Determining the original functions of extant textiles from late antique Egypt can be challenging. Since most textiles survive in fragmentary condition, conclusions about their original uses are generally based on observations of dimension, composition, and iconography. Art historical information about these textiles can be supplemented by examination of the techniques and materials employed in their creation.See K. Colburn, “Materials and Techniques of Late Antique and Early Islamic Textiles Found in Egypt,” in Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, ed. H. C. Evans and B. Ratliff (New York, 2012), 161–63.

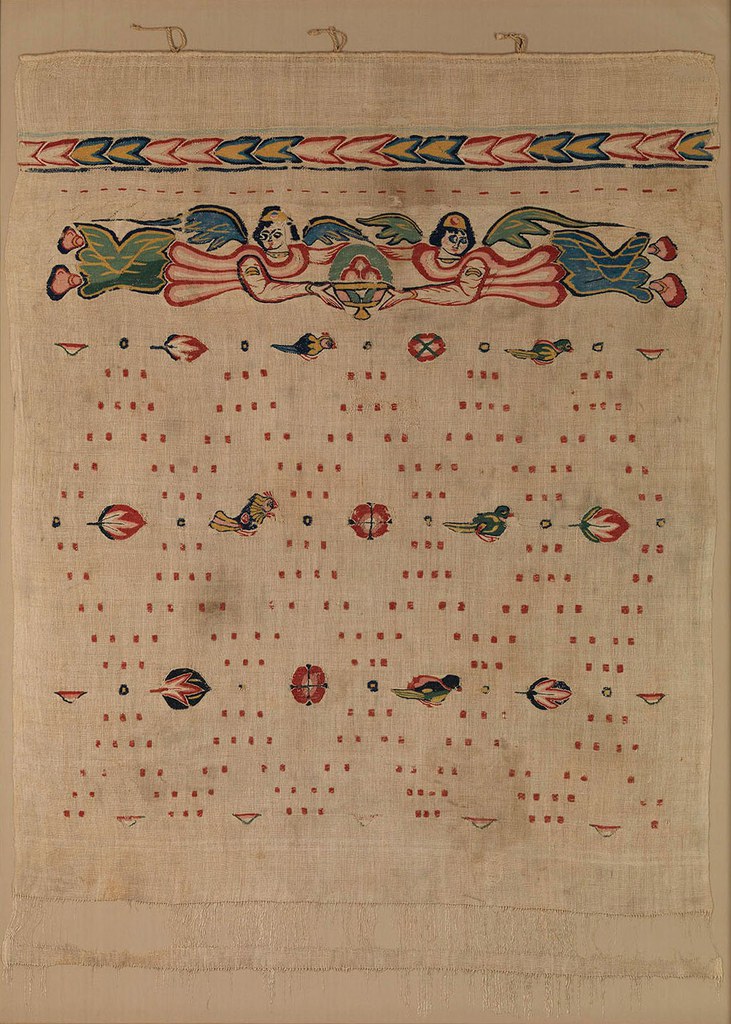

This essay presents a case study of a unique late antique Egyptian hanging with a design woven in weft-loop pile in wool, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (90.5.808, fig. 1).For additional images, see http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/444287. Although it survives in fragmentary condition, the textile retains sufficient technical information about its weaving process to allow for some informed speculation about its original function. Recently conducted technical analyses—including dye analysis and radiocarbon dating—indicate that the Met’s hanging should be considered in relation to a growing body of data gathered from the examination of related textiles in other collections. The results of the analyses of the Met’s textile offer a valuable comparative point for this body of material as a whole. Most notably, it preserves remnants of cords, rare surviving evidence of its method of installation in an architectural setting.

Weft-Loop Pile Weavings

The Metropolitan Museum of Art houses a rich collection of textiles in weft-loop pile from late antique Egypt. This technique produces a fabric with distinctive characteristics and a relatively firm weave structure with designs created from the face-protruding loops. These features make it suitable for furnishings, such as hangings suspended vertically within spaces and against walls (fig. 2a–c), and as covers and blankets for horizontal surfaces (figs. 3 and 4a–b).

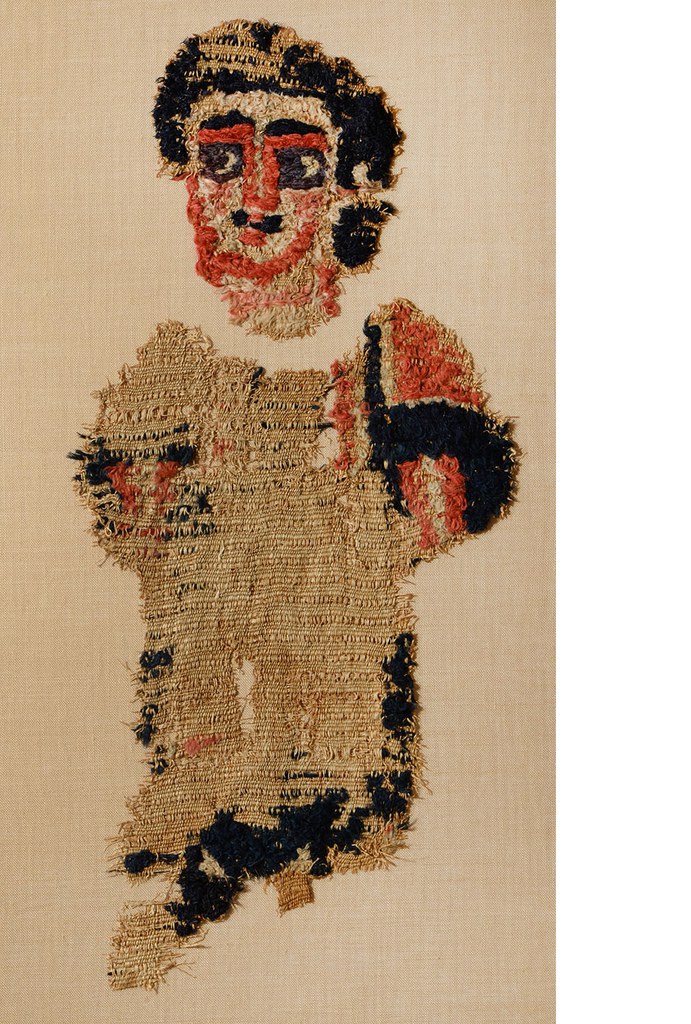

In addition to being decorative, pile weavings also added to domestic comfort. The thickness of the pile served as a form of insulation when hung on walls and enhanced the comfort of hard furnishings by providing cushioning. These qualities made this technique appropriate for clothing as well: pile has been identified within and, more rarely, on the outside of some tunics, where the loops shielded the wearer against harsh weather (figs. 5a–b and 6a–b).For additional images, see http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/444374. For a discussion on this tunic, see K. Colburn, “A Closer Look at Textiles from the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Materials and Techniques,” in Designing Identity: The Power of Textiles in Late Antiquity, ed. T. K. Thomas (Princeton, NJ, 2016), 132. For a sleeve fragment of a tunic with loop pile on the reverse (the original interior of the tunic), see Metropolitan Museum of Art, 90.5.829, http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/444308. An example of a complete tunic woven in weft-loop pile facing the garment’s exterior is also in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 26.9.6, http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/447842. See O. Wulff and W. F. Volbach, Spätantike und koptische Stoffe aus ägyptischen Grabfunden in den Staatlichen Museen, Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, Ägyptisches Museum, Schliemann-Sammlung (Berlin, 1926), 47 and plate 73, for an example from the Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst in Berlin (inv. 2881) that was lost in World War II (Kriegsverlust). See also R. Cortopassi and C. Verhecken-Lammens, “Tunics with Loops: 14C, Spinning, Weaving, Dyes and Iconography,” in Methods of Dating Ancient Textiles of the 1st Millennium AD from Egypt and Neighbouring Countries, ed. A. De Moor and C. Fluck (Tielt, 2007), 139–49. For a discussion on weft-loop pile textiles, which includes a rare example of a tunic fragment with pile on both sides, see S. Tsourinaki, “Looped-Pile Textiles in the Benaki Museum (Athens),” in Ancient Textiles: Production, Craft and Society, ed. C. Gillis and M.-L. B. Nosch (Oxford, 2007), 143–49.

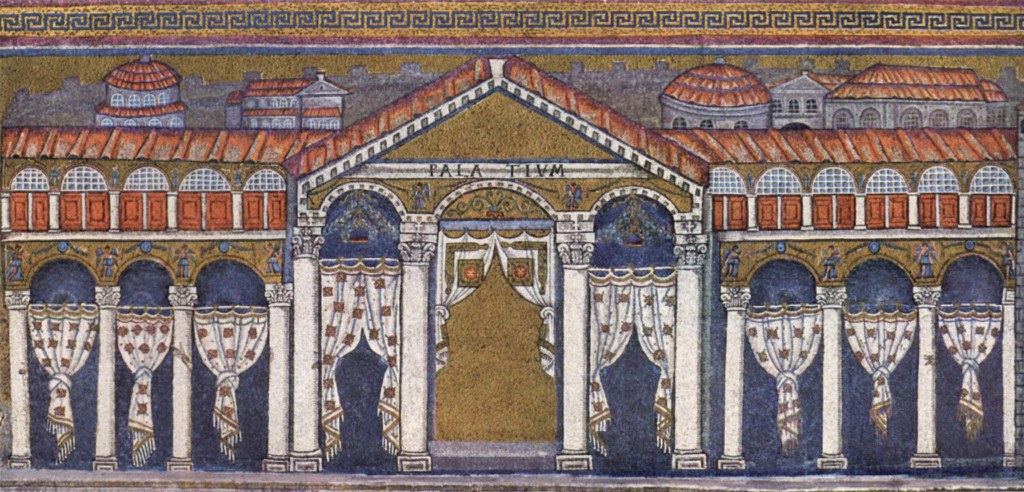

The versatility of these weavings was limited, however. It is debatable, for example, whether textiles in this technique were knotted or wrapped around architectural elements in palaces, private homes, and public spaces, as is depicted in mosaic representations at the basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna (fig. 7).E. Swift, Style and Function in Roman Decoration: Living with Objects and Interiors (Farnham, UK, 2009), 26–28. The substantial amount of material used to create the pile could make these weavings rigid and heavy, disrupting the drape of the fabric. Lighter-weight fabrics, and those with repeating designs, would have been more effectively used, and may indeed be what we see illustrated in some late antique wall mosaics (fig. 8).For additional images, see http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/444323

