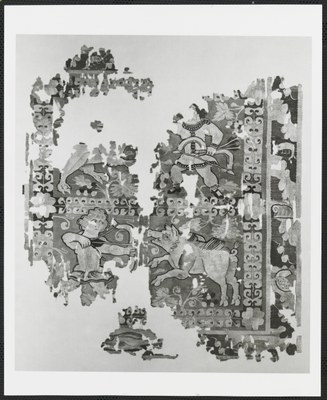

Fragment of a Hanging with Two Hunters

| Accession number | BZ.1937.14 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

7th–9th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (warp) 95 cm × W. (weft) 82.5 cm (37 3/8 × 32 1/2 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool |

| Acquisition history |

Nicholas Tano Collection, Cairo; Paul and Marguerite Mallon Collection, Paris, to 1937 (Marguerite Mallon mentions the tapestry came from “a family in Antioch where it had been for a long time” [letter dated October 25, 1938]); Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, purchase, 1937; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940. |

Detailed dimensions

Height: 95.0 cm (warp direction)

Width: 82.5 cm (weft direction)

Width of red inner field: 56.7 cm

Width of outer right vertical border with sea life: 7.5 cm; including yellow bands: 10.5 cm

Width of inner right vertical border with garland: 6.7 cm

Height of top horizontal border with sea life: 6.0 cm

Height of top horizontal border with sea life: 9.0 cm

Height of top registrar: 30.0 cm

Height of lower registrar: 28.0 cm

Materials

Warp: Wool, single spun S-direction (S), 9–12/cm; various beige tones (undyed?)

Weft: Wool, single spun S-direction (S), 16–54/cm; yellow, red, blue, green, brown

Technique

Tapestry weave

Discussion

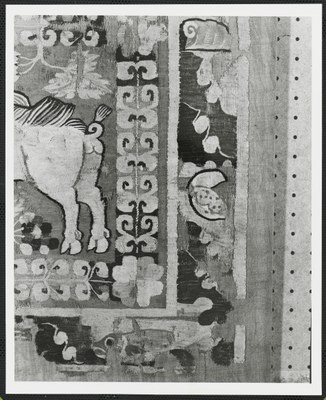

This fragment of a hanging was woven in tapestry weave with colored wool weft on an undyed (?) wool warp. Warps are paired to strengthen the outer edges of the inner and outer vertical yellow borders and both edges of the red inner fields. Color junctures are achieved with short slits and dovetailing; non-horizontal wefts shape contours. In addition, irregular hatching creates volume and form; for example, in the garment of the hunter in the lower left, the boar, and the fish in the center of the bottom border. The seawater in the outer right border was woven by alternating different shades of blue weft. In the inner vertical borders, an almost continuous vertical line of two supplementary wefts in yellow or green wool yarns was carried along one continuous warp to weave the stem that separates the leaves in the foliage. This same design appears in the three horizontal borders, where the stem was incorporated within the tapestry weave. Supplementary weft was also employed for the legs of the pink crustacean in the outer right border. Unevenly spun weft yarns create texture throughout the weaving. The majority of them consist of fibers spun of different colors, with the exception of yellow (as in the bands of the border) and beige (as in the face of the figures).

Condition

This is a fragment of a larger textile. There are holes and warp and weft loss throughout. The edges are fragile. There are discolorations, some staining, and abrasion. The colors have faded, in particular the yellow wool (the most fugitive dye employed) that now appears beige. Hues containing a yellow dye component have faded to a large degree; for example, areas woven with green wool weft now appear bluish green. The paired warp along the right edge of the weaving seems to be a finished edge—the selvage. The placement of the six small fragments in the center of the lower register is questionable.

