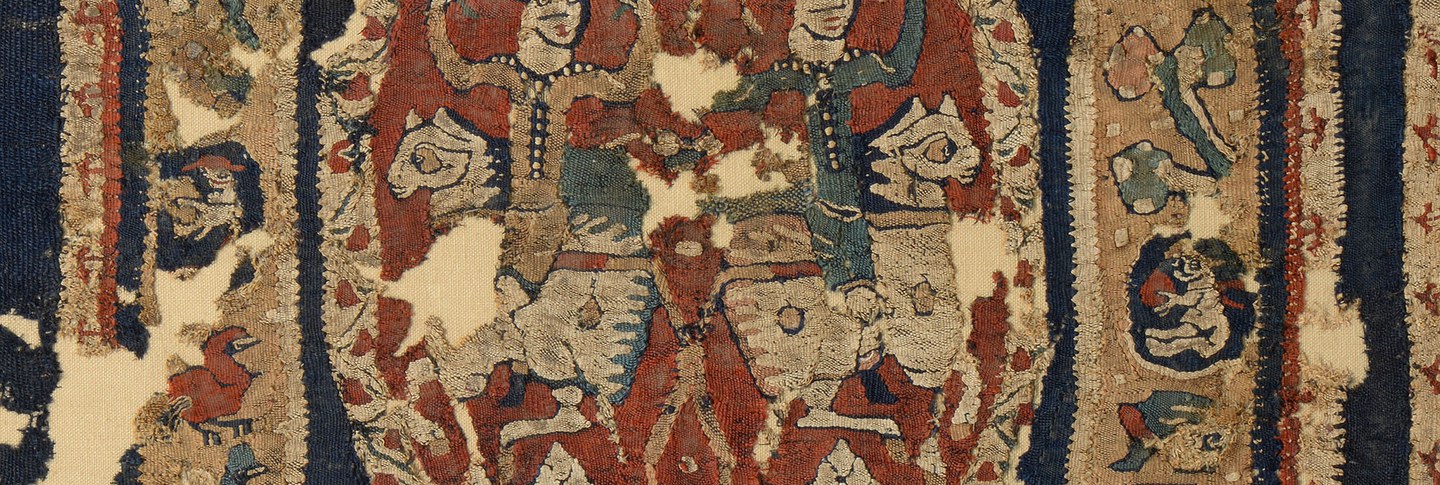

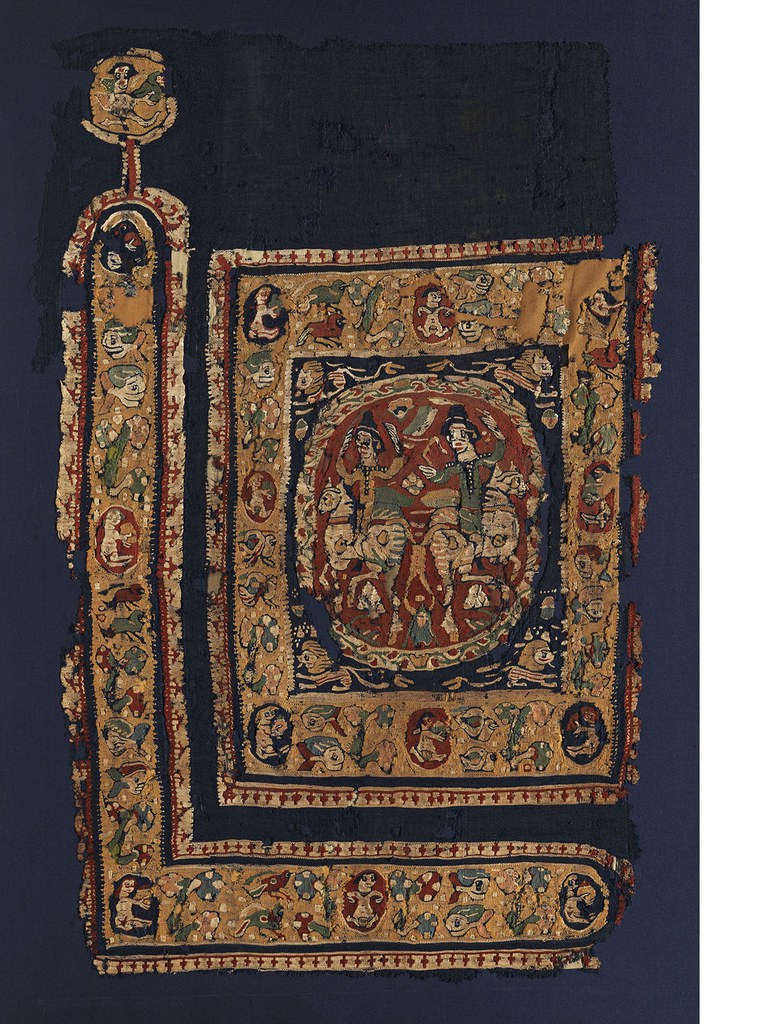

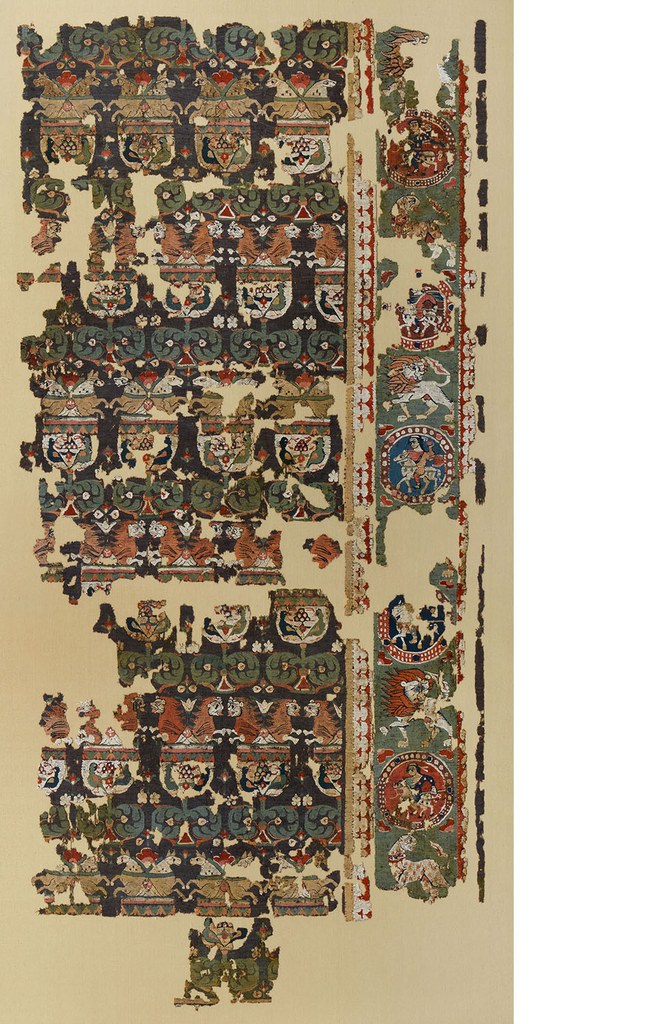

A large fragmentary textile from Dumbarton Oaks that presents two horsemen in a medallion as its central focus speaks to both the riches of its elite owner in late antique Egypt and the desires of modern collectors (BZ.1943.8, fig. 1).Washington, DC, Dumbarton Oaks, BZ.1943.8, https://www.doaks.org/resources/textiles/catalogue/BZ.1943.8. The fragment, over one meter in height, is made of linen and dark blue wool.The piece measures 102.5 centimeters in height and 77.0 centimeters in width (40 3/8 × 30 5/16 in.). The addorsed mounted horsemen within the medallion wear fitted caps, boots, and knee-length garments festooned with pearls (fig. 2). Surrounding this primary design is a rectangular border occupied by eight putti, each in its own oval frame, separated by groups of motifs referring to the bounty of the earth: food, fish, plants, and birds (figs. 3–4). Lions appear in the spandrels between the central medallion and its rectangular border; they face outward toward the border as if protecting the horsemen, a posture appropriate for a textile that itself may have been hung to shield or protect people from view (fig. 5). The fragment was originally the lower right corner of a hanging, possibly a curtain, as indicated by the gammadion (L-shape) with circular finials at each end, which frames the lower right corner of the fragment. This element is filled with the same putti, flora, and fauna found in the rectangle above. In the middle of the horizontal arm of the gammadion stands a putto with arms nearly akimbo, facing the viewer and, perhaps, dancing. Small red T-shapes decorate the border of the medallion and gammadion: some of these look like arrows, some like crosses, and some like capital Ts (fig. 6).

Iconographic and comparative evidence, discussed below, indicate that this textile should be dated to the seventh to eighth century, a politically tumultuous period in Egypt when the local population was variously under Byzantine (twice), Persian, and Arab rule. Scholars have often ignored the seventh to ninth centuries when examining textiles and works in other media, perhaps in part because of the difficulties in understanding the cultural complexity in Egypt during this time. Furthermore, as textiles entered museum and private collections in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, they were often assumed to predate the early seventh century, an assumption based largely on their figurative motifs, despite the lack of archaeological context or scientific evidence to support such dating. The tendency to argue for continuity with the Roman world in regard to textile manufacture, use, and iconography has been particularly entrenched in scholarly thought until recently. That is, textiles have been imagined anachronistically in Roman houses with iconography relating to Roman magic and religion. For example, James Trilling’s 1982 study, The Roman Heritage: Textiles from Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean, 300 to 600 AD, as the title indicates, examines textiles based on their perceived Romanness.J. Trilling, The Roman Heritage: Textiles from Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean, 300 to 600 AD (Washington, DC, 1982). Sometimes this Roman lens is called for by a secure date or archaeological context. But typically, the contexts are unclear, if they exist at all, as is the case with the Dumbarton Oaks textile that is the subject of this essay. For another example of textile scholarship from this Roman perspective, see E. D. Maguire, H. P. Maguire, and M. J. Duncan-Flowers, Art and Holy Powers in the Early Christian House (Urbana, IL, 1989). This, however, becomes a problem when textiles are redated later. The range of possible uses and the reception of textiles in later late antique (seventh- and eighth-century) Egypt was not limited to Roman sources.