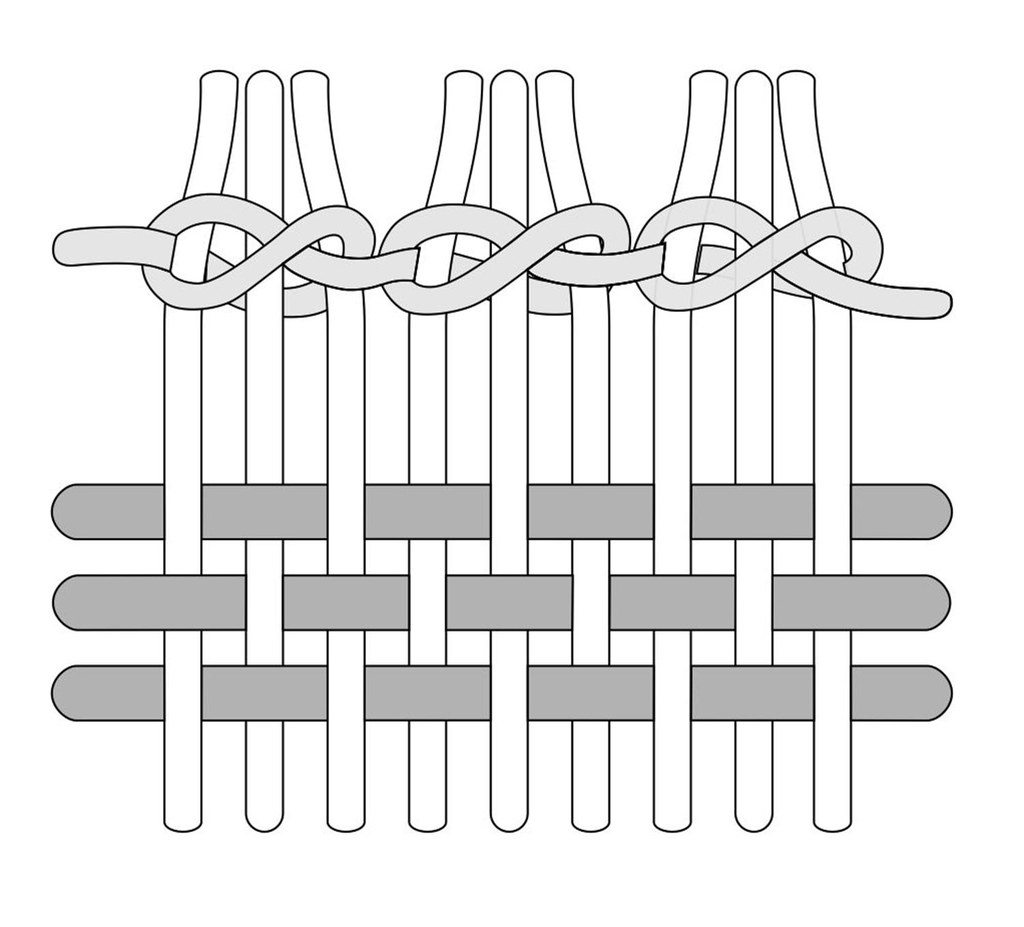

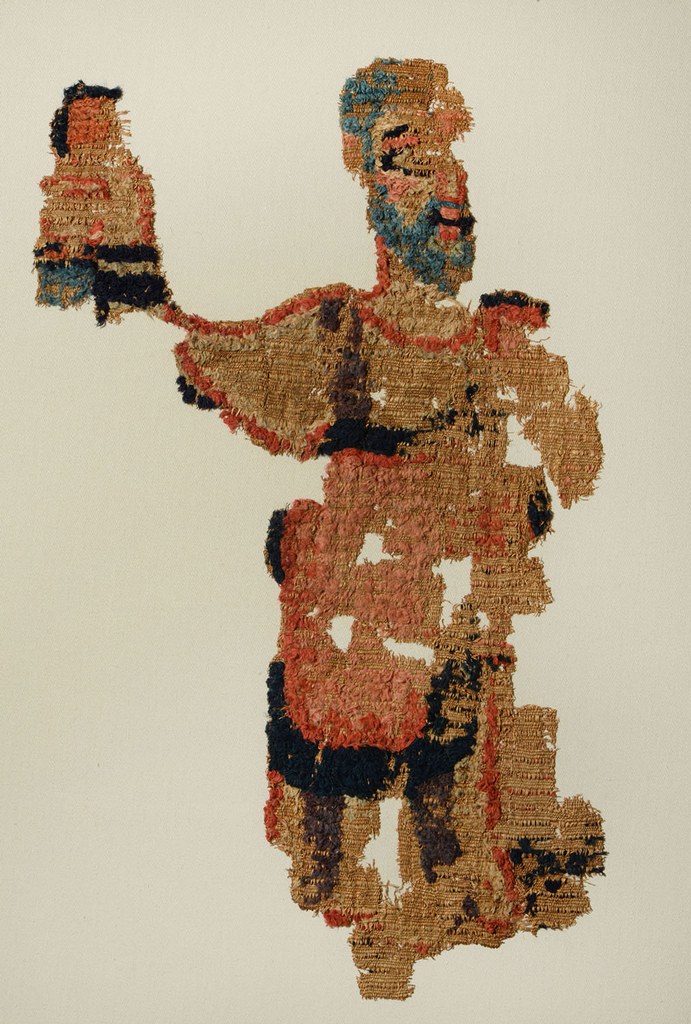

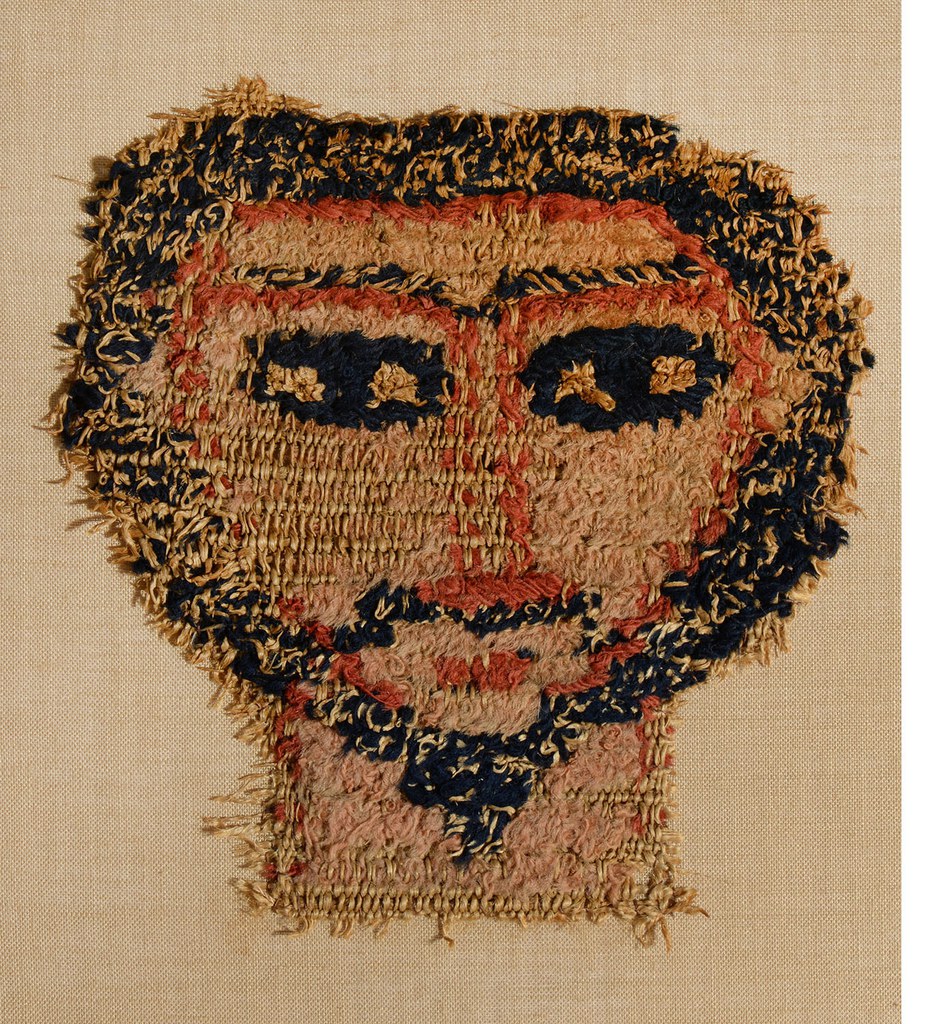

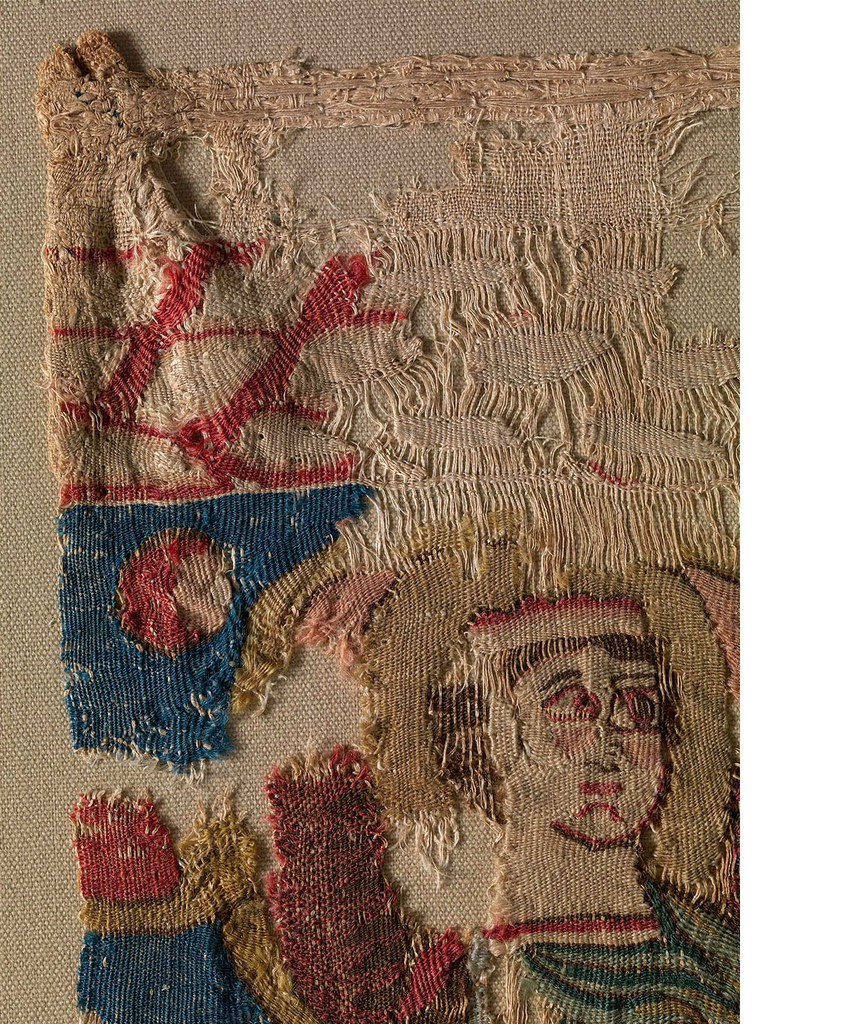

Technical analysis of weft-loop pile textiles reveals several types of loops, all created with supplementary wefts in undyed linen, dyed wool, or a combination of both.C. Verhecken-Lammens “Linen Furnishing Textiles with Pile in the Collection of Katoen Natie,” in Clothing the House: Furnishing Textiles of the 1st Millennium AD from Egypt and Neighbouring Countries; Proceedings of the 5th Conference of the Research Group “Textiles from the Nile Valley,” Antwerp, 6–7 October 2007, ed. A. De Moor and C. Fluck (Tielt, 2009), 132–43. The length of the loops can vary even within the same textile, creating areas of higher and lower pile, and thus enhancing the three-dimensionality of the weavings. The quality of the fabric differs depending on the warp and weft thread count per centimeter and the placement of the loops, which can appear closer or further apart, and sometimes cover almost the entire surface. Typically, a weaving with a lower warp and weft thread count results in a more open weave and a looser appearance. A higher count produces a denser fabric, allowing the composition to be woven with more detail.For a definition of thread count, see D. K. Burnham, Warp and Weft: A Textile Terminology (Toronto, 1980), 151. This can be seen, for example, in a weft-loop pile weaving from the Met (fig. 9).For additional images, see http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/44. Here, the closely placed wool loops in a variety of pink hues suggest the modeling of the facial features.