Conservation history

Mounted on linen (1942); remounted (1984–85); cleaned and remounted (2002)

—Kathrin Colburn, July 2019

| Accession number | BZ.1937.14 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

7th–9th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (warp) 95 cm × W. (weft) 82.5 cm (37 3/8 × 32 1/2 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool |

| Acquisition history |

Nicholas Tano Collection, Cairo; Paul and Marguerite Mallon Collection, Paris, to 1937 (Marguerite Mallon mentions the tapestry came from “a family in Antioch where it had been for a long time” [letter dated October 25, 1938]); Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, purchase, 1937; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940. |

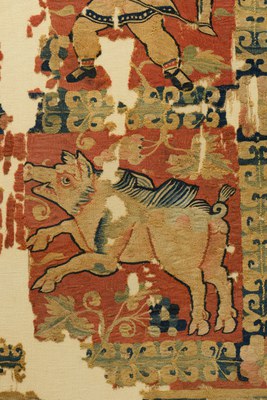

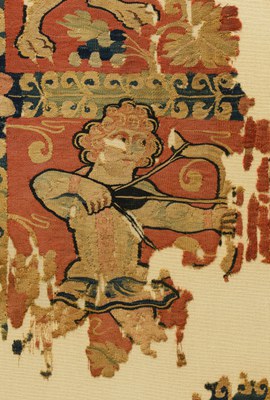

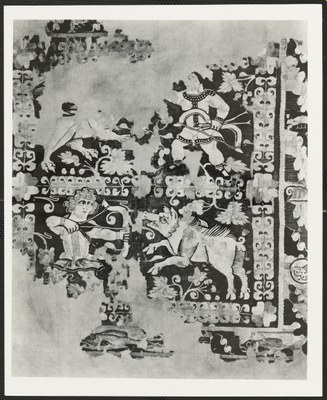

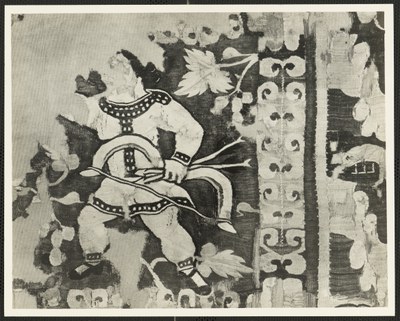

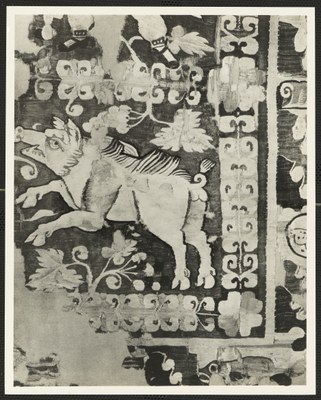

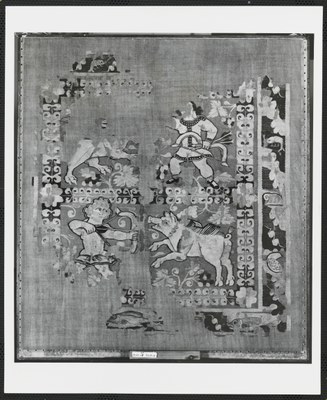

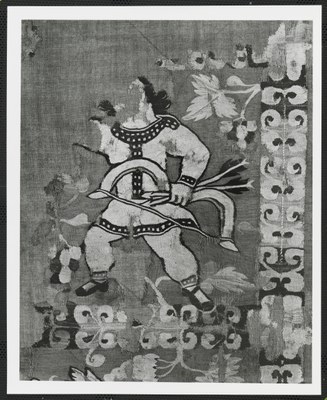

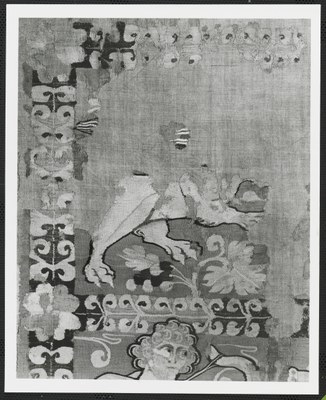

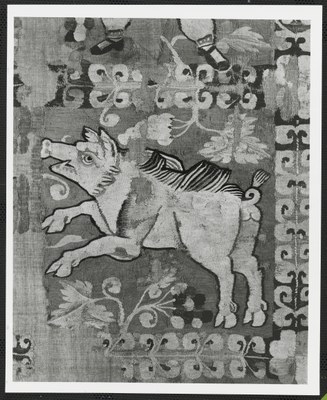

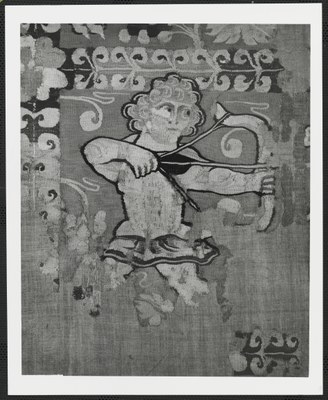

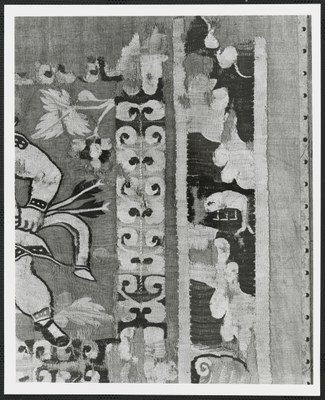