In the last decade, an important shift in the Romanocentric line of inquiry has taken hold, notably with many of my colleagues in this volume. Helen Evans and Brandie Ratliff’s 2012 exhibition Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition showed how Sassanian Persia and later, Islam, far from being mere influences on Byzantine art, were intertwined economically, culturally and geographically with the Byzantines, stemming from their having the same ancient cultural referents and sometimes occupying the same lands in succession.H. C. Evans and B. Ratliff, eds., Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 7th–9th Century (New York, 2012), with contributions by T. K. Thomas, C. Fluck, and K. Colburn. In Clothing the House, Cäcilia Fluck and Antoine De Moor present the interconnectedness of cultures from the Near East and across the Mediterranean, with regard to textile terminology and the presentation of textiles in works of art and in architecture.A. De Moor and C. Fluck, eds., Clothing the House: Furnishing Textiles of the 1st Millennium AD from Egypt and Neighbouring Countries; Proceedings of the 5th Conference of the Research Group “Textiles from the Nile Valley,” Antwerp, 6–7 October 2007 (Tielt, 2009). Matthew P. Canepa’s work has illuminated cross-cultural interactions from the point of view of Sassanian Iran.See M. P. Canepa, “Textiles and Elite Tastes between the Mediterranean, Iran and Asia at the End of Antiquity,” in Global Textile Encounters, ed. M.-L. Nosch, F. Zhao, and L. Varadarajan (Oxford, 2014), 1–14, and idem, “Distant Displays of Power: Understanding Cross-Cultural Interaction among the Elites of Rome, Sasanian Iran, and Sui-Tang China,” in “Theorizing Cross-Cultural Interaction among the Ancient and Early Medieval Mediterranean, Near East and Asia,” special issue, Ars Orientalis 38 (2010): 121–54. However, despite the excellent work of these scholars, the Romanocentric view of textiles in late antiquity still persists.

Redating the Dumbarton Oaks hanging to the seventh to eighth century—that is, the time of the Arab conquest and just after—provides an opportunity to refocus our lens on this period and explore the changes occurring in the use of textiles in domestic interiors, sharpening our understanding of this and other textiles beyond the rubric of Romanness.For similar issues in Umayyad textiles, see E. Dospěl Williams, “A Taste for Textiles: Designing Umayyad and Early ʿAbbāsid Interiors” and A. Shalem, “‘The Nation Has Put On Garments of Blood’: An Early Islamic Red Silken Tapestry in Split,” in the present volume. While I am cognizant that we cannot be certain whether this textile was utilized in a home belonging to a Muslim, Jew, or Christian, or whether the original owner understood Greco-Roman, Arab, or other cultural references, I wish to push past our reliance on thinking of use, iconography, and domestic space only in terms of our knowledge of late Roman culture and Greco-Roman religious sources. Rather, it is useful to think, at least in cases like this, in terms of the customs and habits of those later late antique peoples of Egypt and their homes. In this essay, I will begin with a reconstruction of the object based on archaeological, pictorial, and written evidence. I will then turn to the question of the textile’s date, outlining the evidence that will allow me to rehang this fragment in a home in Arab-ruled Egypt in the seventh to eighth century. I will also discuss the building of textile collections in the early twentieth century and how it affected the categorization and study of textiles.

Reconstructing the Fragment as a Hanging

Technical Evidence

This object is a fragment of a larger textile, once likely part of the lower-right corner of a larger piece, as suggested by the framing gammadion. The motifs, which include standing figures and animals, are all arranged vertically with their heads oriented in the same direction, suggesting a vertical orientation for the fragment when it was installed. It cannot be ruled out that when the piece was complete, now missing elements of the composition could have been oriented horizontally. There is, however, additional evidence to indicate that the fragment was intended to be viewed hanging vertically (as opposed to lying on a floor or draped over furniture), namely its weight, its dimensions, a lack of wear in a pattern associated with horizontal placement, the weaving technique, and, finally, the likelihood that it was part of a pair.

The textile was therefore likely a curtain or hanging. Curtains and hangings had several uses in late antique interiors beyond decoration: they divided space or blocked views or passage within an interior, or between inside and outside, and heavier-weight examples provided insulation. The Dumbarton Oaks fragment is lightweight, suggesting that it could be easily pulled back and tied as a curtain would be, and that it was not sturdy enough to carpet a floor. Tablecloths tend to be thin and beds could also be covered with thin textiles, though many have loop pile to add warmth for the sleeper.See, for example, the linen and wool cover or blanket attributed to third- to fifth-century Egypt in New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 90.5.899, https://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/444372. But the probable large size of the full textile argues against it covering a table or bed. We can imagine from other examples (figs. 12, 22) that the original height was at least double that of the remaining fragment (102.5 cm), which would mean that it was nearly seven feet tall. Surviving hangings and curtains are often of this scale, such as a nearly intact hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, to be discussed later (fig. 22), that measures over eight feet long, a length that would overwhelm most furniture.New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.9.3 (265.5 × 162.7 cm), https://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/448227. The dimensions of another curtain are mentioned in the Cairo Geniza: 5.5 × 3 cubits (about 8 1/4 × 4 1/2 feet). For a study and translation of a large portion of the Cairo Geniza, see S. D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza (Berkeley, CA, 1967–93). The dimensions mentioned in the Cairo Geniza are cited in G. D. Anderson, The Islamic Villa in Early Medieval Iberia: Architecture and Court Culture in Umayyad Córdoba (Farnham, UK, 2013), 88n64. While some wear exists, and subsequent repairs are present, the textile fragment does not exhibit abrasions associated with horizontal placement or use as a tablecloth: it does not appear to have been walked on, it does not have creases that would indicate it was draped over a piece of furniture, it lacks stains concentrated in one area suggesting a single area of exposure, and it lacks obvious food-derived stains.

The back of the Dumbarton Oaks fragment cannot be studied because it is mounted and unable to be safely removed from its backing. However, the design of a small fragment possibly separated from our larger piece can be read equally well from the front and the back (fig. 7).Washington, DC, Dumbarton Oaks, BZ.1943.8a, https://www.doaks.org/resources/textiles/catalogue/BZ.1943.8a. Conservator Kathrin Colburn’s analysis of the small fragment has found that the weaving has a few weft threads showing on the reverse side where the weaver skipped warps, so that the back and front can be properly determined (though not easily) by the naked eye. While we cannot definitively extrapolate from the back of the small piece to the larger whole of which it was likely once a part, there is no reason to imagine that the weaver changed to a less efficient form of weaving for other parts of the textile. This legibility points to the technical achievement of the weaver, who economized on thread rather than leaving unused ends of thread hanging off the reverse, as one sometimes sees in tapestry-woven fragments (fig. 8). It also ensured that the textile could be hung in a doorway or used to divide a room and be enjoyed by viewers on either side of it. It is unfortunate that the top of the textile is missing, as it likely would have provided information regarding how it was fastened or hung, whether by rod, hooks, or rings (figs. 9–10).See K. Colburn, “Loops, Tabs, and Reinforced Edges: Evidence for Textiles as Architectural Elements,” in this volume. Nevertheless, the piece’s weight, the regular wear it exhibits, and the probability that its reverse side is free of hanging threads help us to imagine the textile on a wall or between columns in a tony interior.

Another factor suggesting that it was a curtain or part of a set of hangings is the nearly identical piece at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem (fig. 11). In 2013, Elizabeth Dospěl Williams visually inspected the Israel Museum piece and measured various design elements, which are nearly identical to the measurements taken by Colburn in her analysis.The suggestion that these textiles are from a set was made in A. Baginski and A. Tidhar, Textiles from Egypt, 4th–13th Centuries C.E. (Jerusalem, 1980), no. 191. I have not examined the Israel Museum piece in person and am very grateful to Elizabeth Dospěl Williams for sharing her photographs and complete documentation of her visit to the Israel Museum. The Israel Museum piece is smaller in overall dimensions due to losses or cuts made to the textile around the decoration at some point in its history, but the gammadion and the tabula with the rider are nearly identical in size, strongly suggesting that they were once part of the same textile or set of textiles, possibly a group of curtains or hangings (table below).