It is uncertain whether weavers who specialized in the loop pile technique (kaunakopoioi) used pattern sheets to aid in the weaving of the composition, as is known for tapestry weaves.S. Schrenk, “Spätrömisch-frühislamische Textilien aus Ägypten,” in Ägypten in spätantik-christlicher Zeit: Einführung in die koptische Kultur, ed. K. Kraus (Wiesbaden, 1998), 355, and A. Stauffer, Antike Musterblätter: Wirkkartons aus dem spätantiken und frühbyzantinischen Ägypten (Wiesbaden, 2008). Annette Paetz gen. Schieck observed regarding a textile in the Katoen Natie collection that the contours of the figures were painted on the warp threads, to aid the weaver in the weaving process. See “Apa Philoxenos’ curtain,” KTN 1735, in Favourite Fabrics from the Katoen Natie Textile Collection: A Liber Amicorum for Antoine De Moor, ed. C. Fluck and P. Linscheid (Tielt, 2017), 150. See also Riggisberg, Abegg-Stiftung, inv. 8 a, b: S. Schrenk, Textilien des Mittelmeerraumes aus spätantiker bis frühislamischer Zeit (Riggisberg, 2004), 51–53. Occasionally, tapestry-woven designs, such as monochrome horizontal borders, were incorporated within the pile weave, and top and bottom edges sometimes ended in warp fringes (fig. 3). Not surprisingly, scholars have compared the results of this technique to mosaics (fig. 10).Schrenk, “Spätrömisch-frühislamische Textilien,” 356. Both mosaics and weft-loop fabrics have a striking appearance when viewed from a distance. And both techniques demonstrate subtle gradations in the arrangement of blocks of color side by side: like the arrangements of tesserae in mosaics, the strong color scheme of the clustering loops in these weavings made it possible to create a vibrant play of light and shadow. Indeed it is likely that weft-loop pile developed to replicate the visual effects of mosaics, as textiles have the distinct advantage of being easily movable according to owners’ changing needs or aesthetic preferences.

