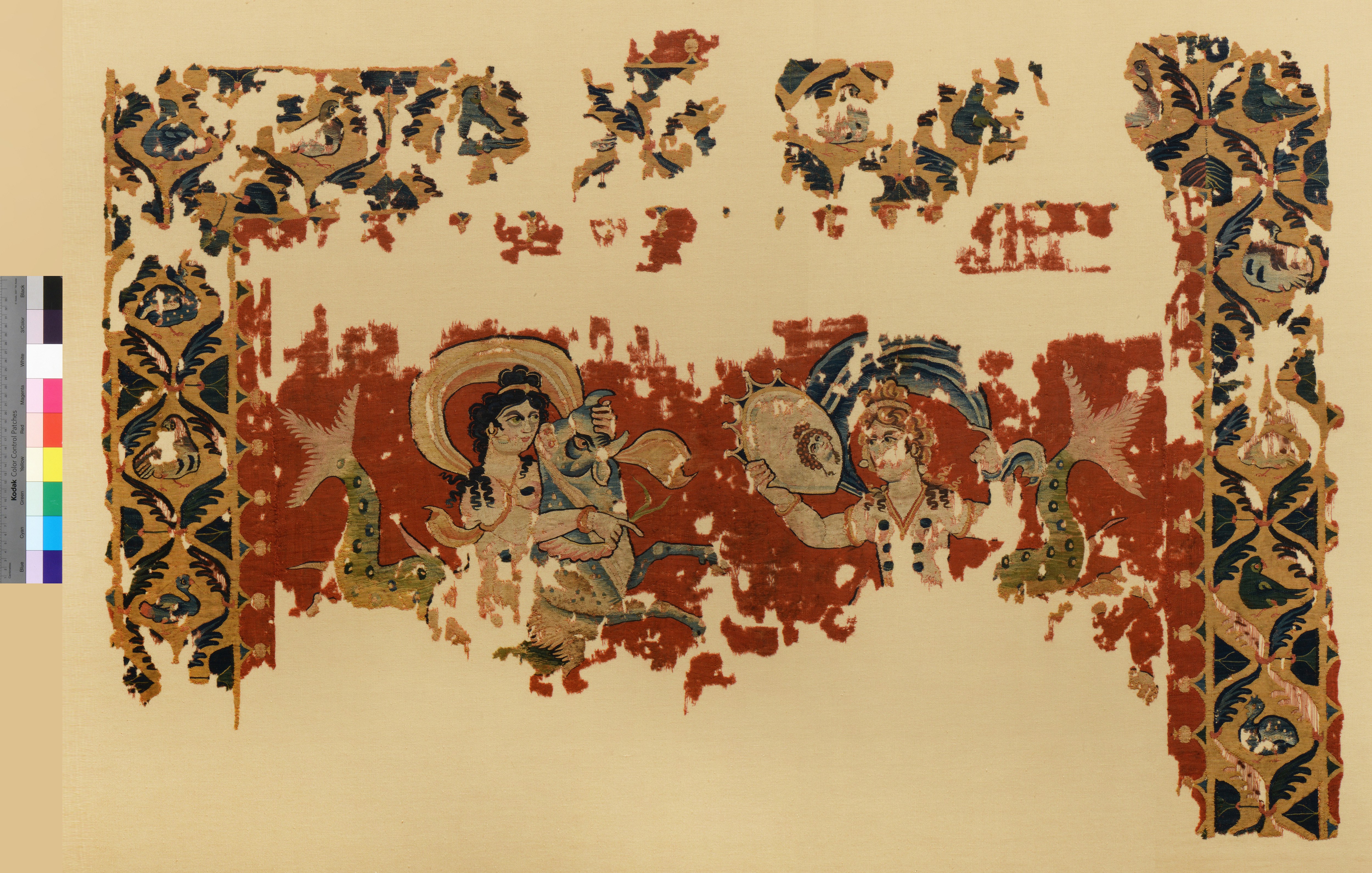

Fragments of a Hanging with Nereids

| Accession number | BZ.1932.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