|

Measurement |

Dumbarton Oaks Textile (BZ.1943.8) |

Israel Museum Textile (925.70) |

|

Height (warp direction) |

102.5 cm |

Measurement unknown |

|

Width (weft direction) |

77.0 cm |

Measurement unknown |

|

Gammadia (incl. roundels) |

96.0 × 70.0 cm |

97.0 × 58.6 cm (roundel missing on right side) |

|

Center tabula |

58.0 × 45.0 cm |

59.4 × 47.5 cm |

|

Inner tabula |

37.0 × 29.0 cm |

Measurement unknown |

|

Center medallion |

31.5 × 25.5 cm |

Measurement unknown |

|

Upper roundel |

10.0 × 9.5 cm |

10.2 cm high |

|

Lower roundel |

10.0 × 9.0 cm |

Missing |

Pictorial Evidence

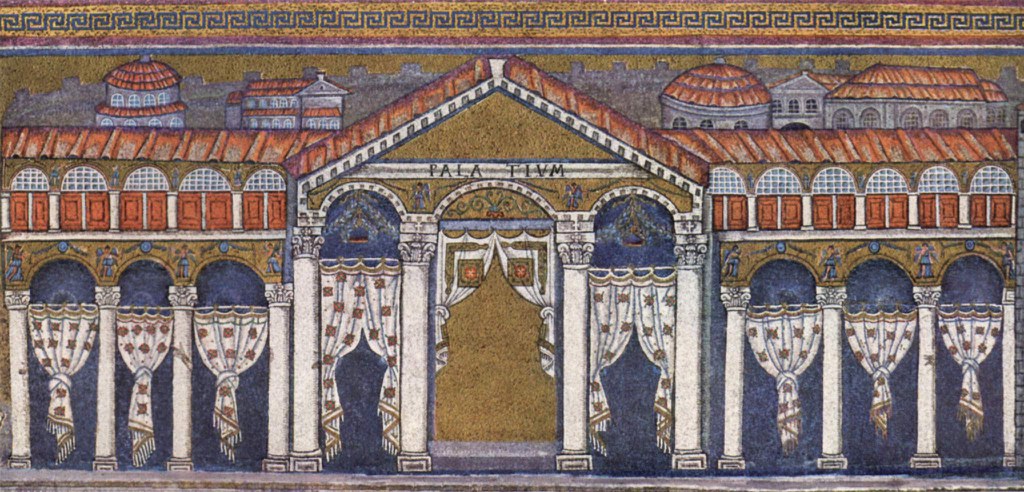

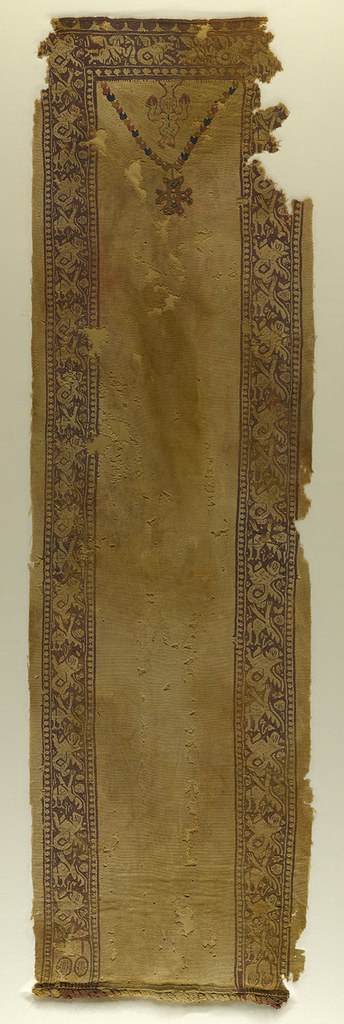

It is possible that at one time the fragments at Dumbarton Oaks and the Israel Museum were part of a single textile, arranged either side by side or one on top of the other. The edges of the surviving fragments do not confirm or deny that they were divided. Testing of dyes and/or analysis under a microscope have yet to be executed to establish any relationship between them. Still, the piece belonging to the Israel Museum appears to be the left hand to the Dumbarton Oaks piece’s right, as the framing gammadion is on the lower left, opposite to the Dumbarton Oaks piece. The visual record attests that curtains and hangings were often hung in sets. Moreover, the gammadion is a common framing device, seen on clothing and on wall hangings or curtains (fig. 12).

The pictorial record provides evidence for the presence of hangings and curtains in many regions around the Mediterranean, where they were used to enliven interiors and for more pragmatic purposes. Most famously, the sixth-century mosaic in the church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna displays a series of intercolumnar curtains decorating the façade of Theodoric’s palace; the set of curtains depicted in the center of the palace, where its doorway would be, has a gammadion framing device much like the Dumbarton Oaks piece (fig. 13). Because I am dating the Dumbarton Oaks hanging to the seventh to eighth centuries, it is appropriate to look at later Byzantine and Umayyad evidence as well. Maria Parani has shown that almost no curtains appear in the written record or archaeological remains of the middle Byzantine Empire (eighth–twelfth centuries), making it more likely that it was used, if not made, in Egypt, outside of the Byzantine world.M. Parani, “Curtains in the Middle and Late Byzantine House,” in this volume. It therefore seems appropriate to look beyond Byzantium for comparanda. Contemporary with our fragment, the Umayyad bathhouse at Quṣayr ʿAmra in Jordan, dating to the early eighth century, has frescoes depicting bathers before a closed curtain, presumably giving them privacy (fig. 14). Umayyad decorative practices continued in tenth-century Spain; Glaire Anderson hypothesizes that the main hall at the villa al-Rummāniyya outside of Córdoba, for instance, incorporated diplomatically strategic decoration in the form of curtains and hangings. These pieces orchestrated the vision and movement of visitors and displayed insignia of Umayyad sovereignty, a practice that Anderson describes as widespread across North Africa and into the Near East (fig. 15).Anderson discusses the prominence of textiles in these spaces and has created digital reconstructions that include textiles: Anderson, Islamic Villa, 87–88 and figs. 16–17. Depictions of hangings and curtains in church interiors in Egypt, most of which predate our textile, are not uncommon; the newly cleaned paintings at the church of St. Pshoi at the Red Monastery near Sohag, Egypt, include fictive curtains decorating the second register of niches, mimicking the use of real textiles in such spaces (fig. 16).J. Ball, “Textiles: The Emergence of a Christian Identity in Cloth,” in The Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art, ed. R. Jensen and M. Ellison (London, 2018); E. S. Bolman, The Red Monastery Church: Beauty and Asceticism in Upper Egypt (New Haven, 2016).

A church setting for the Dumbarton Oaks textile seems unlikely given its imagery. A palatial setting also seems unlikely, given that it is made of wool and linen rather than silk, and lacks any royal insignia. We can, however, easily imagine the Dumbarton Oaks textile hanging inside an elite home, being drawn by servants to cordon off private space—a concept that developed in later late antiquity—whenever guests gathered for dining or business.

Collecting Textiles in the Twentieth Century

It is interesting to consider not only why twentieth-century collectors were attracted to late antique textiles, but also how they acquired them, as both narratives factor into the present interpretation. When vast quantities of late antique textiles were discovered suddenly beginning in the late nineteenth century, archaeological methods were looser than today’s standards. Because these finds were not well documented, details of context, evidence for dating, and provenance are still missing for works acquired before the mid-twentieth century. The textiles excavated in this flurry of activity were deemed “Coptic,” a term that strictly speaking is used to describe the last phase of the Egyptian language spoken in late antiquity by people in Egypt, and is also the name for the Monophysite branch of Orthodox Christianity that dominated there.For a full discussion of the term “Coptic” and the history of the archaeology of textiles, see A. Stauffer, Textiles of Late Antiquity (New York, 1995), and T. K. Thomas, “Coptic and Byzantine Textiles Found in Egypt: Corpora, Collections, and Scholarly Perspectives,” in Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700, ed. R. S. Bagnall (New York, 2007), 137–62. The term is also commonly applied to the period of time when Egypt was under Byzantine Christian rule, from the fourth to the seventh century. For their part, modern textile historians have often used the term “Coptic” to denote a woven textile of wool or linen, typically with figurative motifs alongside floral and geometric ones. Loosely, the word is also used to denote a more abstract, heavily outlined style in contrast to a perceived Roman naturalism. The textiles thus classified as “Coptic” often moved rapidly from the ground into collections during the nineteenth century, with the archaeologists serving as dealers in many cases.Archaeologist Robert Forrer, for example, sold 1,200 textiles to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1899: “Dr Robert Forrer,” V&A Archives, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/d/dr-robert-forrer-1866-1947. Elisabeth O’Connell describes the bustling art market surrounding nineteenth-century Akhmīm: E. R. O’Connell, “Representation and Self-Presentation in Late Antique Egypt: ‘Coptic’ Textiles in the British Museum,” in Textiles as Cultural Expressions: Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America, September 24–27, 2008, Honolulu, Hawaii, http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/236. Moreover, while many of these textiles were found in Egypt, in many cases they or their raw materials were imported from around the Mediterranean and the Near East.The importance of textile archaeology as a specialized field for processing and analyzing such finds cannot be overstated. For more on the field and the complexities of determining manufacture of textiles, see J. P. Wild, Textiles in Archaeology (Aylesbury, UK, 1988), and S. Schrenk, ed., Textiles in Situ: Their Find Spots in Egypt and Neighbouring Countries in the First Millennium CE (Riggisberg, 2006). For an understanding of scientific methods of textile archaeology and the state of the field through the massive finds at Antinoopolis (mod. Shaykh ʿIbādah, Egypt), see Y. Lintz and M. Coudert, eds., Antinoé: Momies, textiles, céramiques et autres antiques; Envois de l’État et dépôts du musée du Louvre de 1901 à nos jours (Paris, 2013). This excavation site demonstrates that textiles found in Egypt came from a variety of regions, in and outside of Egypt.

The influx of textiles into so many museums and private collections coincided with an interest among artists, designers, and collectors in the so-called primitive arts, which they saw as inspiration for modern art movements. Kostis Kourelis, in examining the beginnings of modern archaeology in Greece, describes a circle of intellectuals and artists who had their feet in both the Byzantine past and the avant-garde present. Kourelis points out the close connections between modernism and Byzantium, citing the 1931 Exposition internationale d’art byzantin in Paris, in which Byzantine objects were “unequivocally conflated with the aesthetics of modern art.”K. Kourelis, “Byzantium and the Avant-Garde: Excavations at Corinth, 1920s–1930s,” Hesperia 76, no. 2 (2007): 391–442 (quote at 392). A contemporary reviewer of the exposition compared the exhibited textiles with the work of artists André Derain, Henri Matisse, and Raoul Dufy. Matisse had an extensive collection of textiles, many of which appear in his paintings.The 2017 exhibition Matisse in the Studio at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, beautifully illustrated the link between the material of late antique Egypt and modernist artistic developments. E. McBreen and H. Burnham, Matisse in the Studio (Boston, 2017). Rose Choron, who began collecting in the 1950s, referred to the textiles as “her own Picassos and Klees.”E. D. Maguire, Weavings from Roman, Byzantine and Islamic Egypt: The Rich Life and the Dance (Champaign, IL, 1999), 6.