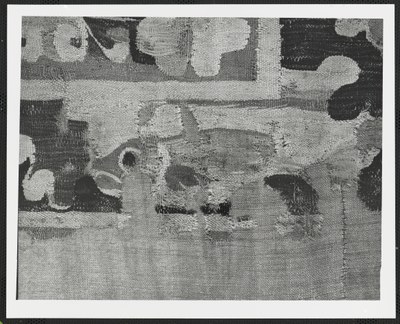

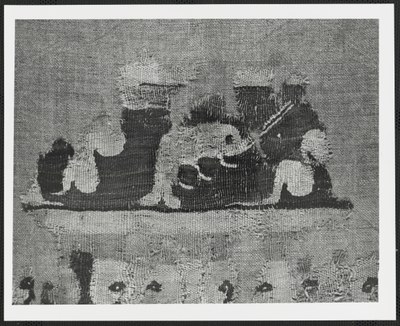

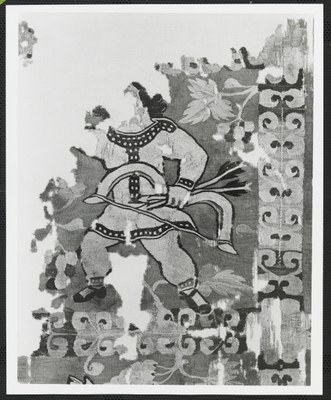

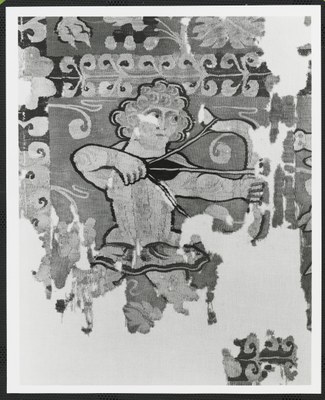

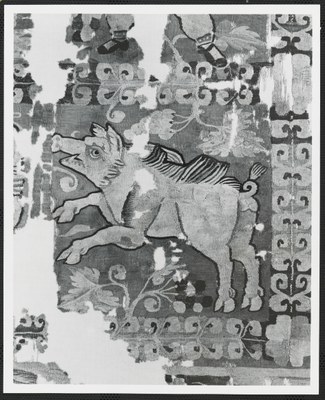

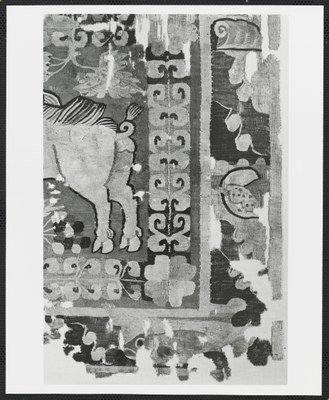

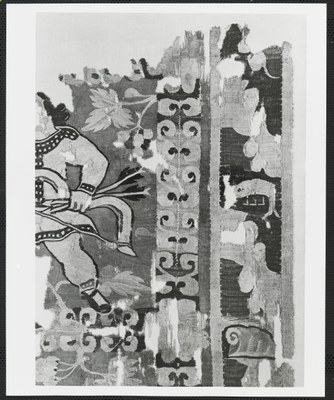

Hunters meet their prey in the two main registers of the extant composition.On boars and lions as favored prey for hunts in the wild, game parks, and circus games, see J. M. C. Toynbee, Animals in Roman Art and Life (London, 1973), chapter 4, “Felines,” 61–90, and chapter 10, “Boars and Pigs,” 131–36. Above, a dark-haired hunter holds his bow and arrow in his lowered left hand and, apparently caught unprepared, stretches out his right arm toward the lion that leaps toward him. Although the center of the lower scene suffered damage and has been reconstructed (see technical analysis), the action of the scene is clear: a light-haired hunter has drawn his bow and aims an arrow at the head of an onrushing boar.

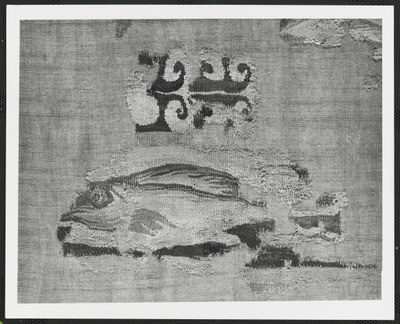

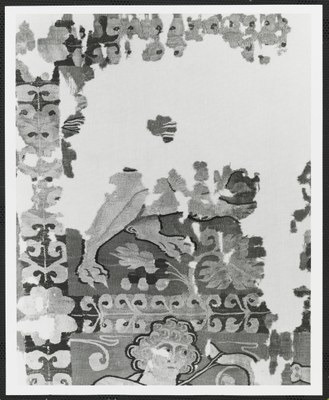

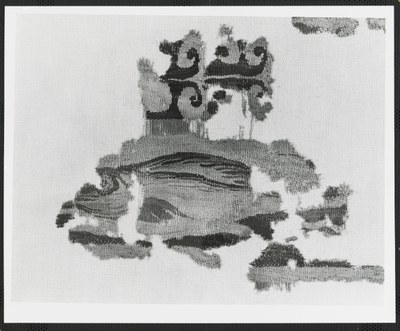

A multipart border frames the two registers. The innermost border of two conjoined rectangles both divides the registers and frames them as the main, inner field of the surviving composition. Each segment of this border is composed of a background of shades of blue over which tan-yellow leaves grow from a single stem in the manner of a garland. At each corner is a four-petalled rosette over a darker blue background. Between this wide, leafy garland and the outer border is a thin strip of red. If this red strip is seen as a continuation of the red background, then the foliage appears at the forefront of the pictorial space. Two thin tan strips frame the wide outer border, which is filled with marine motifs: blue-green seawater and shellfish intermingled with fish and shrimp.

In this weft-faced tapestry weave, the blue wefts of the inner border “read” as green, partly because of optical mixing with the yellowish warp and the use of lighter shades of blue mixed with tan-yellow weft threads. The darker shades of blue used in the outer border are separated by tendrils of (apparently) greenish sea-foam. The green cast would have been given a boost by now-faded yellow dye and by connections to the leafy, fruiting grapevine that, in several places in both of the main fields, emerges from the garland to overlap the contrasting red background.