5th–6th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (warp) 95.0 cm × W. (weft) 143.5 cm (37 3/8 × 56 1/2 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool and undyed linen |

| Acquisition history |

Dikran G. Kelekian (1867–1951), New York and Paris; Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, purchase, 1932; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940.

|

Detailed dimensions

Height: 95.0 cm (warp direction)

Width: 143.5 cm (weft direction)

Height of right Nereid head from chin to hairline: 7.0 cm

Height of left Nereid head from chin to hairline: 6.5 cm

Width of red inner field: 103.0 cm

Width of side borders with birds: 14.0 cm

Width of innermost borders with pomegranates: 4.5 cm

Height of horizontal border with birds: 17.0 cm

Materials

Warp: Wool, single spun S-direction (S), 10–12/cm; pinkish-orange

Weft: Wool, single spun S-direction (S), 32–56/cm; beige, yellow, orange, red, pink, purple, blue, green. Linen, single spun S-direction (S), 32–44/cm; undyed.

Technique

Tapestry weave

Discussion

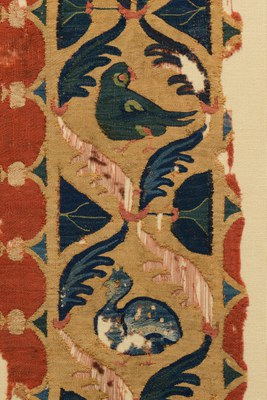

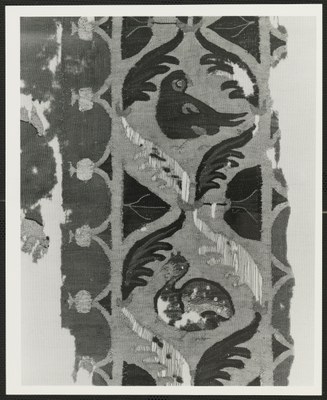

This fragmentary preserved hanging was woven in tapestry weave with colored wool weft on a pinkish-orange wool warp. The warp is partially exposed, giving a reddish appearance to the textile and adding to the subtle, deep red tone of the main field. The width of the red field measures 103 centimeters; due to losses in the lower half, the height of it remains uncertain (see further discussion in art historical section). Color junctures are achieved with short slits and dovetailing; non-horizontal wefts shape contours. In addition, irregular hatching can be observed in areas such as the fish like tails of the sea animals, the billowing mantle cloths of the Nereid’s, and the bodies of the birds in the borders. In some details, such as the face of the bull, colored wool weft and undyed linen weft was placed into the same shed, creating thickness to the weave. To enrich the color palette, different colored fibers were spun together: For example, the medium blue weft consists of light-, medium-, and dark-colored blue fibers; the medium green comprises yellow and fibers of various green hues, and the purplish grey is a combination of blue, pink, and purplish fibers; undyed linen weft was used for small accents, such as the pomegranates in the scalloped borders. In the horizontal border, supplementary weft—in greenish yellow, pink, or different shades of blue—was carried along one continuous warp to create detailing. This technical feature appears most noticeably in the lines that separate the vignettes framed by acanthus leaves. In the vertical borders, similar dividing lines were incorporated into the tapestry weave. Supplementary weft in pink was also used to weave some of the birds’ legs in the borders. Warps were paired to strengthen the edges of the red main field, the outer edges of the innermost scalloped borders, and the yellow right edge of the left vertical border.