Many institutional collections of textiles were built not only to educate the public about late antiquity but also to inspire modern design. In 1929, Brooklyn Museum curator Stewart Culin created an exhibition that included textiles from the collection of the Pratt Institute, a well-known art school, alongside other ancient objects of interest to designers and artists, describing his intention that the exhibition be “useful to students of textiles and designers who are looking for inspiration from original sources of patterns and motifs. . . . They are considered valuable and exhibited not so much for the weaving which in itself is of interest to textile students, but for the remarkably beautiful designs which were produced in those days and for the glorious color that has persisted for nearly 2000 years.”Brooklyn Museum archives, Press Releases, 1916–30 (01–03/1929), cited in E. Bleiberg, “Collecting and Exhibiting Late Antique Textiles at the Brooklyn Museum,” in Designing Identity: The Power of Textiles in Late Antiquity, ed. T. K. Thomas (Princeton, NJ, 2016), 99. The interest in the “primitive” aesthetic led to an increased demand for textiles among dealers and collectors; unfortunately, as with the Dumbarton Oaks example, textiles were often cut to feature designs that catered to modern tastes.Textiles were sometimes cut to save the clean parts and throw away soiled parts, but there is no question that figural, floral, and geometric motifs are often centered in fragments, as with Dumbarton Oaks’ textile, implying that they were cut to feature the design.

Many of the textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks collection were brought together by Robert Woods and Mildred Barnes Bliss in the 1920s and 1930s, which has been termed a “golden age” for textiles.Lise Bender-Jørgensen discusses the major advances in textile archaeology during the 1920s and 1930s due in part to the extraordinary number of textiles coming into circulation for study: L. Bender-Jørgensen, “The World According to Textiles,” in Ancient Textiles: Production, Craft and Society; Proceedings of the First International Conference on Ancient Textiles, Held at Lund, Sweden, and Copenhagen, Denmark, on March 19–23, 2003, ed. C. Gillis and M.-L. B. Nosch (Oxford, 2007), 7–12. The history of textiles in the Bliss collection can be found in G. Bühl and E. Williams, “Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection: Past Studies and Future Directions,” in Textiles, Tools and Techniques of the 1st Millennium AD from Egypt and Neighbouring Countries: Proceedings of the 8th Conference of the Research Group “Textiles from the Nile Valley,” Antwerp, 4–6 October 2013, ed. A. De Moor, C. Fluck, and P. Linscheid (Tielt, 2015), 62–69, and E. Dospěl Williams, “Minor Art, Major Works: An Overview of Dumbarton Oaks’ Collections of the Late Antique and Medieval Textiles,” in Thomas, Designing Identity, 104–15. Their passionate collecting of textiles, including Pre-Columbian and late antique specimens, coincided with their amassing one of the most significant assemblages of Byzantine artifacts in the world. Elizabeth Dospěl Williams points out that while they consulted with textile experts, they collected with an eye toward the eventual display of their acquisitions at Dumbarton Oaks, rather than focusing solely on historical and educational value.Dospěl Williams, “Minor Art, Major Works,” 107. These textiles were thus transplanted across space and time from the rich interiors of late antique households to a rich interior of the modern world, Dumbarton Oaks. The hanging at the center of the present study came into the museum in the 1940s, a few years after the Blisses’ donation of their property and collection to Harvard University. Although they were not themselves responsible for the acquisition of the hanging with riders, this piece perfectly complemented and strengthened the Blisses’ original collection of large, high-quality textiles, many of which had likely been furnishing textiles.Ibid., 106.

Unfortunately, we know little about why this particular textile was acquired by Dumbarton Oaks in September 1943 from the Byzantine Institute in Massachusetts.For a history of the Byzantine Institute and its relationship to Dumbarton Oaks, see “The Byzantine Institute and Dumbarton Oaks Fieldwork Records and Papers,” ca. late 1920s–2000s, MS.BZ.004, Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC, https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/16/resources/709. According to correspondence between Thomas Whittemore, who had founded the Byzantine Institute in 1930, and Edward W. Forbes, director of the Fogg Art Museum between 1909 and 1944 and a contributor to Whittemore’s conservation projects, the piece was found in Antinoopolis (modern-day Shaykh ʿIbādah, Egypt).As per telegram from Whittemore to Forbes, cited in communication between P. W. Mason and John Thacher, December 16, 1943, Byzantine Institute and Dumbarton Oaks Fieldwork Records and Papers. Whittemore, who worked on excavations in Egypt throughout the 1910s and 1920s, does not indicate whether he found the piece himself, purchased it through a dealer, or got it through other means, so the provenance is impossible to determine. In any case, this hanging is a prime example of how Dumbarton Oaks was able to continue building its collection after the Blisses’ time.

Evidence for the Location of Manufacture

Because the Dumbarton Oaks hanging was possibly though by no means definitively found in Egypt, an examination of textile manufacturing within Egypt is necessary. The provenance for the matching curtain at the Israel Museum is even murkier than the vague attribution to Egypt for the Dumbarton Oaks textile: it can only be traced to an unnamed dealer in Milan.Thanks to Elizabeth Dospěl Williams, who unearthed this information in the file for this object during her July 2013 trip to the Israel Museum. Historical accounts suggest that Egypt was known far and wide for its textiles. The first-century Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, which describes the goods deriving from each port along the Egyptian coast, includes numerous mentions of high-quality furnishing and dress textiles.F. J. L. Handley, “‘I Have Bought Cloth for You and Will Deliver It Myself’: Using Documentary Sources in the Analysis of the Archaeological Textile Finds from Quseir al-Qadim, Egypt,” in Textiles and Text: Re-Establishing the Links between Archival and Object-Based Research; Postprints, ed. M. Hayward and E. Kramer (London, 2007), 10–17. Egypt’s textile industry and the fame of its exports continued in the Middle Ages. A dubious story in al-Bayhaqī’s tenth-century al-Maḥāsin wa’l-masāwī about the origin of ṭirāz describes Egypt’s reputation in Baghdad, especially for curtains: “What a very disagreeable thing it is for the faith and Islam, that this [a ṭirāz inscription] should be stamped on the paper and that it should be borne on the pottery, and garments, which, both, are made in Egypt, and the other things made in that country, such as curtains (sutūr), etc., which bear the ṭirāz on account of its (Egypt’s) extent and abundant wealth.”R. B. Serjeant, “Material for a History of Islamic Textiles up to the Mongol Conquest,” Ars Islamica 9 (1942): 66, among other examples of Egypt’s reputation for curtains that Serjeant cites. Indeed, Egypt’s most profitable exports were its textiles.G. Frantz-Murphy, “A New Interpretation of the Economic History of Medieval Egypt: The Role of the Textile Industry, 254–567/868–1171,” Journal of the Economic History of the Orient 24, no. 3 (1981): 274–97. For a comparison of the exporting of textiles in the Roman period with later Mamlūk Egypt, see Handley, “‘I Have Bought Cloth.’”

Textiles found in Egypt were, of course, not necessarily manufactured there. Studies of the textile industry in Egypt illustrate clearly that the long-distance textile trade boomed from late antiquity well into the Mamlūk period and beyond.In addition to Handley’s study, the Cairo Geniza documents show this most clearly: Goitein, Mediterranean Society. Many finds in Egypt were traded goods rather than locally made ones, and thus technique and iconography are often insufficient indicators of a textile’s origins, although for many textiles they are the only information remaining.Having only iconographical information with which to attribute a textile was certainly a problem in the nineteenth and early twentieth century; see, e.g., W. F. Volbach and E. Kühnel, Late Antique, Coptic and Islamic Textiles of Egypt (London, 1926). Even in studies today this remains a problem, as discussed in Thomas, “Coptic and Byzantine Textiles.” The condition of the Dumbarton Oaks hanging, with its still-saturated colors and few losses (apart from it being a fragment of a larger hanging), suggests that it was well cared for, was displayed vertically, and was perhaps used in a dry environment, such as Egypt. The techniques and the motifs represented, which are unusual in combination, are also consistent with Egyptian manufacture, and allow us to attribute and date the piece more securely, albeit cautiously.Kathrin Colburn has noted in personal discussions that the piece has S-spun thread. S-spun thread is typically associated with textiles of Egypt, while Z-spun is associated with Persian manufacture; A. De Moor, M. Van Strydonck, and C. Verhecken-Lammens, “Radiocarbon Dating of Two Sasanian Coats and Three Post-Sasanian Tapestries,” in Riding Costume in Egypt: Origin and Appearance, ed. C. Fluck and G. Vogelsang-Eastwood (Leiden, 2004), 181–87.

Dating and Attribution via Iconography

The motifs ornamenting the Dumbarton Oaks textile probably conjured many stories and beliefs for its viewing audience, and various meanings were likely intended. In later late antiquity, a mixing of iconographic elements is common, and one can find references to multiple traditions—such as Nilotic imagery, classical mythology, Christianity, and Persian culture—in a single work.Cäcilia Fluck notes, for instance, the mingling of elements of Roman and Persian dress in single garments: C. Fluck, “Dress Styles from Syria to Libya,” in Evans and Ratliff, Byzantium and Islam, 160. For example, a tunic panel at the Brooklyn Museum, originally intended for the front of the torso, has ornamentation imitating a pendant Christian cross on a beaded string and a dancing maenad pendant common to Dionysian imagery, in addition to clavi populated with a series of Persian griffins and Hellenic putti in flight (fig. 17).T. K. Thomas, “Material Meaning in Late Antiquity,” in Thomas, Designing Identity, 48; Ball, “Textiles: The Emergence of a Christian Identity in Cloth,” 221.