Strong coloring is integral to the overall effect of the composition. Outlining the hunters and animals in dark blue against bright red lends a three-dimensional effect, sets them apart from the border motifs, and ensures their visibility in low lighting. The coloring inside the outlines is subtle. Counting the number of colors is an impossible task given that some colors of threads were made by spinning together fibers of different colors so as to modulate between different shades and hues; by finely calibrating juxtapositions of yarns of different colors; and by changing yarn dimension (and therefore the “weight” or thickness of line, color intensity, or shadow effects), as is evident in the boar’s forelegs and hooves.

Color passages—whether delicately shaded or composed of lines or blocks of single shades of strong colors—are made by non-horizontal weft passages that curve in the same direction, as the detailed rendering of the boar’s eye and the subtle modeling of the foreshortened knee of the hunter in upper register. These non-horizontal wefts—or eccentric wefts—also produce topographical effects. Weft joins that now gape open, for example, just above the knee, indicate that the textile has been pressed flat. Would the sculptural quality have been more three-dimensional in late antiquity? The weaving of the anatomy of this figure—see the bicep, underarm, and muscled abdomen, for example—and various points all along the outline suggest a kind of relief sculpting of the physique. The treatment of the boar’s brow is even more suggestive of three-dimensional modeling.

The large scale of the piece (which would have been even larger originally; see technical analysis), the lack of surface abrasion, the delicacy of the yarns, and the finely rendered motifs all suggest that the piece is part of a wall-hanging, rather than a covering or rug. The central scenes of hunters facing their prey and the surrounding borders of flora and fauna combine to express an allegorical composition based on the intertwined themes of the virtue fighting vice and life in the natural world. Additional cues suggest that this scene is to be read allegorically rather than realistically. The hunters, for example, are not men, but erotes (cupids from the Latin) or little men (putti in Latin). Although they resemble men in their dress and action, and even in their musculature, they are childlike in their large-headed, short-legged proportions. Like erotes in other iconographic contexts, these hunters are associated with the natural phenomena that surround them and are represented as inhumanly small in relation to the world they inhabit.H. Maguire, “The Good Life,” in Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World, ed. G. W. Bowersock, P. Brown, and O. Grabar (Cambridge, MA, 1999), 239 on the appropriateness of hunting scenes in dining rooms, and 240 on the “profusion of greenery and flowers” with which dining rooms were often decorated. On the proportion of the erotes to vegetation and their association with dew, the Nile, and Ocean, see T. K. Thomas, Late Antique Egyptian Funerary Sculpture: Images for This World and for the Next (Princeton, 2000), 66–67 and 115, notes 9–10. In contrast to motifs representing the natural world and similar to erotes playing at human behavior, the coloring defies a realistic reading of the imagery. The red background, for example, differentiates this symbolic world from the world of men.The motifs of one group of red-ground tapestry hangings are associated with bounty and prosperity; another group features alluring female divinities and nereids. On the latter group, see T. K. Thomas, “The Medium Matters: Reading the Remains of a Late Antique Textile,” in Reading Medieval Images: The Art Historian and the Object, ed. E. Sears and T. K. Thomas (Ann Arbor, 2002), 38–49. On the characterization of red-ground tapestry hangings, see D. Bénazeth and P. Dal-Prà, “Renaissance d’une tapisserie antique,” La Revue du Louvre et des musées de France 45, no. 4 (1995): 29–40, esp. 34.

Together, the borders present one of the myriad of variants in the long-lived tradition of composite images of earthly abundance surrounded by the bountiful ocean.H. Maguire, “The Mantle of Earth,” in “Byzantium and Its Legacy,” special issue, Illinois Classical Studies 12, no. 2 (1987): 221–22, traces the literary tradition back to Homer and explores the late antique pictorial tradition, comparing textiles with mosaics. Numerous examples of mosaics with this imagery from the Hellenistic through the late antique periods—including a clustering of examples from late antique Antioch and other Syrian sites—are illustrated and discussed in K. M. Dunbabin, Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World (Cambridge, 1999), esp. 165, 181–85. In the Nereid tapestry hanging at Dumbarton Oaks (BZ.1932.1), this concept is inverted: a red background is used for a marine setting and is framed by “terrestrial” leafy border with birds.