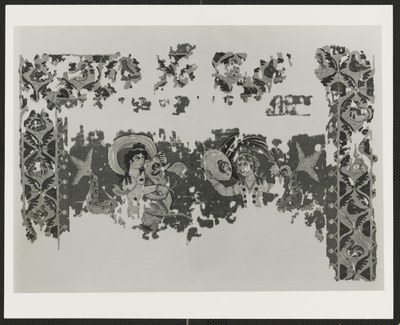

Condition

This is a fragment of a once larger hanging. It is composed of numerous pieces; the placement of the smaller pieces within the composition cannot be confirmed. The lower half of the composition has major losses. There are holes and warp and weft loss throughout. The supplementary weft is abraded and only partially preserved. The edges are fragile. The color preservation is compromised and there is soiling. The purple-brown colored weft in the leaves of the borders has deteriorated more than wefts of other colors. Most likely, the red main field was stitched to the outer borders, but no remnants of the original sewing thread could be observed. No selvages are preserved.

Conservation history

Stitched to a fabric-covered stretcher frame (unknown date); remounted (1974–75); backing replaced (2002)

—Kathrin Colburn, August 2019

| Accession number | BZ.1932.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

5th–6th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (warp) 95.0 cm × W. (weft) 143.5 cm (37 3/8 × 56 1/2 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool and undyed linen |

| Acquisition history |

Dikran G. Kelekian (1867–1951), New York and Paris; Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, purchase, 1932; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940.

|

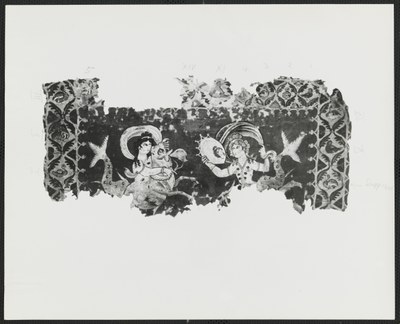

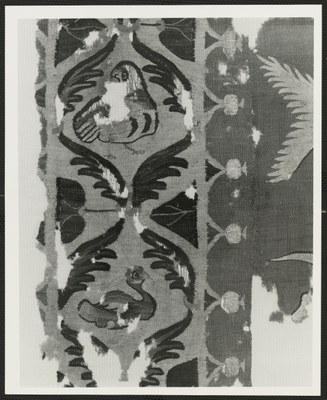

Two confronted female figures, each alongside a sea animal, adorn a large fragment with a red ground. Two tendrils of acanthus leaves fill three surviving borders, consisting of light and dark blue slender leaves on a beige background, interspersed with birds. The birds are carefully differentiated from one another to suggest a variety of species. The border is scalloped along its outer and inner edges; these scalloped features terminate in pomegranates or pearls.

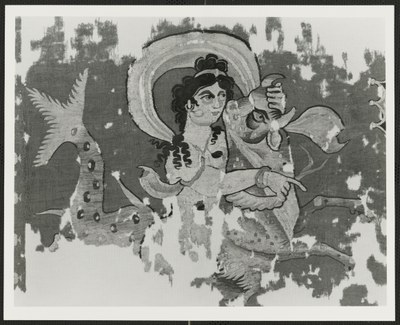

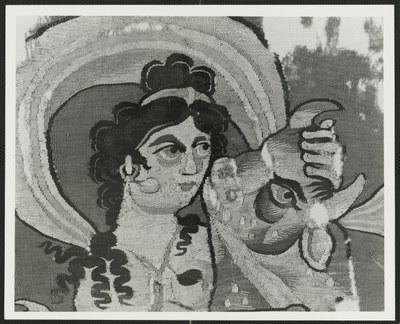

The main field is composed of two female figures riding animals who face each other. Their upper bodies are nearly intact, with losses in the lower halves. The black-haired figure to the left rides a hybrid sea creature with the head of a bull. Although most of her legs have been lost, the sole and heel of one of her feet is visible near the left border, beneath the animal’s fin. She is naked except for the obligatory mantle cloth, fluttering behind her head forming an arch around it. Her black hair falls down to her neck and her shoulders in thick curls; some of the curls are pulled together on top of her head with a yellow-red band, which appears to be decorated with a precious stone. Altogether, hairdo and band resemble a diadem. She gazes and gestures with her right index finger toward the figure on the right and also pulls the end of a ribbon, scarf, or garland forward. The figure wears jewelry, including earrings, two armlets on her right arm and a necklace with a pointed end toward her breasts. Two dark blue spots on her body (one on her left breast and one on her belly) may represent jewelry: one can see the upper black form linked to the V-shaped necklace, probably reaching down to her belly button.