The Peacock Hanging

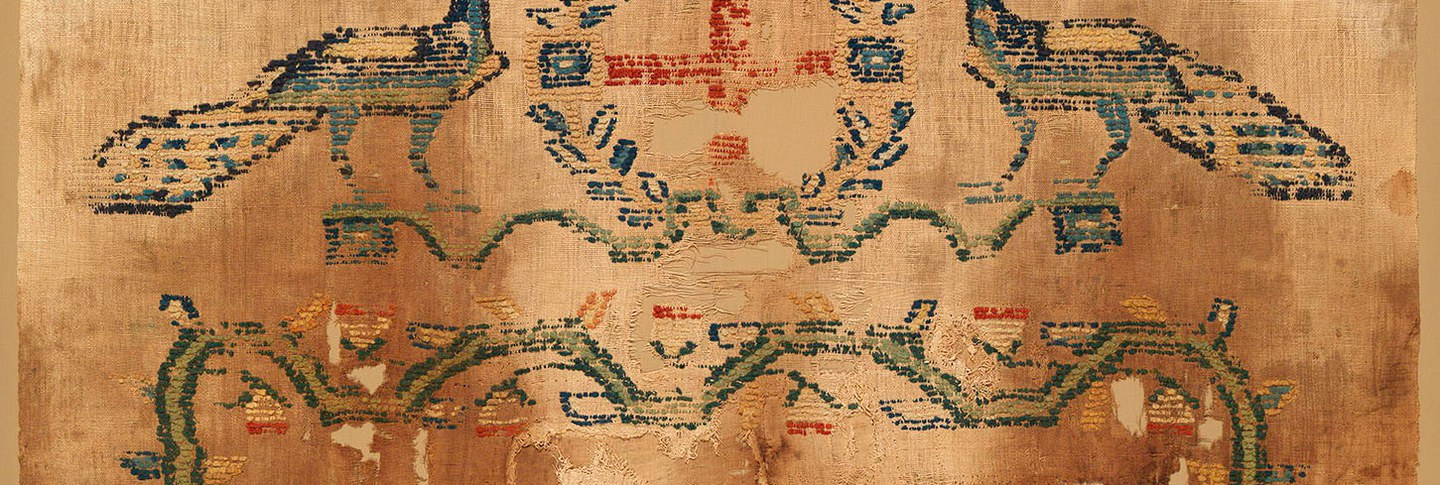

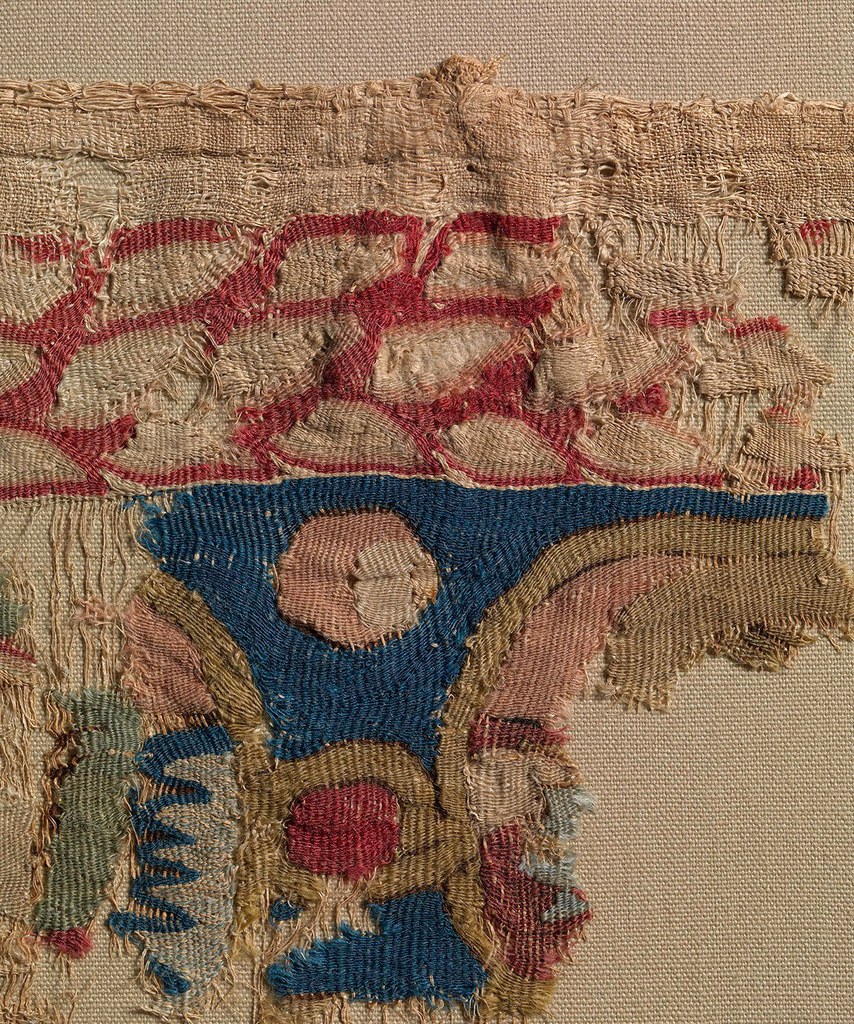

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has a remarkable weaving with a design woven in multicolored weft-loop pile in wool set against a plain weave ground in undyed linen (fig. 1). The textile’s deteriorated condition, with large parts oxidized and others completely missing, attests to heavy use over time. It also speaks to a probable secondary function as a burial shroud.Even though the outlines of the oxidized areas on the textile are not as pronounced as they are on other examples from the era, it is likely that the Peacock Hanging survived because it was used in a burial context. See Antwerp, Katoen Natie, KTN 515 (DM34), for an example of a textile with areas stained from body fluids that appear to outline the shape of a body. The upper quarter of the hanging is decorated with two confronted peacocks resting on a vine.The major design elements in the hanging measure as follows: right peacock: 27.5 × 40 cm; left peacock: 28 × 42 cm; horizontal branch on which the peacocks rest: 5 × 73 cm; wreath with cross: 30 × 36 cm; each roundel: approximately 23 × 23 cm; field with nine roundels: 71 × 74 cm. At center, a leafy wreath encloses a jeweled red cross. The remaining three-quarters of the hanging is filled with nine roundels, each bearing either a dolphin (or perhaps fish), a rosette, or a basket of flowers or fruit. The center roundel is surrounded by two of originally four small cruciform rosettes. The field of nine roundels is framed by a meandering stem from which leaves and blossoms grow. The layout of this design is unique, although the flowers, baskets, and dolphin or fish are familiar motifs that often appear in late antique textiles.

The hanging’s composition was woven in vivid colors. Subtle color variations within the design are noticeable, especially in the jeweled borders of the roundels. The border of the center roundel is beige, those adjacent to it are dark green, and those in the four corners are orange. This chromatic arrangement draws the viewer’s eye to the dark circles, which are arranged in the form of a cross. In this context, also noteworthy is the motif of the small cruciform rosette seen here, which has been identified on numerous furnishing textiles as well as other works of art.See, e.g., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 90.5.642, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/444121, and 12.182.45 (fig. 13); Vienna, MAK, inv. T 11981-1999, in P. Noever, ed., Verletzliche Beute: Spätantike und frühislamische Textilien aus Ägypten (Ostfildern-Ruit, 2005), 159–60; and Paris, Musée du Louvre, Department of Egyptian Antiquities, inv. AF 6113, in M.-H. Rutschowscaya, Coptic Fabrics (Paris, 1990), 56. See also M.-H. Rutschowscaya, Catalogue des bois de l’Égypte copte (Paris, 1986), 154, no. 538, for a wood lintel with a central motif that could be a variation of a cruciform rosette. See also the wooden panel at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.112.1, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/453633. The reiteration of the cross motif throughout the hanging supports the supposition that it was used in a Christian context.W. Clarysse and K. Geens, “Textiles and Architecture in Graeco-Roman and Byzantine Egypt,” in De Moor and Fluck, Clothing the House, 38–47, and B. Caseau, “Objects in Churches: The Testimony of Inventories,” in Objects in Context, Objects in Use: Material Spatiality in Late Antiquity, ed. L. Lavan, E. Swift, and T. Putzeys (Leiden, 2007), 551–80. Furthermore, its bold, easily readable decorative features create a sense of monumentality best suited for a large space, possibly a church or monastery.I wish to thank Brandie Ratliff for sharing her research on the Peacock Hanging with me. Ratliff presented a paper entitled “A First Look at MMA 90.5.808” at the Dumbarton Oaks Museum conference “Liminal Fabric: Furnishing Textiles in Byzantium and Early Islam,” Washington, DC, March 26–27, 2015, which closely relates to my paper entitled “Technical Analysis of a Late Antique Hanging at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” given at the same conference.

The layout of the design and certain technical features suggest that the textile survives nearly complete. Selvages on either side indicate an original width of 129 centimeters. The hanging in its current state measures 170.2 centimeters in height, with losses at the bottom making it difficult to determine the original height.

Along the upper edge, purple-colored wool wefts were embedded within the undyed plain-weave ground. Most of the wool weft here has deteriorated, and the bare linen warp threads leave the impression of an open weave (fig. 11).The area between the upper purple-colored weft and the top edge of the weaving measures between 5.2 and 5.9 centimeters. The purple-colored wool weft is a combination of two differently colored fibers spun together, blue and brown. To finish the weaving along the top edge, a linen thread was repeatedly wrapped around a group of three warps, tied, and carried, in this manner, across the entire width (fig. 12a–b). This technical feature has been identified as characteristic of the treatment of upper and lower edges of numerous late antique furnishing and clothing textiles.A. De Moor, ed., Koptisch textiel uit Vlaamse privé-verzamelingen (Zottegem, 1993), 96 and 143. It is conceivable that the now missing lower edge—where the weaver started the work—was also secured using this technique.The direction of the weft-loop pile confirms that the Peacock Hanging was woven from the bottom to the top edge. A warp fringe might once have existed along the bottom. When they survive, such elements provide significant technical details regarding the weaving process, but the fragility of these areas makes their survival rare. One complete example is the Hanging with Nikes Holding Bowl of Fruit in the Met (fig. 13).For additional images, see http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/446223.