A close comparison to both the Nereid hanging (with its pearled border, Nereid, and sea monster) and the hunting allegory hanging (with its “oceanic” theme, similar treatment of sea-foam, crustacean legs, and fish) is a border fragment from a red-ground hanging now in Riggisberg at the Abegg-Stiftung.Riggisberg, Abegg-Stiftung, inv. 446: S. Schrenk, Textilien des Mittelmeerraumes aus spätaniker bis frühislamischer Zeit (Riggisberg, 2004), 73–74, no. 17; M.-H. Rutschowscaya, Coptic Fabrics (Paris, 1990), 64 (illustration) and 65 (caption), citing a similar (unspecified) fragment in the Musée de Cluny.

Similar themes on a smaller scale are found on clothing. One comparison for the imagery of a hunter surrounded by a frame of flowers, fruits, birds, and fish is the fine tapestry-woven (wool, silk, and linen) tunic segmentum in Boston.Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 35.87, https://www.mfa.org/collections/object/ornament-for-tunic-tabulae-46155. Likely matches to this segmentum are at the Victoria and Albert Museum, 335-1887, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O93026/tunic-band-unknown/. A textile model painted on papyrus provides another comparison for the hunting scene framed by marine motifs.Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, P. 25759: A. Stauffer, Antike Musterblätter: Wirkkartons aus dem spätantiken und frühbyzantinischen Ägypten (Wiesbaden, 2008), 72, no. 3. For another painted papyrus model of an “oceanic” border for tunic clavi, see 114–15, no. 28. Similar themes are found among floor mosaics as well.H. Maguire, Earth and Ocean: The Terrestrial World in Byzantine Art (University Park, PA, 1987), 69–72; Maguire, “The Mantle of Earth,” 227–28; E. Kitzinger discusses the theme throughout “Studies on Late Antique and Early Byzantine Floor Mosaics: Mosaics at Nikopolis,” DOP 6 (1951): 81–122. In such compositions, this cosmic framing may be seen to comment upon humankind’s combat over the vices, beastly passions that stir the body and soul. Animals as metaphors of human nature are well known in Greco-Roman and Christian culture, from the ancient fables of Aesop (drawn from even more ancient Sumerian and Hebrew proverbs) to medieval retellings of the Physiologus.For the ancient tradition and early developments in Christian late antiquity, see P. Cox, “Origen and the Bestial Soul: A Poetics of Nature,” Vigiliae Christianae 36 (1982): 115–40. Blake Leyerle persuasively interpreted pavement mosaics from this perspective in “Monks and Other Animals,” in The Cultural Turn in Late Ancient Studies: Gender, Asceticism, and Historiography, ed. D. B. Martin and P. C. Miller (Durham, NC, 2005), 150–71. J. M. Schott, Christianity, Empire, and the Making of Religion in Late Antiquity (Philadelphia, 2013), 115, mentions that Constantine interpreted Nebuchadnezzar’s order to throw Daniel in the lion’s den as proof of the “savage, uncivilized character of [Nebudchanezzar’s] mind.” For a broader view, see M. Barasch, “Animal Metaphors of the Messianic Age: Some Ancient Jewish Imagery,” in Approaches to Iconology, ed. H. G. Kippenberg (Leiden, 1985–86), 235–49; and D. Bodi, “Cross-Cultural Transformation of Animal Proverbs (Sumer, Mari, Hebrew Bible, Aramaic Aḥiqar and Aesop’s Fables),” Aliento 6 (2015): 61–112. The Physiologus, likely a late antique text, endured throughout the medieval era: M. J. Curley, trans., Physiologus: A Medieval Book of Nature Lore (Chicago, 2009). Sustained interpretations of late antique hunt and sea imagery, and the combination of hunt, land, and sea motifs, have focused on floor mosaics found in domestic and religious settings.Discussed throughout Leyerle, “Monks and Other Animals,” and Kitzinger “Studies.” See also n4 above. It is conceivable that clothing, furnishings, wall paintings, and mosaic pavements, and even display silver and vessels in other precious materials, could have been seen together as extended allegorical expressions about luxury and morality.