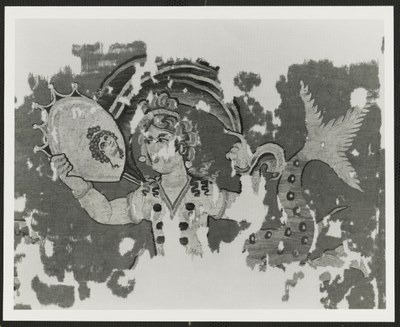

The right female figure also sits atop an animal. Her brown curls fall to her shoulders and are bound with a diadem. Three pairs of black spots or small circles on her upper body appear as part of her jewelry, paralleling the figure at left. Part of her lower leg and foot is visible near the right border, beneath the animal’s fin. She holds a gauzy blue mantle with her left hand, while in her outstretched right hand she holds a richly ornamented mirror, reflecting her own face, her hair rendered in tight circles instead of loose waves.

Both animals have yellow-green fish-like tails speckled with black-and-white circles, terminating in a tripartite beige fin; one or two additional fins rendered as thin beige appendages extend from the tail of each. Only the tail of the animal on the right survives, but the animal on the left retains its upper body in beige and blue, which includes two legs and the head of a bull. This creature turns its head backward to face its rider, appearing to nuzzle her cheek.

This fragment is part of a once larger hanging depicting two Nereids—in Greek mythology the (very numerous) daughters of Nereus and Doris. They are frequently shown accompanied by sea creatures.A number of surviving textiles exhibit similar iconography. A textile in Riggisberg (Abegg-Stiftung, inv. 446) shows a Nereid with similar a hairdo and the style of the face in front of (instead of riding on) a sea animal: S. Schrenk, Textilien des Mittelmeerraumes aus spätantiker bis frühislamischer Zeit (Riggisberg, 2004), 73–74, no. 17; see also a hanging with Nereids at the Textile Museum, 1.48, J. Trilling, The Roman Heritage: Textiles from Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean, 300 to 600 AD (Washington, DC, 1982), 42, no. 20; and a small tabula with Nereid decoration, possibly from a tunic: Washington, DC, Textile Museum, inv. 1960.20.7; Trilling, Roman Heritage, 60, no. 47. For other media, see the examples mentioned in A.-V. Szabados, “Nereides,” LIMC, 6.1:785–824, such as no. 100 (bone relief in Athens, Benaki Museum, inv. 10314, late 3rd to early 4th c.) and a variety of mosaics: no. 110 (in Annaba/Hippo Regius, 2nd half of 3rd c.); no. 241 (upper panel; in Volubilis, House of the Nereids, early 3rd c.); no. 244 (in Algiers, Musée national des antiquités et des arts islamiques, 3rd c.?). The orientation of the Nereids and the birds in the border indicate that the piece had a specific orientation and was meant to be viewed with a specific top and bottom. For the reconstruction of the whole composition, two possibilities are conceivable.

If the hanging was oriented horizontally, then the surviving figures in the central panel very probably were the only ones.Washington, DC, Textile Museum, inv. 71.51 (Trilling, Roman Heritage, no. 19), has two rows. Therefore, probably, the motifs themselves are comparatively small. Alternatively, if the hanging was oriented vertically, we might expect a now-lost scene beneath the Nereids. As a large-scale composition, it is likely the textile was intended as a hanging, rather than lying on the floor or on furniture. Furthermore, given the layout of its design, it was likely not meant to be pushed together or raised like a curtain. Lastly, in comparison with other large wall hangings, it is unusual that the Nereids and their sea-monsters are given such a prominent place in the composition.This arrangement is in contrast to the large Nereid hanging in the Textile Museum (inv. 1.48), but similar to the Dionysus hanging in the Abegg-Stiftung in Riggisberg, inv. 3100a: Schrenk, Textilien des Mittelmeerraumes, no. 1.