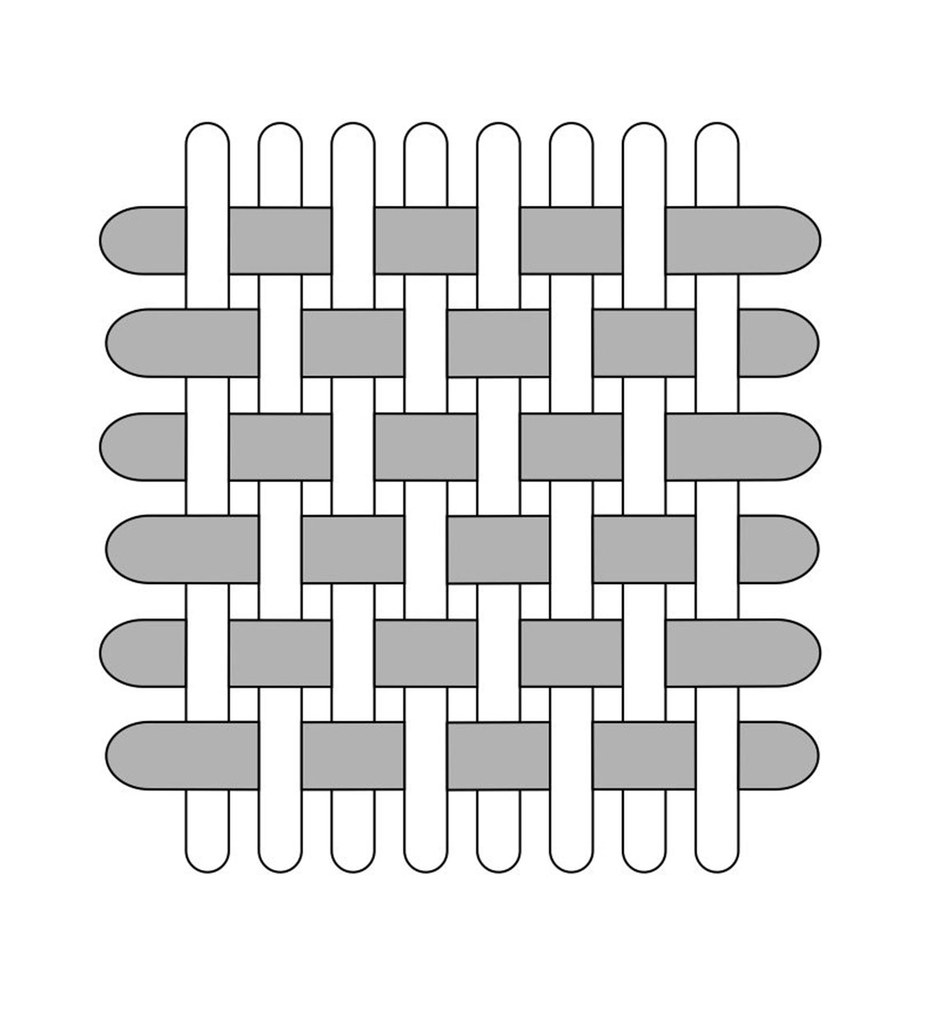

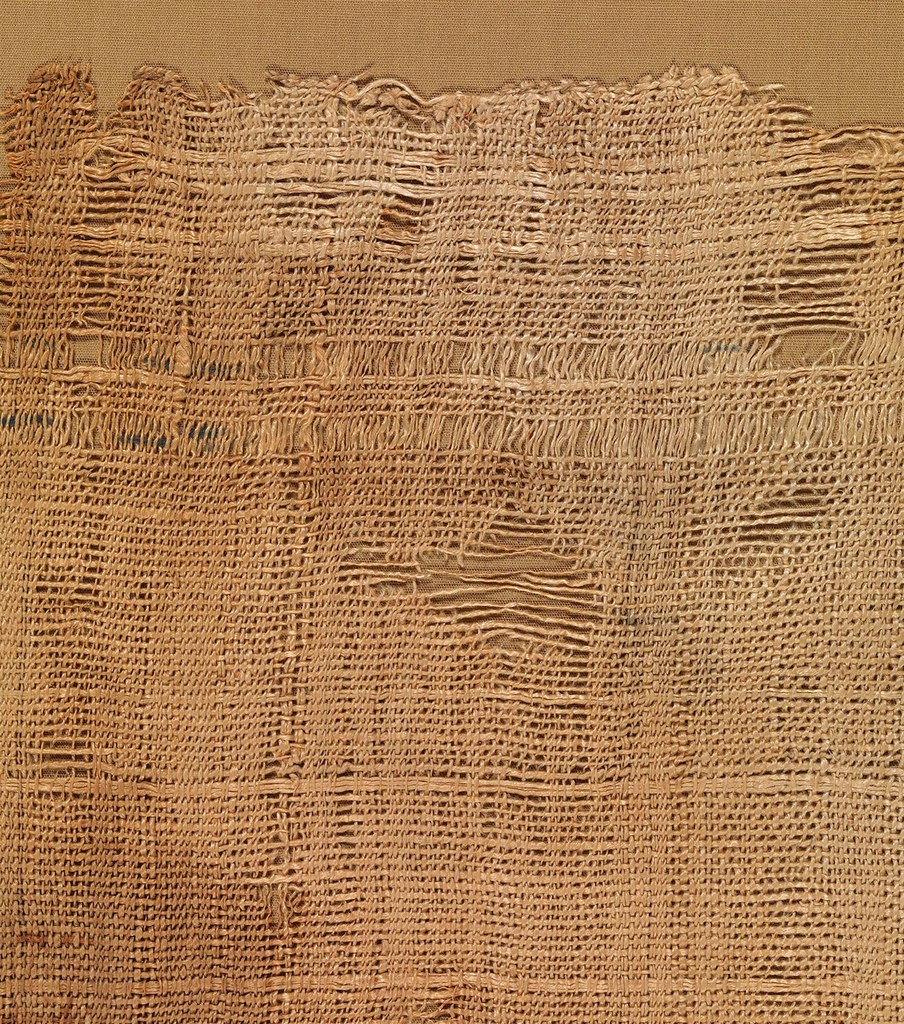

The ground of the Peacock Hanging is woven in plain weave (fig. 14a–b). The warp and weft are S-spun linen yarns, and possibly bleached.The direction in which a thread is spun, twisted, or plied is described by the diagonals of the letter “S” (\) for the clockwise direction and “Z” (/) for the counterclockwise direction, Burnham, Warp and Weft, 161. It is not known how the Egyptians bleached their cloth. Linen could have been washed and exposed to sunlight, or natron (a mineral deposit from the desert) could have been scrubbed into the fiber, which would then have been beaten, washed, and left in the sun to whiten. G. Vogelsang-Eastwood, “Textiles,” in Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology, ed. P. T. Nicholson and I. Shaw (New York, 2000), 280. The thread count of the warp is sixteen to twenty threads per centimeter and that of the weft is seven to eight per centimeter. Since the warp count is higher than the weft count, the plain-weave structure of the hanging becomes warp-predominant.For a description of plain weave with a predominant warp, see I. Emery, The Primary Structures of Fabrics: An Illustrated Classification (Washington, DC, 1980), 76. Discontinued paired warps with no particular sequence can occasionally be observed throughout the fabric. Although this may be a flaw introduced during weaving, it was more likely a deliberate manipulation of the warp setting to control the width of the fabric, a technical feature common in late antique textiles from Egypt. The warp thread count at the outermost edges was increased to twenty-eight per centimeter, which created a denser weave structure and thus provided reinforcement to these areas. The selvages themselves are composed of single warp ends.

Throughout the hanging, supplementary weft entries of two or three linen picks can be observed within the plain-weave shed, a feature known as self-bands.A shed is the opening that is created by raising or lowering a portion of the warp threads for a pick—that is, a weft thread—to be carried through. This kind of technical intervention appears commonly on late antique textiles, and was likely used to add further patterning to the plain-weave ground. The supplementary wefts were usually carried across the full width of the textile, creating dense lines that interrupt the regularity of the plain-weave ground. Close examination of the self-bands in the Peacock Hanging show that they are irregularly spaced, do not reach from selvage to selvage, and dominate on the right side of the weaving.Self-bands can be a helpful technical element in determining the placement of fragments within incomplete textiles. See Verhecken-Lammens, “Linen Furnishing Textiles,” 136. This suggests that these groupings of linen wefts did not have a decorative purpose, but rather were intended to create a counterbalance that compensated for the thickness of the wool weft. They show the weavers’ efforts not to disrupt the strict, horizontally built design.

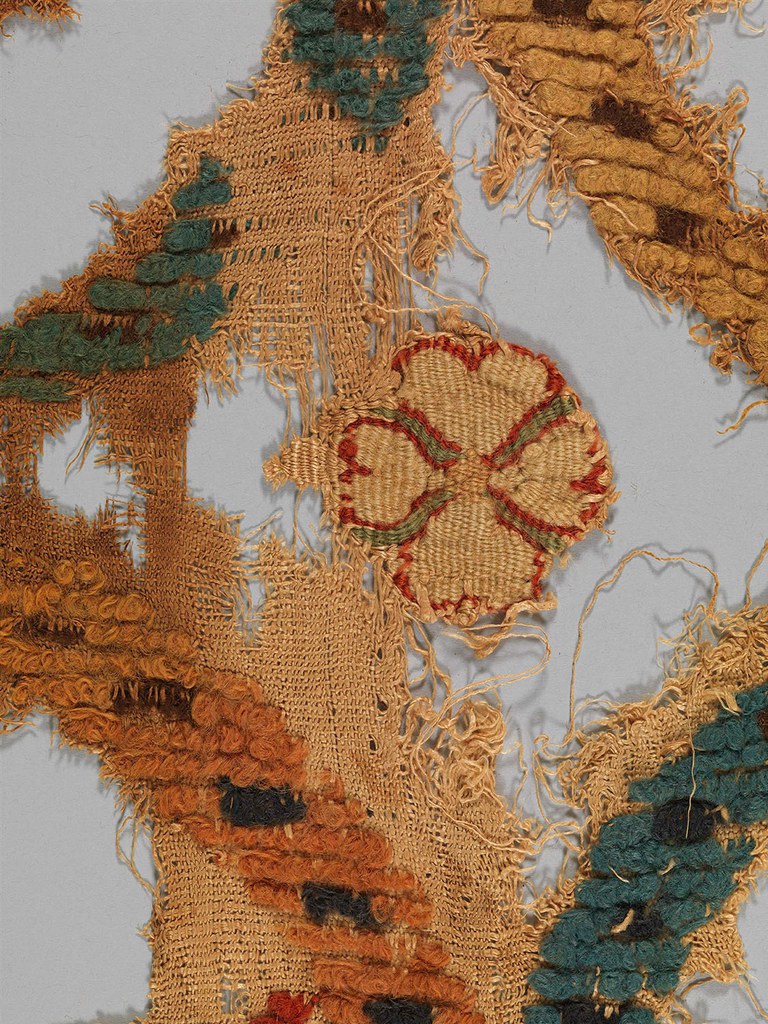

The design of the hanging, unlike the ground, was woven in weft-loop pile (fig. 15a–b).On the different types of loops identified on late antique textiles from Egypt, see ibid., 133–34. The supplementary wool weft, consisting of two S-spun yarns, was inserted into the same shed as the main linen weft. Between every third or fifth warp thread, the weft was pulled with a hook to the surface of the weaving to form a loop. A rod was placed through the loops to ensure the uniformity of their length. After completion of each pile row, the rod was removed.Ibid., 134. The completed row was then kept in place with three undyed linen wefts in plain weave, which created the undecorated, natural-colored ground. Given that there are only four to five loops per centimeter, with each loop approximately three to five millimeters in length, the final fabric is a rather coarse weave.

Two of what were originally four cruciform rosettes surround the center roundel.The surviving red rosette is 86.5 cm from the top and 74 cm from the right edge, measuring 5 × 6 cm. The surviving white rosette is 109 cm from the top and 73.5 cm from the left edge, measuring 5 × 5 cm. The rosettes are woven in tapestry weave; the warp is doubled or tripled with 7–8 threads/cm; the wool weft count is 24–28 threads/cm. Unlike the remainder of the design, these small rosettes were woven in tapestry weave, but they echo the rosettes rendered in weft-loop pile in shape and choice of color (fig. 16). Although it might seem unusual that the weaving combines these two techniques, there are other examples of such combinations (see, for example, fig. 3). While the reason for the contrasting techniques cannot be explained fully, we can conclude that it was intentional, because it required the weaver to adjust the warp setting in order for the warp to be covered with the colored wool weft—a distinctive feature of tapestry weave.For a discussion of tapestry weave, see Burnham, Warp and Weft, 144–49. Because designs woven in tapestry weave can usually be viewed from both sides, these rosettes are visible also on the back of the textile (fig. 17a–b).

