles, Tools and Techniques: Proceedings of the 8th Conference of the Research Group “Textiles from the Nile Valley,” Antwerp, 4–6 October 2013, ed. A. De Moor, C. Fluck, and P. Linscheid (Tielt, 2015), 68, fig. 6.

T. K. Thomas, ed., Designing Identity: The Power of Textiles in Late Antiquity (Princeton, NJ, 2016), 106–7, figs. 2-3.1, 2-3.2.

J. Ball, “Textiles: The Emergence of a Christian Identity in Cloth,” in The Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art, ed. R. M. Jensen and M. D. Ellison (London, 2018): 232, fig. 14.9.

G. Bühl, S. Krody, E. Dospěl Williams, Woven Interiors: Furnishing Early Medieval Egypt (Washington, DC, 2019), 76-7, no. 29.

| Accession number | BZ.1929.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

ca. 6th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (weft) 114.5 cm × W. (warp) 138.0 cm (45 1/16 × 54 5/16 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool |

| Acquisition history |

Dikran G. Kelekian (1868–1951), New York and Paris; Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, Dumbarton Oaks, purchase, 1929; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940.

|