Nereids were a fairly popular theme among late antique and Byzantine textiles, so, it is not surprising that they also appear on an wall hanging. As the daughters of Nereus and Doris the Nereids were connected to high-ranking Greek gods. As their home was the sea, they benefited from the enormous popularity of maritime scenes in antiquity and late antiquity, on objects for this life as well as in sepulchral art. Nereids were believed to love music and dance, and conveyed cheer as well as eroticism in both literary sources and works of art.On literary sources, see S. Muth, “Gegenwelt als Glückswelt – Glückswelt als Gegenwelt? Die Welt der Nereiden, Tritonen und Seemonster in der römischen Kunst,” in Gegenwelten: Zu den Kulturen Griechenlands und Roms in der Antike, ed. T. Hölscher (Munich, 2000), 467–98. There are countless examples of Nereids in textiles, mosaic floors, and sarcophagi. On this latter category, see G. Koch and H. Sichtermann, Handbuch der Römischen Sarkophage (Munich, 1982), 195–97; P. Zanker and B. C. Ewald, Mit Mythen leben: Die Bilderwelt der römischen Sarkophage (Munich, 2004), 117–34. Nereids are part of a sea thiasos, that is, a procession, together with other sea gods.Zanker and Ewald, Mit Mythen leben, 129–34; see also J. M. Barringer, Divine Escorts: Nereids in Archaic and Classical Greek Art (Ann Arbor, 1995). But they can also appear isolated on smaller items like mirrors. On many objects, no connection to a precise myth is intended.

The affectionate interaction between the Nereid and creature on the left, and the right Nereid’s demonstration of vanity, a nod to physical beauty, enhance the erotic atmosphere of the scene. These details would likely have appealed to a sophisticated, erudite owner or viewer. The hanging might have been installed in a triclinium (dining room), in a reception hall, or in a more private cubiculum. At any rate, a private villa seems to be its most plausible setting.

—Sabine Schrenk, March 2020

Notes

| Accession number | BZ.1932.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

5th–6th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (warp) 95.0 cm × W. (weft) 143.5 cm (37 3/8 × 56 1/2 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool and undyed linen |

| Acquisition history |

Dikran G. Kelekian (1867–1951), New York and Paris; Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, purchase, 1932; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940.

|

Paris, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Exposition internationale d’art byzantin, May 28–July 9, 1931.

Worcester, MA, Worcester Art Museum, Art of the Dark Ages, February 20–March 21, 1937.

Washington, DC, The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Woven Interiors: Furnishing Early Medieval Egypt, August 31, 2019—January 5, 2020.

| Accession number | BZ.1932.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

5th–6th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (warp) 95.0 cm × W. (weft) 143.5 cm (37 3/8 × 56 1/2 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool and undyed linen |

| Acquisition history |

Dikran G. Kelekian (1867–1951), New York and Paris; Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, purchase, 1932; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940.

|

W. F. Volbach, “Die byzantinische Ausstellung in Paris,” Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst 63 (1930–31): esp. 109.

Exposition internationale d'art byzantin, 28 mai–9 juillet, 1931; Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Palais du Louvre, Pavillon de Marsan (Paris, 1931), 192, no. 734.

G. Hanotaux, ed. Histoire de la nation égyptienne (Paris, 1931–40), 3: plate 11.

H. Peirce and R. Tyler, L’art byzantin (Paris, 1932–34), 1:87–88, plates 141–42.

W. F. Volbach, G. Duthuit, and G. Salles, Art byzantin (Paris, 1933), 72, plate 81.

P. Ackerman, Tapestry, the Mirror of Civilization (New York, 1933), 16, plate 1.

A. J. B. Wace, “The Veil of Despoina,” AJA 38 (1933): 107–11; plate 11.

L. Bréhier, La sculpture et les arts mineurs byzantins (Paris, 1936), 97, plate 80.

S. Cheney, A World History of Art (New York, 1937), 330.

C. R. Morey, “Art of the Dark Ages: A Unique Show. The First American Early Christian-Byzantine Exhibition at Worcester,” Art News 35, no. 21 (1937): 9–16, 24, esp. 16.