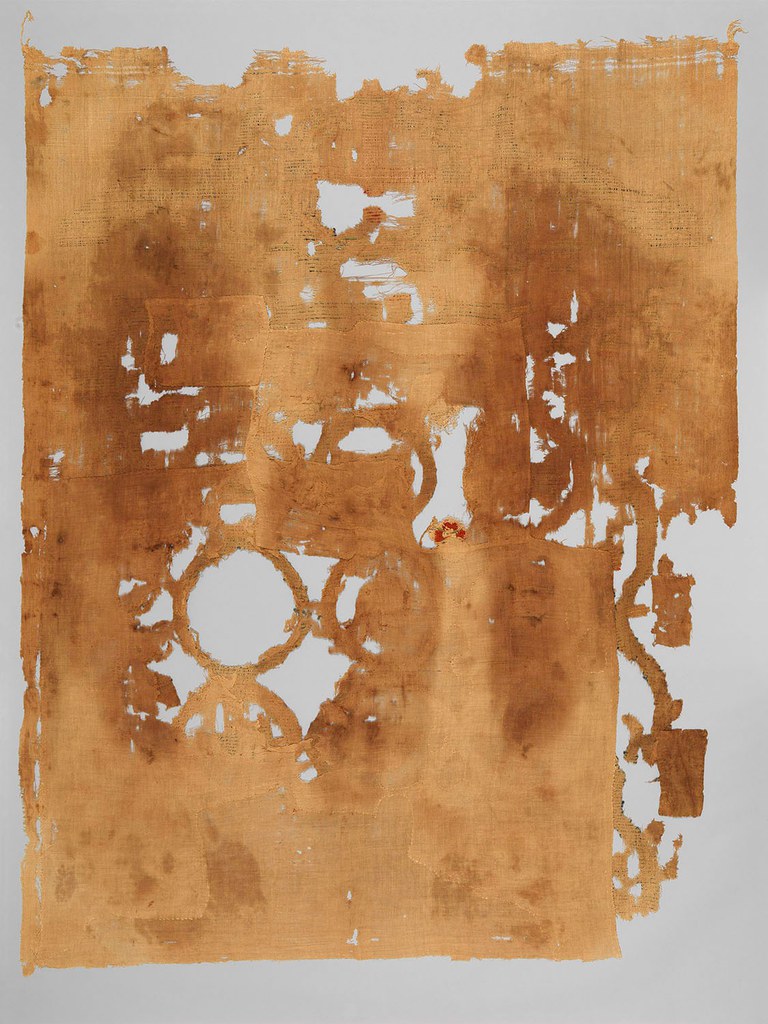

The Peacock Hanging entered the Met’s collection with an ancient repair sewn to its reverse (fig. 18). The repair, which consists of three separate fragments, measures 114.5 centimeters in height and 105 centimeters in width.The three fragments measure individually as follows: 89.5 × 105.5 cm, 40.7 × 46.4 cm, and 15.5 × 21.5 cm. During a conservation campaign in 2003, the ancient repair was removed from the hanging and the edges of the fragments were unfolded. During a conservation treatment in 2014–15, the ancient repair was positioned as closely as possible to its original location. The hanging was highlighted in the exhibition New Discoveries: Early Liturgical Textiles from Egypt, 200–400, curated by Helen Evans, Brandie Ratliff, and Kathrin Colburn, Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 23, 2015–September 5, 2016. Woven in balanced plain weave in linen, with a warp and weft thread count of fourteen per centimeter, both S-spun, the fragments were joined and then sewn to the hanging in running stitches and whipstitches.For a definition of balanced plain weave, see Emery, Primary Structures of Fabrics, 76. The linen sewing thread, S-spun, was used in some places as a single yarn, in others as a doubled yarn. A selvage is preserved along the left edge of the larger fragment, the lower edge of which was secured with tied warp threads. All other edges were folded to the back to prevent unraveling. In addition, two smaller fragments (also with their edges folded to the back) of coarser plain-weave structure (13 × 7 cm and 16.5 × 9 cm) once supported the far left edge of the hanging, where a large portion is now entirely missing. The repairs strengthened weakened areas to allow further use, a practice that was common at the time, and that testifies to the status of these weavings and their use over many years.Sometimes fragile areas were crudely mended, rewoven, or patched, as exemplified by two pieces in the Katoen Natie collection in Antwerp: A. De Moor, 3500 Years of Textile Art (Tielt, 2008), 142–43, inv. 519 (DM38), and 180–81, inv. 984. Fragile areas on the Dionysos Hanging in the collection of the Abegg-Stiftung in Riggisberg were carefully supported with linen patches: D. Willers and B. Niekamp, Der Dionysosbehang der Abegg-Stiftung (Riggisberg, 2015), 152 and figs. 97–98. In the case of the Hanging with Images of Abundance at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.9.3, fragile areas were rewoven; see http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/448227. Although some late antique textiles do show signs of repair, many of these interventions are small. In the case of the Peacock Hanging, a large-scale repair was possible only because the back of the textile mostly lacked any particular design features.

Scientific Analysis

Close studies of weaving techniques provide critical data about the production and use of late antique textiles, but their dating remains problematic. Most, like the Peacock Hanging, came to light during haphazard excavations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the absence of contextualizing information, scholars have traditionally depended on dimensions, composition, and certain iconographic criteria to date and categorize weavings. More recently, carbon-14 dating, mordant analysis, and dye analysis have been used to provide additional markers. A growing number of results have been incorporated into a database on radiocarbon-dated textiles established by the Abteilung Christliche Archäologie, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn.Textile-Dates, Abteilung Christliche Archäologie, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, http://www.textile-dates.uni-bonn.de. Having such information in one place can aid scholars in identifying groups of weavings with common characteristics from the same era. This in turn makes it possible to trace broader trends, such as the predominance of certain weaving techniques and iconographies over time.A. De Moor, M. Van Strydonck, and C. Verhecken-Lammens, “Radiocarbon Dating of a Particular Type of Coptic Woolen Tunics,” in Coptic Studies on the Threshold of a New Millennium: Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Coptic Studies, ed. M. Immerzeel and J. Van der Vliet (Leuven, 2004), 2:1425–42; M. Van Strydonck, A. De Moor, and D. Bénazeth, “C-14 Dating Compared to Art Historical Dating of Roman and Coptic Textiles from Egypt,” Radiocarbon 46 (2004): 231–44; J. Wouters, “Dye Analysis of Coptic Textiles,” in De Moor, Koptisch textiel, 53–64; M. Van Strydonck, “The Importance of Radiocarbon Dating of ‘Coptic’ Textiles,” in Fluck and Linscheid, Favourite Fabrics, 25–29.

Dye Analysis

To learn more about the history of the Peacock Hanging, Nobuko Shibayama, Research Scientist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, performed dye analysis on wool samples of various colors (table). Using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a photodiode array (PDA) detector, Shibayama identified three dye sources, all of which are known to have been used in the production of textiles in late antique Egypt.See also Schrenk, Textilien des Mittelmeerraumes, 479–81; J. Wouters, “Dye Analysis in a Broad Perspective: A Study of 3rd- to 10th-Century Coptic Textiles from Belgian Private Collections,” Dyes in History and Archaeology 13 (1995): 38–45; J. Wouters, I. Vanden Berghe, G. Richard, R. Breniaux, D. Cardon, “Dye Analyses of Selected Textiles from Three Roman Sites in the Eastern Desert of Egypt: A Hypothesis on the Dyeing Technology in Roman and Coptic Egypt,” Dyes in History and Archaeology 21 (2008): 1–16.

|

|

Color of sample |

Materials, other remarks |

Suggested dyes |

Detected main compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Red |

Wool |

Madder (probably Rubia tinctorum L.) |

Alizarin, purpurin, probably munjistin and pseudopurpurin |

|

2 |

Orange |

Wool |

Madder (probably Rubia tinctorum L.), weld (Reseda luteola L.) |

Luteolin 7-O-glucoside, luteolin, alizarin, purpurin, probably munjistin and pseudopurpurin |

|

3 |

Yellow |

Wool |

Weld (Reseda luteola L.) |

Luteolin 7-O-glucoside, luteolin |

|

4 |

Light green |

Wool |

Indigo dye (Isatis tinctoria L., or Indigofera sp.), weld (Reseda luteola L.) |

Luteolin 7-O-glucoside, luteolin, indigotin |

|

5 |

Green |

Wool |

Indigo dye (Isatis tinctoria L., or Indigofera sp.), weld (Reseda luteola L.) |

Luteolin 7-O-glucoside, luteolin, indigotin |

|

6 |

Blue |

Wool |

Indigo dye (Isatis tinctoria L., or Indigofera sp.) |

Indigotin |

|

7 |

Dark blue |

Wool |

Indigo dye (Isatis tinctoria L., or Indigofera sp.) |

Indigotin |

|

8 |

Purple (reddish purple fibers) |

Wool |

Madder (probably Rubia tinctorum L.) |

Alizarin, purpurin |

|

|

Purple (purplish blue fibers) |

Wool |

Indigo dye (Isatis tinctoria L., or Indigofera sp.), madder (probably Rubia tinctorum L.) |

Alizarin, purpurin, probably munjistin and pseudopurpurin, indigotin |

|

9 |

Beige |

Wool |

Unidentified, possibly undyed |

No characteristic colorant was detected |

|

10 |

Brown |

Wool; the fibers appear to be more brittle than those of other colored yarns |

Unidentified |

No characteristic colorant was detected |

Table. Summary of suggested dyes used for the wool weft in the Peacock Hanging. Table compiled by Nobuko Shibayama.

Among the dyes that could be identified are: a type of madder, most likely Rubia tinctorum L., for red; weld, Reseda luteola L., for yellow; and an indigotin-containing dye such as woad, Isatis tinctoria L., or indigo, Indigofera sp., for blue.C. Mouri and R. Laursen, “Identification of Anthraquinone Markers for Distinguishing Rubia Species in Madder-Dyed Textiles by HPLC,” Microchimica Acta 179 (2012): 105–13; A. Lucas, Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries, 4th ed. (London, 1926), 150–54. An analytical method to differentiate indigotin-containing dyes chemically has not been established—that is, woad or plants of the Indigofera species, a plant source for the blue dye, cannot be identified with certainty. However, since woad is a dye plant known to have been cultivated in Egypt during early Christian times, it has widely been suggested as the blue dye source in textiles from late antique Egypt. J. Wouters, “Red and Purple Dyes in Roman and ‘Coptic’ Egypt,” in De Moor and Fluck, Clothing the House, 182–85. In the analysis of the orange sample, weld and madder were detected, while the analysis of the green sample yielded a combination of an indigotin-containing dye and weld, a combination that was common in late antique Egypt. Shibayama remarked in her report that the sample from the brown wool, which was used in the design of the border of some of the roundels and other selected small details, was the most damaged of all, and no characteristic colorant was detected.Given the highly oxidized state of the fiber (possibly caused by pretreatment of the wool fiber with an iron salt as a mordant), it could have been dyed with a tannin dye. Since ellagic acid, a unit of hydrolysable tannins, was not detected, the source of the brown dye could be condensed tannins, for example, the bark of Acacia nilotica (Egyptian mimosa), which is reported to have been an important source of tannins in Egypt. See F. N. Hepper, Pharaoh’s Flowers: The Botanical Treasures of Tutankhamun (London, 1990), 22–23; D. Cardon, Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science (London, 2007), 462–65. Analysis of the purple yarn, which was used in the weaving of the peacocks, revealed two differently colored fibers spun together: purplish-blue fibers, which were dyed with an indigotin-containing dye and madder, and reddish-purple fibers, dyed with madder only.Shibayama commented that indigotin was not detected in the reddish-purple fibers, possibly due to the small sample size. Madder with an indigotin-containing dye such as woad was a common combination to achieve purple hues in late antiquity. The reddish purple may also have been achieved by using a madder dye with a mordant containing iron.