Before attempting to understand the mélange of imagery on the Dumbarton Oaks piece, it is useful to imagine it in its original context. As discussed above, I am proposing that this textile was a hanging—probably one of a pair of curtains—intended for an elite home. The textile may have served as a barrier, hanging in a liminal space between rooms or dividing a room, thus barring the viewer’s access to another part of the interior. Approaching the space where it hung, its viewers would have been able to see the riders even from a distance, as they are approximately a foot tall on their own. Many of the textile’s details, however, would have been visible only upon close inspection. As many of the motifs are commonly found on other textiles (although not typically represented together on the same textile), the viewer may have been able to recall similar compositions of flora and fauna as they approached the textile, even if the details were not yet sharp. I argue that the specific meanings of the lions, for example, or the birds, were less important than the overall message of prosperity, and that the hypothetical viewer’s interpretation may have been fluid. Together, these motifs represent an aspirational message of abundance, and the rich interior in which the textile hung would have confirmed the wealth of the homeowner. Some aspects of the design also suggest a protective purpose, subtly guarding against viewers moving beyond the curtain.

Equestrian Figures

As horse-and-rider images are ubiquitous in all media across the late antique and medieval world, both East and West, any iconographic analysis of their presence on the Dumbarton Oaks fragment might seem so broad an approach as to be unproductive. Scholars have spent a great deal of time categorizing equestrian imagery in an attempt to understand its sources. These images include the imperial horse and rider in the adventus scenes of the Roman period, in which a victorious emperor or other leader rides through a gate into a city, often holding a weapon and/or shield; the haloed rider, a Christian saintly figure who defends against the devil; the hunter-rider with bow drawn, aiming at animals underfoot (typically lions, rabbits, or deer), which derives from Sassanian art; and so on (figs. 18–20). Ernst Kitzinger’s painstaking analysis of Dumbarton Oaks’ fragment of a hanging with horses and lions (fig. 21)—in which he parses its various motifs and attributes many, including the riders, to Sassanian inspiration—reveals the difficulty of this method.E. Kitzinger, “The Horse and Lion Tapestry at Dumbarton Oaks: A Study in Coptic and Sassanian Textile Design,” DOP 3 (1946): 1–72. Dumbarton Oaks, BZ.1939.13, https://www.doaks.org/resources/textiles/catalogue/BZ.1939.13. For example, he states that while the lions found on the borders of the textile resemble those on a silk from Antinoopolis, the distinctive spots on their ankles “establish their Sassanian origin beyond doubt.”Ibid., 40. He then goes on to show that some silks from Antinoopolis, which were indisputably made in Egypt, also have animals with the distinctive spot on their ankle, but argues that these textiles were intermediaries that brought Sassanian motifs to Egypt, where they enjoyed widespread popularity. Not only is the search for the origin of the horse-and-rider motif tenuous, but approaching the imagery by considering its source presumes that the later late antique viewers understood a particular rider as, say, Roman or Persian, though we do not know what they knew, if anything, about the designs’ origins.Fluck, “Dress Styles,” 160. Furthermore, these categories do not account for equestrian motifs that do not appear to derive from these sources, such as the riders on the Dumbarton Oaks textile.

The Dumbarton Oaks hanging features horses trotting over stacked fruit or other foodstuffs, or perhaps plants, a design that to my knowledge appears only on a hanging at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 22), a fragment at the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo (figs. 23–24), and the matching curtain to Dumbarton Oaks’ at the Israel Museum (fig. 11). The tapestry fragment from Cairo depicts, from top to bottom, a haloed standing figure, a large peacock-like bird, and a horse and rider trotting over a triangular dish with a mound on top, possibly representing food. This trio is bordered on one side by a chain of lozenges and on top and bottom by an Arabic inscription, which may read “Allāh” forward and backward. Though the inscription may be talismanic and illegible, the use of Arabic allows for a date of around the eighth century.According to the catalogue entry by D. Bénazeth in L’art copte en Égypte: 2000 ans de christianisme (Paris, 2000), 173, no. 178. While the design is more abstract than that of the Dumbarton Oaks hanging, it is possible to see that the rider carries in his hands similar implements—including a whip, riding crop, or scarf—and wears the same short riding jacket with pearls. The Cairo rider, however, wears a turban instead of the cap typically associated with the Persians, which is worn by the Dumbarton Oaks riders.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s hanging also has riders on horseback trotting over small items, possibly fruits, stacked in a pyramid, in addition to other similar motifs.J. Ball, in Evans and Ratliff, Byzantium and Islam, 13–14, no. 3. The horses have the exact same ornamentation as those in the Dumbarton Oaks piece and the riders wear identical outfits. Additionally, this hanging, which is complete and much larger than Dumbarton Oaks’ fragment, includes Amazons, also on horseback, as well as busts of the earth goddess Ge. The choice of flora and fauna and the arrangement of the fish, birds, lions, and T-shapes in the border are, notably, also the same.

Putti Running with Food

Small putti enclosed in medallions carrying bowls of food dash across the Dumbarton Oaks textile and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s hanging. The latter textile also features four putti with bowls of food flying against the red background immediately above, below, and to either side of the central medallion. Bowls piled high with flowers or food, perhaps dates, regularly appear on textiles attributed to late antique Egypt; a wool panel from the Rose Choron Collection, now at the Godwin-Ternbach Museum at Queens College, features four riders framed by fruit- or flower-filled bowls spaced around a square frame (fig. 25).Part of the Rose Choron Collection, recently acquired by the Godwin-Ternbach Museum at Queens College, City University of New York; W. T. Woodfin, ed., From the Desert to the City: The Journey of Late Ancient Textiles (Flushing, NY, 2018), 39, no. 1; Maguire, Weavings from Roman, Byzantine and Islamic Egypt, no. A37. In some textiles, nude and possibly allegorical figures bring offerings to gods, as in a marriage scene featuring Dionysos and Ariadne, also at the Godwin-Ternbach Museum (fig. 26).Part of the Rose Choron Collection, recently acquired by the Godwin-Ternbach Museum at Queens College, City University of New York; Woodfin, From the Desert to the City, 45, no. 14; Maguire, Weavings from Roman, Byzantine and Islamic Egypt, no. C4. The putti in the Dumbarton Oaks textile, interspersed with fish, birds, and plants, bring the bounty to the elite guests we imagine standing before the textile in its original location.

Flora and Fauna

The fish, birds, and plants may have once been easily recognized by the textile’s viewers, but their abstracted forms preclude any sure identification now. The rather distinctive spotted plant may be a mushroom or the fruit of a lotus, both of which held symbolic meaning in Egypt (fig. 27a–b).Mushrooms were linked to immortality and the spotted red mushroom (Amanita muscaria) was prized by the pharaohs. The lotus fruit was believed to promote fertility. My thanks to my anonymous reader for pointing out the possibility of lotus fruits. The fish may be perch or catfish, both common to the Nile, but a saltwater fish of the Mediterranean or Red Sea, or an imaginary fish, is not out of the question. Similarly, the birds may be aquatic fowl common to the Nile, as their wide, striped feet may indicate webbed feet; ducks were especially significant because they could be hunted year-round for food. In textiles with a Nilotic landscape, such as a fourth- to fifth-century tapestry-weave square from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the association with the Nile is usually identified by the combination of ducks, lotus flowers, and fish (fig. 28). This tapestry also has two putti, one possibly riding a hippopotamus; putti are pictured in Nilotic landscapes because they symbolized the flooding of the Nile, which was crucial for fertile land and prosperous farming.Stauffer, Textiles of Late Antiquity, no. 12.

The creatures and plants on the Dumbarton Oaks hanging are not clearly recognizable and therefore cannot be readily identified as Nilotic. Lions are not part of the Nile’s ecosystem at all and became extinct in Egypt in Pharaonic times, when they were worshiped.C. Callou, A. Samzun, and A. Zivie, “A Lion Found in the Egyptian Tomb of Maïa,” Nature 427, no. 6971 (January 15, 2004): 211–12. See also P. and M. Huet, L’animal dans l’Egypte ancienne (Saint-Claude-de-Diray, 2013), 8 and 110. As our riders have no weapons, the lions are not being hunted (figs. 2, 5). Their position in the corners of the rectangle, facing outward, jaws open and ready to pounce, instead makes them protective of the medallion and its riders. The lions can even be interpreted as apotropaic, shielding the house’s inhabitants from unseen evils.

The designer of this textile was likely not trying to recall a known type of rider (an emperor or a hunter, for example), but rather seems to be creating a new version of a mounted horseman. He trots over the lands that provide for him, the putti holding bowls perhaps filled with the flora and fauna present in the frame, and the lions protecting them—all displayed the good fortune found in the home where this textile hung. Perhaps the textile was even believed to conjure the abundance it represented, and was therefore aspirational or even magical.

The comparable pieces at the Israel Museum, the Museum of Islamic Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art bear strikingly similar motifs—so similar, in fact, that one is tempted at least to imagine a common model. The same workshop, however, was probably responsible only for the pieces at Dumbarton Oaks and the Israel Museum; the others exhibit different techniques.Analysis of dyes and weave structure may aid in the determination that the piece in Israel was made in the same workshop as the Dumbarton Oaks piece, but for now this is uncertain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s textile is done in a tapestry weave on a plain-weave wool ground. Dumbarton Oaks’ textile is also a wool tapestry but uses a linen ground. Because the Cairo fragment is much smaller it offers less technical information for comparison. While the Cairo rider trotting over a bowl of food makes for a sound comparison, the other motifs on the Cairo textile do not indicate further connections. Individually, the birds, putti, mounted horsemen, fish, and plants found on the Dumbarton Oaks, Israel Museum, and Metropolitan Museum hangings are not unusual, but only these few examples combine these scenes of abundance with a horse and rider, making a less typical overall design.