The Dark Ages: Loan Exhibition of Pagan and Christian Art in the Latin West and Byzantine East (Worcester, MA, 1937), 46, no. 138, fig. 138.

E. A. Jewel, “Art of the Dark Ages at Worcester,” New York Times, February 21, 1937.

F. Morris, “Catalogue of Textile Fabrics, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1940), 17–25.

Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection of Harvard University, Handbook of the Collection (Washington, DC, 1946), 125, no. 241, plate on p. 133.

A. C. Weibel, Two Thousand Years of Textiles: The Figured Textiles of Europe and the Near East (New York, 1952), no. 3.

Dumbarton Oaks, The Dumbarton Oaks Collection, Harvard University: Handbook (Washington, DC, 1955), 154, no. 298, plate on p. 158.

J. Beckwith, “Coptic Textiles.” Ciba Review 133 (1959): esp. 12, fig. p. 14.

K. Wessel, Koptische Kunst: Die Spätantike in Ägypten (Recklinghausen, 1963), 210, fig. 106.

K. Wessel, Coptic Art, trans. J. Carroll and S. Hatton (New York, 1965), 198, fig. 106.

W. F. Volbach, Il tessuto nell'arte antica (Milan, 1966), plate 4.

A. Grabar, The Golden Age of Justinian, from the Death of Theodosius to the Rise of Islam, trans. S. Gilbert and J. Emmons (New York, 1967), 326, figs. 383–84.

Dumbarton Oaks, Handbook of the Byzantine Collection (Washington, DC, 1967), 107, no. 361, plate 361 (detail).

W. F. Volbach, Early Decorative Textiles (London, 1969), plate 4.

D. Thompson, “Catalogue of the Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1976), no. 49.

D. Thompson, “New Technical and Iconographical Observations about Important Coptic Hangings with Marine and Hunting Themes (1),” BullCIETA 54, no. 2 (1981): 63–81; fig. 2.

F. Muthmann, Der Granatapfel: Symbol des Lebens in der alten Welt (Fribourg, 1982), 139–40, figs. 117–18.

J. Lacarrière, Le livre des genèses (Paris, 1990), 153–54.

M.-H. Rutschowscaya, Coptic Fabrics (Paris, 1990), 120–21.

S. Schrenk, Textilien des Mittelmeerraumes aus spätantike bis frühislamischer Zeit. (Riggisberg, 2004), 73.

G. Bühl, and E. Williams, “Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection: Past Studies and Future Directions,” in Textiles, Tools and Techniques of the 1st Millennium AD from Egypt and Neighbouring Countries: Proceedings of the 8th Conference of the Research Group “Textiles from the Nile Valley,” Antwerp, 4–6 October 2013, ed. A. De Moor, C. Fluck, and P. Linscheid (Tielt, 2015), 66, fig. 5.

B. Verhelst, Direct Speech in Nonnus’ Dionysiaca: Narrative and Rhetorical Functions of the Characters’ “Varied” and “Many-faceted” Words (Leiden, 2017), 240, fig. 6.

G. Bühl, S. Krody, E. Dospěl Williams, Woven Interiors: Furnishing Early Medieval Egypt (Washington, DC, 2019), 45, no. 12.

| Accession number | BZ.1932.1 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

5th–6th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (warp) 95.0 cm × W. (weft) 143.5 cm (37 3/8 × 56 1/2 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool and undyed linen |

| Acquisition history |

Dikran G. Kelekian (1867–1951), New York and Paris; Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, purchase, 1932; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940.

|