It is notable that such a rich color palette could be achieved with only three dyes used on their own, in combination, or in various concentrations. Colors can vary greatly depending on the mordants used during the treatment of the fibers before dyeing.R. Hofmann-de Keijzer and M. R. van Bommel, “Dyestuff Analysis of Two Textile Fragments from Late Antiquity,” Dyes in History and Archaeology 21 (2008): 19. At times, as in the present case, two differently colored fibers were spun together to achieve further hues; also, fibers were sometimes used in their natural state, such as for beige and brown hues.

Carbon-14 Dating

To aid in the dating of the hanging and in its repair, samples were taken for carbon-14 testing.Nobuko Shibayama coordinated the carbon-14 analysis, which was performed and evaluated by Christine Prior, Rafter Radiocarbon Laboratory, New Zealand. For a general discussion of carbon-14 dating, see C. Prior, “A Carbon-14 Primer,” HALI 174 (2012): 24–27. See also G. Bonani, “Radiocarbon Dating of Milligram Samples of Anatolian Kilims by Accelerator Mass Spectrometry,” in Anatolian Kilims and Radiocarbon Dating, ed. J. Rageth (Basel, 1999), 15–22; A. De Moor, M. Van Strydonck, C. Verhecken-Lammens. “Radiocarbon Dating of Two Sasanian Coats and Three Post-Sasanian Tapestries,” in Riding Costume in Egypt: Origin and Appearance, ed. C. Fluck and G. Vogelsang-Eastwood (Leiden, 2004), 181–87; De Moor and Fluck, Methods of Dating Ancient Textiles. The relatively large size and fragmentary state of the hanging allowed for non-obtrusive removal of samples from two different locations. (Sampling from more than one location creates a greater likelihood of accuracy in determining a calendar year than a single sampling does.One sample was removed from the plain-weave ground along the lower edge; the second sample was acquired by removing linen weft threads from the plain-weave ground in the right medallion containing a dolphin or fish (first row, far right). The removal of neither sample compromised the integrity of the hanging.) To investigate the date of the ancient repair, a sample was removed from it as well.The sample was removed from the largest of the fragments, and did not compromise the textile’s integrity.

The results of all three samples were compared to determine the calendar-year date range of the hanging and repair.Radiocarbon analysis cannot directly measure the date of manufacture of a textile. Instead, it measures the time of harvest of the plant that was used to make the fibers from which a textile was woven. However, since it is very unlikely that many years would pass between the harvesting of the flax and subsequent spinning of the yarn to produce a weaving, in almost every case the radiocarbon age of the plant fibers will indicate the time of manufacture of a textile. In the case of the hanging, since both samples are from the same weaving event, a comparison of their calendar age ranges indicates the most probable age of the hanging. The two calibrated age ranges overlap in a calendar range from 346 to 402 CE. The sample taken from the ancient repair produced a radiocarbon age relatively close to those dates, from 383 to 527 CE. This result indicates that the repair, made to reinforce weakened areas of the hanging, was woven at least a few decades after the hanging itself.

However, the analysis also shows that there is a smaller but not insignificant chance that the repair could have been manufactured either between 495 and 510 CE or between 520 and 527 CE. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that it might have been made as many as two hundred years after the hanging. Moreover, while the scientific results can assist us in the dating of the fabric used for the repair, it is impossible to establish with any certainty when the repair was sewn to the reverse of the hanging.

Textiles as Architectural Elements: Hanging Systems

One of the most interesting technical features of the Peacock Hanging can be found at the textile’s upper corners, where loops of plied linen cords were sewn to the face of the hanging (fig. 19a–b). The cords used to form these loops vary in make, suggesting that weavers might have used available threads rather than producing cords specifically for the hanging.The cord on the right is almost complete. It is about sixteen centimeters in length and has a diameter of approximately two millimeters. The cord was made of two threads, each consisting of four S-spun yarns plied in Z direction; the two threads are in turn plied in S direction. Of the cord from the left corner, only about six centimeters are preserved, with a diameter of about four millimeters. This cord was made of two threads, each consisting of five S-spun yarns plied in Z direction; the two threads are in turn plied in S direction. The ends of each cord were sewn to the face of the hanging with a linen yarn, S-spun. (Plied yarn is created from two or more single yarns spun in S direction or Z direction and then twisted together in the opposite direction. Depending on the number of single yarns, a 2-ply, 3-ply, etc. yarn is created.) Based on a comparison with other textiles that preserve signs of their installation systems, it is likely that four loops were originally sewn to the upper edge, spaced approximately forty-three centimeters apart. The loops attest to the practical systems used to hang textiles within architectural settings in late antiquity, a topic that has thus far not been systematically studied in the scholarly literature.H. Granger-Taylor, in D. Buckton, ed., Byzantium: Treasures of Byzantine Art and Culture from British Collections (London, 1994), 102–3, no. 112, observed different degrees of discoloration along the upper edges of a pair of curtains from the British Museum, London, EA 29771. She attributes this to the folding of the upper edges for installation. On this pair of curtains, see also E. D. Maguire, “Curtains at the Threshold: How They Hung and How They Performed,” in the present volume. S. Schrenk, “(Wall-)Hangings Depicted in Late Antique Works of Art? The Question of Function,” in De Moor and Fluck, Clothing the House, 153, mentions that until now evidence for hooks or holes on walls associated with the installation of textiles has been limited. She also stresses that evidence for hanging methods of weavings has only begun to be analyzed. P. Grossmann, “Late Antique Architecture in Egypt: Evidence of Textile Decoration,” in De Moor and Fluck, Clothing the House, 34, remarks that in the monastic cells at Kellia, goat horns have been found above prayer niches (oratoria) to which small curtains may have been attached to hide these areas when not in use for prayer. See also J. W. Stephenson, “Veiling the Late Roman House,” Textile History 45, no. 1 (2014): 18–21.

Evidence from complete textiles and surviving fragments of upper parts of weavings reveals much about the various mechanisms used to hang textiles within buildings. Some of these textiles retain their original means of hanging, or they feature details that hint at systems that were once in use, such as remnants of threads or even damage, such as holes.A fine example showing remnants of linen threads and small holes along the fragment’s upper edge is New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 90.5.611, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/444090. Instead of cords, as seen on the Peacock Hanging, sometimes strips of cloth were sewn into loops and stitched to the upper edge of the textile just far enough apart to avoid having it sag or wrinkle when it was hung by a rod or string that was passed through the loops and attached to hooks or nails extending from a wall or other architectural element.See the well-preserved finger-shaped curtain hooks above the narthex doors of Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, dated to the sixth century, illustrated in Maguire, “Curtains at the Threshold,” figs. 7a–b. This type of system kept the weaving taut and ensured that the hanging’s imagery was fully visible.

An almost-complete hanging in the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie in Besançon (inv. D.900.3, measuring 138 × 83 cm) preserves two of what were originally three tabs attached to its face.Y. Lintz and M. Coudert, eds., Antinoé: Momies, textiles, céramiques et autres antiques; Envois de l’État et dépôts du musée du Louvre de 1901 à nos jours (Paris, 2013), 256, no. 75. The tabs appear to be of rather crude construction, suggesting the possibility that at times this feature was intended to be hidden within the architectural framework. On another fragment of a hanging in the Met’s collection (fig. 20a), strips of cloth sewn into tabs have been identified on the back of the weaving.For additional images, see http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/444378. Two tabs are still preserved fifty-six centimeters apart from each other along the upper edge of the fragment, which is sixty-six centimeters wide. Interestingly, the strips were placed at an angle, probably to aid in distributing the weight of the hanging evenly and to anchor the tabs to the textile more securely (fig. 20b–c).For tabs of linen cloth sewn to the top edge of textile fragments, see also Stuttgart, Landesmuseum Württemberg, GT 3809, GT 3810, in C. Nauerth and N. Trentin, Die koptischen Textilien im Landesmuseum Württemberg (Stuttgart, 2014), 73–75); and Brussels, Musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire, Tx. 296, in J. Lafontaine-Dosogne, Textiles coptes des Musées royaux d’art et d’histoire (Brussels, 1988), figs. 15–16.

Sometimes the upper edges of hangings were folded around a fibrous material to strengthen it for the attachment of loops. This treatment can be seen on the Met’s Hanging with Nikes Holding Bowl of Fruit (fig. 13). Three loops, each constructed of long linen cords between 7.5 and thirteen centimeters, were stitched to the reinforced top edge, spaced 25.5 centimeters apart from each other (fig. 21).For further discussion, see J. L. Ball, “Rich Interiors: The Remnant of a Hanging from Late Antique Egypt in the Collection of Dumbarton Oaks,” in the present volume. A similar treatment appears on a fragment of a hanging in the collection of Katoen Natie; in this case the cloth was folded along the upper edge (which measures 104 centimeters) over a thick cord and secured with stitches. Six loops were attached to the reinforced upper edge, spaced twenty centimeters apart.Antwerp, Katoen Natie, KTN 1735: Verhecken-Lammens, “Linen Furnishing Textiles,” 142–43; Paetz gen. Schieck, in Fluck and Linscheid, Favourite Fabrics, 150.