The iconographic connection to an inscribed textile placed firmly after the introduction of Arabic to Egypt (the Cairo example), suggests that the Dumbarton Oaks textile should also be placed in the period after the Arab conquest. That the Metropolitan Museum of Art hanging and the nearly identical hangings from Dumbarton Oaks and the Israel Museum have groupings of iconographic elements in common prompts a reconsideration of the date that had once been assigned to the Dumbarton Oaks textile. When it was purchased by Dumbarton Oaks, the fragment was deemed “Coptic” and dated to the fifth to sixth century—prior to the Arab conquest of Egypt—an attribution that has more or less persisted until now.Dumbarton Oaks, Handbook of the Collection (Washington, DC, 1946), 128, no. 254. In the 1970s, Deborah Thompson, who studied the collection, redated the piece to the ninth–tenth centuries, calling it “Islamic.” This date was based primarily on her view that the dark blue of the textile was related to a group of inscribed Fayyūm textiles from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (31.19.13–17); the original color of any textile, however, cannot be known without dye analysis, and there is little else relating these textiles to each other. D. Thompson, “Catalogue of Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection” (unpublished catalogue, Washington, DC, 1976), no. 157. Gudrun Bühl and Elizabeth Dospěl Williams were aware of the later date of the Israel Museum piece and Deborah Thompson’s unpublished date and mentioned to me, when I first viewed the textile on June 12–13, 2012, that Dumbarton Oaks’ date may be incorrect. The Metropolitan Museum of Art hanging is radiocarbon-dated to 640–660.See Evans and Ratliff, Byzantium and Islam, 13–14, no. 3, esp. n1. The Israel Museum dates their matching curtain to the ninth or tenth century, which seems too late given the similarities to the more firmly dated Metropolitan Museum of Art piece.The museum’s date is probably based on Baginski’s research in Baginski and Tidhar, Textiles from Egypt, no. 191. Based on a comparison of pieces with similar motifs that have more diagnostic dating criteria, I propose that the Dumbarton Oaks piece be dated to the seventh to eighth century.

Egypt in the Seventh and Eighth Centuries

Having dated this textile to the period after the Arab conquest of Egypt, I now turn to an examination of it that takes into account, as much as possible, the cultural changes resulting from Arabization and Islamization, acknowledging that, particularly in Egypt, the Roman world was not immediately wiped away.On the terms “Arabization” and “Islamization,” see M. S. A. Mikhail, From Byzantine to Islamic Egypt: Religion, Identity and Politics after the Arab Conquest (London, 2014), especially chapters five and six. Scholars have often ignored later late antiquity when examining works in textiles and other media, perhaps in part because several cultures intersected in seventh- and eighth-century Egypt, and researchers have traditionally focused only on the subject within their discipline (Roman, Byzantine, or Islamic). Archaeologists specializing in the ancient world have thus tended to analyze the textiles they have unearthed from a Roman perspective, an approach thereafter adopted by the art historians and other scholars who studied their findings. By pivoting to later late antiquity and the changes then occurring in the use of textiles in domestic interiors, greater clarity can be brought to the Dumbarton Oaks hanging.

Politically, the seventh century was tumultuous. Under Byzantine rule, the local population was increasingly upset by sanctions levied against the Coptic Church by their Greek Orthodox rulers over doctrinal differences.The literature on the Arab conquest of Egypt is extensive, but some of the most important sources are: A. J. Butler, The Arab Conquest of Egypt and the Last Thirty Years of the Roman Dominion (Oxford, 1902), esp. 33–41, 69–92, 194–464; F. M. Donner, The Early Islamic Conquests (Princeton, NJ, 1981); H. Kennedy, The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In (Philadelphia, 2007), 139–68; Mikhail, From Byzantine to Islamic Egypt, esp. 51–135. In the last decades of Byzantine rule, Herakleios (610–641) pushed for the unification of Christian sects, which was met with substantial opposition.Kennedy, Great Arab Conquests, 144–45. The Persians invaded in 618, though little is known about the effects on the local culture, as the Byzantines regained power under Herakleios in 629. With Egypt destabilized by a fledgling Byzantine administration and fighting between the Coptic and Byzantine Churches, the Muslim armies invaded in 639, forcing the Byzantines out by 641.

Arabization, a linguistic shift, and Islamization, which involved not only conversion to Islam but also the recasting of cultural paradigms to fit within an Islamic worldview, were still occurring in Egypt in the ninth and tenth centuries. This complex set of processes included the immigration of Arabs, a linguistic change from Greek and Coptic to Arabic, conversion to Islam, changes in government, as well as more nuanced cultural shifts that are harder to pin down. It is difficult to precisely chart the Arabization of the culture, as both continuity and change are recognizable in the sources. In the government, while top officials were replaced with Arab leaders, low-level administrators were kept in place.P. Sijpesteijn, “The Arab Conquest of Egypt and the Beginning of Muslim Rule,” in Bagnall, Egypt in the Byzantine World, 444. And while the last datable Greek papyrus was written in 797, the first Arabic papyri date shortly after the conquest of Egypt, in 643.Ibid., 446. Arab immigration was swift, especially in Fusṭāṭ, which Petra Sijpesteijn describes as becoming “quickly overcrowded” in the seventh century, with evidence of Arabs beginning to populate the countryside as a result.Ibid., 452.

One may not wish to make too much of this difference, as late antique Egypt and Egypt after the Arab conquest were multilingual, multireligious, and multiethnic places with the same Hellenistic past. This might explain why the textiles feature figures like the putti, as well as their affinity for Persian-inspired design, such as the horse and rider so common in Sassanian Persia.The popularity of the “Persian rider” motif and its Sassanian origins are well established and discussed at length in Kitzinger, “Horse and Lion Tapestry.” See also E. C. Dodd, “On the Origins of Medieval Dinanderie: The Equestrian Statue in Islam,” ArtB 51, no. 3 (1969): 227. But despite a continuity of Greek and Coptic language and religion—and, we can infer, customs in general—the spread of Arabic and growth of the Arab population were rapid enough to affect factors like consumers’ preferences for certain motifs and the demand for certain textiles as the manner in which people circulated in their interiors and used their furnishings may have changed.By the ninth century, the use of Arabic overtakes Greek and Coptic in both the Christian and the Jewish sources, where Coptic is referred to as a foreign language; see, e.g., Sijpesteijn, “Arab Conquest,” 454.

“Then Allah brought them curtains and all good things”

One potential reason why textiles like the Dumbarton Oaks hanging are rarely studied from an Islamic perspective may be their employment of figural decoration, given the common assumption that Muslim belief dictated that figural imagery must be avoided. It was likewise the norm for textile catalogues up until the 1980s to categorize objects on the basis of design: textiles with aniconic, geometric designs were typically classified as “Islamic” rather than Coptic Christian or late antique.See, e.g., Volbach and Kühnel, Late Antique, Coptic and Islamic Textiles of Egypt, and The Art of the Ancient Weaver: Textiles from Egypt (4th–12th Century AD) (Ann Arbor, MI, 1980). One exception may be D. Thompson, Coptic Textiles in the Brooklyn Museum (Brooklyn, NY, 1971), in which the author dates a group of figurative textiles after the eighth century (see, e.g., no. 38). The 1946 catalogue of the Dumbarton Oaks collection titles the hanging “Medallion with Two Mounted Figures, Wool, Coptic, from Antinoe, Egypt, V–VIth century”—a description that focuses on the horsemen even though they may not have been the central focus of the textile in its original form.Dumbarton Oaks, Handbook of the Collection, 128, no. 254. This description is also indicative of the tendency to date figural textiles to the pre-Islamic period, although textual and scientific research has shown that this is not a sound method of dating.De Moor, Van Strydonck, and Verhecken-Lammens, “Radiocarbon Dating,” 181–87, explain radiocarbon dating for the lay reader and discuss several objects whose dates based on style were later adjusted. Muslim belief and religious aesthetics were much more complicated than is implied by the many catalogues that establish such rigid categorizations.

The aḥādīth, traditional accounts and sayings of the Prophet Muḥammad (ca. 570–632 CE) written down in the eighth and ninth centuries, were used by Muslims as a model for how to live a life pleasing to God. Despite debate regarding whether the aḥādīth were truly spoken by Muḥammad, they reflect actual practices and anxieties about practices that may not have adhered to Muḥammad’s teachings. Curtains and hangings are mentioned often in the aḥādīth, especially with regard to their role in revealing important figures, including the Prophet himself, who frequently emerges from behind a curtain ceremoniously. One example is from the Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī: “Narrated Anas: ‘The Prophet did not come out for three days. The people stood for the prayer and Abu Bakr went ahead to lead the prayer. (In the meantime) the Prophet caught hold of the curtain and lifted it. When the face of the Prophet appeared we had never seen a scene more pleasing than the face of the Prophet as it appeared then. The Prophet beckoned to Abu Bakr to lead the people in the prayer and then let the curtain fall. We did not see him (again) till he died.’”Muḥammad ibn Ismāʿīl al-Bukhārī, Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 681, bk. 10, no. 75, trans. M. Muhsin Khan, Sunnah.com, http://sunnah.com/bukhari/10/75. There are also many discussions of curtains in relation to modesty. For example: “Ibn Abbas said: ‘Allah is Most Clement and Most Merciful to the believers. He loves concealment. The people had neither curtains nor curtained canopies in their houses. Sometimes a servant, a child or a female orphan of a man entered while the man was having sexual intercourse with his wife. So Allah commanded them to ask permission in those times of undress. Then Allah brought them curtains and all good things.’”Abū Dāwūd al-Sijistānī, Sunan Abī Dāwūd 5192, bk. 43, no. 420, http://sunnah.com/abudawud/43/420.