—Thelma K. Thomas, May 2019

Notes

| Accession number | BZ.1937.14 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

7th–9th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (warp) 95 cm × W. (weft) 82.5 cm (37 3/8 × 32 1/2 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool |

| Acquisition history |

Nicholas Tano Collection, Cairo; Paul and Marguerite Mallon Collection, Paris, to 1937 (Marguerite Mallon mentions the tapestry came from “a family in Antioch where it had been for a long time” [letter dated October 25, 1938]); Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, purchase, 1937; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940. |

Hartford, CT, Wadsworth Atheneum, 2000 Years of Tapestry Weaving, December 7, 1951–January 27, 1952.

Baltimore, MD, Baltimore Museum of Art, 2000 of Tapestry Weaving, February 27–March 25, 1952.

Washington, DC, The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Woven Interiors: Furnishing Early Medieval Egypt, August 31, 2019—January 5, 2020.

| Accession number | BZ.1937.14 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

7th–9th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (warp) 95 cm × W. (weft) 82.5 cm (37 3/8 × 32 1/2 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool |

| Acquisition history |

Nicholas Tano Collection, Cairo; Paul and Marguerite Mallon Collection, Paris, to 1937 (Marguerite Mallon mentions the tapestry came from “a family in Antioch where it had been for a long time” [letter dated October 25, 1938]); Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, purchase, 1937; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940. |

F. Morris, “Catalogue of Textile Fabrics, The Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1940), 79–83.

2000 Years of Tapestry Weaving (Hartford, CT, 1951), no. 14.

A. C. Weibel, Two Thousand Years of Textiles: The Figured Textiles of Europe and the Near East (New York, 1952), no. 15.

Dumbarton Oaks, The Dumbarton Oaks Collection, Harvard University: Handbook (Washington, DC, 1955), 154, no. 300.

J. Beckwith, “Coptic Textiles” CIBA Review 133 (1959).

K. Wessel, Koptische Kunst: Die Spätantike in Ägypten (Recklinghausen, 1963), 213–24, fig. 133.

K. Wessel, Coptic Art, trans. J. Carroll and S. Hatton (New York, 1965), 201, fig. 133.

Dumbarton Oaks, Handbook of the Byzantine Collection (Washington, DC, 1967), 108, no. 363.

D. Thompson, “Catalogue of Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1976), no. 48.

D. Thompson, “New Technical and Iconographical Observations about Important Coptic Hangings with Marine Hunting Themes (1),” BullCIETA 54, no. 2 (1981): 63–81; fig. 1.

M.-H. Rutschowscaya, Coptic Fabrics (Paris, 1990), 64–65.

G. Bühl, S. Krody, E. Dospěl Williams, Woven Interiors: Furnishing Early Medieval Egypt (Washington, DC, 2019), 42-3, no. 10.

| Accession number | BZ.1937.14 |

|---|---|

| Attribution and Date |

Egypt,

7th–9th c.

|

| Measurements |

H. (warp) 95 cm × W. (weft) 82.5 cm (37 3/8 × 32 1/2 in.) |

| Technique and Material |

Tapestry weave in polychrome wool |

| Acquisition history |

Nicholas Tano Collection, Cairo; Paul and Marguerite Mallon Collection, Paris, to 1937 (Marguerite Mallon mentions the tapestry came from “a family in Antioch where it had been for a long time” [letter dated October 25, 1938]); Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss, purchase, 1937; Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 1940. |