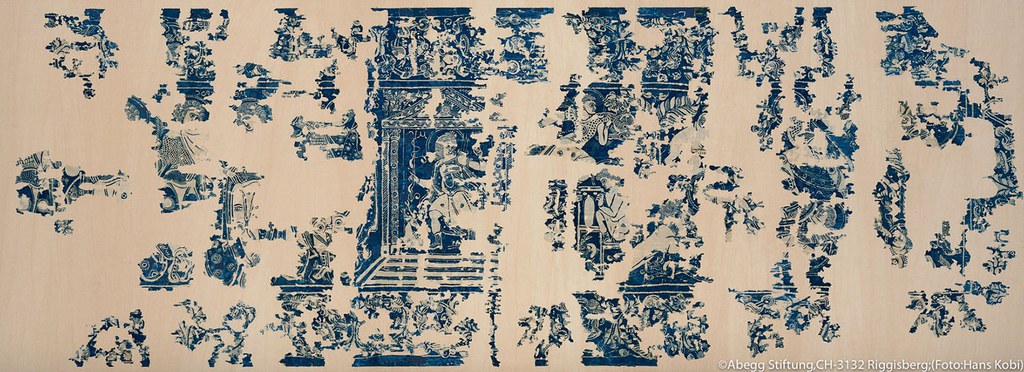

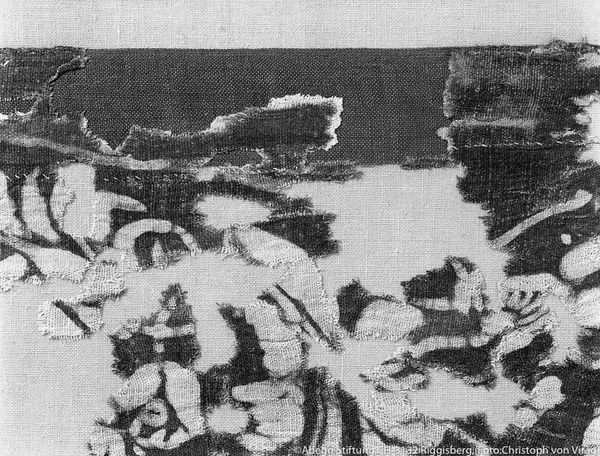

The significant weight of large textiles was a major factor in designing methods for installing them. A fragmentary wall hanging painted with scenes from the Old Testament now in the Abegg-Stiftung probably once featured fourteen cords along its upper edge (which measures 436 centimeters), spaced approximately fifteen centimeters apart (fig. 22a).M. Flury-Lemberg, “Zur restauratorischen Rückgewinnung des bemalten Behanges,” in Der bemalte Behang in der Abegg-Stiftung in Riggisberg: Eine alttestamentliche Bildfolge des 4. Jahrhunderts, ed. L. Kötzsche (Riggisberg, 2004), 24; Schrenk, Textilien des Mittelmeerraumes, 65–70, no. 15. Remarkably, five of those cords survive intact, rare evidence for the textile’s original hanging system (fig. 22b). To strengthen the edges for installation and for the attachment of the cords along the upper edge, a narrow piece of linen cloth was folded around all four edges and secured with stitches.

For similar reasons, the upper edges of hangings were also sometimes reinforced with cloth strips, as on the Abegg-Stiftung’s Artemis hanging. This piece, which measures six hundred centimeters across in its current montage, retains evidence of a strip of plain-weave linen cloth five centimeters in width secured along its top edge (fig. 23a–b).Schrenk, Textilien des Mittelmeerraumes, 82–88, no. 19. A hanging in the Landesmuseum Württemberg in Stuttgart preserves a comparable feature along its upper left corner, where a 2.5 centimeter-wide hem was stiffened to strengthen the top edge for installation.Stuttgart, Landesmuseum Württemberg, inv. 1984-103; Nauerth and Trentin, Koptischen Textilien, 14–17. I wish to thank Bettina Beisenkötter, Textile Conservator at the Landesmuseum Württemberg, for the technical analysis of the hanging.

Finally, I note an observation that Heinrich Swoboda made in his 1892 article on a late antique Egyptian hanging then in the collection of Theodor Graf.H. Swoboda, “Ein altchristlicher Kirchen-Vorhang aus Aegypten,” Römische Quartalschrift für christliche Altertumskunde und für Kirchengeschichte 6 (1892): 95–113, reconstruction on p. 105. An image of the hanging appears in Wulff and Volbach, Spätantike und koptische Stoffe, 12 and plate 47. The hanging entered the Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (inv. 4832) in 1905, but has been lost since 1945 (Kriegsverlust). At the time of Swoboda’s study, only the left half (measuring 371 × 140 cm) had survived.Wulff and Volbach, Spätantike und koptische Stoffe, 12, states the dimensions to be 371 × 162 cm, twenty two centimeters wider than those given by Swoboda. See Swoboda, “Altchristlicher Kirchen-Vorhang,” 96. Given its composition, however, the hanging must have been at least twice as wide. Swoboda observed some almost intact loops along its top edge, as well as remnants of loops at the outer edge of the lower quarter of the hanging. He suggested that when the hanging was in use, strings would have been placed through the loops to attach it along the top and side edges to surrounding architectural elements. This method kept the weaving taut, serving to prevent people from entering or seeing what lay beyond it. Over time, however, tension caused by the pulling of the strings must have weakened the fabric, resulting in localized damage along its edges—which suggests long-term placement and repeated use.Swoboda, “Altchristlicher Kirchen-Vorhang,” 109. I wish to thank Dr. Gabriele Mietke, Curator for Byzantine Art, Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Berlin, for her generosity in providing me with scans of glass plates of the lost hanging, which allowed me to examine it in more detail.

Context and Use

Artistic renderings give little sense of how such textiles hung in three-dimensional spaces, or how individuals or groups interacted with them. But depictions in contemporary mosaics and manuscripts can serve as valuable comparative material in the attempt to determine the methods used to hang textiles in architectural spaces. One such example is the fifth- to seventh-century floor mosaic from the synagogue at Beth Shean A now at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, which shows the Ark of the Covenant flanked by two menorahs and other ritual objects (fig. 24).See K. M. D. Dunbabin, Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World (New York, 1999), 190, and R. Rosenthal-Heginbottom, “The Curtain (Parochet) in Jewish and Samaritan Synagogues,” in De Moor and Fluck, Clothing the House, 155–69. Grossmann, “Late Antique Architecture in Egypt,” 33, points out that sometimes textiles were attached with metal rings to horizontal bars. I would like to suggest that these rings most likely would first have to be placed through the hanging system that was attached to the top edge of the textile, such as loops or tabs. This type of system is what we might see on the mosaic from the Israel Museum. At center, a textile is suspended from a rod that runs through loops along its upper edge. One can picture the Peacock Hanging suspended in a similar way, since the rod allowed the entire composition to be appreciated without many folds.

The floor mosaic from Beth Shean also suggests that weavings like the Peacock Hanging were meant to be primarily viewed frontally. As Brandie Ratliff has argued, this hanging may have been set up across an opening, perhaps a small niche, either to hide a storage space or to protect a revered object (fig. 25).Niches are common features of late antique churches in Egypt. See, for example, well-preserved niches near the Birth House of the Hathor Temple, late fifth–sixth century, Dandarah, Egypt: J. McKenzie, The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, c. 300 BC to AD 700 (New Haven, CT, 2007), 282–83. Given that the design was woven in the loop-pile technique and is therefore visible only on the face of the textile, it is this side that was most likely privileged when it was installed (fig. 17a–b). Furthermore, areas of loss and wear along the lower half indicate repeated handling, and the missing lower-left edge, which was repaired in ancient times to allow further use, suggests that the hanging might frequently have been pulled toward the right side to expose what was concealed behind it.

Three-dimensional objects also invite us to imagine the use of these weavings in situ, and deserve further scrutiny for evidence of hanging systems. A marble ciborium from Italy in the collection of the Met, dating to about 1150, helps us to envision how furnishing textiles may have been hung in sacred spaces (fig. 26a).For additional images, see http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/463315. Although the ciborium is of later date, its form recalls the shrines depicted in late antique mosaics, with a canopy set above columns. The top edge of the interior-facing surface of each capital shows the open end of a channel into which molten lead was poured to surround and fix internal pins that connected the various elements of the structure (fig. 26b).I wish to thank Carolyn Riccardelli, Conservator, Department of Objects Conservation, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, for her clarification on the construction of the ciborium, which she examined in a dismantled state. Riccardelli determined that the ciborium would originally have been assembled with the aid of iron pins that connected the various stone elements of the structure. These pins fit into pairs of holes drilled into the center of each column and were held in place with lime mortar. In certain strategic locations where a fast-setting joint was required, channels were carved into the stone, directed toward the central pinhole, and molten lead was poured in to fill the space around the iron pin. The lead then solidified and instantly strengthened the structure by locking the pin in place. The holes visible on the ciborium’s capitals are the openings of such pouring channels. Channel openings can be observed in other locations of the ciborium where critical structural support was required, such as the column bases. I thank Peter Zeray, Senior Photographer, Imaging Studio, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, for taking detailed photographs of the ciborium. It is entirely possible that these channels served a second function following the assembly of the ciborium, as openings to insert rods for the installation of textiles.

Conclusion

The features and techniques discussed here help us envision late antique furnishing textiles from Egypt in their original environments, both material and cultural. Through detailed analyses, we gain informed knowledge of the Peacock Hanging: its artistry, purpose, and weave structure, as well as which dyes might have been used, when it was woven, and what kind of system was employed to hang it. These findings allow us to hypothesize how and where the textile was hung. While architectural evidence remains scarce and the information preserved in and on surviving late antique textiles is limited, every new clue brings us closer to answering our questions, and the excitement of discovery compels us to keep asking them.

During my research, valuable advice was offered by the following colleagues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Helen C. Evans, Mary and Michael Jaharis Curator of Byzantine Art, Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters, and Nobuko Shibayama, Research Scientist, Department of Scientific Research. I am also grateful to Janina Poskrobko, Conservator in Charge, Department of Textile Conservation, for her support. In addition, I would like to acknowledge Bruce J. Schwarz, Senior Photographer, Imaging Department, who undertook the photography of the textiles from the Met reproduced here, and in particular his work on the Peacock Hanging. I wish to extend my gratitude to Kathrin Mälck, textile conservator, Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Berlin; to Bettina Niekamp, Head of the Textile Conservation Workshop, Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg; to Brandie Ratliff, Director, Mary Jaharis Center for Byzantine Art and Culture at Hellenic College Holy Cross; to Melody Lawrence for editorial input; to Gudrun Bühl for her enthusiasm and engaging conversations on the topic; and in particular to Elizabeth Dospěl Williams for her continuous guidance in the course of preparing this essay for publication.

Cite this Essay

Kathrin Colburn, “Loops, Tabs, and Reinforced Edges: Evidence for Textiles as Architectural Elements,” in Catalogue of the Textiles in the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection, ed. Gudrun Bühl and Elizabeth Dospěl Williams (Washington, DC, 2019), https://www.doaks.org/resources/textiles/essays/colburn.