It seems that, similar to the effects of Christianity on Roman traditions, Islam introduced an increased concern with modesty and concealment in the context of domestic life, in addition to social and economic changes.On the privatization of space in the Christian late antique household, see K. Sessa, “Christianity and the Cubiculum: Spiritual Politics and Domestic Space in Late Antique Rome,” JEChrSt 15, no. 2 (2007): 171–204. Friedrich Ragette argues that the design of houses across the Arab world shifted to accommodate Islamic laws regarding gender, privacy, and cleanliness: F. Ragette, Traditional Domestic Architecture of the Arab Region (Fellbach, 2012). The archaeological record of Roman houses from the first to the seventh century points to the creation of more intimate domestic environments by building smaller doorways into private spaces and making these rooms less proximal to main entrances.See especially F. Guidobaldi, “L’edilizia abitativa unifamiliare nella Roma tardoantica,” in Società romana e impero tardoantico, ed. A. Giardina (Rome, 1986), 2:165–237; S. P. Ellis, “The End of the Roman House,” AJA 92, no. 4 (1988): 565–76; L. Özgenel, “Public Use and Privacy in Late Antique Houses in Asia Minor: The Architecture of Spatial Control,” in Housing in Late Antiquity: From Palaces to Shops, ed. L. Lavan, L. Özgenel, and A. Sarantis (Boston, 2007), 239–81. Yvon Thébert argues that, beginning in the late Roman period, domestic interiors became more compartmentalized, with rooms developed for specialized uses, changes he attributes to a greater emphasis on personal modesty.Y. Thébert, “Private Life and Domestic Architecture in Roman Africa,” in A History of Private Life, vol. 1, From Pagan Rome to Byzantium, ed. P. Veyne (Cambridge, MA, 1987), 313–410. John W. Stephenson adds to this idea, arguing that compartmentalization in Christian homes increased due to religious reasons: J. W. Stephenson, “Veiling the Late Roman House,” Textile History 45, no. 1 (2014): 3–31. Helen Saradi documents the same trend in the early Byzantine period, but considers the reasons for the change to be economic as well as social.H. Saradi, “Privatization and Subdivision of Urban Properties in the Early Byzantine Centuries: Social and Cultural Implications,” BASP 35, no. 1/2 (1998): 17–43. She describes the use of curtains to divide families from one another when large urban homes were subdivided into apartments, a phenomenon that she says was underway by the fourth century around the Mediterranean.Ibid., 17. Thus, changes to domestic architecture had already begun long before the Dumbarton Oaks textile was made.

Lisa Golombek, in her seminal article “The Draped Universe of Islam,” describes the incredible displays of thousands of textiles in ceremonies of the Umayyad, ʿAbbāsid, Fāṭimid, and other courts of the Islamic world.L. Golombek, “The Draped Universe of Islam,” in Content and Context of Visual Arts in the Islamic World: Papers from a Colloquium in Memory of Richard Ettinghausen, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 2–4 April 1980, ed. P. P. Soucek (University Park, PA, 1988), 25–38. She argues that, beyond their role in dazzling the viewer, curtains and hangings were used for theatrical effect and concealment, for example, to reveal the enthroned caliph at a particular moment in a ceremony, or to give privacy to those praying around the miḥrāb in the mosque. The Dumbarton Oaks hanging could have served to create private space or add drama to a domestic setting.

Because the aḥādīth were used by some Muslims to interpret the Qurʾān and as the basis for developing Islamic law, it is interesting to see what they say about textiles with figural decoration. They contain a surprising number of references to textiles, though many of the stories repeat with just a few variations. One story mentions Muḥammad entering a home in which he sees a curtain ornamented with all sorts of figural decoration. In most versions he is angry, rips it down, and tears it in half; it is then noted that cushions are made out of it, presumably—though it is not explicitly stated—without the figural parts displayed.I have found over twenty versions of this story in the aḥādīth. Interestingly, in some versions he is not angry and the anecdote is told so matter-of-factly that it could be interpreted that the figural decoration had nothing to do with the transformation of the curtain into cushions. In one example in the Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, the Prophet may have torn the curtain accidentally, as the potentially offensive decoration is not highlighted: “ʿAisha said that she hung a curtain decorated with pictures (of animals) on a cupboard. The Prophet tore that curtain and she turned it into two cushions which remained in the house for the Prophet to sit on.”Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 2479, bk 46, no. 40, http://sunnah.com/bukhari/46/40.

There is enough ambiguity in the aḥādīth to suggest that curtains with figural decorations were common and not necessarily considered problematic for use by Muslims. One passage appears to exempt textiles with “pictures” (figural images in this context) from any restrictions:

Abu Talha reported that Allah’s Messenger said: “Angels do not enter a house in which there is a picture. Busr said: Zaid b. Khalid fell sick and we visited him to inquire after his health. As we were in his house (we saw) a curtain having pictures on it. I said to ʿUbaidullah Khaulani: Did he not narrate to us (the Holy Prophet’s command pertaining to pictures)? Thereupon he said: He in fact did that (but he also said): Except the prints upon the cloth. Did you not hear this? I said: No, whereupon He said: He had in fact made a mention of this.”Muslim ibn al-Hajjāj, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2106e, bk. 37, no. 133, http://sunnah.com/muslim/37/133.

Abu Talha’s story presents a liberal position on figural imagery, which parallels other sources from the Islamic world indicating that figuration was acceptable in certain contexts. The tenth-century Persian explorer Ibn Rustah describes the Prophet Muḥammad’s wool tent as having an array of beasts such as eagles, lions, and even human figures on it.Golombek, “Draped Universe,” 105. While the reliability of a centuries-later description of the Prophet’s tent may be questioned, it demonstrates that figural textiles were acceptable in a domestic context. Golombek describes several examples of tents woven with figures in the early Islamic world, attributing the trend to both Sassanian and early Christian precedents.Ibid.

The use of textiles with figural decoration caused some anxiety in Jewish society, where we find sources discussing textiles similarly to those in the aḥādīth. In the twelfth century, Moses Maimonides (1135/38–1204) received a letter inquiring how one should properly pray when at home. Generally, Jews were instructed to face a wall so as not to be distracted by objects, but the correspondent wonders what one should do when confronted with a wall decorated with textiles or stuccowork replete with figures, which was apparently commonplace. Maimonides responded that, while it is “a nuisance,” one should not remove the decoration but simply pray with eyes closed.Goitein, Mediterranean Society, 4:121. The archaeological record presents a complicated picture of the Jewish relationship to figural art. There are surviving synagogues predating our textile that are decorated with animals and humans.Dura Europos in Syria (ca. 240), Beit Alfa and Na’aran in Israel (fifth century), and Hammam Lif in Tunisia (sixth century) are just a few examples of synagogues with figural decoration. Hammam Lif’s sixth-century floor mosaics, discovered in 1883 near Tunis, depict many types of birds, fish, lions, and other quadrupeds.K. Stern, “Mosaics from the Hammam Lif Synagogue,” in Evans and Ratliff, Byzantium and Islam, 110–12, nos. 73a–c. Joseph Shatzmiller, discussing German Jews of the High and late Middle Ages, contends that the Jews who decorated sites such as Hammam Lif did not see these figurative images as breaking the Second Commandment; he notes, though, that Jews stopped making floor mosaics in the seventh century, which he attributes to their contact with Islam.J. Shatzmiller, Cultural Exchange: Jews, Christians, and Art in the Medieval Marketplace (Princeton, NJ, 2013), 75. As with the record on Muslims’ use of figural imagery in textiles, evidence of Jewish use is ambiguous. Indeed, the documents of the Cairo Geniza, the bulk of which were written in Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew and date to the ninth through thirteenth centuries, contain many mentions of textiles with animals and some mythological creatures.The griffin, a creature from Persian mythology, is mentioned along with several animals such as birds and lions: Goitein, Mediterranean Society, 4:113. While some Geniza documents date to as many as four centuries after the earliest-written aḥādīth, I mean to show here that, across religions, figural curtains like that at Dumbarton Oaks remained common despite changes in attitudes about figural art.

Textiles in the Home

The archaeological record concurs with the literary sources discussed above, as do other historical records. Trousseau lists, in particular, make it clear that curtains and hangings were the most important furnishing textiles in the home and that figural images did not die out. Moreover, a single textile may have served as a wall hanging, a curtain used to divide space, a bedspread, or a seating cover draped over hard furniture. Inventories of the possessions brides brought with them to a marriage, whether they were Muslim, Jewish, or Christian, survive in fairly large numbers between the eighth and fourteenth centuries and demonstrate that textiles were the most common of these items. Among those textiles, curtains and bedding are mentioned in the sources most frequently.See the Cairo Geniza documents as discussed in Goitein, Mediterranean Society. On marriage contracts, see Y. Rapoport, Marriage, Money and Divorce in Medieval Islamic Society (Cambridge, 2005). N. Oikonomides, “The Contents of the Byzantine House from the Eleventh to the Fifteenth Century,” DOP 44 (1990): 208–10, identifies “sleeping equipment,” which included curtains, as the most common item listed in wills.

Wooden screens were often used in windows, and doors were typically made of wood as well. Although in many cases curtains were hung in windows and doorways instead, this was not their most common function.Laila ‘Ali Ibrahim surveys residential architecture from early Islam through Mamlūk times in Cairo and describes window screens as being standard and curtains as copious: L. ‘A. Ibrahim, “Residential Architecture in Mamluk Cairo,” Muqarnas 2 (1984): 47–59, esp. 47–50. Rather, curtains were most typically used as spatial dividers in antiquity and the Middle Ages. Even within a modestly sized house, sleeping spaces were cordoned off with curtains. The Cairo Geniza reports on a bride who was so poor she only had four pillows and one set of curtains “for the arch,” suggesting that, at a bare minimum, a room divider was needed for privacy.Goitein, Mediterranean Society, 4:122. In a grander house, curtains were used to divide other parts of the interior, perhaps separating the sexes for activities such as dining or when guests were present.

Yossef Rapoport reports in his book on Islamic marriage laws and customs that an emir’s daughter in Mamlūk Egypt marrying the sultan’s son brought with her a dowry that was so huge it had to be carted by eight hundred porters and one hundred mules. The items listed include some hard furnishings and utensils, but the bulk of the bride’s goods were textiles. This is a late, and extreme, example, but Rapoport’s research shows that, at every economic level dating back at least to the eighth century, early Islamic society—like Christian and Jewish society—was dotal, despite marriage laws that only required men to pay a bride price.Rapoport, Marriage, Money and Divorce. Thus, dowries in Islam, which routinely included textiles, were customary though never part of a marriage contract. Interestingly—and unusually, in comparison with other religions—Muslim women legally retained their trousseaux so that when a couple divorced, which was surprisingly common, the household goods remained with her; land and property remained with the men.Ibid. This shows the value of textiles as adaptable goods; they were not made for a specific home and could move in the event of divorce. Textiles were likely repurposed as needed depending on location, season, or even occasion.

Textiles as Talismans

As common and necessary items in a dowry, textiles were inextricably linked to marriage. Thus, it is not surprising that from ancient times they were also used as talismans for a good, long-lasting marriage and fruitful home.This idea is discussed in relation to textiles in K. Weitzmann, ed., Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century; Catalogue of the Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 19, 1977, through February 12, 1978 (New York, 1979); Art of the Ancient Weaver; Maguire, Maguire, and Duncan-Flowers, Art and Holy Powers; and I. Kalavrezou, ed., Byzantine Women and Their World (Cambridge, MA, 2003), to name a few. In late antiquity, two demons, Modabeel and Katanikotaeel, were believed to disrupt harmony in marriages and cause divorce; some surviving objects are thought to have offered protection from divorce.A. Walker, “Home: A Space ‘Rich in Blessing,’” in Kalavrezou, Byzantine Women and Their World, 219. Further, as the authors of Art and Holy Powers have shown, in the late Roman and Byzantine world images alone could be magical.Maguire, Maguire, and Duncan-Flowers, Art and Holy Powers.

Scenes of prosperity and bounty, like those found on the Dumbarton Oaks fragment, were considered in Roman times to be talismanic for a good marriage and a flourishing home.Ibid., 8. The earth produced the flora and fauna seen on the textile, which one hoped would supply food for the table. Ducks, as previously noted, were of particular importance: they could be hunted in all seasons, so they kept one from starving in winter. In the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, mushrooms were linked to immortality and associated with the gods; however I have not been able to determine whether these beliefs lasted into Roman and later times.Fungi of Egypt, Arab Society for Fungal Conservation, http://www.fungiofegypt.com/history.html, citing The Egyptian Book of the Dead (The Papyrus of Ani), trans. E. A. W. Budge [1895] (Mineola, NY, 1967). Lotus fruit, which may be depicted on the textile, was thought to promote fertility. The horse and rider could also symbolize abundance and prosperity: horses were expensive to own and were used to hunt, thereby providing food for the household.Maguire, Maguire, and Duncan-Flowers, Art and Holy Powers, 11. As mentioned above, the hanging’s details may not have been immediately legible, but rather viewers might have taken in each part of the image slowly while dining in or visiting the great space where it was hung. All of these meanings were possible, even at once, and viewers may have recognized some but not others. Whether or not a particular viewer understood horses as essential for hunting, for example, or believed that mushrooms prolonged life, the overall message of prosperity would have been clear.

However the evidence for belief in magic just discussed is largely Roman. We must therefore examine whether a belief in the talismanic powers of objects persisted into the Islamic period, and likewise whether this type of imagery on a household textile continued to conjure associations with abundance. Emilie Savage-Smith cautions that most of what can be said about early Islamic practices with regard to magic is speculative, as the bulk of the source material either predates Islam or is from the twelfth century and later.E. Savage-Smith, ed., Magic and Divination in Early Islam (Aldershot, UK, 2004), xiv. The aḥādīth contain many references to “hanging amulets” and “charms,” though they do not specify what materials these were made from; perhaps they could have been made from a variety of things, including textiles.I have found six references to “hanging amulets,” in most cases considered a shirk (a rival to Allāh): https://sunnah.com/search/?q=amulet. Similarly, there are eight mentions of charms that clearly suggest that they are physical objects (as opposed to spells): https://sunnah.com/search/?q=charm. Talismans survive from the early period and nearly always have repeating inscriptions on the object invoking Allāh or quoting the Qurʾān, which was the primary charm used in Islamic magic.Savage-Smith, Magic and Divination, xvii. There is a clear record of the use of talismans in the homes of newly married couples both in the pre-Islamic Arab world as well as in later twelfth-century sources, suggesting a continuity in the belief that a new home had to be magically prepared for the couple.Ibid., 126, and J. Henninger, “Beliefs in Spirits among the Pre-Islamic Arabs,” in Savage-Smith, Magic and Divination, 22. When someone was sick, placing a talisman near the bed was common; a curtain with a repeating inscription may have served as an appropriate talisman.T. Canaan, “The Decipherment of Arabic Talismans,” in Savage-Smith, Magic and Divination, 126.

Indeed, the textile from the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo with the horseman riding over a pile of fruit has a partial inscription that I propose is talismanic. While the only catalogue to publish this textile noted that the inscription was in Arabic, it was not translated, perhaps because of the difficulty in reading it.D. Bénazeth, catalogue entry in Art copte, 173, no. 178. It appears to read “Allāh”—the most commonly found talismanic inscription—forward and then backward, but with a crucial error: the initial alif is connected to the second letter, lam, which is not found in inscriptions of the word “Allāh,” rendering it nonsensical.Canaan, “Decipherment,” 135. Matthew Saba, 2014–16 Mellon Curatorial Fellow, Islamic Art Department, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Abdullah Ghouchani, consultant, Islamic Art Department, Metropolitan Museum of Art, examined photographs of the inscription with me in January 2015, and helped me to decipher it. However, legibility is not required of a talisman, and illegibility is, in fact, typical. Tewfik Canaan has found that, of the four major types of talismanic inscriptions, two are purposefully unintelligible, forming single words without meaning or signs and letters strung together illegibly.Canaan, “Decipherment,” 127.

Four tapestry squares dated to the eighth to ninth century in Egypt have similar inscriptions and serve as a good comparison for the Cairo textile. “Allāh” is written within their red frames with the first and second letters connected as in the inscription on the Cairo piece (fig. 29).F. Calament, catalogue entry in Ein Gott: Abrahams Erben am Nil; Juden, Christen und Muslime in Ägypten von der Antike bis zum Mittelalter, ed. C. Fluck, G. Helmecke, and E. R. O’Connell (Berlin, 2015), 201, no. 215. Thanks to Matthew Saba for pointing out to me that the inscription on this textile had the same letter construction as the Cairo piece. The illegibility and repetition of “Allāh” point to a talismanic function. In the aḥādīth, for example, the repetition of “Allāh” serves as a cure for harmful magic.Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 6391, bk. 80, no. 86, http://sunnah.com/bukhari/80/86: “ʿAisha said, ‘Allah’s Messenger was bewitched, so he invoked Allah repeatedly requesting Him to cure him from that magic.’” The four letters of “Allāh” were used in talismans with no diacritics and arranged, sometimes in illegible patterns, to invoke God magically, recalling other important arrangements of four—the four seasons, the four cardinal points, the four elements, the four archangels, and so on.Canaan, “Decipherment,” 135. I wish to consider that the inscription on the Cairo piece could have been talismanic, though fragmentary evidence resists its reconstruction as a curtain or other furnishing textile.

Most important for our discussion, it was likely the inscription, rather than the images, that gave this particular textile its magic power. In his discussion on the continuity in the use of talismans from the pre-Islamic to the Islamic period, including those with animal imagery, Finbarr Barry Flood has noted that words—whether a Qurʾānic inscription, unintelligible words, or one of the ninety-nine names of God—increasingly came to yield power.F. B. Flood, “Image against Nature: Spolia as Apotropaia in Byzantium and the Dār al-Islām,” Medieval History Journal 9, no. 1 (2006): 143–66. The images of prosperity on the Dumbarton Oaks textile probably evoked abundance, but it is difficult to determine whether the user hoped that these images would actually bring about good fortune.

Finally, the placement of lions in the corners of the square framing the inner medallion of the Dumbarton Oaks textile, as if to ward off an unseen evil, suggests an apotropaic purpose. Lions, along with rams and dogs, were painted at the entrance to one aristocratic house in Umayyad Iraq for protection against wild beasts.Ibid., 153. The Cairo Geniza contains a text that recommends creating images of lions and other wild animals to expel them from the city.Ibid. As textiles were used in liminal spaces to protect, bar entry, or conceal, perhaps the animals on them could serve a talismanic purpose. Certainly, the entire environment of the Dumbarton Oaks textile, with its mixture of Nilotic, pastoral, and mythological imagery, was not intended as a true representation of this world. Rather, the textile pictures a world of plenty, perhaps for a magical purpose, whether protective or invoking abundance for the household. In early Islam, these symbols of plentiful food proliferated, and it seems logical that ducks, lions, fish, and mushrooms or lotus fruits would have continued to signify wealth and bounty as they had in earlier times.

Conclusion

The use of household textiles in Egypt after the Arab conquest, which is when I propose the Dumbarton Oaks textile was made, was similar to that in Byzantine Egypt, but the meanings of the iconography may have shifted away from the belief that imagery of Nilotic abundance and Roman symbols of wealth, such as a mounted hunter, could magically bring about prosperity, and toward more general aspirational motifs of terrestrial abundance. Curtains and hangings were used primarily in architectural settings to divide space and provide privacy, which in seventh- to eighth-century Egypt, no matter the religion of the household, seems to have become increasingly important, according to the aḥādīth as well as documentary evidence of inventories of household goods.